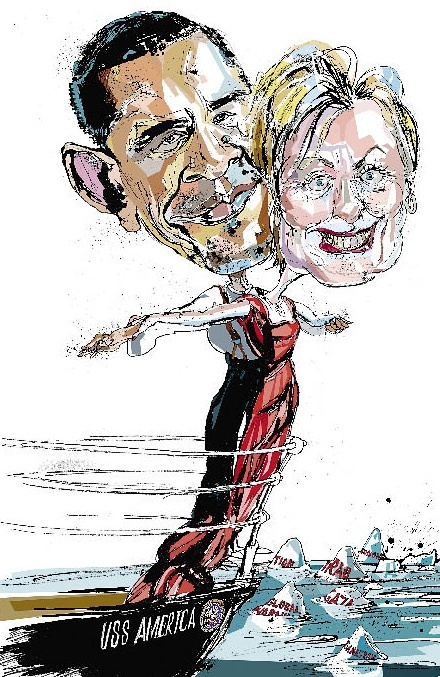

James Forsyth says that Barack Obama will need all his remarkable talents to confront an extraordinary set of challenges — not only the economy, but global security

Short of wearing a stove-pipe hat, Obama could not make his desire to be compared to Abraham Lincoln any more obvious. He plans to travel to his inauguration via the same route that Lincoln did, be sworn in on the Lincoln Bible and eat lunch off replicas of the Lincolns’ White House china. Michelle and the girls must have wondered if he was going to change their name when he took them to the Lincoln Memorial on Saturday night.

Obama has set a high bar for himself; comparisons with America’s greatest president are rarely favourable to an incumbent. Bush and Clinton both chose to set less daunting presidents as their benchmarks, Reagan and Kennedy, respectively.

But the President-elect has never been shy about setting ambitious goals. The night he sealed the Democratic nomination, he confidently declared: ‘I am absolutely certain that generations from now, we will be able to look back and tell our children that this was the moment when we began to provide care for the sick and good jobs for the jobless; this was the moment when the rise of the oceans began to slow and our planet began to heal; this was the moment when we ended a war and secured our nation and restored our image as the last, best hope on earth.’

Can Obama live up to his own words? Realistically, making it through the next four years without any major disasters would, in the present circumstances, be a great achievement and almost certainly enough to get him re-elected.

No president since Franklin Delano Roosevelt has faced such a daunting set of challenges. Domestically, Obama inherits a recession that is at risk of turning into a depression. Consumer confidence is at an all-time low — this year the deficit will probably be larger than total federal government spending in 2000, and by next year government debt will have spiked to 60 per cent of GDP; little wonder that the markets now think there is a 6 to 10 per cent risk of a US government default.

Internationally, a bellicose power that is a sworn enemy of America and its closest allies will probably be a nuclear state by the end of Obama’s first term unless action is taken to stop it. In Pakistan, the nightmare combination of a weak state, Islamic extremism, terrorists and nuclear weapons has become a reality. Peace in the Middle East seems as far away as ever and the collapse of the world economy threatens the stability of Asia and Latin America.

If the challenges are greater than those faced by Obama’s recent predecessors, so are his assets. He enters office with record approval ratings, a clear mandate and a comfortable majority for his party in both houses of Congress. At the start of his presidency, Obama will be as empowered by the nature of his election as Bush was hamstrung by his. Perhaps most valuably, Obama has what FDR called in his first inaugural address that ‘broad executive power to wage a war against the emergency’ that is implicitly accorded to the president in times of crisis.

The first order of business for the Obama administration will be the economy. In his first month in office, Obama will ask Congress to appropriate well over a trillion dollars — $350 billion as the second part of the bank bailout and a stimulus package that will cost at least $775 billion over two years. (To put that in perspective, the Iraq war has cost $597 billion.) The question is not whether Obama will get the money but how much political capital and time he has to expend to do so and how many compromises he has to make along the way.

Obama has already laid out his stimulus plan. It is distinguished by the absence of special-interest projects and its ideological heterodoxy. The plan blends together extra public spending, equivalent to about 3 per cent of GDP, and tax cuts of around 2 per cent of GDP. The proposed pump-priming has the merit of being directed to needed infrastructure — expanding broadband, alternative energy, computerising medical records and the like — rather than make-work schemes. In a break with usual procedure, Obama has said he wants it passed without ‘pork’, the local projects that normally grease the path of legislation.

Word is that Obama wants the stimulus to pass with 80 votes in the Senate. The tax cut on offer should make it possible to garner considerable Republican support. If Obama achieves this, he will have even more momentum than he does now and be perfectly positioned to make a successful effort on health care, the Democratic goal that so comprehensively eluded Clinton.

Whether Obama can achieve this depends heavily on Congressional Democrats. Already they have forced him to withdraw one proposed tax cut. The more they force him to indulge in horse-trading, the weaker his position will be, and the more Republicans will be able to oppose the package on the grounds that the President has caved in to his own side. This is such a big and risky bill that Obama needs bipartisan support; Bill Clinton passed a far smaller economic package in his first year with only Democratic support to disastrous effect.

It will be tempting for Obama to be completely focused on the economy in his first year. But that would be a mistake; the state of the world does not allow him that luxury.

There are three known foreign policy dangers that will, along with the economy, determine whether or not his first term is a success. First is the risk of Pakistan becoming a failed state. There is actually not much America can do about this, save be prepared for the worst-case scenario of a nuclear-armed country with a terrorism problem descending into chaos.

On the second challenge, stopping Iran from going nuclear, Obama has far more options. It is crucial that he embarks on direct diplomacy with Iran early on in his presidency: he’ll need as much time as possible to build domestic and international support for more forceful action, should that prove necessary. Obama will never have more diplomatic capital than he does at the beginning of his presidency, and he should be prepared to spend the bulk of it on persuading other countries to join a blockade of Iran if Tehran will not peaceably abandon its nuclear ambitions (Iran imports its petrol, so a blockade would cripple the country).

Finally, Obama needs to accomplish his promised pull-out from Iraq without squandering the gains of the surge. Ironically, it is Iraq — the issue that propelled Obama to the nomination — that is the least of the difficulties facing him.

If in 2012 the economic recovery is well underway, the budget is heading back into balance, Iran’s nuclear ambitions have been thwarted and Iraq is relatively stable, Obama can call his first term a success. His more grandiose goals can be left to his second term. It is upon Obama’s ability to steer America through the stormy present that all else chiefly depends.

Comments