‘Payday Lady is not trading at this time,’ says her website, sounding a little like La Dame aux camélias. Indeed (since I could not find her anywhere) the message may indicate that Payday Lady is not just temporarily indisposed, but has given up the game altogether. I’ll be glad to hear from her if she hasn’t.

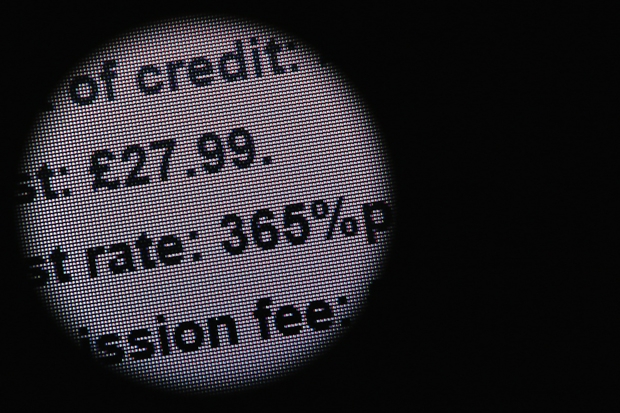

Meanwhile I can report that her rival Cash Lady (who promises she’ll be ‘here to help you’ within three minutes) was still out there — despite having her television ads banned last year — and so were Purple Payday, Pounds to Pocket, Peachy Loans, PayDay Pig and CashCowNow, all at colossal ‘representative APRs’ that look relatively cheap compared with Wonga’s notorious 5,853 per cent. But the majority of lenders in this crowded space are likely to join the lady in retirement when a strict new cap on credit terms is imposed in January by the Financial Conduct Authority — which has ordered Wonga to introduce stronger ‘affordability’ checks and write off the debts of 330,000 delinquent customers who would never have passed those tests.

Only the largest payday lenders are expected to survive the FCA’s draconian ruling — ironically including Wonga, which has some 30 per cent of the market but may have to change its tarnished branding. The implosion of this cynical sector, which grew like a mutant fungus out of the credit crunch, will be greeted with righteous satisfaction by everyone from the Archbishop of Canterbury down. But the episode should not be allowed to imprint in the public mind the modern narrative that the consumer is always a victim; yes, some naive or desperate borrowers fell into that category, but very many others just grabbed the opportunity of quick and easy injections of cash.

Consider the case, highlighted by the BBC, of 20-year-old Elliott Gomme, who ‘lied to get a £120 Wonga loan for a holiday’ and ‘felt depressed’ when he discovered his unpaid debt had risen to £800 — but is likely to be among the lucky 330,000 whose loans will be written off. Elliott, says the Beeb, thinks ‘the whole process is too simple and he wants payday lending to be banned’. But the simplicity of the process was to the company’s credit, even if the price was outrageous; it was Elliott who lied, not Wonga.

Minor embarrassments

Some corporate embarrassments are a lot less significant than others, though you might not think so from the way they’re reported and bandied about on social media. Tesco’s troubles deepen, but was there anything seriously wrong, for example, in Sainsbury’s asking staff to ‘encourage every customer to spend an additional 50p during each shopping trip between now and the year-end’? Every time I buy a coffee in Costa or Caffè Nero (I’m still boycotting Starbucks on tax grounds) and the barista says, ‘Would you like anything else with that?’ with a winning wave towards her flapjacks, as it were, I am being subjected to the simple retail science of ‘upselling’. But as a grown-up customer I am an independent moral agent, and if I buy or borrow more than I can afford in a transaction that involves no deceit or false promise by the other party, I am not a victim; it’s my fault at least as much as theirs. That principle has lately been lost in a fog of indiscriminate distrust.

Then there was the case of John Lewis managing director Andy Street, who was accused of staining his employer’s usually saintly reputation by telling an audience in London that France is ‘sclerotic, hopeless and downbeat’, a place where ‘nothing works, and worse, nobody cares’. He was, he said later, trying to be ‘lighthearted and tongue in cheek’ — but he provoked hissy fits from, among others, the French prime minister, the deputy mayor of Paris and the headline writer of Le Figaro (‘La France est finie,’ juge le patron des grands magasins anglais’). I can only suggest he takes lessons in lightheartedness from this column: I’ve been saying things like that about France for years, and my French friends all seem to agree with me.

Caring and sharing

‘The sharing economy’ sounds nice, doesn’t it? Certainly nicer than ‘the subletting economy’ or (a phrase which perhaps even Clarkson would no longer utter) ‘the black economy’. But ‘sharing’ in this new context embraces both those down-to-earth descriptions: it’s all about monetising spare rooms, car seats, parking spaces and unutilised units of labour; it’s about swapping holiday homes and trading in last year’s fashion wardrobe; it includes peer-to-peer lending, crowdfunded publishing and other platforms yet to be invented that will match one consumer’s demand to another’s supply. It has a refreshingly communitarian feel to it, even though it has already made billionaires of the likes of Travis Kalanick, co-founder of the ride-sharing service Uber, and the Californian threesome behind Airbnb, the now ubiquitous room-letting site.

The good news is that Britain aims to be ‘the global capital of sharing’. The government has asked Debbie Wosskow, creator of the self-explanatory LoveHomeSwap.com, to lead a review that will assess the potential for growth and the level of regulation needed to protect workers in this essentially informal sector while allowing it to flourish — rather than seeking to strangle it, as Germany has done to Uber.

But is there an ulterior motive behind George Osborne’s sudden enthusiasm, declared in his conference speech, for all this disruptive new-age soft capitalism? I’m grateful to investment guru Merryn Somerset Webb for explaining — as we were (naturally) sharing a picnic on a train bound for Edinburgh, where all her neighbours had been busy monetising bedrooms via Airbnb during the festival — that a huge growth in unofficial commerce of all kinds during the recession years has created what may well be a £5 billion-plus slice of the economy that is both unmeasured (meaning GDP growth has been consistently understated) and entirely untaxed. No wonder the Chancellor has set his sights on it.

Comments