For as long as we have been human we have looked for some way of telling when we are being told the truth. We tried dunking witches, only to find that buoyancy is not connected to the supernatural. We tried torture, but discovered that people will eventually say just about anything to make it stop. We experimented with scopolamine and sodium pentathol, to learn that ‘truth serums’ do little more than make their targets susceptible to suggestion. And we’re still trying – with scientists pushing MRI scans and ECGs alongside AI as a ‘brain fingerprinting’ technique. The jury is out as to whether the latest ideas will prove any more reliable than those that went before.

It was investigating brain fingerprinting that prompted Amit Katwala, a senior contributor to WIRED, to write Tremors in the Blood – named for the 1730 quote from the novelist and spy Daniel Defoe, who believed guilt always caused such a tremble. It is a shame we have to wait until the ‘Coda’ to learn that it was the modern search for an infallible truth machine that inspired Katwala, as what makes up the rest of the book is a thrilling, page-turning near-novelisation of the development of what we now know as the polygraph.

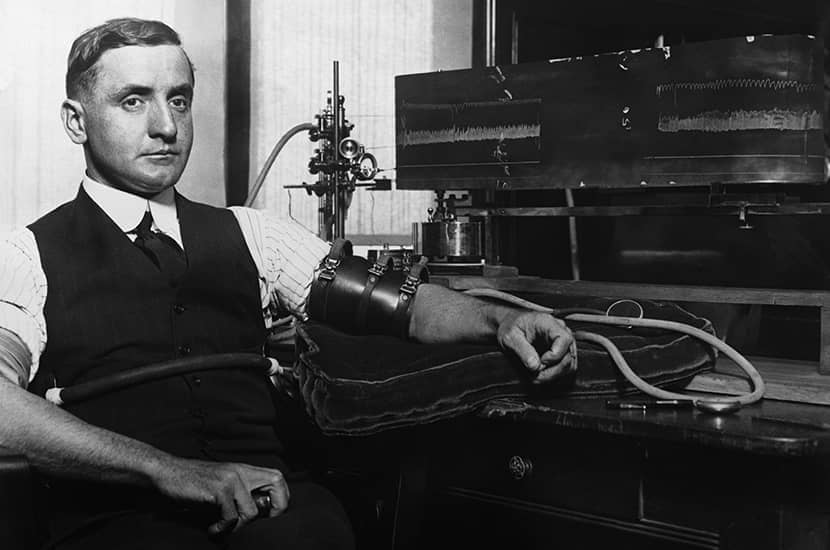

We begin in early 20th-century America, first in Berkeley, California, with August Vollmer, the man credited as the father of modern American policing, and observe the efforts of an uneducated boy made good to bring scientific method to a police force more used to dispensing justice by the ‘third degree’ (administered usually by beatings to the stomach). We are then taken to Chicago, following two of Vollmer’s protégés as they invent and ‘perfect’ what is initially named the ‘cardio-pneumo-psychograph’. It is a tale of friendship, romance, rivalry and murder as we witness the early polygraph’s use in two separate capital cases – with drastic results in each.

Those looking for a scientific rationale or debunking of the polygraph will be disappointed: this is not that book. We see doubts emerge for various inventors, and the author stresses that the technology – which is not admissible in court – does not work; but this is largely told as a matter of faith. Tremors in the Blood is not a work of popular science. Instead, Katwala’s meticulous archival research, centred around two high-profile US murder cases – those of Henry Wilkens and Joseph Rappaport – is worthy of any thriller. Omniscient third-person narration keeps the pace flowing, if at the risk of irritating pedants (we occasionally get the inner thoughts of people seconds before their death). This is a book begging to be optioned by Netflix or some other studio and would be a movie well worth watching.

Yet a niggling frustration remains. By the book’s end in the 1930s, our group of inventors had become largely disillusioned with the polygraph’s potential. We are left with only hints of what has happened since, though some may be aware of it. Polygraphs are routinely used today across huge swathes of life – in tests by intelligence and law enforcement agencies, in parole hearings, by the military and often by the US police, despite their inadmissibility in court – and we should consider the harm wreaked by Jeremy Kyle and his ilk on live television. How much worse that might be with a next-generation ‘lie detector’ of the sort Katwala describes in his ‘Coda’ – one that scans the brain and uses AI. To a layman, those words alone are enough to give an aura of infallibility to an entirely unproven technology.

Clearly this concern was Katwala’s motivation for writing the book; but it is hard not to wish he had combined his obvious narrative gift with a discussion of the consequences of the events he describes, and of why the technology didn’t work then and might not work now. Nevertheless, Tremors in the Blood will make us just as engrossed by the two murder cases he focuses on as news-parer readers were at the time – and leave us similarly wondering how, exactly, we might ever know whether someone is telling the truth.

Comments