-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

BBC snap up GB News alumnus

Is the BBC trying to mend its ways? Word reaches Mr S that John McAndrew – the former head honcho of GB News – is returning to Broadcasting House as the Corporation’s new Director of News Programmes. The TV veteran boasts more than a quarter of a century of experience in news and current affairs broadcasting, holding senior roles across a smorgasbord of stations including the Beeb, Sky, ITN and NBC.

McAndrew was also the first Editorial Director and Director of Programming at GB News, but left after less than a month following the suspension of presenter Guto Harri for taking the knee live-on air. Since then he’s found a safer berth as the launch editor of the Andrew Neil Show for Channel 4, having previously worked with the former Sunday Times editor on the Daily Politics show in the mid-noughties. McAndrew was also tipped for the top job at BBC News last year; a role which went instead to then-ITN chief exec Deborah Turness, to whom he will now report.

Proof, perhaps, that not all at W1A share a distaste of Britain’s broadcasting upstart?

Will the Tories give Andy Burnham the power to level up?

Are the Conservatives planning to inject Andy Burnham with political steroids? That could be the result of one of the plans being mulled by Chancellor Jeremy Hunt, who has been trying to work out how to make levelling up something that works and lasts.

Greater Manchester Tories will spit tacks about the mayoral position created by their own party

As I reported in the Observer yesterday, Hunt wants to change the current model of areas bidding endlessly for small pots of money here and there to one where the power is decentralised from Whitehall to local elected representatives. The ideal people to do this, of course, would be elected mayors, given that the whole point of setting up these new layers of government was to empower local areas to take their own decisions.

There are, though, some political problems with this approach which any Greater Manchester Tory would be very quick to point out. They will spit tacks about the mayoral position created by their own party when George Osborne was the Chancellor. Back in 2014, Osborne was on the brink of announcing the Greater Manchester Mayor plan alongside his Northern Powerhouse policy. He was warned there and then by 1922 Committee chair and Altrincham MP Graham Brady that it would only benefit Labour and would set up an unaccountable political powerbase, too.

Eight years later, Andy Burnham’s political success in the role is testament to that. As warned, there is no real structure for scrutiny around him though, unlike the London Assembly which holds the Mayor of London to account. Conservatives in the area now complain that transport, health and housing have not improved at all under Burnham’s watch, but they have precious little opportunity to point this out formally.

Mind you, you could make the same argument about transport, health and housing nationally under the Conservatives in central government. But the logic behind making levelling up something mayors are responsible for delivering is that it is then baked into the system in a way that another government would find harder to remove or ignore.

Labour’s basic position on levelling up is that the government isn’t doing it very well, if at all. But the party isn’t opposed to the concept. Handing levelling up powers to local government would be a way of ensuring it had to sign up to the delivery model, too. This is because a more powerful Andy Burnham would be a problem for a Labour government that wanted to take his new powers and money away.

Britain isn’t ready for onshore wind

Staging rebellions against their own government has become a way of life for many Tory MPs – but why choose onshore wind farms as the hill on which to die? If Rishi Sunak concedes to the demands of a group of (reportedly) around 50 MPs and lifts the moratorium on onshore wind which has been in place for seven years, it won’t take long before we find out why it was imposed in the first place. There are few places in England where you can build a wind farm of any size without either causing serious annoyance to locals or compromising valued landscapes. Most of our lowlands are so densely packed with housing that it is hard to find sites which are not within half a mile of residential properties, while many of our upland areas are national parks or some other designation.

That is why David Cameron’s government hit upon the idea of offshore wind while imposing a moratorium on onshore. The decision transformed public attitudes towards wind power: offshore turbines bother very few people. However, it costs more – the International Energy Agency’s figures for 2020 estimated the average cost of onshore wind, globally, at $50 per MWh and offshore at $88 per MWh. But in Britain’s case, two factors should narrow the gap: high land values and shallow seas. We have large areas off our coasts where the waters are less than 50 feet deep.

In any case, the backbench MP who thinks ever more wind power – of any type – will reduce the cost of electricity and save us from a future energy crisis is fooling themselves. We are only able to absorb current levels of wind power into the grid because it can be balanced with gas-generated power, which can be turned on and off at short notice (albeit at a higher price and lower efficiency than if gas power stations were allowed to run constantly). It works when roughly 40 per cent of our electricity comes from wind and solar and 40 per cent from gas. But if we tried to generate 60 per cent of power from wind and solar? We are about to find out what happens when there is a drop in wind. Over the next couple of days, high pressure will impact the weather over Britain, bringing with it light winds. Combined with less power available to be imported from France, the National Grid has had to announce that it will deploy its emergency winter plan and start paying people not to turn on their washing machines and dishwashers.

Green-minded rebel MPs would be far better off pushing demands for the government to invest in more reliable renewables, including tidal barrages and tidal stream energy – as well as increasing investment in gas. Tidal power may be expensive initially, but will prove a lot cheaper in the long run if it averts the need for more expensive energy storage.

Onshore wind was extremely unpopular last time around (at least with residents in the areas in which it was proposed – it was a lot more popular with landowners). It promises to be even less popular this time, given that the size of wind turbines has increased massively since the moratorium was imposed seven years ago. Rebel MPs should leave it well alone.

The Wellcome Collection’s war on itself

If you, like me, have an unhealthy taste for depressing news, then you’ll have already heard about the Wellcome Collection’s decision to close its Medicine Man exhibition last weekend. The display, which featured an extraordinary range of unusual medical artefacts collected by the entrepreneur Henry Wellcome (1853-1936), has been permanently shut on the grounds that it ‘perpetuated’ sexist, racist and ableist myths, and failed to tell the stories of the historically marginalised. The decision has been cheered on by precisely nobody – both left and right, from what I can see, believe the decision will do nothing to make the world a better place. All it represents is yet another lost opportunity to learn (for free!) about our collective past – including, indeed, its many evils. So what exactly is the Wellcome Collection doing?

The Twitter thread in which the Collection announced its decision, a mere 48 hours before closing the display, offers a few clues. The museum, the thread explains, has long attempted to ‘give voice to the narratives and lived experiences of those who have been silenced, erased and ignored’ – by ‘using artist interventions’. But despite these, it says, the exhibition has only ever really succeeded in telling the story ‘of a man with enormous wealth, power and privilege’.

This can be interpreted in one of two ways. The first is that the museum simply didn’t do its job properly. It attempted to provide some historical context and discuss the experiences of those who might have been overlooked or exploited along the way (as it should), but ultimately failed, with people still somehow coming away with the impression that the exhibition was really just all about Henry Wellcome himself. The second, which I suspect is more likely, is that the curators genuinely think that no amount of commentary or context can ever possibly counteract the implicit message: that by displaying Wellcome’s collection, we’re tacitly condoning everything he ever did and stood for.

This is a very strange view, and one based on an especially garbled kind of Freudian thinking: not just that there are ‘hidden’ messages to be found in everything that we say and do, but that these will always have more of an effect on others than what we say explicitly. In other words, the curators seem genuinely to believe that what visitors learn at a conscious level – like uncomfortable stories about historic injustices – ultimately matter less than whatever coded messages they pick up from the basic fact that the exhibition exists in the first place. By this logic, the display must inevitably be a net negative for society, and should, therefore, be binned.

It’s an absurd argument, and one that, if it were taken to its logical conclusion, would require the abolition of all our museums – not to mention concert halls, libraries, galleries, and universities. But it’s founded on an assumption that runs surprisingly deep in many of our cultural institutions: that even well-intentioned, surface-level deeds are almost always really just masquerades for power. What really matters are all the subtle, unconscious biases secretly driving things underneath.

Is shutting down Medicine Man really what ‘progress’ looks like?

I’m all for a bit of soul-searching. But it’s very difficult to translate this kind of relentless mistrust of ourselves into anything positive. If what we say out loud ultimately counts for less than the things we unwittingly imply, we might as well all just sew up our mouths for eternity. If our good deeds are really just fronts for the unconscious evils secretly motivating us, we might as well stop trying to do anything useful at all. We should simply give in and accept Foucault’s famous dictum: ‘I think that to imagine another system is to extend our participation in our current system.’

