It is 3 a.m. in the Yemeni capital, Sana’a, and the Horse Shoe nightclub is a tableau to inflame the Jihadi heart with rage. To thumping music, Yemeni prostitutes cavort with fat, thuggish-looking local men. The tables are dotted with bottles of single malt costing $500 each (almost a year’s wages for the average Yemeni).

The hotel which houses the Horse Shoe, the Mövenpick, is assumed to be one of al-Qa’eda’s main targets, after the British and US embassies just across the road.Visiting journalists usually ask for rooms at the back, just in case a truck bomb makes it past the Yemeni army machine-gun emplacements at the entrance.

Still, no one — neither the famously charming and hospitable Yemenis, nor Sana’a’s flinty expat population — seems particularly anxious about an al-Qa’eda attack. That is partly because of the checkpoints ringing the capital and the presence of a secret policeman on every street corner. It is also that the Jihadis are not viewed as either very numerous or very competent. The success of the pants-bomber, Umar Farouk Abdulmuttalab, in only setting fire to his own crotch is seen as reassuringly symbolic.

Yet, it would be a mistake to underestimate al-Qa’eda in Yemen. Since unifying with the Saudi branch last year, it has behaved less like a small, national franchise and more like an international hub. A Yemeni regional governor says Saudi and Egyptian volunteers have been steadily arriving, some battle-hardened fighters squeezed out of Pakistan and Afghanistan.

The pants plot did, after all, cause a crisis in the US government and probably years of misery ahead for air travellers. Al-Qa’eda, if you believe its own statement on the matter, sees it as a success from that point of view. There may be a next time — the attempt to bring down Northwest Airlines Flight 253 on Christmas Day is evidence that al-Qa’eda is running an active research programme, constantly looking at ways to get dangerous materials through the airport security scanners.

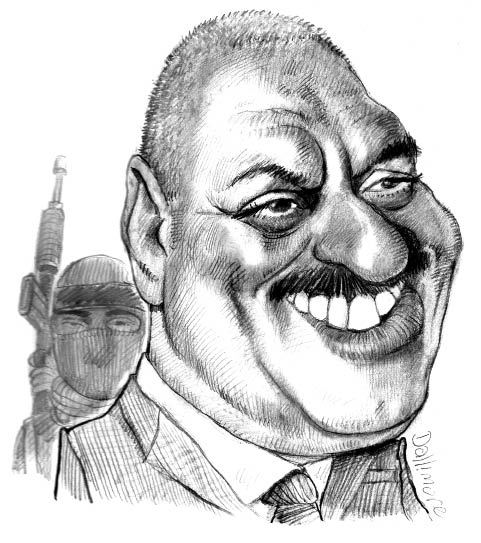

So the US government has told the Yemenis it is time to get tough with al-Qa’eda. They seem willing to comply, especially with international money on the table. But the government of President Ali Abdullah Saleh has some questions to answer about how — up until now — al-Qa’eda was apparently able to flourish so happily in Yemen.

‘It is a very complicated relationship [between al-Qa’eda and the Yemeni government]’, said Ali Saif Hassan, an independent political activist in Sana’a. ‘They have a history of working together and now they have to be separated. But it is like the operation to separate Siamese twins — it won’t be so easy.’ Specifically, the Yemeni government is said to have made a corrupt little deal with al-Qa’eda: they would be left alone as long as they exported their violence outside the country and weren’t too active in Yemen.

There are also allegations — never proved — that elements in the Yemeni military and security services provided safe houses and passports to al-Qa’eda operatives — again, as long as all this was for attacks, say, in Iraq.

The government always perceived the main threat to it to be the Houthi rebels in the north. There are persistent and credible claims — backed up, off-the-record of course, by UN officials — that Sunni al-Qa’eda fighters have fought the Shia Houthis on the government’s behalf.

Officials strenuously deny that. But tribes adhering to a Sunni Jihadist ideology not so far from al-Qa’eda’s have certainly been extensively used in the struggle with the Shia rebels. This is why although the number of al-Qa’eda members in Yemen is estimated only in the hundreds, there are said to be thousands of al-Qa’eda supporters. That last figure was given to me by the Yemeni foreign minister and is undoubtedly a vast underestimate.

I asked to meet a sheikh from one of the government-supporting tribes. We spoke sitting cross-legged on the floor in a house in Sana’a’s old city. The men were all in white robes, each with a djambia, the traditional Yemeni curved knife, stuck into a sash across the belly. The younger relatives and I chewed khat leaves, the mild narcotic beloved by almost all Yemenis. It was a bit like a mouthful of hedge at first, but quite effective in getting the conversation to flow.

Sheikh Arfej Bin Hadhban was from the mighty Bakil tribal coalition, who are not Sunni, but Shias of the Zaidi sect, just like the Houthis. In fact, most Bakil are fighting with, not against, the Houthi rebels. Confusingly, this particular sheikh had chosen to side with the government, in a war now in the sixth round of fighting and which seems to defy explanation even to Yemenis themselves. Just one odd fact of this conflict, for instance, is that the head of the government commission charged with negotiating peace is also reputed to be the north’s biggest arms dealer, selling to both sides.

