-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Oddly unconvincing: Apple TV+’s The Essex Serpent reviewed

Having now watched it to the end, I would say that Slow Horses (Apple TV+) is by far the best TV drama I’ve seen in at least the last year: superbly acted and directed, ingeniously plotted, refreshingly free of annoyance. Oh, and I’d like to apologise to Mick Herron, author of the original novel series, which I now intend to devour. I’d say his understanding of the intelligence services is at least as jadedly insightful as John le Carré’s and I was quite wrong about his treatment of the ‘far-right’ threat. He gets it totally. The man is a genius.

But those hoping that Apple TV+ is going to supplant the increasingly rubbish, excruciatingly modish and content-lite Netflix as the new go-to subscription channel may be in for a disappointment. Certainly, the two new dramas I watched this week left me cold.

The first was The Essex Serpent, an adaptation of Sarah Perry’s bestselling novel about a sea monster – or is it? – that terrorises the populace of the Essex marshes in the 1880s. A decent production budget and starry cast led by Tom Hiddleston and Claire Danes are squandered on a dreary, convoluted, portentous drama with all the appeal of a fog blanket over a giant rotting fish which someone briefly mistook for a dead dragon.

Jamie Bell’s serial killer makes Hannibal Lecter look like Mary Poppins

Book groups and critics would have adored Perry’s leaden, overwritten and over-researched snooze-fest. I can tell that just by having glanced over a few pages. This is exactly the kind of novel people tell themselves they enjoyed rather than having actually enjoyed it. Whoever designed the exquisite cover deserves most of the profits because that’s what sold it, not the contents.

The same goes for the TV version. The title sequence of floral and snake patterns is enticingly beautiful. But the characters are awkward, the acting stilted (Danes having, apparently, put so much effort into Cora Seaborne’s perfect English accent she has nothing left for her inner life) and its depiction of Victorian England (despite the carefully recreated London and Rochester street tableaux) oddly unconvincing.

In an early scene, Cora demonstrates her independent spirit by bending down in the middle of street (despite her fancy dress and constricting whalebone corset, whose constricting constrictingness has been dutifully emphasised in an earlier woman-gets-dressed-in-Victorian-England scene) to listen through the drain to the sound of the hidden rivers gushing beneath the city. And you just go: ‘Nah. She wouldn’t.’

You don’t believe in the sea monster either. I’ve only seen one-and-a-bit episodes but I know – spoiler alert – that the serpent is just a metaphor or a collective delusion or some such. And I really shouldn’t be so sceptical at this stage but that’s how contrived and ersatz the whole enterprise feels. I don’t buy the weird, small, experimental surgeon chap with his implausible haircut; I don’t buy the far-too-intimate maid servant; I don’t care about the dishy reverend, even if he is played by raffish and intense Hiddleston. And if I want eerie atmosphere and sense of place, I’ll rewatch The Wicker Man instead. At least I can be sure that there’ll be a satisfying pay-off.

I can’t really see myself persisting with Shining Girls either. It’s about a Depression-era drifter who travels through time murdering young women. The thought of having to sit through eight whole hours of dripping ceilings and shabby stairwells and flickering lighting and pretty girls who might not have been hideously murdered if only they’d turned round when you shrieked at them is just too, too depressing.

This stuff isn’t aimed at men. It’s designed for young women who half want all their worst suspicions confirmed that round every corner is a rapist or a murderer. But to me this is contrived and exploitative.

Also, I feel as though I’ve seen a lot of it before. The supernatural menace recalls Pennywise, the clown/spider thing from It; the time-travelling serial killer is redolent of an old X-Files episode; and the 1990s Chicago newspaper for which our heroine Kirby Mazrachi (Elisabeth Moss from Mad Men) works is like all the newspapers that exist only on screen.

It’s definitely creepy and disturbing, if you like that sort of thing, especially the serial killer, played by Jamie Bell with such unsettling relish he makes Hannibal Lecter look like Mary Poppins. Also, it’s a neat idea the way one of the effects he has had on the heroine (whom he almost kills) is to trap her in a series of temporal glitches so that when she comes home, the decor is never the same, and her pet keeps changing from cat to dog. But I’m not sure this – nor the eventual, inevitable explanation – is going to be quite enough to keep me watching.

