The odd couple

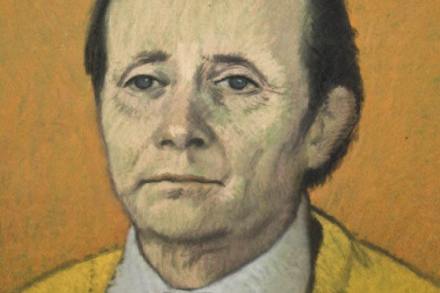

Some years ago now I bought from the artist Robert Buhler a pastel portrait of the composer Lennox Berkeley (reproduced above). Since I knew neither of the two men well (although in the case of each I admired the work without having an irresistible enthusiasm for it), even today people often ask me why I made the purchase. The answer is that in that one work Buhler shows so much more than his usual blithe accomplishment; he is perfect not merely in his portrayal of his sitter’s outward features but also in conveying an inner character of brooding spirituality. Tony Scotland’s book performs the same feat. He miraculously catches a