A few weeks ago, when Adolescence first came out, I found myself reading some of the academic literature on incels. It turns out they are a risk – but only really to themselves. When interviewed, over half of incels said they had considered killing themselves in the previous two weeks, compared to 5 per cent of the population who had thought about it in the past year. There isn’t much research directly linking suicide to incel culture, but we do know that the rate at which teenage boys are killing themselves is at its highest level for 30 years. Incels that kill tend only to kill themselves.

But hang on, aren’t those screen-addled teenage boys still a risk to others? A little bit, but not massively. Across the globe, there have been around 100 killings or injuries related to incel culture in the past ten years. Compare that to the 204,900 Islamist killings that have taken place during the same period and you realise these are not even vaguely equivalent issues, whatever those who run the anti-terror Prevent programme might think. And, incidentally, the government’s own research finds that incel politics is ‘slightly left of centre on average’ and that they’re disproportionately from ethnic minority backgrounds. These are not ethnonationalist white kids planning the mass murder of women. Incels aren’t evil, they’re lost – cut off from any sense of purpose.

Traditionally when men have been angry they’ve acted out. There’s a glut of sociological research about ‘young male syndrome’: seeking out conflict, a desire for destruction, high levels of risk-taking and status-seeking activity. From an evolutionary perspective, such behaviour is seen as a form of mate seeking. These biological urges are filtered through culture, sometimes with unhappy consequences. See: the promise of 72 virgins in return for extreme Islamist violence.

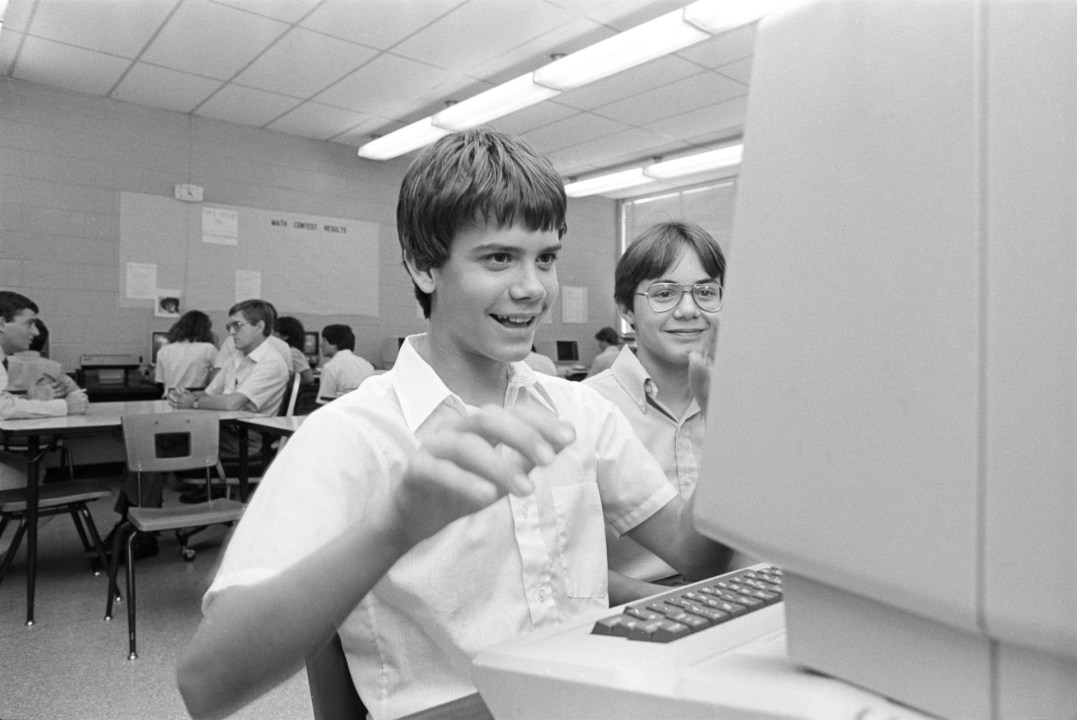

Our forefathers found ways to harness these urges, either through conscription (desire for conflict), industrial employment (displays of skill, risk taking), hunting (blood lust, also risk taking), heavy drinking (camaraderie through trial), courtship rituals (changing the rules around honour), or duelling (conflict resolution). It’s what leads soldiers to jump on grenades, killing themselves and saving their comrades in the process. Or led men to cross the South Pole. It’s still what drives young techy guys to found start-ups. Competition, endurance, honour, domination.

