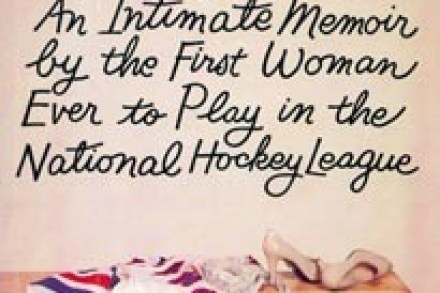

Surprising literary ventures | 15 December 2007

Who is Cleo Birdwell?’ begins the flyleaf text of this book. ‘The simple answer is that she’s a New York Ranger, a schoolteacher’s daughter from Badger, Ohio, who becomes the hottest thing in hockey.’ Well, not quite. The simplest answer is that she’s Don DeLillo, author of White Noise, Underworld and Falling Man, publishing pseudonymously early in his career. Amazons is a woman’s first-person confessional account written covertly by a man. Not content to stop there, DeLillo makes this a book almost entirely about sex (there is very little hockey in it). Every ten pages is a new sexual encounter in which the characters go at it rather in the