Foucault himself was a vastly more impressive thinker than this unfortunate quote suggests – but today, a great many people seem to have taken it quite literally. It’s hard to know whether the team at the Wellcome Collection is among them, but the Twitter statement they produced was notable for its lack of any kind of positive vision for the future. No case was made, indeed, even for what should take the place of the terminated display – only the vague assertion that the museum needs somehow to ‘do better’.

And this is part of what’s so disappointing about the whole thing: just how uninspiring – and uninspired – it is. Closing the Medicine Man display is, supposedly, an urgent moral cause, a moment of great historical reckoning – and yet the Wellcome Collection can’t seem to write about it using anything other than the laziest of stock phrases, euphemisms, and management-speak. The sins of our forebears weren’t evil, they were ‘problematic’. People’s ‘lived experiences’ were ‘erased’. The exhibition ‘perpetuated’ tropes. If this is moral progress, it looks remarkably like a bureaucrat trying to figure out how to sound virtuous without saying anything of substance at all.

Which has led some critics to wonder: is the Wellcome Collection really driven by an ideological mission, or is it simply a stab at trendy progressivism? It’s hard to say. But that it should be so difficult to tell apart today’s supposedly radical politics from bureaucratic, managed decline only shows how insipid and negative the former has become.

This shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone who’s followed what Christopher Lasch once called the ‘improbable alliance of psychoanalysis and cultural radicalism’. In 1981, he wrote:

Freud puts more stress on human limitations than on human potential, he has no faith in social progress, and he insists that civilisation is founded on repression. There isn’t much here… that would commend itself to reformers or revolutionaries.

The assumption that subterranean purity matters more than our outward deeds will always prove a political dead end, producing no ultimate vision of the Good of its own.

So is shutting down Medicine Man really what ‘progress’ looks like? Is this the great, utopian vision of the future we’re fighting for? The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends, apparently, towards the shrinking of our public institutions: the closure of free exhibitions, the sacrifice of accumulated knowledge and the undermining of historical wisdom.

At the end of the Wellcome Collection’s thread comes a final request: ‘We want to do better. And we invite you to help us get there. Tell us: what’s the point of museums?’ Here’s an answer. Museums are places for the curious, for those with an open-minded attitude to learn. They aren’t supposed to do everything all at once, and that’s just fine.

The Wellcome Collection’s ‘self-reflection’ is no reflection at all: it is rote-learned and bureaucratic. Museums should be anything but.

Where’s the moral outrage at England’s cricket tour of Pakistan?

Everyone on the television agrees: seeing an England team give succour to a repressive regime by playing prestigious fixtures on its soil is deeply troubling – or ‘problematic’ to use the latest horrible buzz word. A society that represses gay people and women and whose ruling class routinely engages in corruption to further its own interests should not be ‘normalised’ via world-class international sport, runs the argument.

But all these conditions apply in Pakistan just as they do in Qatar. Yet has anyone heard a squeak of broadcast media complaint about the England cricket team’s tour of that country?

Far from agonising about whether to take a knee, wear a rainbow armband, boycott the country altogether or engage in some other novel protest, our cricketers were pictured this weekend happily ambling through Benazir Bhutto International Airport in Rawalpindi to start their first tour of Pakistan since 2005. The official England Cricket twitter feed proudly shared the footage, declaring: ‘Touchdown in Pakistan for our men’s test squad!’

To have England arriving for a test series is a huge coup for the Pakistani government (pun intended)

Why the double standard? Of course, it could fairly be argued that a cricket test series is nothing like the football World Cup in terms of its global impact and reach.

But in Pakistan cricket is a sporting religion and the recent scarcity of international touring teams – largely due to the threat of Islamist terror attacks – has been deeply felt. To have England, where the game was born, arriving for a test series is a huge coup for the Pakistani government (pun intended). If it is unable to ensure the population has bread – or basic public services – then at least it can give them the finest of circuses for the next three weeks or so.

Nobody should kid themselves that Pakistan is any less repressive than Qatar, either. The UK government’s own official assessment warns that provisions in the Pakistan Penal Code ‘suggest that any same-sex sexual acts that involve penetration could be prosecuted under sharia provisions and may be punished by death’.

Women’s rights are in practice repressed with equal ferocity, despite some constitutional protections, with a US State Department report of 2021 noting: ‘The government did not effectively enforce the Women’s Protection Act, which brought the crime of rape under the jurisdiction of criminal rather than Islamic courts.’

If one is going to use the power of sport to spread western societal norms across the globe in true cultural imperialist style, then a little consistency would be appreciated. There is no logical reason why our nation’s footballers should be expected – or should expect themselves – to become roving social justice warriors when the same expectation is not applied to our cricketers.

One suspects that the biggest reason for media hesitancy in holding Pakistani society to the same standards it applies to Qatari society is more prosaic. The size of Britain’s Pakistani-heritage population is estimated to be well over a million and there would be uproar among it if such a thing were to be done. Our broadcasters simply don’t have the bottle to do it.

But the most noxious aspect of British liberal inconsistency when it comes to human rights in Islamic societies – which is what we are talking about – is surely the absurdity of protesting far more zealously against the application of Islamic standards in Muslim countries than against the spread of those same Islamic standards in western countries, such as our own. A Gary Lineker half-time sermon against that is not something we are ever likely to hear.

Matt Hancock showed how Conservatives can win

It’s somehow appropriate that Matt Hancock finished third in the 2022 series of I’m A Celebrity … Get Me Out Of Here! Third is a word that fits him neatly. Third choice. Third wheel. Third rate. Third is the ‘and you did great, too!’ of victories. The day before, Hancock had donned the brass hot pants of ‘the Bronze Bronco’ for the annual Cyclone challenge, as if bottom rung on the podium already belonged to him.

His continued presence in the jungle – as straightforward, likeable contestants such as Charlene White and Mike Tindall, and less affable ‘characters’ like Boy George and Chris Moyles fell by the wayside – had started to rattle some of the commentariat. To be fair, these people are already fairly rattled on a good day. The comedian Emma Kennedy, who has been transformed by social media from personable supporting player to panicky crank, became convinced yesterday that a dark conspiracy was afoot by Hancock’s PR agent and a ‘betting syndicate’ to see Hancock grasp the crown of Jungle King by nefarious means. TikTok was involved in this apparently, somehow. Emily Thornberry started spreading this conspiracy too, which will have done the coffers of ITV no harm at all. It’s especially odd as Kennedy at least must know that all celebrities on reality shows have PR people trying to big up their clients, and that this tactic never works.

There was a flavour of the Leave vote and the 2017 general election about Hancock staying in, night after night

It was also plainly evident that Hancock could not win, and likely not make the final two. He was up against two exceptionally well-adjusted and likeable people in Jill Scott and Owen Warner – young, uncomplaining, funny, game for anything, every parent’s dream kids. In fact, the kind of people who nearly always win such competitions. The loss of Tindall at the last hurdle almost guaranteed Scott’s win, as the single transferable votes of his supporters was never likely to transfer to Hancock.

But Hancock has won a different prize. The announcement that he was joining the jungle was one of those things that’s simultaneously a big surprise and makes you roll your eyes and say ‘oh, of course he is’. Lack of judgement and clumsy self-promotion are what his PR could justly claim are the brand values of Matt Hancock.

The bigger surprise, of the genuinely unforeseeable kind, came as the tasks and challenges of the jungle unfolded. Hancock’s high levels of emotional coolness, his physical competence and determination, were a revelation. Seeming to be one thing – weedy, clumsy, gauche – but turning out to be another is surely a factor in the public popularity that saw him sail through to the final after the initial first few days of being fed to snakes, buried alive, etc. There was none of the expected catharsis for the public in Hancock insouciantly chowing down on camel’s vagina. Not a hint of ‘oho, now he’s suffering!’ We soon tired of it and turned our eyes on Moyles and Boy George.