Hard to believe this rambling apprentice-piece ever made it to the stage: Almeida’s The House of Shades reviewed

The House of Shades is a state-of-the nation play that covers the past six decades of grinding poverty in Nottingham. The action opens in 1965 with a corpse being sponged down by an amusingly saucy mortician. The dead man, Alistair, sits up and walks into the kitchen where he natters with his prickly, loud-mouthed wife, Constance (Anne-Marie Duff). They seem to live in the city’s most dangerous dwelling. People keep dying. Then they come back to life to make a speech or two. Constance’s pregnant daughter doesn’t survive a back-room abortion and she shows up half a dozen times in a skirt dripping with blood. Alistair expires again and returns to life to tell us what it’s like to die. How the writer, Beth Steel, researched this experience isn’t clear. We have to take her word for it. Nye Bevan’s ghost shows up on a turnip patch and he explains that democracy can alleviate poverty by attacking property. Thanks, Nye. Very interesting. Granny collapses of something or other and returns from the dead to reveal that her career as an ill-paid skivvy was no better than being a ghost. Cheers, Gran. Sorry to hear that.

On and on this shapeless muddle grinds. Every half-hour or so the action leaps forward to a new decade. The chippy, witless dialogue seems to have been lifted from old Coronation Street episodes: ‘I’m the man in this house… you should be ashamed of yourself… marrying you was the worst mistake I ever made.’ The aggressive banalities are interspersed with heavy-handed references to political issues. Inflation, unemployment, privatisation and mine closures are mentioned but never properly examined. The level of analysis would bore a 12-year-old. A character in 1996 tells us that Tony Blair stands a good chance of becoming prime minister. Really? Who knew that? Each political controversy seems to anger every member of the household and they descend into foul-mouthed ranting and violence. It’s an odd way to characterise Labour’s grass roots: drunken screaming halfwits trying to kick each others’ teeth in. Perhaps that’s how Islington views Nottingham.

It’s hard to believe that a serious producer thought this apprentice-piece was ready to be staged

Some reviewers have praised Constance as an archetypal rebel, like Joan of Arc, but really she’s just a pretentious drunk who hates her kids and humiliates her husband in public. She can’t stop quoting Bette Davis and she harbours a weird ambition to work as a nightclub singer. The play keeps grinding to a halt so that Constance can change into a spangly frock and warble at us through a microphone. Great fun for the actress. Boring for the audience. And terrible for the drama which seizes up during these karaoke breaks. It’s not even clear if the songs are dream sequences or sincere attempts by Constance to become a crooner. The stagecraft is inept and careless throughout. Too many scenes end with a handful of climaxes where one would do. The writer doesn’t need a ghost, a house fire and a punch-up to bring a piece of action to a close. But she thinks she does. A writing coach might help.

Some scenes are so off-key it’s funny. In 1979 we meet an Asian woman who runs a bike shop and speaks fluent American. ‘May I use your bathroom?’ she says. Back then, no one said ‘bathroom’ to mean ‘loo’. And the phrase ‘kicks in’ to mean ‘starts’ didn’t arrive until decades later. If the writer doesn’t know her period she should ask someone who does. The accents are wonky too – more Yorkshire than Nottingham. It’s hard to believe that a serious producer thought this rambling apprentice-piece was ready to be staged. The Almeida needs to act like a proper theatre and not an amateur dramatics society for Arts Council trustafarians.

It would be a surprise if Grease the Musical could rival the 1978 movie, which burned itself into the memory of anyone who saw it the first time around. On stage, the gang of lads are less than wonderful. Too thuggish, too arrogant. Lacking in basic schoolboy charm. The girls are better but their roles are more interestingly written. The actors are already adding tired, mannered gestures as if the show had been running for 1,000 performances. More freshness is needed. Olivia Moore (Sandy) reaches dazzling heights in her weepy solo ballad, ‘Hopelessly Devoted to You’.

She’s the star of the show until Peter Andre arrives as Vince Fontaine. He only appears ‘at certain performances’, whatever that means, but he electrifies the crowd for a few brief moments on stage. Andre can move and dance and sing better than the rest. Plus, he knows he’s a star and he projects his magical aura into the farthest nooks of this enormous stadium. Why isn’t he the lead? On paper he’s too old to play a teenager but so was Travolta. He’s just the elixir this show needs. Make him Danny.

Are sanctions making Russia richer?

