It’s really hard to imagine now a world before 24-hour news, continually and constantly accessible in a never-ending stream of on-the-spot, up-to-the-minute reports. What, then, would it be like to have no news summaries on the quarter-hour, no ‘live’ bulletins, no way of knowing what’s going on at this very moment in Kathmandu, Kabul or Khartoum? In his new three-part series for the World Service, War and Words (Sundays), Jonathan Dimbleby looks back to the late 1920s, when the fledgling BBC was not allowed to broadcast any news item until it had first appeared in print. Newspapers reigned supreme when it came to reliable and up-to-date reportage. The Corporation had no specialist news team, no foreign correspondents, no ‘embedded’ reporters in war zones (the Spanish Civil War changed all that). It relied for its copy on independent news-gathering agencies such as Reuters and the Press Association and, at the end of every bulletin, the BBC announcer had to state that the information just broadcast was the copyright of Reuters, etc.

American radio was way ahead of Auntie in realising the potential of news to capture the attention and hold on to audiences, and also of radio to provide something print never could: eyewitness accounts of events as they happen (although at first these news reports could not be ‘live’ because the technology was not yet capable of broadcasting away from the studio). We heard an extraordinary clip from a Chicago radio station, ‘the prairie farmer station’, dated 6 May 1937.

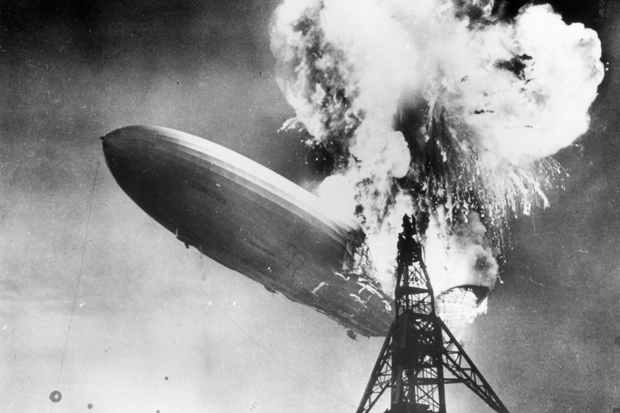

A reporter, Herbert Morrison, had been sent out with an engineer (who ‘cut’ the recording for later broadcast) to Lakehurst, New Jersey, to watch the arrival of the first airship of the season to cross the Atlantic. A routine assignment, thought Morrison. The journey had been done many times. But on this occasion the airship was the Hindenburg and after a few minutes of tedious comments about the massive silver-grey balloon appearing in an equally grey sky, Morrison suddenly screams, ‘It’s burst into flames.’

If you thought our own times are prone to a level of emotional expression never before heard or seen, this clip might surprise you. Morrison just falls apart on air. ‘It’s falling and crashing,’ he continues. ‘It’s smoke and flames now… Ahhh. Ohhh. It’s …it’s …I can’t talk, ladies and gentlemen. I’m sorry. Honestly,’ he gulps. ‘I can hardly breathe…’

In contrast to the visceral drama of that moment, and the amateurish recording, The Inquiry, also on the World Service (Tuesday), gave us another kind of radio experience: heavily manicured, complete with atmosphere-building background music and a rigorous four-part format. The subject under scrutiny was ‘Should Anyone Ever Talk to IS?’ so I kept on listening despite the slightly irritating slickness of the presentation (interestingly, the programme credits, unusually, list not just a producer but an editor also).

The presenter Helena Merriman talked to four experts: Jonathan Powell, the former adviser to Tony Blair and chief negotiator in Northern Ireland; Qais Qasim, an Iraqi journalist who still lives in Baghdad, in spite of his family being injured in a suicide attack; Mina al-Oraibi, the assistant editor of a London-based Arabic newspaper who has family living in IS-occupied Mosul; and Michael Semple, who has worked in Afghanistan for more than two decades and is known for his fluent Dari, long beard and habit of wearing the traditional garb of a Pashtun leader.

Powell said the question of whether to talk to terrorists or not could only depend on whether the group has political support, and if it does then you have no choice but to talk. This applied in Northern Ireland, he said, because the IRA could rely on one third of the Catholic vote. To talk might be ‘distasteful’, he said, but it was ‘inevitable’. But does IS have political support in those areas where it has taken control? That’s not so easy to find out.

Only Semple was given the advantage of being allowed to speak without any intrusive music, which gave his words an authority because they appeared unmediated and straight from the heart. He warned that his experience has taught him we are ‘in a long game here’, which requires ‘a different kind of conversation’. There is no way that politicians or diplomats could speak to IS in any meaningful way. But it might well be possible to have some kind of dialogue, a conversation of sorts, if the focus is on humanitarian issues rather than military or political outcomes.

He knows from his years in Afghanistan that this can work. Talks were begun with businessmen and traders, those who were trying to carry on as normal in spite of the violence. There were surprising outcomes. No great peace settlement was achieved but instead an environment that was ‘somewhat less dangerous’ for civilians, in which fewer innocent bystanders were killed and injured. A mass vaccination programme for children was implemented against polio. There was ‘a very significant change in behaviour’, Semple said, ‘but because it was about avoiding something it does not make the headlines’, it slips out of the news.

Comments