Books and arts – 2 November 2017

The good, bad and ugly in arts and exhbitions

This is not Midsomer Murders. The new film adaptation of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express is thick with violence and sexual innuendo. It elevates Hercule Poirot, the diminutive, fastidious Belgian detective, with his egg-shaped head and pot belly, to part-time action figure, a man who chases bad guys down dizzying descents in exotic snowscapes before straightening his magnificent moustache with a twinkle in his eye. This is less cosy, golden age detective fiction than a cross between Daniel Craig’s 007 and Scandi noir. Kenneth Branagh, who stars and directs, has brought his experience playing the dejected Swedish police inspector Wallander to the fore, giving the usually reserved detective

Mandy was 38 when she was told she was ‘in the end stage’, suffering from COPD and finding it more and more difficult to breathe. Matthew, in his twenties, was given just four to five years of life after being diagnosed with a brain tumour. Vivek, also in his twenties, is confined to a wheelchair because he suffers from Duchenne muscular dystrophy and is already reliant on a ventilator for much of the time. Sophie has stage four lung cancer and tumours in her lungs, lymph nodes, bones and brain. You might think a programme made up of their thoughts, words, experiences would be one of lament and moping, misery

You know where you aren’t with director Yorgos Lanthimos. The Greek allegorist creates parallel worlds which superficially resemble our own. In Dogtooth an overweening patriarch incarcerates his three adult children in a state of infantilised innocence. The Lobster punishes those unable to find a mate by transfiguring them into animals. His acerbic commentaries on flawed modernity feel like lurid horror stories the ancients forgot to write down. The Killing of a Sacred Deer invokes pagan sacrifice in its title. Iphigenia is even mentioned in dispatches — the subject of a schoolgirl essay that doubles as a mythological flare. The film opens on a close-up of open-heart surgery in which a

Anybody who wants to maintain a strong and untroubled stance against mass migration to Europe should probably avoid BBC2’s Exodus: Our Journey Continues. In theory, the case for limiting the numbers may be more or less unanswerable — but this is a joltingly uncomfortable reminder of what it can mean in practice. Any viewers suspicious of the BBC’s pinko tendencies will presumably have noticed that all the refugees we’ve met so far are completely lovely. Yet, faced with Thursday’s episode, even they might have found it tricky to preserve a steely primacy of head over heart. Or not to notice that these are people very much like us — only

Bang! A brand new theatre has opened on the South Bank managed by the two Nicks, Hytner and Starr, who ran the National for more than a decade. Located near a river crossing, their venture bears the unexciting name ‘Bridge’. If these two adopted a child, they’d call it ‘Orphanage’. Visitors approach along the Thames embankment and arrive at a soaring cliff of glass whose revolving doors usher them into a large anonymous foyer. It feels like a student union bar or a bit of an airport. Dangling from the ceiling are dozens of light bulbs, their radiance muted with tea-stained shades that cast an absolving glow over facelifts, hairpieces

According to the accountants’ ledgers, DVDs are dying. Sales of those shiny discs, along with their shinier sibling the Blu-ray, amounted to £894 million last year, which is almost a fifth lower than in 2015 and less than half of what was achieved a decade ago. And last week we finally said goodbye to the postal DVD service Lovefilm, too. The explanation for this decline is the explanation for many modern declines: digital is taking over. Nowadays, downloads and streaming services make more money than the old physical formats. But accountants don’t know everything. From a different perspective, through the bloodshot eyes of a cinephile, DVDs are thriving — and

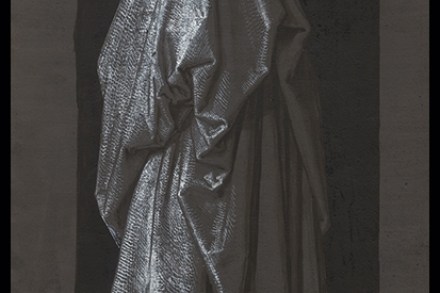

ENO has revived Richard Jones’s production of Handel’s Rodelinda. It was warmly greeted on its first outing in 2014, though Jones was, as he remains, inveterately controversial. The opera itself seems to command universal admiration among Handelians, and widespread approval among those of us who have never quite managed to call ourselves that. The most unequivocally positive response I’ve had to it was at Glyndebourne in 1998, where it was produced as if it were an early black-and-white film, and superbly conducted by William Christie. Viewing the DVD has confirmed my warm feelings about it. My chillier feelings about ENO’s in many ways excellent account are prompted, first, by Jones’s

It’s hard to admire communist art with an entirely clear conscience. The centenary of the October revolution, which falls this month, marks a national calamity whose casualties are still being counted. When my father-in-law comes to visit, I have to hide my modest collection of Russian propaganda: he grew up under the Soviets and has few fond memories of the experience. He can’t work out why old agitprop is so popular today. But the simple fact is, for all the disaster they wrought, the Bolsheviks did leave a legacy of images so striking that, even now, they can draw thousands into a museum. As Tate Modern is about to demonstrate.

