Books and Arts – 6 September 2018

The good, bad and ugly in arts and exhbitions

To have been a black lawyer in the deep south of America in the early 1960s would have taken a level of courage well beyond the ordinary. Chevene Bowers King was just such a man. He could have worked in the desegregated north, but instead chose to risk his life in Georgia, defending black people imprisoned on trumped-up charges and organising non-violent demonstrations to end segregation. David Morley’s two-part play on Radio 4, The Trials of CB King, took us through the blatant racism, the everyday brutality and dangerous reality for the black citizens of Albany, Georgia, where the sheriff encouraged the police to beat up the innocent purely because

This adaptation of Anton Chekhov’s play is handsomely mounted, as they say, and features a stellar cast (including Annette Bening, Elisabeth Moss and Saoirse Ronan), but it won’t be setting the world alight. It is not a waste of 90 minutes, and Bening is superb, as if you even needed me to tell you that. But it doesn’t especially distinguish itself otherwise and I kept waiting for it to deliver emotionally. I waited and waited and waited, but no, nothing. The film is, of course, set on a country estate just outside Moscow, because if it weren’t set on a country estate just outside Moscow it plainly wouldn’t be Chekhov.

This week was bad news for fans of good television drama series — mainly because there’s now three more of the things to keep up with if you don’t want to feel left out of office conversations. The one that stirred up the most advance media excitement was Wanderlust (BBC1, Tuesday), on the traditional grounds that it promised to be unusually explicit about sex. And in that, it certainly didn’t disappoint. The first episode began with a flurry of masturbation (not a phrase I can remember using in a TV column before). First, Joy, a middle-aged therapist, slipped a hand beneath the morning bedclothes — until her teenage son came

It’s intelligent, enjoyable, beautiful to look at and funny in unexpected places, yet Othello at the Globe didn’t quite meet my sky-high expectations. The star should be the Moor but André Holland, from Alabama, can’t rival the magnetism of Mark Rylance (Iago). Holland’s diction is a strain for British ears. We’re used to hearing consonants bashed out — rata-tat-tat — like a rifle range, but his looser southern accent made some of his lines indistinct. Stately Jessica Warbeck lacks Desdemona’s impulsive streak and she plays her as a mature and self-possessed recipient of several Businesswoman of the Year awards. It was strange to see this matriarchal figure meekly assenting to

Reports of the death of bookstores are fiction. In 1931, there were about 4,000 bookstores in the United States. Almost all of them were gift stores, selling a limited stock of paperbacks. Only about 500 of them were specialist bookstores, and almost all of them were in major cities. True, between 1995 and 2000, the number of independent bookstores collapsed by 40 per cent. Amazon opened for business in 1994, but two other factors were big-city gentrification, and the expansion of mediocre chains like Barnes & Noble and Borders, which went public in 1995. Now, the big chains are gone — and who, apart from a homeless person looking for

Not so long ago, the Dundee waterfront was presided over by a great triumphal arch, built to commemorate Queen Victoria’s visit in 1844. It was an imposing piece of decorative architecture, 84 feet high, and it dominates most views of the city painted over the ensuing century. It became a cherished symbol of Dundee but in 1964 they knocked it down and used the rubble as infill for a thuddingly insensitive road system that would effectively destroy the southern face of the city. Mary Shelley stayed in Dundee in her youth and later wrote of the ‘blank and dreary’ northern shores of the Tay. It’s a description still familiar to

In 1675 Lady Bedingfield wrote to Robert Paston, first Earl of Yarmouth. Never, she exclaimed, had she seen anything so fine as the latter’s mansion, Oxnead Hall. It was ‘a terrestriall paradise’, the ‘gardens so sweet — so full of flowers’, the house so clean. ‘Nor,’ she concluded, ‘did I ever in my life find anything in poetry or painting half so fine.’ Almost all this splendour vanished long ago. But its essence survives, compressed into a single painting, ‘The Paston Treasure’, currently the centrepiece of an exhibition at Norwich Castle Museum. It is a cornucopia of baroque bric-à-brac, crammed with a jumbled abundance in which curvilinear tropical shells, ornate

Cassian Harrison, the editor of BBC Four, told the Edinburgh International Television Festival last week that no one wants to watch white men explaining stuff on TV any more. ‘There’s a mode of programming that involves a presenter, usually white, middle-aged and male, standing on a hill and “telling you like it is”,’ he said. ‘We all recognise the era of that has passed.’ I’ve been puzzling over this. Why would one of the Beeb’s most senior executives, himself a white, middle-aged man, say something likely to antagonise such a large number of the people who pay his £170,000 salary, i.e. licence payers? After all, 87.2 per cent of the

Non-stop chatterbox and mystifyingly revered fabricator of sub-Chekovian paddywhackery, Brian Friel has received another production at the Donmar. His play Aristocrats cadges shamelessly from Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard. The setting is a crumbling mansion in Donegal occupied by four adult members of the O’Donnell clan (three girls, one boy), who idle around the place waiting for Dad to clock out so they can get their mitts on the bricks. Lindsey Turner’s production is curiously stripped of ornament. The characters are assembled on a lime-green patio, suggestive of mown grass, which is surmounted by a white frame with the dimensions of the goalposts at Wembley. To represent the mansion