The sheikh was, however, certain that one thing would end the squabbling between the pro-government tribes and the northern rebels, the Houthis, even bringing the southern separatists on board. ‘If there is an American intervention, the tribes would unite behind al-Qa’eda. What was a tiny movement would become a broad one. We are all Muslims. This would bring us closer together.’

Far better, said the sheikh, to let Yemenis battle al-Qa’eda’s ‘odious acts and devilish whims’ on their own. If American troops came to Yemen, the whole nation would ‘slide into a dark tunnel, like what happened in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iraq’.

The White House gets this. Wary of multiplying support for al-Qa’eda in Yemen many times over, President Obama said at the weekend that he would not be sending troops. With the neocons out of power in Washington, al-Qa’eda have lost their fellow ideologues of the ‘clash of civilisations’. Obama is not going to give them the war they seek.

Instead, to deal with al-Qa’eda, the outside world must rely on the Yemeni government. My Yemeni friend swore as we drove past the vast new mosque that dominates the approaches to Sana’a and which has been modestly named by President Saleh after himself. Able to hold 44,000 worshippers, the Saleh Mosque, or ‘Vanity Mosque’ as my friend calls it, is vastly out of scale with the hodge-podge charm of the capital city it overlooks. ‘This is the poorest country in the Middle East. We need schools and hospitals and he spends $60 million on this,’ said my friend. ‘He awarded all the contracts to his relatives and he got the money from businessmen, calling it donations, but really it was blackmail.’

Saleh’s foreign minister this week made a straight plea for cash to be handed over in large amounts at the London conference, saying terrorism and lack of development in Yemen were linked. But ordinary Yemenis wonder just how much of the millions the country will actually get will be lost to corruption.

From London and Washington’s point of view, the President does seem finally ready to do what is required about al-Qa’eda. It may be wrong to suppose — as is often said about Yemen — that the government is chronically weak and capable of doing little beyond the capital. ‘The Yemeni government has not yet started its real war against al-Qa’eda,’ said the independent political activist Ali Saif Hassan. ‘The government has a very powerful and strong machine. If they run this machine in their war against al-Qa’eda, as we saw it running in the last presidential election in 2006, they will achieve results. But the question is what will it take for Yemen to run that machine? That will be answered in the London conference.’

Even before the Christmas Day airline plot, Yemen had started to move against al-Qa’eda camps. On Christmas Eve, 14 fighters, including a local commander, were killed in a bombing raid. But al-Qa’eda had set up shop in an ordinary hill village, Maajala, and it seems that 45 quite innocent local residents were also killed, including 18 women and 15 children.

There were claims that the US had assisted in this raid and al-Qa’eda certainly characterised it as a ‘barbaric cluster bomb and cruise missile bombardment by American vessels occupying the Gulf of Aden’. In the beautifully simple and clear prose the organisation uses to justify its campaign of mass killing, al-Qa’eda promised more bombs on planes in response.

‘While you support your leaders in killing our women and children, understand that we have come to you with slaughter, and prepared men who love death as much as you love life. We will face you with what you cannot withstand. You will be killed as you kill, and tomorrow is not far away.’

This is the voice of the new and more radical generation of al-Qa’eda leaders, one that has torn up the old understandings with the Yemeni government — if that is what they were — and made clear it is prepared to target Yemeni politicians too. Hence President Saleh’s renewed enthusiasm for the fight.

Nasser al-Bahri told me that by his own efforts, he had persuaded some 80 Yemeni youths not to become members of the new al-Qa’eda in Yemen. Mr al Bahri, known by the nickname ‘Abu Jandal’ — ‘the killer’, was reputedly one of Osama bin Laden’s bodyguards in Afghanistan and on his return was jailed for 22 months by the Yemeni authorities. He is now involved in efforts to ‘rehabilitate’ Jihadis — or prevent new ones from joining up.

Old Jihahists do not fade away, they become business consultants in Sana’a, with a pricey leather jacket and a fashionable gold watch. And they cash in, charging journalists hundreds of dollars a time for reminiscences about bin Laden. In his office at the closest thing Sana’a has to a smart shopping centre, Mr al Bahri told me: ‘Osama has a personality different from that seen by westerners. He is a true humanitarian, tenderhearted, and inclined to humour in any crisis so as to sweeten atmosphere for his fellows. Should you get sick, he would keep attending you until you recover. He treated youths in more gentle way than a father would do.’

Mr al Bahri echoed the tribal sheikh’s warning about how disastrous US intervention would be. But he also warned of a backlash if Yemenis got to know about even the limited help being given to President Saleh, in the form of CIA trainers for Yemen’s counter-terrorism forces. ‘There is no difference between intelligence officers and military men. Both supply a legitimate reason for their death [in al-Qa’eda’s view]. Get out! Yemen has its intelligence, army and security, and it is more familiar with its territories. Al-Qa’eda in Yemen is a domestic problem, but US intervention would make the whole people become one with al-Qa’eda.’

The same realities which mean the US must, for the time being, fight only a proxy war in Yemen also mean that President Saleh does not have complete freedom of action, however much western money, arms and training he receives. Yemen is a lesson in the limits of Western power, but one learned early and therefore perhaps less expensively than in Afghanistan or Iraq.

Paul Wood is the BBC’s Middle East Correspondent

Comments