In the 1880s the young Max Klinger made a series of etchings detailing the surreal adventures of a woman’s glove picked up by a stranger at an ice rink. At a certain point the glove washes up, nightmarishly large, beside a sleeping man’s bed on to which a shipwrecked sailor is desperately hauling himself. Storm-tossed billows merge with rumpled pillows in an image simply titled ‘Angste’. Klinger’s nightmare vision came back to haunt me at the exhibition Tracey Emin, ‘My Bed’/JMW Turner. Yes, you read that right. Since its loan to the Tate in 2015, Emin’s most famous oeuvre has been partnered in exhibitions with the work of Francis Bacon

Luigi Cherubini is the pantomime villain of French romantic music. As head of the Paris Conservatoire in the 1820s he was the embodiment of obsolescence: Berlioz’s Memoirs recount an occasion when some state functionary told the ageing master that he should really write an opera. ‘One can dimly imagine the indignant consternation of the author of Medea, Les deux journées, Lodoïska, Mont Saint-Bernard…’ writes Berlioz with twinkling malice, though most modern operagoers, if they’re honest, won’t be any wiser. The one exception is Medea, which has never quite dropped into obscurity. Fiona Shaw’s new production at the Wexford Festival shakes it brusquely back to life. We’re at a hen party

Ballet would have been an obvious revenue stream for Sadler’s Wells when it reopened back in 1998 but straight-up classics have been few and far between over the past two decades — the Rothbart of the Royal Ballet of Flanders’ Swan Lake wore a live owl on his head. And yet, while the theatre’s programming fights shy of tutus and toe shoes, its fiercely contemporary output can sometimes bridge the notorious gulf that has traditionally divided classical and contemporary audiences. Wayne McGregor has been resident choreographer at the Royal Ballet since 2006 but combines this role — and countless international projects — with his directorship of his own company, whose

Beginning starts at the end. A Crouch End party has just finished and the sitting room is a waste tip of punctured beer cans, tortured napkins and crushed nibbles. Wine bottles lie scattered across the carpet like fallen ninepins. Hostess Laura invites her last guest, Danny, for a final glass of Chardonnay. Twitchy conversation ensues. Then she tells him point-blank that she’s fallen in love with him, even though they’ve only just met. He rejects her weird come-ons (‘Kiss me, you lemon’) with evasive hyperactivity. He dashes about the room filling a bin-liner with defunct wine bottles and pulverised cheesy Wotsits. She forces him to sit next to her on

The early 1970s was football’s brute era of Passchendaele pitches and Stalingrad tactics. The gnarled ruffians of Leeds United — wee hatchet man Billy Bremner, the graceful assassin Johnny Giles, Norman ‘Bites Yer Legs’ Hunter — embodied the age. Not that you’d guess this from the badge on the club’s shirt: the letters LU were styled into a grinning emoji in goofy yellow. In 1973, the club kit (pristine white, which they had changed to a decade earlier to mimic the lordly Real Madrid) was designed by Admiral, the company that dreamed up the wallet-emptying concept of the replica shirt. Admiral went in for hectic piping and busy collars. They

In the first scene of this distinctly odd documentary, Grace Jones meets a group of fans, who squeal with delight at the sight of her and nearly pass out with excitement when they hear her speak. And that, I suspect, is the effect which the film confidently expects to have on the rest of us. OK, it seems to be saying, so you’re not going to learn how Jones got from the Jamaican childhood we see her revisiting to the globetrotting life we see her living now. OK, so there’s no structure, sometimes no clue as to where scenes are taking place or who the other people in them might

Even in a Trump world where reality is what you say it is, the London Symphony Orchestra’s announcement of a new concert hall occupies a bubble of pure fantasy. New York architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro have been awarded a contract for a project that has no funding. Concert hall, what concert hall? The only cash on the table is £2.5 million from the Corporation of the City of London. The hall is hot air. There has been no public consultation, no actuarial study of demographic need, no consideration of best possible sites or size. There is not even a consensus within the classical sector that a new hall is

Only Neil MacGregor could do it — take us in a single thread from a blackened copper coin, about the size of a 10p piece, dating from Rome in about 200 AD, to a packed music hall in London during the first world war. In his new 30-part series for Radio 4, Living with the Gods, the former director of the British Museum looks at the ways in which societies come together through shared rituals and beliefs and how these rituals are developed and used to make sense of our place in a universe beyond human comprehension. One side of the coin shows a fire burning within the Temple of

I’m sitting across a café table from a young man with a sheaf of drawings that have an archive look to them but are in fact brand new. His Jacob Rees-Mogg attire — well-cut chalk-stripe suit and immaculate tie — sets him apart from the others in the room, who are mostly architects and architectural fellow travellers like me. We don’t dress like that. But George Saumarez Smith is indeed an architect, a very good one. He just happens to be a trad. A traditionalist, mostly a classicist. And now is very much the time of the architectural trads. They have crept up on us. There’s a revival going on,

Madame Monet was bored. Wouldn’t you have been? Exiled to London in the bad, cold winter of 1870–71. In rented rooms above Shaftesbury Avenue, with a three-year-old son in tow, a husband who couldn’t speak English, and no money coming in. Every day roast beef and potatoes and fog, fog, fog choking the city. ‘Brouillardopolis’, French writers called it. Camille Monet had offered to give language lessons, but when she hadn’t a pupil — and Claude hadn’t a commission — she let him paint her, listless on a chaise-longue, book unread on her lap. Her malaise was ‘l’exilité’ — the low, homesick spirits of the French in England. ‘Meditation, Mrs