On the immediate practical level, in a survival situation (or as much as you can get of one in a TV game show format) Hancock, with his blithe physicality and level head, bringing back stars and thus food for his campmates, proved to be useful. And that was something nobody, in the jungle or watching the jungle, expected.

I noticed my opinion of him reverting the moment he crossed the rope bridge for his exit interview with Ant and Dec. Away from any imperative need for those qualities, back in our technological world of plenty, he was instantly just bloody Matt Hancock again, irritating little man, cheat and ‘love rat’, overpromoted and banal, who thinks he is something extremely special. The kind of politician who could invent, with a straight face, their own personally branded app. His immediate public groping of his paramour brought it all back – the over enthusiastic tonguing of the nerdy teenage boy at the school disco displaying that he is one of the alpha lads, after all.

But there’s a bigger lesson to be learnt from Hancock’s surprising survival to the final, and that lesson is about the sheer bloody-mindedness of the British public. We hate being taken for mugs, but we hate being taken for granted even more. There was a flavour of the Leave vote and the 2017 general election about Hancock staying in, night after night; another demonstration of the public pushing back when their compliance is assumed.

If a narrative is set, the temptation to throw a spanner into its works is very strong. This is one of the reasons why I think the Conservatives might still, just possibly, scrape a majority at the next election, particularly when the alternative looks more or less the same. There is nothing of Jill Scott or Owen Warner in Keir Starmer or any of his front bench. We’d do well to keep that in mind.

Lying-in-State leaves its mark on parliament

The Lying-in-State of Her Majesty the Queen was widely hailed in September as a triumph. The organisation was slick, the tributes were moving, the crowds respectful and the queue deftly managed. But it seems that the otherwise flawless ceremony had one misstep: the impact of all those thousands of visitors on the floor of Westminster Hall, the oldest remaining part of the original Palace of Westminster.

Steerpike hears whispers of discontent among the House authorities about the management of the 180 year-old Yorkstone floor during the recent Lying-in-State. To allow for an estimated 250,000 mourners, a carpet was glued down onto Westminster Hall’s floor to lessen the impact of all that continuous footfall. And now some fear it has left permanent damage in the ancient structure. A House of Lords spokesperson told Mr S:

As a consequence of the high-level continuous footfall through Westminster Hall during the lying-in-state some delamination to the Yorkstone floor has occurred. It has exposed some areas of bare stone that will blend in with the surrounding areas over time. This does not present a structural risk.

Let’s hope that’s all there is to it…

Can Sunak get a grip on his party?

As Tory MPs ponder whether to stand down at the next election in the face of grim polling, the Prime Minister is facing an uphill task to show he has a grip on his party. Ahead of a difficult winter with the NHS and public sector strikes, Rishi Sunak is facing a two pronged rebellion on the levelling up bill. Theresa Villiers is leading blue wall rebels against mandatory housing targets and Simon Clarke is railing against the ban on new onshore wind farms. Meanwhile, there are concerns in government that more MPs could announce this week that they plan not to seek-re-election, with the deadline to tell CCHQ 5th December.

The public and MPs are still forming their view of the new prime minister

When it comes to the rebellions, it’s Clarke’s that currently has the most momentum behind it. The former levelling up secretary is thought not just to be supported by former prime ministers in the form of Boris Johnson and Liz Truss – but also many MPs who served under Truss. Former party chairman Jake Berry is the latest to signal his support. It is adding to concerns in government that there is a rebel alliance forming of former ministers with scores to settle.

On this morning’s media round, business secretary Grant Shapps appeared to hint that a climbdown could be coming – telling Times Radio of the rebellion: ‘It’s not really a row, we are basically saying the same thing, you need local consent’. Levelling Up secretary Michael Gove is set to meet with rebels on both sides as the government attempts to quell the rebellions.

Is this all such a problem for Sunak? Compared to the high drama of the past few months which saw the party oust not one but two leaders, a Commons rebellion on planning looks rather tame. However, the public and MPs are still forming their view of the new prime minister. It means that Sunak is under pressure to show that he can command authority of his divided party.

It’s no coincidence that Labour want to depict Sunak as a weak leader. Sunak is leading Starmer in polling on the question of who would make the best prime minister. The opposition hope to show that the parliamentary party is so divided that who ever leads it will face problems – thereby painting Labour as the stable alternative. Sunak still has time to set out his stall – tonight he will speak at the Lord Mayor’s Banquet on foreign policy. But he is currently at risk of looking as though he is led by events as opposed to being a leader with an agenda of his own.

Why ‘Uber for the countryside’ is a great idea

The disappearance of rural bus routes is one of the small tragedies of our time. It isn’t, alas, a very glamorous tragedy. It affects older people, poorer people, people who live in unfashionable parts of the country. You seldom see Twitter storms about rural bus routes. You don’t see footballers campaigning on the issue with moist eye, bent knee and clenched fist. Those awkward one-deck buses, trundling from village to village, debouching the odd person here and there at an unloved bus stop on a drizzly rural B-road: they will never occasion so plangently romantic an elegy as Flanders and Swann’s ‘The Slow Train’, which lamented in the 1960s the equivalent decline of the railways.

But small tragedy it is. Rural bus routes are part of the network of capillaries that keep small communities alive, that bring just enough custom to keep the village pub or the local post office going. They help people who don’t have access to cars to get to work, to visit the doctor or – a good never measurable on official statistics – to visit one another. They have, one by one, been closed down or cut back in the name of efficiency. They are, local government has tended to conclude, just too expensive and serve too few people to sustain.

But here’s the cheering bit. The Department for Transport has had a quiet, clever, modestly priced and – it seems to me – entirely good idea for how to replace them. All credit to Boris Johnson’s 2021 National Bus Strategy. Local councils – backed by £50 million of government money – are launching what they call ‘Uber for the countryside’: a network of minibuses that can be hailed with a smartphone app and will pick passengers up and drop them exactly where they want to go, diverting here and there to pick up another passenger if the app’s algorithm decides it can be done without intolerable disruption of the original journey.

If this service will drop its users door to door at no significantly greater cost than a bus ticket, that is a small miracle

It’s not perfect, of course. Not everyone who’d benefit from this has a smartphone and the savvy to use an app. But it’s surely a bus ride in the right direction. If, as claimed, this will drop its users door to door at no significantly greater cost than a bus ticket, that is a small miracle – not least for those who don’t live near a bus stop or have physical disabilities that make walking to one a challenge. And no doubt, for those who mind about these things, it’s better for the environment than vast, expensive, empty charabancs on their fixed routes. Imagine if this could, managed sensibly, bring a whole new lease of life to rural businesses and countryside existences.

The problem with state funded projects, as people on the right correctly complain, is that they tend to be one-size fits all. Central government finds it hard to be nimble, to localise, to distribute resources efficiently, and so on. State spending is that 40-passenger bus chugging down a country lane four times a day in each direction with a solitary cider-drinking teenager aboard. As Milton Friedman argued, if you’re spending other people’s money on other people (which is most public spending) you don’t much care how much of it you spend and you don’t much care what you get in return.

The solution that’s usually offered from that quarter is that you wheel in private companies to help, in the hopes that competition and free enterprise will produce efficiencies and innovations unavailable to the dead hand of the state. Attractive to governments, who have someone else to blame; attractive to the companies involved, who are hard to remove once in place no matter how terribly they perform or how deeply they gouge the public purse on prices.

The problem with this, as people on the left just as correctly complain, is that in practice the vaunted efficiencies of the market tend to be directed not towards getting the best value, but towards extracting as much profit as possible. This type of spending perhaps falls into the category Friedman identified as ‘spending other people’s money on yourself’. That’s how you end up paying more to keep a child in a care home than to send it to Eton, or with agency nurses costing more than lawyers, or with Baroness Mone getting even richer.

