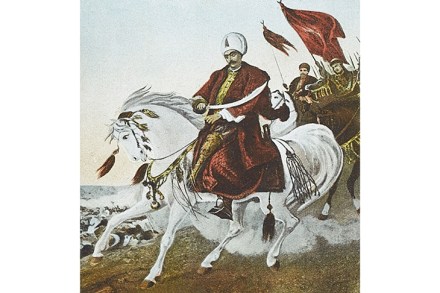

In just eight years Selim I became ‘God’s Shadow on Earth’

Faber must take a rather dim view of British readers’ historical awareness these days. This is a biography of one of the greatest Ottoman sultans in the empire’s 600-year history, yet the publishers cannot bring themselves to mention his name in the book’s title. Perhaps they thought Selim I was too obscure, and maybe they’re right, but their reticence is not shared by Alan Mikhail’s American publishers, who rightly give the sultan his due. Never mind. Mikhail, chair of Yale’s history department and a specialist in Ottoman history, makes it his mission to demonstrate how this utterly compelling leader helped define his age, bending the world to his will. And