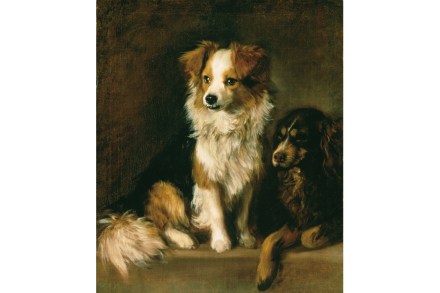

Artists’ dogs win the rosettes: Portraits of Dogs – From Gainsborough to Hockney, at the Wallace Collection, reviewed

Walking on Hampstead Heath the December before Covid, I got caught up in a festive party of bichon frises dressed, like their owners, in Christmas jumpers. It seemed bizarre at the time but wouldn’t surprise me now. During lockdown the local dog population exploded and the smaller breeds now wear jumpers all winter. There are no dogs in jumpers in the Wallace Collection’s new show – though, given the level of anthropomorphism, there might as well be. The ‘Allegorical Dog’ section, devoted to Edwin Landseer, includes ‘Trial by Jury’ (c.1840) with a poodle sitting as judge, and a canine interpretation of the parable of Dives and Lazarus featuring a well-fed