Duplicity of the first order

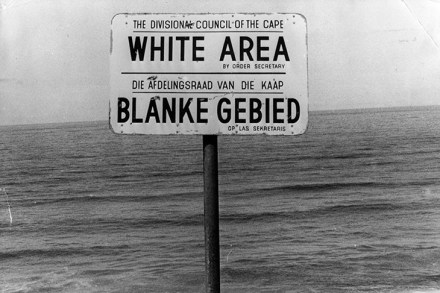

Around 1970 I was labelled ‘Public Enemy No. 1’ by white South Africa’s newspapers for leading militant anti-apartheid protests which stopped all-white sports tours to Britain. And a year ago when, under parliamentary privilege in the House of Lords, I exposed looting, corruption and money-laundering by former President Zuma and his cronies the Gupta brothers, some jaundiced white South Africans again attacked me — this time for having helped deliver ‘corrupt black majority rule’. They should read Hennie van Vuuren’s fine book, which tellingly concludes: The current struggle against [Jacob Zuma-inspired] corruption in South Africa is undermined by a basic lack of appreciation of the nature of that corruption and