But here, in ‘Uber for the countryside’, is the best of both worlds. Here is a stone-cold instance of a public service learning from the private sector and the lesson, for once, not being ‘somebody needs to be making a profit out of this’. That is very heartening: not the sort of ‘efficiencies’ whose vague invocation presages a swathe of lay-offs and corner-cuttings, but actual efficiency of a measurable, visible sort.

There are all sorts of unattractive things about Uber, I know. It has been criticised for turning the screw on its drivers in all sorts of ways, and for a business model that seems geared to the grand tradition of establishing a near-monopoly by predatory pricing before cranking up the fees at its leisure. It flourished under a boorish tech-bro leadership. But those aren’t the qualities that are being imitated here.

The original brilliance of Uber, to which complaints about its business model are quite irrelevant, was the way that it used technology to allocate resources with never-before-seen efficiency. Instead of having to have a vast fleet of black cabs circulating a metropolis so that, on average, you’d be able to hail one tolerably soon wherever you were standing, you could get the same outcome with a far smaller fleet. Uber was able to send the taxi three streets away right to the kerbside. And it could do clever things like knocking a bit off the cost if you picked up another passenger on the way. It was, in programming terms, an elegant computational solution to a problem that had previously only been susceptible to brute-force solutions.

Whoever thought that this might be applied to rural transport for the public good, and studiously did the sums, and lent their labour to an area of policy that won’t spark a hashtag campaign but might save money and vastly improve lives…well. They may not earn a Flanders and Swann song, but I hope they get five-star reviews on the app.

America is entering a golden age of democratic capitalism

America could be entering the ‘Great Stagflation’, defined by economist Noriel Roubini as ‘an era of high inflation, low growth, high debt and the potential for severe recessions’. Certainly, weak growth numbers, declining rates of labour participation and productivity rates falling at the fastest rate in a half century are not harbingers of happy times.

But the coming downturn could prove a boon overall, if Americans make the choices that restore competition and bring production back to the United States and the West. In the United States, the contours of a new post-pandemic economy are becoming clear, particularly in the Sun Belt and parts of the heartland. That revival could result in an economy that is stronger, more innovative and entrepreneurial.

This is not to say that a recession wouldn’t be hard, particularly for groups like millennials, blue-collar workers and immigrants who have already suffered through the 2008 recession as well as the pandemic. They have been victims of very poor business and government practices that have created inflation and incentives either not to work or to invest in nonproductive activities. But if the 2008 recession ended with only tepid growth, this time around America may eventually see something different.

The best evidence for the prospect of better times ahead in the United States lies in the post-pandemic increases in the formation of new businesses, in 2020 up to 4.4 million applications compared to roughly 3.5 million in 2019. In the first half of 2022, applications including those from non-employer businesses remained up by 44 per cent from before the pandemic. In 2021, applications, including likely employer applications, totalled around 1.8 million by year’s end — almost half a million more than in 2019. According to the Economic Innovation Group, US new-business starts are on course to set a record this year.

The action today, unlike that of the previous decade, is not found so much among finance-backed IPOs, which are suffering their biggest decline in two decades. Instead, small grassroots businesses are seizing new niches, even in service industries, that could transform the American economy. ‘Lots of good things happened during Covid,’ suggests Shaheen Sadeghi, founder of California-based LAB Holdings, which builds ‘anti-malls’ hosting local businesses. ‘The mediocrities went under, but the people who survived are doing better than ever before. They created new ways of doing business that fit the new realities.’

This grassroots growth is very different from what happened after the last serious recession in 2008. Once the financial engineers of the City and Wall Street finished demolishing the economy, governments moved to bless more consolidation.

The big banks recovered gloriously as inequality in the States soared and incomes, particularly for minorities like African Americans, sank. As one conservative economist put it in 2018, ‘The economic legacy of the last decade is excessive corporate consolidation and a massive transfer of wealth to the top 1 per cent from the middle class.’ Fortunately, entrepreneurialism remains embedded in America’s national DNA. In more managed societies — like Germany, Japan or France — the leading companies tend to remain the same over time; even those historically connected to fascism, such as Mercedes, Krupp and Mitsubishi, survived their ignominy and remain dominant. But in the United States disruptive change has been the norm: only fifty-three of the current Fortune 500 companies were there in 1955.

This emerging new economy is also reshaping US economic geography. Sadeghi’s LAB (‘Little American Business’) has developed nearly fifty projects for small, independent firms, predominantly in suburban settings, places not usually thought of as sources of cultural and business innovation. By contrast, the massive bailouts standard for the last three years have not slowed the movement of people and companies away from dense, often hyper progressive urban locales, dispersing people and work to their periphery.

This is a marked change from the last recession. The great financial crisis of 2008, precipitated by the bursting of a housing bubble, led to much speculation in America that Sun Belt suburbia would become what the Atlantic predicted would be ‘the next slums’, and that city living would make a comeback. To be sure, the oligarchic nature of the recovery was somewhat less damaging to cities like New York, San Francisco and Boston, where financial and tech firms are concentrated and key managerial talent remained, despite its previous malfeasance.

This new wave of industrial development could be transformative, bringing new wealth and opportunities to left-behind areas

Yet the ongoing exodus from big urban centres started before Covid, with over 90 per cent of all metropolitan growth between 2010 and 2020 in the suburbs and exurbs. The 2020 census notes that four of the five US counties gaining at least 300,000 people were in Texas, Arizona or Nevada. Houston and Dallas added far more people than New York, Chicago, Los Angeles or the Bay Area.

The pandemic, and the rise of online work, seem likely to accelerate this movement. The big blue coastal cities have all experienced meagre growth and, since 2020, serious population losses. In the last year, the biggest migration losses took place in three key states: New York, New Jersey and Illinois. In the post-pandemic economy where some 30 per cent of the employed expect to work mostly remotely, this turns even small towns into new centres of economic dynamism.

Overall, notes demographer Wendell Cox, offices on the fringe have recovered far faster than those in the largest urban cores. According to Jay Gardner, president of Site Selectors Guild, leading US companies are looking increasingly at opportunities in smaller cities and even rural locations. The biggest upsurge in new business formation took place in the Deep South, Texas and the southwest while New York and the West Coast lagged. This year, Zen Business found that the best places for small businesses — in terms of taxes, survivability and regulation — were overwhelmingly in the south, parts of the Great Plains, Utah and the Midwest.

One surprising aspect of the emerging American economy reflects tentative steps by corporations to return production to the United States. The ‘reshoring’ movement has been building over the last several years, helped by the boom in shale oil and gas, which makes US manufacturing more efficient. But the return became imperative when China blocked healthcare exports during the worst days of the pandemic. America’s painful dependence — even for military goods — on its primary global adversary is starting to concentrate minds.

Indeed, up to 70 per cent of firms consulted in a March 2020 survey said they were likely or extremely likely to reshore in the coming years. Camille Farhat, CEO of RTI Surgical, suggests the pandemic is convincing business leaders to stop ‘destroying the supply ecosystem’ that makes production possible. ‘To stay safe, you have to do contingency planning. You have to restore the network and maintain surplus production capacity. Hopefully, we are learning that lesson.’

Returning production to the United States opens new possibilities for more than manufacturing. When firms move production abroad, they often follow by shifting research and development there as well. Now the United States, and the West generally, have a chance not only to relearn the basics of production but to hone and maintain their innovative edge. Critically, there is widespread political agreement on this issue in the States, apart from some libertarian fundamentalists and a few congenital socialists.

The return of production will only enhance the current geographic shift already underway. The new investment tide is far more likely to head to business-friendly, lower-cost states than to those like California, which ranked near the bottom of the table last year for new capital projects. Critically the new surge of chip production — backed by the federal government and once the of the state I’m from — is occurring almost entirely in more flexible states like Ohio, soon to be the site of the world’s largest semiconductor factory. Even the green economy, so passionately embraced on the blue coasts, won’t provide many jobs there. Almost all the new electric vehicle and battery plants are located in the heartland, the south or locations east of the Sierra Nevada. Tesla’s original California plant may soon be the only large-scale ‘green’ factory left in the state.

