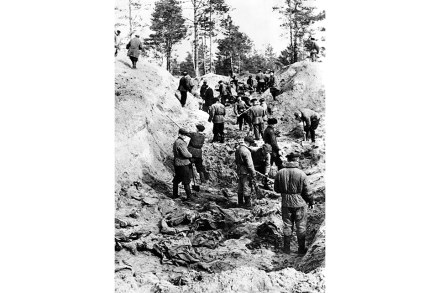

Lies about the Katyn massacre added insult to the horror

On 5 March 1940, as the USSR stamped its authority on a Poland it had partitioned with Hitler, Stalin signed a decree to murder 14,700 Polish officers in the woods by Katyn. These ‘hardened, irremediable enemies of Soviet power’ were not informed of their sentence and simply shot in the back of the head, a form of execution favoured by the secret police, the NKVD, for whom this method was just part of bureaucratic procedure. NKVD forgers changed the dates on the documents found in the dead officers’ pockets at Katyn When the Nazis turned on the Soviets in 1941 and marched east, they found the mass grave. Goebbels was