Sacrificing art for ideas

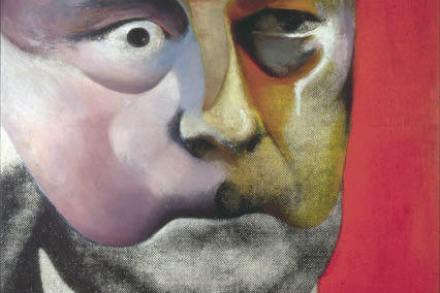

Richard Hamilton: Modern Moral Matters Serpentine Gallery, until 25 April This year is the 40th anniversary of the Serpentine Gallery, that most welcoming of exhibition venues — the gallery in the park — with its wide views and well-appointed rooms. Expectation rises as the visitor walks through gardens burgeoning with spring, even if it is raining. To start its anniversary year, the Serpentine has mounted an exhibition of Richard Hamilton’s political work entitled (in homage, presumably, to Hogarth) Modern Moral Matters. The show is a real disappointment: the blinds are down to focus the visitor’s attention inward, which might be acceptable if there were riches to be seen. Instead, the