This new wave of industrial development could be transformative, bringing new wealth and opportunities to left-behind areas. Manufacturing industries attract skilled workers such as engineers and software developers, as well as training and development for the local work force. States like Ohio, Kentucky, Nebraska and Tennessee already have flexible training programs following the successful approaches employed in such places as Germany, Sweden and Denmark.

Of course, even the threat of a recession, much less a strong one, is likely to cause widespread pain. Whether or not that pain is mitigated by new opportunities depends on whether cities, states and the federal government adopt policies that allow Americans’ natural proclivities to thrive. Mean-spiritedness and individualism — which sometimes manifest as determination and perseverance — may not currently be popular with the governing classes, but ambitious restlessness could well prove the best response to disruptive times.

This would necessitate, particularly in America’s great core cities, a turn away from a focus on ‘inclusion’ and environmental righteousness to a regulatory regime that encourages new locally centred growth. This would include ditching policies like rules banning contract work or artificially high minimum wages that suppress start-up growth. Rather than focus only on pleasing large enterprises, and their investors, states and cities need to regard start-ups and fledgling businesses as critical seeds for their own future.

As the downturn worsens, there will be calls to extend the welfare state along Scandinavian lines, comforting for some but unlikely to create a strong post-recession America capable of leading the world economy or competing with China. Nor does the country need to go back to the ruinous consolidation of financial assets that help fund chimeras like WeWork and their performative hypesters, which produce very little real value.

The real heroes of post-pandemic America won’t be the oligarchs, flashy venture-funded promoters or the elite bureaucrats who lorded it over the nation during the pandemic and seek to repeat the performance under the aegis of ‘climate emergency’. Rather than imperious bureaucrats and craven corporate executives, the United States’ future economy depends on those who rent a deserted storefront on Main Street, establish a business from home, or build a new production facility in rural settings or beyond the suburbs. Most will never be celebrated in the press but collectively they represent the hidden power that can move America back toward a dynamic democratic capitalism that the world, particularly the next generation, desperately needs.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s world edition.

The best out-of-print books (and where to buy them)

Those overstuffed shelves of the latest releases aren’t always the best place to start when you’re shopping for a book to read (or to give as a Christmas gift). You can find plenty of out-of-print books with timeless appeal that are worth snapping up – if you know where to look.

Elizabeth von Arnim’s Introduction to Sally, for example, is almost 100 years old, but is a very enjoyable read if you can find a copy. Mr Pinner is a shopkeeper and he and his wife have longed for a child for years, so they are thrilled when their daughter is born. Mr Pinner wants to call her ‘Salvation’ but they compromise on ‘Salvatia’ (shortened to Sally). Sally grows up to be the most beautiful girl anyone has ever seen. She is so good-looking that Mr Pinner realises it is a challenge to protect her from the male gaze. Mrs Pinner dies when Sally is a teenager, and the responsibility of keeping Sally safe falls at Mr Pinner’s feet.

Sally starts working with her father in his shop and the number of customers crossing the threshold increases as everyone wants to get a glimpse of Sally. Mr Pinner decides to move to a rural premises in Cambridgeshire (with a high female population as its main selling point) to protect his daughter. But when she gets an offer of marriage from Jocelyn Luke, a bright and promising student, Mr Pinner is thrilled as he realises that the role of safeguarding Sally can be passed to her husband. Sally’s mother-in-law, however, is appalled at the match. She sees Sally as being beneath their family. She is distressed that her daughter-in-law has poor diction, and she winces every time Sally calls Jocelyn Luke her ‘’usband!’.

First published in 1926 by Macmillan and Co, the book has been out of print for many years. Von Arnim’s earlier titles Elizabeth and her German Garden and The Enchanted April have remained hugely popular, and Introduction to Sally retains the author’s signature sentiment. It is an amusing, farcical story that carries an Austenian sense of humour. Mr Pinner ‘married Mrs Pinner when they were both twenty, and by the time they were both thirty if he had had to do it again he wouldn’t have’. The relationship between Sally and her mother-in-law will also raise a smile. Sally is proud of her background; she is happily working class and she will not be changed.

The same cannot be said for Lady Norah Docker, whose Norah: The Autobiography of Lady Docker tells her incredible life story. It was published in 1969 by W.H. Allen and ghostwritten by showbusiness columnist Don Short, and it is the only authorised book on her life. She married three multi-millionaires (each of whom is assigned a chapter in the book) and held the accolade of being the only person banned from Monte Carlo for bad behaviour when she tore up the Monegasque flag following a dramatic falling-out with Prince and Princess Rainier.

Born above a butcher’s shop in Derby in 1906, Norah had big ambitions when she was young. She moved to London and started work at the Café de Paris before trying to secure a job in retail. Her anecdotes are marvellous: while she was being courted by three men simultaneously two gave her a gift of a diamond wristlet, which proved problematic as she had to remember to wear the correct bracelet with the correct beau.

While a work of non-fiction, the autobiography frequently wanders into the delightful realms of make-believe. If there was ever a book ready for film, this is it

She fell in love with her first husband, Clement Callingham, at the Café de Paris. They had a son called Lance before Clement died. Norah’s second husband was Sir Wilkie Collins, the chairman of Fortnum and Mason. Wilkie was significantly older than Norah, and following one of their many arguments, Wilkie disinherited her. However, she persuaded him to put her back into his will. He agreed but before he could sign it, he fell into a coma. According to Norah, Wilkie recovered some time later, and upon waking from his coma, following a walk around the grounds of their mansion, he demanded to sign the new will. Norah protested, wanting to wait for another day (she was more concerned about her husband’s health than the money, she says), but Wilkie argued harder, and so it was done. As soon as the will was signed reinstating Norah as his heir, Sir Wilkie Collins slipped back into a coma and died weeks later. Enter millionaire number three, Sir Bernard Docker – and plenty more drama.

While a work of non-fiction, the autobiography frequently wanders into the delightful realms of make-believe. If there was ever a book ready for film, this is it: Norah’s dialogue with her family and friends, her thoughts, memories and opinions are presented alongside a thorough description of the contents of each of her mansions and yacht, as well as in-depth depictions of articles in her wardrobe (undoubtedly useful for any filmmaker).

The aristocracy is in a different kind of trouble in F.M. Mayor’s The Squire’s Daughter. In this novel Sir Geoffrey De Lacy is struggling to run his mansion in the post-war world. The Squire’s daughter is Veronica (known as ‘Ron’), who gallivants around without a care as to her family’s plight. Her siblings, Oswald and Colette, are similarly only able to think of themselves. It is a brilliant observation of the dynamic between modern youth and the older generation. Ron does nothing but read erotic French novels and ride in fast cars while her father frets. Problems are posed but solutions are withheld.

When it was published in 1929 it had positive reviews. A critic in America’s Saturday Review of Literature said of the book’s subtle nature: ‘The older writers would undoubtedly have satisfied us. Their novels, once ended, would have been finished. But perhaps after all this newer is the greater art. Perhaps it is the very confusion that gives this book its illusion of reality. The author, like her people, sees no way out.’ We are currently enjoying a renaissance of F.M. Mayor’s work with the recently republished The Rector’s Daughter (first released in 1924) so surely there is room on our bookshelves for this title too.

Another book worthy of republication is E.M. Delafield’s Nothing is Safe. Delafield is best known for her hilarious novel The Diary of a Provincial Lady, about a woman juggling chaotic family life in the 1920s. Nothing is Safe, published in 1937 by Macmillan, occupies a similarly domestic sphere but shakes it up completely. It is a story of divorce told mainly from the perspective of the children. When the family separate and leave their lovely home in Hampstead, ten-year-old Julia wants to protect her younger brother, the quiet and sensitive Terry. Their mother’s new husband, the Captain, takes an instant dislike to the shy boy, mocking his fragility. On publication, the Aberdeen Press and Journal wrote that it was a book ‘by a humorist who is also a realist, and well done. The novel is notable’.

