Dramatic effect

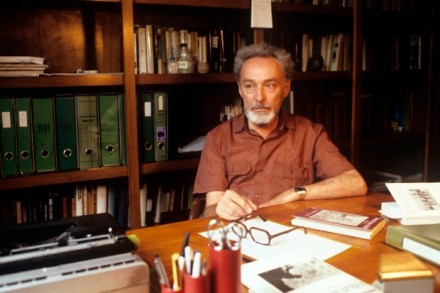

It was hard to believe that Monday morning’s introduction to the Italian writer Primo Levi on Radio 4 lasted for only 15 minutes. It was so rich, multi-layered, filled with meaning. Presented by Janet Suzman, it was intended as a fanfare for the 11-part adaptation of Levi’s most original book, The Periodic Table, in which he explores the chemical elements by equating them to episodes in his own story. Levi, an Italian chemist, was captured by the Nazis as a resistance fighter and a Jew, and at first detained and later sent to Auschwitz. His science training and his knowledge of German saved him from the gas chambers; and a