In the contemporary West, we’ve ended up in a place where such urges aren’t so much filtered as rejected. A few years ago I wrote a piece about toxic masculinity teaching in schools. ‘Boys are now seen as potential perverts,’ a former teacher told me, while a child psychologist said teenage boys ‘can hardly move for fear of doing something wrong’. Young males are constantly told they’re a risk, which they are. But I don’t think telling them that is particularly helpful.

The reason lies in the radical progressive beliefs of those who work in the charities and social enterprises that tend to promote notions like toxic masculinity. For example, the Global Boyhood Initiative, which seeks to deprogramme toxic schoolboys, claims that gender is ‘not tied to sex organs’. This is not an organisation grounded in biology. Many of these third sector theorists push concepts such as ‘rape culture’ and then blame their existence on capitalism or colonialism. Such male pathologies are the result of an inequitable political system, they argue, while the same behaviours also reinforce the pathologised system as a whole. (For a light taste of these arguments, see papers like ‘Toward a Queer Molecular Ecology of Colonial Masculinities’.)

Reading this stuff, one gets the sense that these academics already know their conclusion – viva el socialismo! – before they start looking at the evidence. The key argument they make, however, is that bad male behaviours are contingent rather than inherent; it’s ideology rather than biology. Spend half an hour looking at violence within primates and you’ll see that this isn’t the case. Nature is Hobbesian: we’re wired to want to fight.

As ever, the Greeks understood the importance of formalising the male desire for conflict. They had the concept of agon, which means something like contest, struggle or competition. It exhibited itself in athletics, literary competition, philosophical debate and the political sphere. Agon was seen as the source of excellence: only through competition could the best rise to the top. It is a concept that used to be more common in Britain. A criminal trial is a competition between competing views. Parliament is arranged adversarially, with the government facing the opposition, and the people choosing which is the more excellent party (don’t laugh). I can’t imagine either institution being invented today. We’re supposed to be collaborative and consultative, reaching consensus through compromise. Just look at the EU’s horseshoe parliament.

What incels seek, because of biology, is conflict

Rather than recognising the importance of open, controlled conflict, we’ve sought to remove conflict entirely. Writers such as Louise Perry and Nina Power have argued that our culture has become much more feminised since women entered the public sphere. Conflict has turned from confrontational and aggressive to surreptitious and procedural. People in offices tend not to argue in person but instead report one another to HR. Our agonic theatres have mostly disappeared. Sport is one of the few that remains, although animosity between fans is treated as a major social ill and female pundits are deployed to neutralise any risk of overt blokiness. (As it happens, sports fans are so heavily skewed male that even women’s football is more regularly watched by men than women.)

Most of the remaining arenas for combat – gaming, martial arts, testosterone-fuelled trading floors – are seen as cringe, fringe or down-right bad. Funnily enough, incels are far more likely to be drawn to these things. They love online gaming and martial arts, something that the likes of Joe Rogan promotes (a decent and all-too-rare ‘role model’, to use that irritatingly pastoral phrase). Incels are also more likely to be major risk-takers when it comes to things like Bitcoin. Cryptocurrency makes much more sense when you understand it as an agonic theatre, one that is more readily accessible to young men than the floor of the stock exchange. Be bold and you win glory and wealth. Fail, and you’re a rekt weak hand.

What incels seek, because of biology, is conflict. So what we need is a return to good masculinity. Not the type that tells you it’s OK to put on mascara, but one that channels those fighty, angry urges into something good. We need agon. Without it, incels can only rage against themselves.

Comments