Father of the nation

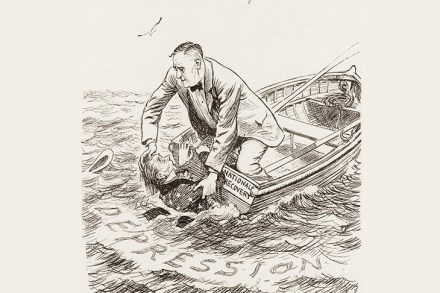

Franklin D. Roosevelt isn’t as popular as he once was. When Barack Obama won the 2008 election, he let it be known that he was reading a book about FDR, and tumbleweed blew through the newsrooms. Which is odd because for many decades FDR was every bit the model liberal as Ronald Reagan was the model conservative. Roosevelt was credited with ending the Great Depression, laying the foundations of a welfare state and leading America through the second world war — achievements for which he was rewarded with not one, not two but four election victories. And he did all of this despite being an elitist East Coaster with a