The glamour of grime: revisionist westerns of the 1970s

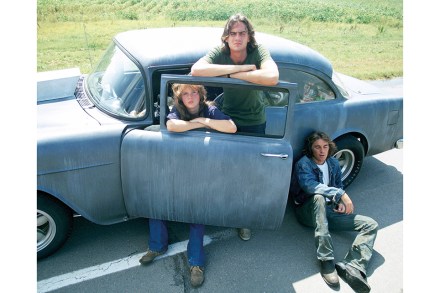

In 1967, the unexpected worldwide success of Bonnie and Clyde blindsided the Hollywood film industry, which then spent the next half decade attempting to adapt to the changing tastes of the new youth audience it had apparently captured. No matter that the picture took a pair of vicious, sociopathic thrill-killers who in real life were about as appealing as the Manson family and reinvented them as glamorous Robin Hood figures, there was obviously money to be made, and the studios wanted a slice of it. The road movies of the 1960s and 1970s were often modern-day westerns in disguise While Peter Biskind’s 1998 study of the late 1960s and 1970s