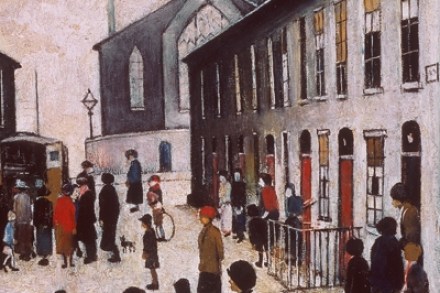

At last! The snobbish Tate has finally overcome its distaste for L.S. Lowry

One day in Berlin, I saw the rerun of the RA’s Young British Artists exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin’s equivalent of Tate Modern. After that, I saw a superb retrospective of Lyonel Feininger at the Neue Deutsche Galerie. In the evening, I ran into the onlie begetter of the YBA show (which, with the exception of Ron Mueck’s amazing sculptures, had not given me much pleasure), my (unrelated) namesake Norman. I had no wish to discuss Norman’s pride and joy, the YBA, so turned the conversation to Feininger and asked whether Norman had seen it. ‘Ah,’ said Norman, ‘what a bore; I won’t waste my time on him.’ After