If Cameron is deleting all No. 10 emails, who will write his history?

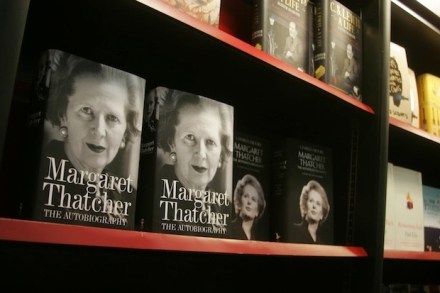

This is an extract from Charles Moore’s Notes in this week’s Spectator, out tomorrow. Subscribe from just £1. In a few weeks, I shall have finished the second volume of my threepart biography of Margaret Thatcher. I am now at the checking and revising stage — 3,000 endnotes to be made shipshape, 2,000 quotations to be cleared with interviewees, 300,000 words to be re-imagined as if read fresh. This involves the exchange of scores of emails every day. The question arises, ‘How did enterprises of this kind ever happen before computers?’ The answer, I think, is that the sources used were much narrower than they are today. Authors were extremely dependent on where