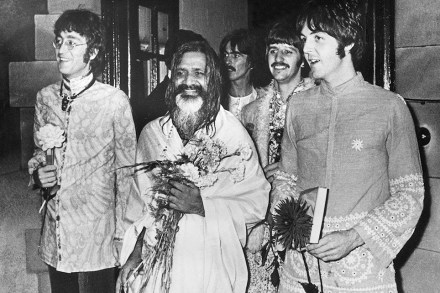

The phoney mystics who fooled the West

In recent years when we’ve talked about the relations between India and the West, we’ve gone back to stressing the impossibility of interchange. A hundred years ago, E.M. Forster ended A Passage to India with the certainty that Aziz and Fielding could not be friends. Forster thought things would be different after Indian independence, but the spectres of cultural appropriation and the assertion of ongoing imperialist guilt have discouraged equal exchange. Meher’s spiritual energy was soon devoted to persuading Hollywood to make a massive movie about his life That may explain why the excellent story Mick Brown tells in The Nirvana Express has hardly been covered in the past. How