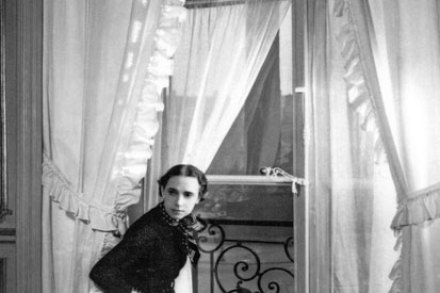

Nicky Haslam on sharing a lover with Elsa Schiaparelli and the endearing punk of Vivienne Westwood

A comet streaked into France in the 1930s, its fallout sending the staid echelons of haute couture into a tailspin. A mere 30 years later a rogue missile blasted into London, blowing dainty English clothes sense to smithereens. Both these thunderbolts shot the stuffing out of cloying conventionality, one with an arrow-narrow silhouette, the other by blitzing the luxe out of luxury, the ex out of exclusivity. It’s worth studying the photographs of those two alien invaders, the subjects of these lengthy works. The young Elsa Schiaparelli, sleek-headed, confident, wearing strict black: and the young Vivienne Westwood, with tousled hair and a workaday high-street suit: both have intense dark eyes