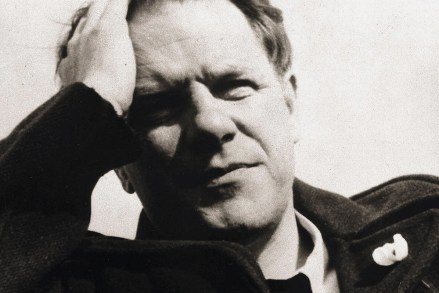

One of the boys: From Scenes Like These, by Gordon M. Williams, reviewed

Although Gordon M. Williams died as recently as 2017, his heyday was the Wilson/Heath era of the late 1960s and 1970s. During that time he managed to appear on the inaugural Booker shortlist, dash off a ten-day potboiler, The Siege of Trenchard’s Farm, that would be filmed by Sam Peckinpah, and continue to file a series of ghost-written newspaper columns for the England football captain Bobby Moore. As these accomplishments might suggest, Williams was the kind of writer whom the modern publishing world no longer seems to rate. Essentially, he was a literary jack-of-all-trades, alternating straightforward hackwork with more elevated material as the mood took him, and eventually abandoning fiction