Other out-of-print books worth hunting down include The Green Knight by Iris Murdoch. Inspired by the medieval legend of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, it is a complicated story set in London in the 1990s. It opens with a dramatic death (was it self-defence or murder?) and the suspenseful consequences are explored across genres of magical realism and contemporary fiction.

Elizabeth Jenkins’s Dr Gully’s Story is based on the unsolved Charles Bravo poisoning case of 1876. Jenkins gathered together ‘all the biographical material’ she could find on the story to inform her book published in 1972. Dr Gully was a renowned physician whose patients included Alfred Lord Tennyson and Thomas Carlyle. Dr Gully had an affair with a young married woman named Florence who went on to marry the eminent lawyer Charles Bravo. At the time, Dr Gully and Florence’s relationship had diluted to a friendship; however, on hearing news of her marriage to Bravo, Dr Gully became enraged. Bravo died months later from poisoning, and while Dr Gully (and Florence) were suspects in his death, they were found not guilty. Jenkins’s novel was well received by readers and critics alike.

The Heroes of Clone by Margaret Kennedy (published in 1957) is a captivating novel concerning a young man called Roy Collins, an uncultured chap but with a passion for cinema, who has the goal of writing a script for Hollywood. His subject for his film is the life of a famous Victorian female novelist whose biography is much more colourful than he first thought.

Where to buy them

If any of the above have whet your appetite, then you’ll need to know where to find out-of-print books. Here’s my pick of the best options:

Online

ABE Books allows you to search for out-of-print books and then will direct you to booksellers around the world that have them in stock. Biblio offers a similar service.

On the high street

- For beautiful and rare books or first editions, Peter Harrington in London is well worth a visit. The shop has branches in South Kensington (stocking more than 20,000 volumes) and Mayfair.

- The Antique Map and Bookshop in Puddletown, Dorset

- Peak Volumes in Tideswell, Derbyshire

- Petersfield Bookshop in Petersfield, Hampshire

- McNaughtan’s Bookshop and Gallery in Edinburgh

- Cornell Books Limited in Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire

Is North London’s housing market recession-proof?

Of all the suburbs in Britain none has become quite so politicised as North London. This slightly leafy (and lefty) swathe in and around Islington – with Hampstead Heath marking its northern edge and Regent’s Park its southern boundary – is treated by our recent political leaders as a kind of shorthand for, to borrow a phrase from Suella Braverman, the ‘tofu-eating wokerati’.

Liz Truss took a dig at her privileged metropolitan enemies who ‘taxi from North London townhouses to the BBC studio’ to criticise her, ignoring the fact that Islington is not all Upper Street boutiques and multi-million pound homes. Islington is one of London’s most deprived boroughs, and more than a third of children in Camden live in low-income families.

Truss followed the party line set by Boris Johnson, who savaged the ‘trendy Islington lawyers’ leading the Labour party – conveniently forgetting that he once lived in the borough with his ex-wife Marina Wheeler, a King’s Counsel. Even Private Eye’s longest running cartoon is devoted to the grimness of life up North (London) – from its 100-pound shops to the need to decommission one’s home clay tandoor oven to tackle the cost-of-living crisis.

And yet for all the vilification and mockery, when it comes to property it is the owners of those North London townhouses who are laughing last. Camden has seen the strongest asking price growth of any borough in the capital over the past year, with prices up almost 13 per cent to an average of £1.073 million, according to new data from Rightmove. Islington has seen prices jump 8.5 per cent in the same period, to an average £797,000. London-wide asking prices grew 5.3 per cent. Research from estate agents Hamptons, meanwhile, shows that prices in Camden have leapt by 200 per cent in the past two decades, while prices in Islington are up 189 per cent.

For Dan Fox, a director of Savills in Islington, it is the patchwork flavour of North London’s micromarkets which sets it apart from the monotonous, affluent A3 corridor of South-West London. Think the peaceful villagey vibe of Belsize Park, the hip young family paradise of Stoke Newington, the elegance of Canonbury, the edginess of Dalston and the frenetic fun of Camden Town.

‘There are all these pockets, with real diversity between them,’ he said. ‘Other parts of London are a bit samey. Yes, it has lovely parts, but there is also a bit of grit about it. I think that around 60 per cent of the homes in Islington are local authority or ex-local authority.’

Buying agent Giles Elliott, a partner at The Buying Solution, agrees that North London’s appeal is partly its lashings of character; one-time country villages such as Highgate have managed to retain their individuality against the onslaught of chain stores and restaurants. It is also – obviously – leafy, and its landscape of valleys and hills adds an extra layer of personality.

In his experience young professionals head to Islington and Highbury for their starter flats, partly because it is close to the City. Many subsequently migrate towards Camden for its schools, joining dyed-in-the-wool locals. ‘There is a lot of old money in Hampstead and Highgate,’ he said.

Young celebrities also adore North London, lending it their considerable brand power. Harry Styles owns a compound of three houses in the same Hampstead street; actress Phoebe Dynevor, of Bridgerton fame, lives nearby. Normal People star Daisy Edgar-Jones is Islington born and bred, while model Georgia May Jagger exchanged the Jagger-Hall family’s palatial Richmond mansion, Downe House, for a home in Primrose Hill. Daisy Ridley, star of Star Wars prequel The Force Awakens, is renovating a Grade II-listed townhouse in Camden Town.

Fox thinks the Islington markets that will shine over the next difficult couple of years include Barnsbury, with its elegant squares and townhouses. ‘It is quite expensive, and so it will be less influenced by the cost of debt,’ he said.

The sought-after streets around Highbury Fields are also performing well, for similar reasons, while Newington Green, once a poor relation because of its lack of a Tube station, is starting to gain traction in the era of working from home thanks to its relatively affordable period housing stock and increasingly impressive array of independent cafes and restaurants.

It is lower down the market that Fox sees vulnerability – particularly small purpose-built flats in slightly dated buildings. ‘There are still first-time buyers, but the investor market has not really kicked in since the pandemic,’ he said. ‘They don’t need to buy so they are all now waiting to see if prices will fall.’

Elliott agrees that Camden’s urban villages, propped up by a disproportionate number of cash buyers, will sail through the coming years of austerity. ‘In the Islington borough where so many people work in finance I think there will be a greater sensitivity to changes in the market, because they are in the business,’ he said.

‘There was also such a rush to buy big properties in Islington earlier this year, with houses going to best bids and lots of froth. Now that has gone away, and what goes up must come down.’

The myth of the career woman

The image of the single, childless ‘career woman’ is drawn so sharply in our minds, so deeply ingrained in culture and overused in media, it obfuscates the real story. Contrary to popular belief, most working women are not putting their careers ahead of love, marriage and motherhood.

Never mind that there are no ‘career men’ – no one accuses a single, childless man of prioritising career over love and family just because he’s single and can pay the rent. But women are made to wear this label – though I have yet to meet a woman who has declined a date with a guy she’s interested in because she’d rather be on a Zoom call.

While university-educated women are settling down and having children later than was once the case, the ‘career woman’ is mostly a mid-century myth, an outlier like Mad Men’s Peggy Olson, who belongs to a time when women went to college to earn their ‘MRS’ degree. Young women who didn’t go to college, or didn’t find a husband at the fraternity mixer, were heralded in Helen Gurley Brown’s Sex and the Single Girl and encouraged to take advantage of the thrills of youth and independence before the responsibilities of marriage and motherhood. But it wasn’t long before second-wave feminism informed young women that there was no need to move on from the carefree, childfree life. Marriage and motherhood were aspects of patriarchal oppression, they warned, designed to keep women tied to the home. And so single ladies kept careering on, epitomised by just about any female lead detective, attorney or doctor on television then and now.

Don’t get me wrong. When I grew up in the 1970s, getting a college degree was never in question. Neither was finding a career. But I expected to also find love and get married, and I yearned deeply to have children. In fact, there was nothing I wanted more. Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique encouraged women to see having a career as additional to being anything she set her mind to, not an alternative.

