Where are all the father-in-law jokes? You won’t find them, because fathers-in-law are not fair game in the way middle-aged women are. There is no male ‘Karen’. Men are not mocked as wizards, but we are witches. Victoria Smith has subtitled her timely book ‘The Demonisation of Middle-aged Women’, and if you are one of them you will know that is no exaggeration. Witches, crones, hags, scolds, evil mothers-in-law – up here in middle age, we are used to male scorn. But Smith has a different target: ‘I do not wish merely to present the myriad ways in which older women are belittled, undermined or misrepresented.’ We know all that, it’s obvious: ‘Ageist misogyny has always existed. What I think is different now, and what makes it more intractable, is that it frequently masquerades as feminism.’

These are dark days to be a woman. Yes, we’ve had #MeToo, writes Smith, but we’ve also had Jimmy Savile and Rotherham and Operation Yewtree. We have incels and rape porn and the woman-hating Metropolitan Police; and prosecutions for rape are now so rare that the crime can be done with actual impunity. We are living in misogynistic times. But compounding the problem is the fact that younger women seem to have fallen in with this.

Smith understands why they should dismiss their elders’ experiences: they don’t want to accept that they will eventually be them. No teenager pictures herself as middle-aged. This is a fundamental truth, even without the current cult of gender identity politics, where using the word ‘woman’ is biologically essentialist, and where younger women think that distancing themselves from their bodies will save them from ageing, or being thought phobic or privileged. How much could women have if they all acted as a sex, not as a generation. Intergenerational discord ‘interrupts the passing down of knowledge’. This was relevant, for example, in the overturning of Roe vs Wade in the US, Smith says:

Though many factors led to US women losing constitutional protection of their right to an abortion, they were not helped by the belief among younger feminists that to prioritise abortion rights at all smacked of anti-intersectional, biologically essentialist second-waverism.

In 2020, a tweet compared Covid-19 to feminism because both have ‘a problematic second wave’. It went viral.

Surveys show that two-thirds of young women identify as feminists. But what kind of feminists? The ones who prefer to talk of ‘menstruators’ and ‘uterus-havers’? The ones who think campaigning for single-sex spaces is exclusionary? (It is – of men.) Smith writes:

I can, however, think of plenty of feminist things I could have said as a teen or as a young woman which a young woman might not find it safe to say now for fear of being called phobic or bigoted. The space has been cleared for young women to identify as feminists because the women who identify with what ‘feminist’ used to mean now get called far worse names.

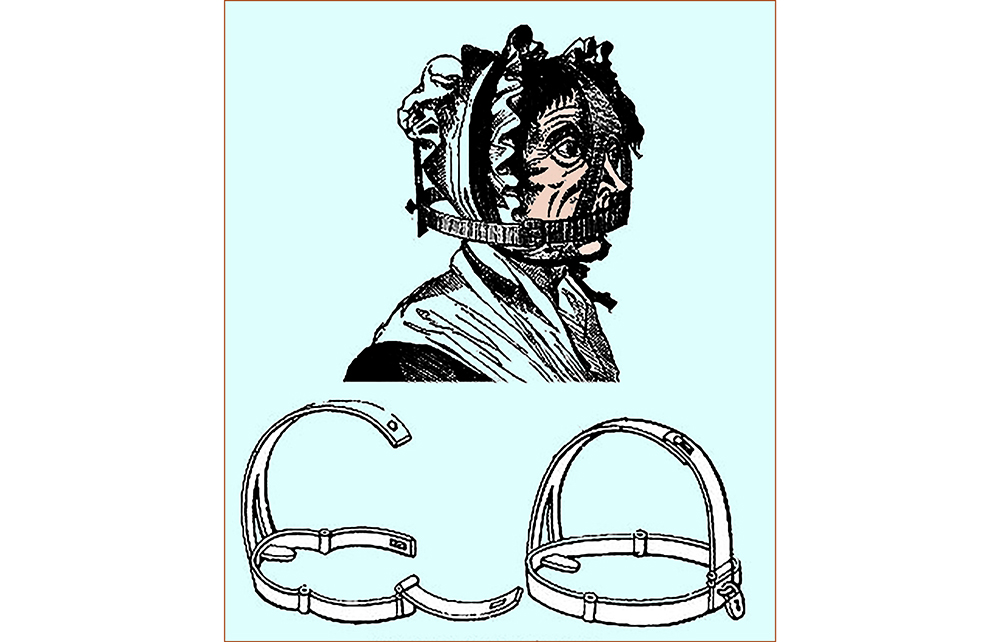

Transphobe. Bigot. Terf. Karen. Those are some of the names. Defend yourself, and you condemn yourself. As the Dutch theologian Martin Delrio wrote in his 1599 Disquisitionum Magicarum Libri Sex: ‘It is evidence of witchcraft to defend witches.’ This name-calling stems from what Smith terms the ‘new dawn’ tactic: older women have to be wrong and obsolescent because the next generation has to replace them, not join them. They don’t realise yet that every generation of women believes that – and still here we are, in a society where one in four domestic murders is of women over 60, and when older women are more likely to be ‘overkilled’ (a horrific word, meaning they suffer five or more injuries beyond what would have been needed to kill them).

That is the extreme. But to be a middle-aged woman is to have experienced decades of living in a body with the physical changes that periods, menopause and perhaps pregnancy and child-rearing bring. You can’t reach middle age without realising what being a woman entails. It means you do the care, and get penalised for it because it is unpaid work. It means unfairness and compromise. And it means understanding that men receive better pay, jobs and medical care, partly because of the reality of female biology. (Women are routinely excluded from medical research, due to their tricky menstrual cycles.)

It also means realising that older women don’t have the time to mess around. And it is this that threatens. Women as organisers are seen as menacing, and the ones who organise best are middle-aged, because life has taught them that they need to – even when they get it from all sides, and no one wants to listen to them in the first place. ‘Are we all mumsy milk cows, waffling on about our offspring’s flute class? Or are we al Qaeda?’, a middle-aged Mumsnetter asks.

Hags is rich and complex and witty and cleverer than I am. (You’d never get a male reviewer saying that.) I hope it won’t be read only in an echo chamber, by the women who are, as Smith was once called to her delight, ‘a batshit Mumsnet thread made flesh’. I hope it will also be read by young women who think me and the author terrible Terfs and bigots for believing in single-sex spaces; by young anyones; by the middle-aged and the elderly; by any man born of a mother; and by all those who agree with Smith when she writes: ‘I am not frightened of change. I am frightened of things staying the same.’

Comments