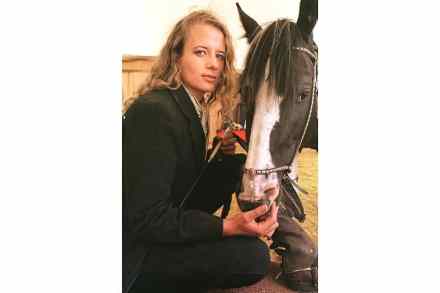

Sister, where are you? – Clover Stroud mourns her beloved sibling

‘CERTIFICATE IS NOT EVIDENCE OF IDENTITY,’ the freshly issued death certificate read. In the craziness and shock of grief for her beloved sister Nell Gifford, who died at 4.20 p.m. on 8 December 2019, aged 46 (‘Cause of death: metastatic breast cancer’), Clover Stroud found herself clinging to those capitalised words. ‘Yes, the certificate was wrong… My sister was not the deceased and the very certificate I was holding was telling me that.’ She started searching for her everywhere. ‘Whereareyouwherareyouwhere-areyouwhereareyou’ she asks for one whole page of this book in an enlarged typeface denoting the din in her head. She feels as if she’s setting out into the evil depths