Recent crime fiction | 29 September 2016

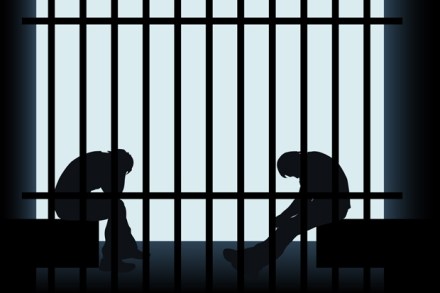

There are two people in a prison cell: Frank and Hal. One of them is a member of a spy ring planning a terrorist act; the other is a police agent planted there to befriend the spy, and gather information on the terrorist cell. But the reader doesn’t know which is the cop, and which the criminal. This is the brilliant conundrum at the heart of Frédéric Dard’s The Wicked Go to Hell (Pushkin Vertigo, £7.99). The relationship between the two men moves from mutual loathing, suspicion and violence, to a begrudging partnership, to friendship, then to suspicion once more. Even after they escape prison together and go on the