The best radio at the moment is on the BBC World Service

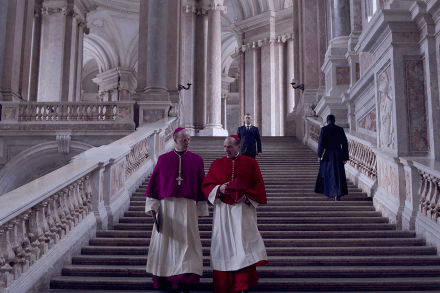

Online viewings of Conclave increased threefold following the death of Pope Francis last month. At least some of the traffic was rumoured to have come from the Vatican itself. This raises many questions, but the most pertinent for me this week is, what did the cardinals think of the carpets? Do they really have coffee machines in their rooms like Tremblay? Minibars like Bellini? Their peace spoiled by the sounds of a lift shaft as in the case of long-suffering Lawrence? If any of these details passed you by, it’s worth watching the film again. In fact, after listening to an interview with the production designer, to be broadcast on