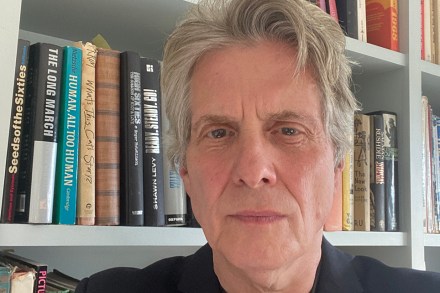

Blake Morrison mourns the sister he lost to alcoholism

Blake Morrison’s previous memoirsAnd When Did You Last See Your Father? (1993) and Things My Mother Never Told Me (2002) examined his parents with the clear-eyed appraisal that only adulthood brings. In the first, he evoked the vigour of his father, Arthur: his sense of fun when rule-breaking for thrills, and the selfish entitlement which allowed him to follow his whims, oblivious of the feelings of others. The contrast between his energy when fit and his frailty when ill were stark – a dichotomy many face when a beloved parent ages and dies. The second memoir examined the life of his mother, Kim, who, like Arthur, was a doctor, but