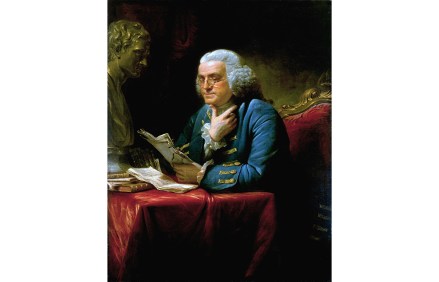

Being a printer was what Benjamin Franklin prided himself on most

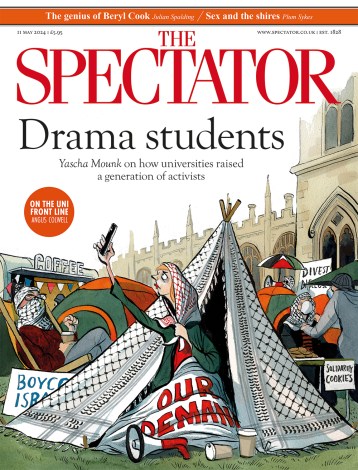

For some readers this book will have the charm of the Antiques Roadshow. Adam Smyth, professor of English Literature and the History of the Book at Balliol College, Oxford, presents with caressing attention to technical detail an array of illustrious book people. They may be unfamiliar names to those who don’t know a colophon from a cauliflower, but he makes his characters wholly accessible. Smyth evidently chose the Bodley Head as his publisher for its connection with the Bodleian Library, in whose rare-books room he researches. As importantly, the Bodley Head was founded with a dedication to fine antiquarian books. The Book-Makers breathes bibliophilia. It recalls Walter Benjamin’s essay ‘Unpacking