Yardie is Idris Elba’s first film as a director and what I have to say isn’t what I wanted to say at all. I love Elba and wanted this to be terrific. I wanted him to be as good from behind as he is from the front, so to speak. I wanted this to absolutely smash it as a narrative about the Jamaican-British experience as there have been so few. But, alas, it is a disappointment. It is patchy. It’s not paced excitingly. The characters are insufficiently drawn. And I struggled with the thick Jamaican patois, I must confess. I was often muddled, yet whether it was due to that

Here’s a thought. Matthew Bannister, former Radio 1 controller turned presenter of programmes such as Outlook on the World Service and Radio 4’s The Last Word, has just announced that he’s leaving Outlook, which goes out several times a week, to ‘join the world of podcasting’. In fact, he’s already launched his own podcast, Folk on Foot. It’s as if he now believes that podcasting is where the exciting new challenges in audio (note, not broadcasting) can be found. We wireless-lovers should pay attention. Bannister is a radio man through and through. Does he really believe that podcasting is the future? We’re still waiting for the podcast that truly challenges

All the good non-fiction things that were ever on TV — from Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation to David Attenborough’s Planet Earth (the bits where he’s not proselytising about climate doom, I mean), from Andrew Graham-Dixon’s arty jaunts to Italy to Jonathan Meades’s bizarro forays into architecture, from The World at War to all those more recent war porn documentaries narrated by Sam West, from Werner Herzog’s Little Dieter Needs To Fly to Louis Theroux doing a number on Jimmy Savile — have one thing in common: they were all made by middle-aged men. Middle-aged men are the business. They’re comfortable in their skin; they’ve got hinterland and character; they’ve put in

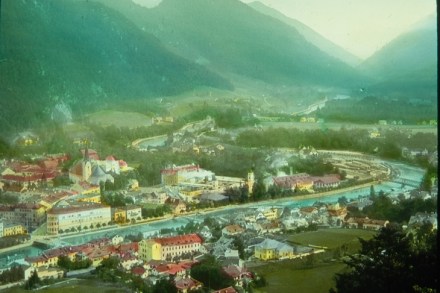

It’s the lederhosen that grabs you first. Two gents were walking down the street ahead of us in full Alpine rig: long socks, collarless loden jackets, and hunting hats decorated with what looked like shaving brushes. Among the flowerbeds and fountains that surround the main theatre of the Bad Ischl Lehar Festival a posse of young women crossed our path, all wearing embroidered dirndls and laughing. By the time we took our seats in the auditorium, we were grappling with a deeply un-British notion: that none of this was ironic. We weren’t at Glyndebourne any more. But if you love the much-mocked art of Viennese operetta, a forgotten spa town

‘It is disastrous to name ourselves!’ So Willem de Kooning responded when some of his New York painter buddies elected to call themselves ‘abstract expressionists’. He had a point. Labels for movements — such as pop art, impressionism and baroque — are almost always misleading and seldom invented by the artists themselves. That was certainly the case with the idiom examined in a little exhibition at Tate Modern, Magic Realism: Art in Weimar Germany 1919-33. Actually, this rather heterogeneous assortment of painters has two tags. In 1925, a critic named Franz Roh came up with a nice phrase, magischer Realismus, which was later borrowed to refer to various writers, including

For recovering teetotallers, like me, Thinking Drinkers is the perfect Edinburgh show. On stage, two sprucely dressed actors perform sketches about booze while a team of well-trained ushers race around plying the audience with strong liquor from plastic beakers. In under an hour, I swallowed a can of ale chased by vodka, gin, rum and Irish whiskey. It’s a decent show but, for obvious reasons, forgettable. Nina’s Got News is the first fringe play written by Frank Skinner. Nina has split up with her besotted boyfriend, Chris. When he answers a summons to her flat he’s hoping for a valedictory romp. But Nina has asked her best pal Vanessa over

Not the most beguiling of titles, I admit, but The Secret Life of Landfill: A Rubbish History (BBC4, Thursday) was a genuine eye-opener. The programme began with Dr George McGavin proudly announcing that ‘What we’re about to do has never been attempted on television before’: a claim that it’s usually best to treat with some scepticism, but that here seemed hard to deny. Certainly, I can’t remember another TV documentary in which the presenters spent 90 minutes digging through (non-metaphorical) rubbish. At first, the mood was one of rather determined excitement. McGavin twinkled away Scottishly behind his half-moon specs as he bombarded us with statistics about the hundreds of tons

The Children Act is the third Ian McEwan film adaptation in 18 months (after The Child in Time and On Chesil Beach), and if you’re minded to think no amount of Ian McEwan is too much Ian McEwan then you are wrong. This is very Ian McEwan: tasteful, restrained, high-minded, controlled. Once, fine. Twice, fine. But by the third time you will want to take all that tasteful, high-minded, controlled restraint and put a rocket under it. Or at least I did. Directed by Richard Eyre, and adapted by McEwan, the film stars Emma Thompson, who is outstanding, and will keep you gripped to the extent that you can be

Like most of our ape ancestors, we have really had only one response to the fall of night. We have stretched and yawned, we have climbed upwards, we’ve lain down somewhere soft, closed our eyes and shut the whole thing out until morning. Humans may have exchanged tree trunks for a set of stairs, and bunches of green leaves for sprung mattresses, but the same basic reflex has been ongoing among large primates for four million years. The new exhibition at the Natural History Museum, Life in the Dark, reveals to us a little of what and who we have been missing as a result of our diurnal bias. Not