The feminist narrative still urges us to believe that the childless daughters of hundreds of generations of mothers don’t want to be mothers because they have jobs

Yet the feminist narrative still urges us to believe that the childless daughters of hundreds of generations of mothers don’t want to be mothers because they have jobs. The record increase in late-age first-births proves that most women do; they hope love will arrive in time or choose single motherhood when it doesn’t.

In the meantime, these women are not crying into their keyboards, or sitting idly, swiping left and right, wiping away tears. While there are moments of deep grief after a break-up or another birthday without a birth – I was there myself in my late thirties and forties – these women invest their wealth in the happiness they can control, not lament what they cannot.

These lessons begin at university. Young women witness firsthand the gender divide on campus, where in America on average 60 per cent of undergraduates are women and 40 per cent men. The picture in the UK is similar. It’s the very scarcity of men on campus that is precisely why young women aim their career aspirations even higher, working even harder, besting the rate of men with degrees in just about every discipline but computer science, engineering and maths.

A 2012 University of Minnesota study asked: ‘Does a scarcity of men lead women to choose briefcase over baby?’ The researchers found that when women have few mating prospects on campus, they are more motivated to pursue ambitious, high-paying careers, knowing it may take more time to find a partner. In other words, women are not pursuing a career instead of pursuing love; they focus on creating wealth because men are scarce.

It doesn’t get easier. When there is a surplus of women to choose from, men no longer feel as much need to impress them and become less ambitious themselves. In other words, women’s higher-paying careers make it even more challenging for them to find a suitable mate.

‘Most women are unwilling to settle for men who are less educated, less intelligent and less professionally successful than they are,’ writes David Buss, psychology professor at UT Austin, in his 2016 essay, ‘The Mating Crisis Among Educated Women’. And the longer it takes for a woman to find a suitable mate, the less desirable she is to men who, as Buss says, ‘prioritise, for better or worse, other evolved criteria such as youth and appearance’.

Can women escape this paradox and find love? Richard V. Reeves, senior fellow at the Brookings Institute and author of Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male Is Struggling, Why It Matters and What to Do About It, believes so. Women are not seeking ‘breadwinners’ in male partners, he says. But they want men with a sense of purpose and direction. It’s not a man’s academic achievement or income a woman finds attractive; it’s that he can demonstrate that he has his life together.

And where are these men of great potential? Reeves’s book is in part about the men who are being demonised simply for being men. If women want to see the tide begin to turn, Reeves’s advice to women is to stop the ‘toxic masculinity’ talk and pathologising men and celebrate what they appreciate about the other sex. Men don’t need to be ‘empowered’ to become the men women want. They just need the opportunity to act like men seeking love. They need to feel welcome taking a risk and asking a woman out.

Despite having their first children later than ever, most women don’t ultimately choose their careers over love, marriage and motherhood. They prioritise careers when love takes time. When we see others for who they really are, what they really want – to be loved – both women and men will find the happiness they yearn for.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s World edition.

Matt Hancock comes third on I’m A Celeb

All of Westminster was glued to their screens on Sunday tonight to watch the final of I’m A Celebrity. For three weeks, SW1’s finest have watched Matt Hancock – the Casanova of the Commons – battle heroically against endless jungle-based challenges. The onetime Health Secretary has been covered in creepy-crawlies and subject to public opprobrium but against all odds, he had heroically made it to the last episode of this year’s series. Unfortunately, all good things must come to an end and Sunday night saw the end of the Hancock dream.

Much like his ill-fated 2019 leadership bid, Hancock promised much, but failed to deliver, with his luck running out in the celebrity jungle, just as it did in its Westminster equivalent. Despite snorkelling and being straddled by a bulbous toad, the West Suffolk MP could only come third, behind footballer Jill Scott and actor Owen Warner. Emerging from the camp, Hancock was met by the Bonnie to his Clyde: former taxpayer-funded aide Gina Coladangelo. The two embraced on the rope bridge, in scenes uncomfortably reminiscent of that infamous leaked CCTV tape.

Now all that awaits Hancock is a seething Chief Whip, his angry local constituents and the prospect of losing his seat come the next election. Suddenly, all those jungle challenges don’t seem so bad eh?

Why China can’t stop zero Covid

The Covid situation in China is not looking good right now. The authorities have trapped themselves into a situation from which there’s no obvious escape strategy. Whatever they choose – or will be forced – to do next will be very costly.

The country is extremely poorly prepared for a major surge of the virus

So far China has only managed to suppress Covid with brutal restrictions. Those are becoming increasingly untenable and the population is suffering. Unrest is spilling out into the streets in cities across the country. A major surge seems largely inevitable in the short term unless the authorities choose to enforce even more ruthless measures.

A major Covid wave in China would lead to a dramatic death toll. Current Omicron lineages in circulation are ‘milder’ than Alpha or Delta, but the associated morbidity/mortality is in line with early pandemic lineages for those with no prior immunity.

The country is extremely poorly prepared for a major surge of the virus. Very few people have acquired immunity through prior exposure and vaccination rates in the elderly are dismally low.

The population is not particularly young nor healthy (China's median age is 38 compared with a global average of 30) and its healthcare system is fragile, in particular outside major cities. It would be easily overwhelmed by any significant surge in Covid cases.

Hong-Kong faced a similar set of challenges earlier this year, and despite far better fundamentals (higher vaccine up-take and a more resilient health service), it fared poorly when Omicron spread as the below graph shows:

The most plausible scenario to me is that China will experience a major Covid surge in the near future leading to massive morbidity and mortality, which could be amplified by a collapse of the entire healthcare system.

Beyond the immediate death toll, the failure of their zero-Covid strategy would be difficult to handle by Chinese authorities, given the immense political capital they’ve invested into it since the pandemic began.

This article is an edited extract from Professor Balloux's twitter.

Yes, five million are on out-of-work benefits. Here’s the proof

How can 20 per cent of people in our great cities be on benefits at a time of mass migration and record vacancies? It’s perhaps the most important question in politics right now, but it’s not being given any scrutiny because the real figures lie behind a fog of data. But the fog is easily cleared, if you know where to look. What follows is for anyone with an interest in doing so, and it follows a few queries to The Spectator about how we found the five-million figure we’ve been using for a while.

To solve a problem, you need to recognise a problem

Every month, an official unemployment figure is put out on a press release – and news organisations are primed to cover it. It’s normally about 1.2 million looking for work: the problem, of course, is so few Brits are actually doing so. But the Conservatives have glossed over this point and had (pre-Sunak) taken to boasting that unemployment is at a 40-year low. In his last speech outside No10, Boris Johnson laid it on thick and said dole queues were shorter than any time since he was ‘on a space hopper’; Liz Truss made a similar boast as PM. But Rishi Sunak has not. There’s a decent chance that he will end the shameful cover-up and talk plainly about this huge issue.

The true benefits figure is not to be found on a press release, but buried in a password-protected DWP database with a six-month time lag. I don’t think the Tories intended to bury the bad news, but that is the effect of the rejig of their database. At The Spectator we have been tracking this measure since we were lambasting Labour for keeping five million on benefits during the boom. Here’s what it looks like…

The five million figure sounds so high as to be, quite literally, unbelievable. It was scrutinised on BBC Radio 4’s More or Less (episode here) but they didn’t go into detail. I mentioned it in a podcast recently and we were contacted by Full Fact, an independent watchdog who do a great job calling out people like me when we get figures wrong. I can see why they’d think it wasn't credible. If there were really five million on the dole – in the middle of an acute worker shortage – then surely the newspapers would be quoting this figure all the time? Didn’t the UK press go bananas when unemployment passed three million under Thatcher? So how could it be five million, without similar hype?

The five million figure ‘seems to be incorrect,’ Full Fact said in their email to us. ‘According to the most recent statistics, there are around 1.5 million people claiming out-of-work benefits.’ But the real figure is more than three times higher – but rather than reply to them, I thought I’d write this blog for anyone interested.