Before the invasion of Ukraine, it was by no means certain that there would be a united response from the West. The sanctions imposed on Russia after Vladimir Putin’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 were fairly limited, especially from the European Union. Germany pressed on with the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline to Russia. But now, America, Europe and much of Asia have been united in applying severe sanctions against Russian banks, companies and oligarchs. Three months on, it’s time to ask: are the sanctions working?

The answer from the Bank of Russia’s balance of payment data for January to April isn’t reassuring. It showed that the sanctions are emphatically not working, at least not in the way that they were intended. Russia’s current account surplus (roughly speaking: exports minus imports) jumped to an all-time high at $96 billion – almost four times the same period last year. The total balance of goods and services shows an even wider gap: $106 billion, treble that of last year.

At this rate, Russia’s current account surplus could hit $250 billion. So the extra money being banked by Russia is almost the same amount as the $300 billion of central bank assets and foreign currency reserves that were frozen by the West after the invasion.

Russia is not exporting more oil and gas. But the war – and the western sanctions – have massively driven up the energy prices. To be sure, Russia will suffer once its stockpiles of western goods and components are used up. Several companies will shut down and lay off workers. The recession will be very deep indeed.

But over time, the situation should improve for Putin. Germany – which relied on Russia for about 55 per cent of its natural gas and 34 per cent of its oil before the invasion of Ukraine – is insisting on a gradual phase-in of energy sanctions to give the economy time to adjust. If gas is to be shipped in, LNG import terminals will be needed. New suppliers and alternative sources of energy will have to be found. This delay gives Putin time. He will be able to obtain sanctioned electronics components through third countries (especially China) and find new export markets. Countries facing food shortages might also turn to Russian wheat, as well as Russian energy.

Where US-led sanctions have been more successful so far are in their secondary, indirect effects. For now, at least, Chinese companies operating in America feel they have to play along with the global boycott. Some have reduced exports to Russia voluntarily. But the Chinese government is seeking to reduce its dependency on the US financial system. If China insulates itself against any future US sanctions, Chinese companies may be more willing to supply Russia. Western sanctions are at their strongest right now because the world is dependent on the US dollar and the US financial market. That dependency will probably not last.

And let’s not hold our breath for Europe to cut out Russian gas. Olaf Scholz, Germany’s Chancellor, is being two-faced about this (just as he is being two-faced about arms deliveries to Ukraine). How can Germany expect to replace Russian gas while also cutting coal, ending nuclear and pursuing the transition to renewable energy sources at the same time? Scholz’s ‘clean energy’ programme is the raison d’être of Germany’s new SDP-led coalition.

It’s hard to find a German TV talk show that doesn’t feature a panellist arguing that Ukraine should capitulate to get Europe’s economy moving again. My guess is that Germany’s political establishment is playing for time, hoping that there will be a peace deal in Ukraine as part of which the sanctions will have to be loosened.

Russia’s best strategic option is to play a long game. Putin might dial down his offensive for the moment, bide his time – and wait until he is able to fund the next stage of his military operations. The West should operate on the assumption that the ultimate goal of German politics is to find a way to re–establish trade links with Russia. The apparatus of corporate Germany depends on repairing relations, which Putin understood when he encouraged the Nord Stream energy supply links in the first place.

Putin may be struggling in the military war. But I don’t think he is losing the economic one.

Beware the wrath of middle-class homeowners

‘Apocalyptic’ food shortages, gas and electricity bills soaring, wages not keeping pace with inflation… it’s beginning to look like we’re heading for major outbreaks of civil unrest this summer. As a resident of the London Borough of Ealing, which witnessed some of the worst rioting in the capital in 2011, I’m getting a little concerned. Not for myself and my family, you understand, but for the muggers, car thieves and burglars who prey on the middle-class residents. Will they be all right?

The educated bourgeoisie has developed an irrational fear of civilisational collapse, having been taught by books and films like The Road and Mad Max that gangs of marauding thugs will rule the roost in a post-apocalyptic universe. We’re told again and again that the moment law and order breaks down, our nice, leafy neighbourhoods will be transformed into Hobbesian hellholes. If bespectacled soy-boys like me aren’t killed for foolishly trying to defend our homes, the best we can hope for is to become indentured labourers while our wives and daughters are carried off on motorcycles.

