Only obeying orders | 12 January 2017

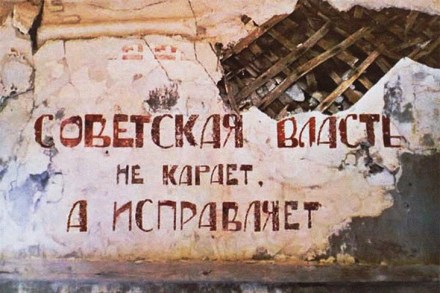

Spare a thought for the poor Gulag guard: the rifleman standing in the freezing wind on the outside of the wire, almost as much a captive of the Stalinist prison machine as the inmates he’s guarding. Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Evgeniya Ginzburg and Varlaam Shalamov have left the world a rich, searing portrait of the Gulag from the point of view of the prisoner. But the diary of Ivan Chistyakov is unique — a narrative of the brutal conditions in Stalin’s Gulag, told from the point of view of one of the captors. Chistyakov was a senior guard at the Baikal-Amur Corrective Labour Camp or BAMLag, and he wrote his personal diary