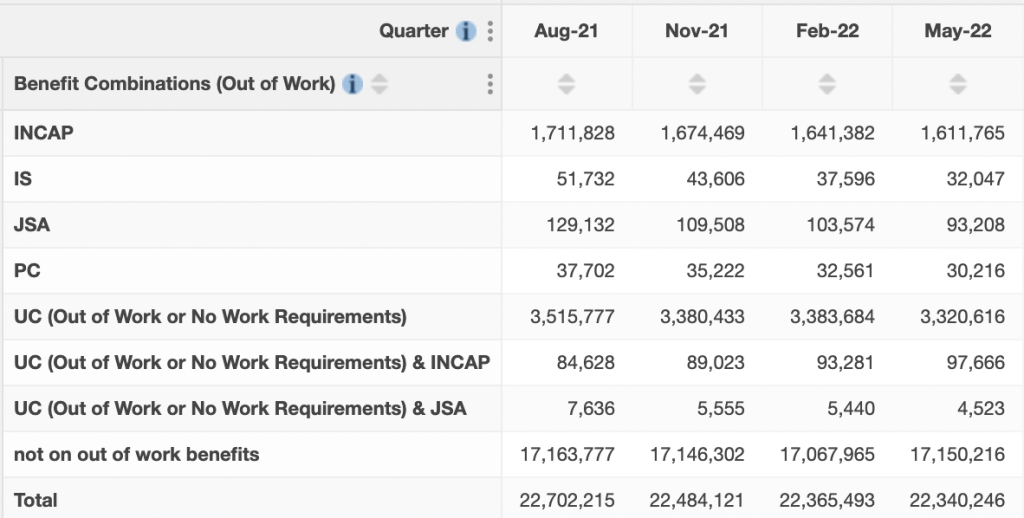

DWP data is now on Stat-Xplore, a versatile open data tool. The password bit is deceptive: you can bypass by clicking ‘Guest log in’ to find an Alladin’s Cave of data. Look at the dataset ‘Benefit Combinations – Data from February 2019'. Click Table 5, then click ‘Open table’ to get the numbers. A wheel appears while it computes, then the following table is revealed:

Add the figures on the right-hand column and you get 5.2 million. A call to the DWP press office will confirm that there is no overlap (every person is put in the category of the highest benefit they claim) and that 'out of work' is indeed the best phrase to describe them. The DWP offer no on-the-record guidance, for reasons that I’m unclear about. ‘Incap’ is Incapacity Benefit (or Employment Support Allowance – ESA – as it’s now known). IS is Income Support, which is being phased out. JSA is Jobseeker’s Allowance, now mostly replaced by the out-of-work part of Universal Credit.

There is a lot more you can do with this quite-versatile website. The data lag is six months (!) and it’s updated quarterly: the above is the November update, which runs to May. But it does allow you to look at the situation locally. Here’s a map, which my colleague John O’Neill has created. Quite a picture.

To fail to match up 1.2 million vacancies with at least some of those on out-of-work benefits is not just an economic failure but a moral one. But to solve a problem, you need to recognise a problem. Officially counting all five million people on out-of-work benefits would be a good way to start.

And a note to my critics

Ideally, an important study like this would be done by by a government department, or a think tank like the IFS. (The OBR has done great work, see here, but only occasionally). If officials are in no rush to publish embarrassing data, journalism can play a role in doing so. At The Spectator, we believe that journalism also means doing your own sums and hunting down your own metrics - it's hard to break new ground if you're using other people's metrics.

But might we be exaggerating for effect? The principle of The Spectator data hub is never to do so, and I'd like to reply to some people who have been so kind as to critique the above methodology

- We are using DWP language and methods: not our own. The DWP's definition of "out-of-work benefit", adding up categories and simply repeat the official wording. The OBR uses this method here (Chart E).

- The sharp rise in UC (Workless) We're repeating the official figures from the DWP. Its data may be corrupt, or its categories misleading. But we make no judgement about that, and repeat the official data with the official words.

- No double-counting The DWP say the figures do no double count. People are placed in the bracket of their highest welfare claim

- Yes, the figures include the terminally ill and those who cannot be expected to work. This critique is the main reason that this figure is not examined. In any society there will be some people who for various reasons are unable to work - but probably not 12 per cent of the potential workforce.

- If this five-million figure was real, why is no one else talking about it? Economists tend to focus on those actively looking for work, Tories have no incentive to highlight recent welfare failures and Labour dislikes the topic in general. Journalism has a bias towards readily-available and frequently-updated statistics- and these are buried deep in a DWP database.

I'd be grateful for any other challenge of thoughts. This is an under-explored part of public life, which arouses little general interest. Were it not for a couple of twists of fate, I'd have spent my life as one of these statistics. If this aroused half a much indignation as who gets into Oxford, we simply would not have such so much welfare dysfunction. I'd like to use what platform and influence I have to keep digging, and keep the conversation going. There is, still, all too much to say.

Justin Trudeau’s strange defence of his protest crackdown

On Friday, Justin Trudeau made his much-anticipated appearance before the Canadian Public Order Emergency Commission, where he gave testimony about his unprecedented decision to use the Emergencies Act last February to suspend civil liberties and suppress the trucker protests against vaccine mandates. Using the Act allowed Trudeau to freeze the personal and business accounts of the protestors without a court order, clear protestors in certain areas and force businesses (such as tow-trucks) to provide services against their will.

But to the fascinated eyes of the Canadian public, it soon became apparent that although the well-coached prime minister was present before the commission in body this week, in spirit he was with Alice in Wonderland – a magical place where words mean what you want them to mean.

The key task of the commission is to determine whether or not the protests last February met the definition of a public emergency for the purposes of the Act, to wit: ‘an emergency that arises from threats to the security of Canada (as defined in section 2 of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act)…’ that cannot be dealt with using ordinary powers.

If the situation met this definition, Trudeau is exonerated. If it did not, he is disgraced and ought to resign (though he probably won’t). Perplexingly, the system allows the prime minister to make his own choice of judge: Commissioner Paul Rouleau, appointed by Trudeau, will make the final call.

So how did Trudeau come to the conclusion that the honking horns, blocked traffic, bouncy castles, and dancing in the streets of the protests met the definition of a public emergency for the purposes of the Act? That’s what we all wanted to know, and when the commission lawyer invited him to explain, the nation leaned forward eagerly, cupping its ears.

Instead of answering, Trudeau smoothly responded with a question of his own – one that reframed the issue on his own terms. ‘The question is,’ Trudeau answered smoothly, ‘who’s doing the interpretation?’

Well, Mr Prime Minister, the lawyer pointed out, the definition is written out quite clearly in the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) Act. And the intelligence agency told the commission earlier that they assessed the situation at the time and determined that it did not, in fact, constitute a threat to the security of Canada as defined in the Act.

As you might say if you lived in Alice in Wonderland, words mean what I want them to mean

Upon which Trudeau explained carefully that the definition can mean one thing for the CSIS and another thing for the prime minister and the government. ‘It’s not the words that are different,’ he explained kindly, ‘the words are the same in both cases. The question is – who is doing the interpretation, what inputs come in, and what is the purpose of it?’

Or as you might say if you lived in Alice in Wonderland, words mean what I want them to mean. Let’s get this straight: the prime minister and his advisors decided they could interpret the Act as they pleased and discovered a ‘serious threat to the security of Canada’ existed, based on… what exactly?

Well, not on the assessment of the national security agency, apparently. Not on the recommendation of police forces, either, as the Commission has heard from police at every level, who have unanimously asserted that they did not ask for the Emergencies Act.

So, on what then?

On ‘threats of serious violence’ said Trudeau, while admitting there was no violence. ‘There was a sense that this was a broadly spread thing, and the fact that there was not yet any serious violence that had been noted was obviously a good thing, but we could not say that there was no potential for threats of serious violence.’ (It’s true, of course, that in every free human being there is technically the potential for threats of serious violence, so we could, in Trudeau’s charmingly passive double negative, not say that there was no potential for it at the protest.)

Earlier in the commission hearings, spectators were entertained by the interim Ottawa police chief’s admission that while there wasn’t actually any violence at the protest, it ‘felt’ violent.