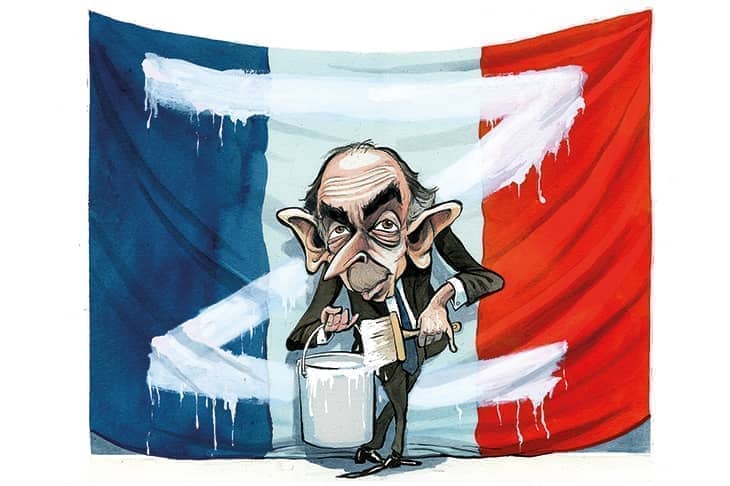

Eric Zemmour is back. The bogeyman of French politics spent the summer licking his wounds after his far-right Reconquest party was wiped out in June’s parliamentary elections, but on Sunday he addressed several thousand supporters at a rally in the south of France.

It is, hopes Zemmour, an opportunity to relaunch his political career and judging by his recent media appearances he won’t be watering down his right-wing rhetoric. Railing against immigration, environmental extremists and the sanctions on Russia, Zemmour picked up from where he left off in the spring. When it was put to him by one interviewer that he had paid the price electorally for focusing too much on immigration, Zemmour replied: ‘I was wrong electorally, but history will prove me right.’

The summer has certainly provided plenty of grist to Zemmour’s mill. Hundreds of illegal immigrants continue each week to breach France’s border with Italy, while the streets are becoming ever more violent. Zemmour has coined a new word to describe this phenomenon – ‘Francocide’, claiming that the victims are usually French and the perpetrators immigrants.

Those activists who have come into contact with Zemmour complain of the ‘autocratic’ way he runs his party

Zemmour’s rhetoric resonates with many more than the 2.5 million voters who cast their ballot for him in the first round of the presidential election, but what holds him back is himself. He has never been particularly popular with female voters, many of whom regard him as sexist, while those activists who have come into contact with Zemmour complain of the ‘autocratic’ way he runs his party. But his gravest failing is his disdain for the working class.

It was reported at the end of June that Zemmour blamed his political failure on the ‘illiterate working class’. It wasn’t that his message was too narrow, focusing almost entirely on immigration and Islam, with nary a word to say about the burgeoning cost of living crisis. No, apparently his intellect was lost on the thick hoi polloi.

Last week one of the most prominent figures in the yellow vest movement, Jacline Mouraud, announced she was leaving Zemmour’s party because of its leader. ‘The French are neither illiterate, nor uncultivated, nor toothless,’ she said. ‘One cannot claim to want to save France if one doesn’t love the French.’

Despite his political travails, Zemmour remains a favourite with television studios. Like Donald Trump in America, Zemmour’s rants boost ratings but unlike Trump, they don’t translate into votes. That’s because Trump talks to his voters, and not down to them. Zemmour’s only hope of political survival is an alliance of sorts with the centre-right Republicans, who are in the process of electing a new president. They have always been more of a fit for Zemmour than the National Rally because they are middle-class and more economically liberal than Marine Le Pen’s party.

The two leading candidates for the Republicans’ presidency, Bruno Retailleau and Eric Ciotti, have in recent days distanced themselves from the prospect of any form of coalition with Zemmour. ‘The ideas of the right are the majority in the country, but others have hijacked them, both in government and on the far right,’ said Ciotti, referring to a recent report that stated the French electorate leans more in that direction than ever. ‘When the right is right-wing, there is no room for the far right.’

Ciotti, an MP in Nice, embodies the right-wing of the Republicans, and realistically his election as president is the only way the party can remain relevant. He is uncompromising on immigration, crime and Islamism, though unlike Zemmour he is at pains to draw a distinction between Islam the religion and Islamism the political ideology.

Nonetheless, there is a centrist element within Republicans who regard Ciotti as ‘Zemmour-lite’ and they have said they will quit the party if he is elected president.

Where would they go? To Macron, who has lured a number of high-profile Republicans to his party in recent years including his finance and interior ministers. The Republicans can resurrect themselves under Ciotti if they return to being socially conservative and economically liberal. Their mistake in recent years has been to believe that the best way to counter Macron is to copy him. But Macron is at heart a centre-left progressive, a European first and a Frenchman second. In moving towards the centre in the last five years, all the Republicans have done is see their representation in parliament plummet from 112 seats to 61, fewer than Le Pen’s 89 MPs.

They need now to head in the other direction, away from the centre towards the right without straying too far into Zemmour territory. As for Zemmour, his TV appearances will continue to scandalise the chattering classes but in all likelihood he will make way in the next year for the vice-president of his party, Marion Maréchal, the former National Front MP and the niece of Marine Le Pen. She has also been on television this month, deftly sidestepping questions about Zemmour’s suitability to lead the party. The pair have a similar outlook on life but Maréchal’s advantage is that her appeal cuts across age, sex and class. She is also politically literate, unlike Monsieur Zemmour.

Comments