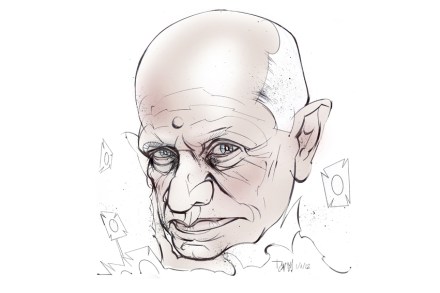

Bookends: A shaggy beast of a book

Autobiography is a tricky genre to get right, which may be why so many well-known people keep having another go at it. By my reckoning Tales from an Actor’s Life (Robson Press, £14.99) is Steven Berkoff’s third volume of autobiographical writings, although I might have missed one or two others along the way. This one, though, is a little out of the ordinary. Written in the third person — he refers throughout to ‘the young actor’ — it tells a number of stories of his formative years ‘in the business’, of auditions failed, of rep tours endured, of disastrous productions walked out of, and of lessons learned, usually far too