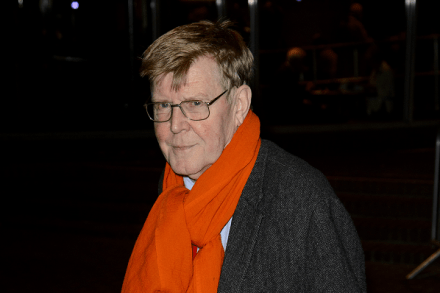

Alan Bennett shows how hypocrisy is a National issue

Alan Bennett announced on Radio 4 last week that ‘hypocrisy’ is the defining characteristic of the English. ‘In England, what we do best is lip service,’ he sighed, before going on to admit that even he is a hypocrite. While many have taken issue with his claim, Mr S was reminded of Bennett’s words on a recent trip to the National Theatre. The playwright – a Primrose Hill millionaire who claims to hate rich privilege – has just penned a fluffy essay about soon-to-retire National boss Sir Nicholas Hytner (who just happens to have used public money to stage Bennett’s latest play People). The essay appears in programmes at the National and gushes that