For the Time Being

Time slips away while we conjecture how to make best use of it. Waking late, the hours already sliding by, the day unplanned and shrinking. We’ll fill the time, anaesthetise the loss, The final hour will come and it will pass.

Time slips away while we conjecture how to make best use of it. Waking late, the hours already sliding by, the day unplanned and shrinking. We’ll fill the time, anaesthetise the loss, The final hour will come and it will pass.

On YouTube there’s a brief dance video of a Viennese waltz so enchanting that not even Fred and Ginger in ‘Cheek to Cheek’ can outcharm it. A dandy in top hat and a captivatingly pretty girl in bonnet and white frills do ecstatic jumps and twirls in each other’s arms to the seething Rosenkavalier waltz.

It’s rare that granitic and iron-jawed prose is also enveloping and warm, but that’s just one of the many enticing literary paradoxes in the American writer John Ehle’s 1964 novel The Land Breakers. The work was the first of seven volumes that Ehle dubbed his ‘mountain novels’, books which today tend to get tagged as

Locate. Stalk. Encounter. Rush. Chase. The pace of Sarah Hall’s fifth novel follows the five stages of a wolf hunt as she imagines a pack of apex predators restored to the British countryside: the thrill of lean, grey flanks streaking through the bracken sending vital adrenalin coursing through an ecosystem grown sluggish. Her fiction is

The public schools ought to have gone out of business long ago. The Education Act of 1944, which promised ‘state-aided education of a rapidly improving quality for nothing or next to nothing’, seemed to herald, as the headmaster of Winchester cautioned, the end of fee-paying. Two decades later Roy Hattersley warned the Headmasters’ Conference to

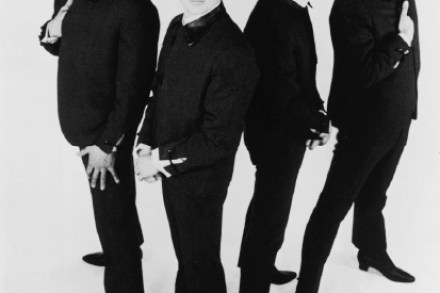

As Johnny Rogan notes in this new biography of Ray Davies and the Kinks, it is almost 50 years since the term ‘Swinging London’ was first used by a newspaper to describe ‘the most exciting city in the world … all vibrating with youth’. Those smashing times may not have lasted long but the vibrations

John Hemming is our greatest living scholar-explorer. He is best known for his extraordinary first book The Conquest of the Incas, published in 1970 when he was 35 — a work of vivid, monumental scholarship that is still unsurpassed. His love for the peoples of the Amazon produced a remarkable historical trilogy: Red Gold (1978),

Before I read this book about vitamins, I thought I knew what it would be like. It would be vaguely reassuring. It would tell me that I was consuming the right vitamins, but perhaps in the wrong quantities. Medically speaking, I expected it to point me in a certain direction. There would be chapters about

The most successful newspapers have a distinct personality of their own with which their readers connect. In Britain, the Daily Mail and the Guardian are perhaps the best examplars of that. In Ireland, the decent, if slightly smug, denizens of Dublin 4 know exactly where they are with the Irish Times, and that it will

No, let’s not look at the old photographs any more: our hair was so full and shiny then, and anyway we can’t tell all those babies apart now. And who was the woman in the lace blouse sitting on our sofa, with that basilisk stare? I don’t remember ever seeing her before. Let’s put the

Patrick Gale’s first historical novel is inspired by a non-story, a gap in his own family record. His great-grandfather Harry Cane spent the first part of his life as a gentleman of leisure among the Edwardian comforts of Twickenham. What then suddenly prompted him to abandon his wife and small daughter and emigrate to the

Julian is clever, handsome and spoiled, a gilded youth who has all the girls wanting to mother him, and a mother who wants to mother him even more than they do. Part of his appealing vulnerability is that he has no father; another part is that he has a potentially fatal allergy to wasps. One

They lived in barrels, they camped on top of columns, or in caves: the lives of the sages are often inconceivable to the modern reader. Seneca, however, that rich, compromised sophisticate of the first century AD, is instantly kin, his voice weary with consumerism, his problems definitively first-world. ‘Being poor is not having too little,’

My father was always arguing and falling out with people in the neighbourhood, but when he clashed with Mister Jones, our friendly, cheerful greengrocer, I remember my brother shouting in dismay, ‘Oh not Mister Jones as well!’

Early in the second section of Aatish Taseer’s The Way Things Were we are presented with a striking description of Delhi. The city’s bright bazaars and bald communal gardens, among them ‘the occasional tomb of a forgotten medieval official’, are ‘stitched together with the radial sprawl of Lutyens’s city’. Taseer acknowledges the landscape’s beauty, but

In a 2008 essay Zadie Smith held up Tom McCarthy’s austere debut Remainder as a bold exemplar of avant-garde fiction, comparing it favourably to Joseph O’Neill’s lush Netherland, which she deprecated as incarnating the worst delusions of realism. Funny how rapidly Smith’s distinction has disintegrated: McCarthy’s latest, Satin Island, bears an uncanny similarity to O’Neill’s

In recent years there has been a fashion for so-called ‘new nature writing’, where the works are invariably heavy with emotion, while the descriptions of place and wildlife often serve as a hazy green backcloth against which the author depicts the main subject —their own personalities. It comes as something of a shock, therefore, to

With the odd exception — I think principally of Charles Moore’s life of Margaret Thatcher — the genre of political biography has known hard times lately. There are few faster routes to the remainder shop, other, of course, than the political memoir, most of which I presume are now written to create a tax loss

Jeremy Clarkson has been getting it in the neck from Twitter’s (I was going to say) tricoteuses — but social media is both thicko mob and gleeful, literal-minded public executioner. A couple of weeks ago it was George Galloway; and the week before that — oh, I can’t remember. I had a theory about 21st-century

Los Angeles ghetto life — thrashed, twisted and black — is not a world that most Americans care to visit. Black Angelinos can be — and for a period in the 1980s and early 1990s, were — murdered for a trifle. The slightest act of ‘disrespect’ may call for a tit-for-tat killing, where an entire