Nijinsky, by Lucy Moore – review

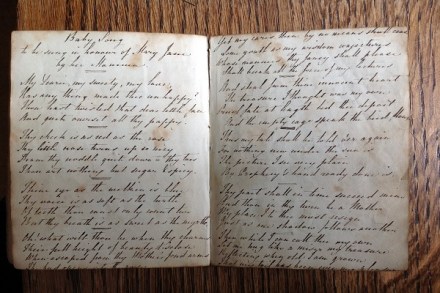

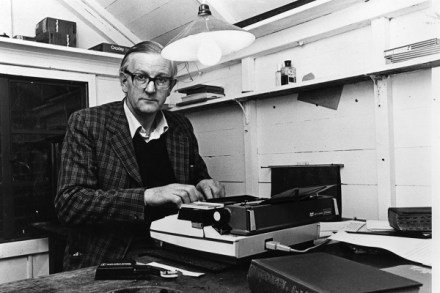

The first biography of Vaslav Nijinsky, which appeared in 1934, was written by his wife Romola with the help of two ghosts — the young Lincoln Kirstein and Little Blue Bird, an obliging spirit called up by a psychic medium to provide information from beyond the grave. Needless to say, the book wasn’t entirely accurate; and nor, two years later, was her edition of Nijinsky’s confessional diaries, a stream-of-consciousness record of his descent into madness, which she censored, restructured and cut by over a third. It took Richard Buckle’s now classic life of the dancer (published in l971 and amended after Romola’s death) to sort fact from fiction and recreate