Joy, fear and regret in contemporary Britain

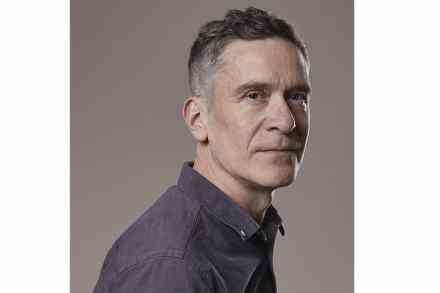

For two and a half years, as Britain adjusted from normality to the most disorienting collective trauma of our lifetimes, Will Ashon trawled the country for strangers’ stories. He wrote letters to random addresses, went hitchhiking, talked to the drivers and followed chance connections in pursuit of glimpses into other people’s lives. Once they had consented to speak, he asked some to tell him a secret and others to answer a question from a list. The resulting anonymous confessions, reminiscences, philosophical reflections and anecdotes were obtained via interviews, emails or voice recordings. They form a quietly remarkable study of the state of the nation, in which fragments piece together into