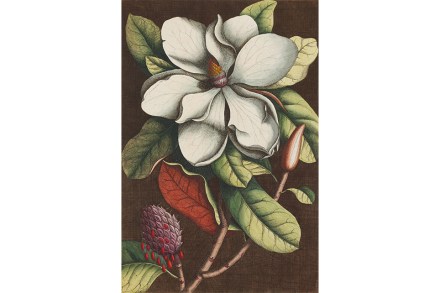

The North American fruit tree that provides a model for economics

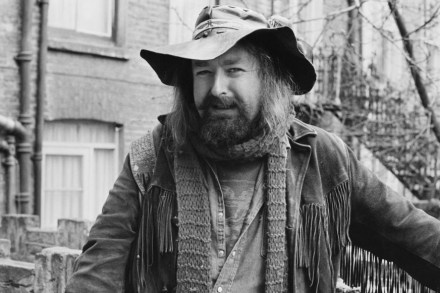

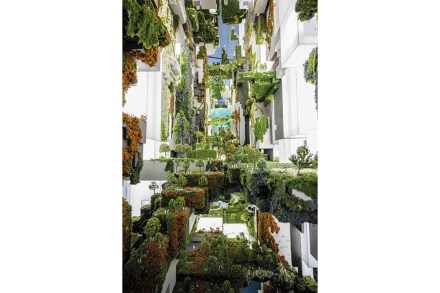

Life on Earth is not a zero-sum affair. Most plants only exist thanks to partnerships with fungal filaments in the soil which mobilise essential nutrients for them and receive sugars made from sunlight in exchange. Without those partnerships, humans and most other land animals which depend on plants either directly or at one or two removes would not exist. Cooperation gives rise to a living world that is vastly more complex, productive and beautiful than the sum of its parts. An understanding of this reality is one of the key insights of an ecological worldview; and, argues Robin Wall Kimmerer in this short and charming book, it is of vital