We agreed we’d come with whatever weapons we had to hand – cricket bats, hammers, iron bars

But as I discovered during the disorder of 11 years ago, it is not middle–class property owners who have the most to fear from the breakdown of society, but the propertyless. This revelation hit me during a long day in August 2011 that began with a trip to Ealing Broadway, the site of the worst rioting the night before. It’s about a two-mile walk from my house, and as I made my way along the Uxbridge Road I could see exactly where the rioters had got to the previous evening, like a tideline in the urban landscape. On one side of the line it looked as it always does – the usual hotchpotch of restaurants, coffee shops and newsagents along the main road, with quiet residential streets behind – whereas on the other there were broken shop windows, burnt-out cars and upended bins, as if the area had been engulfed by some terrible destructive storm. That line was about half a mile from my house.

By the time I got to the Broadway it was too late to help with the clean-up, so I decided to wander back via a street of Victorian semi-detached houses just like my own. Had the sea of rioters flowed exclusively along the main thoroughfares or been diverted along residential streets? They’d been diverted. Everywhere I looked, householders were boarding up their windows, sweeping broken glass off their front steps or standing by their damaged cars, waiting for tow trucks.

I asked one man what had happened and he said a pack of feral youths had tried to break into his home at around midnight. He’d locked his wife and young child in the garden shed for their own safety and then done his best to keep out the mob as they tried to break down his front door and smash their way in through his front window. ‘Didn’t you call the police?’ I asked. ‘Yes, of course,’ he said. More than 12 hours later, they still hadn’t turned up.

I hurried home, convinced the riots would reach my street that night and desperately trying to think of ways to protect my wife and children. I asked the head of the local Neighbourhood Watch group to convene an emergency meeting and, not surprisingly, it was well-attended. There were about 30 of us, nearly all men, and we agreed we wouldn’t risk anything to protect our cars. If lawless youths wanted to smash them up or set them on fire, so be it. But if they tried to break into our homes, we would act. We agreed that the householder being targeted would set off his burglar alarm and the rest of us would come running to help, using whatever weapons we had to hand – cricket bats, hammers, iron bars.

Thankfully, the Metropolitan Police reasserted control that night and the riots fizzled out, so I don’t know what would have happened if our worst fears had been realised. But I suspect some of us would have come to our neighbours’ defence. Had that transpired, I don’t fancy the chances of the housebreakers. And this would have been on day four of the worst outbreak of civil disorder since the Brixton riots. By day seven, if the police were still nowhere in sight, I expect my Neighbourhood Watch group would have formed itself into an armed militia, with pickets at either end of the street.

The depiction of civilisational collapse in Hollywood movies, in which the usual social hierarchy is turned on its head, is clearly a myth. Middle–class pantywaists like me will be absolutely fine. It’s the criminal underclass who should be living in fear.

For Boris, the hard bit is just beginning

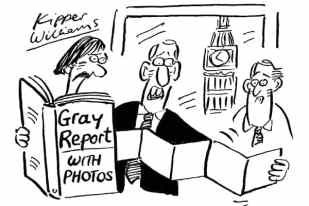

Boris Johnson has been plunged back into the mire of partygate. The publication of a photograph of Johnson raising a glass to his departing communications chief Lee Cain in November 2020 and the long-awaited report by Sue Gray into lockdown breaches in Whitehall means that once again there are Tory MPs publicly calling for him to resign. Some of those who had gone quiet on the basis that the war in Ukraine meant it was not the right time for a leadership election have renewed their calls for the Prime Minister to go.

No. 10’s hope is that apologies and an emphasis on how the new Department of the Prime Minister is meant to professionalise Downing Street will be enough to persuade backbenchers to stay their hands. Johnson’s loyalists will make much of Gray’s statement that some of her recommendations on how to better organise Downing Street are already being acted upon. But the worry for Johnson is that the Gray report, which was less bad for Downing Street than many had expected, is still not the end of the matter – there is the investigation by the privileges committee to follow. As one senior backbencher laments: ‘It is just very hard to see how this ends.’

Johnson’s closest allies have been most worried about the parliamentary inquiry into whether the Prime Minister misled parliament or not. The very fact that the inquiry is happening reveals how dangerous it is for him. The government had hoped to defer the decision on whether to have the investigation until after the police and Gray had reported, but Tory MPs would have refused to vote for that. They might not be prepared to oust the Prime Minister, but they also want to indicate that they do not support what went on. The MPs on the privileges committee will have to vote on a report into whether Johnson did or did not mislead parliament, and on whether, if he did so, it was deliberate or not. One Johnson ally frets that he ‘cannot see a friend on that committee’.

The best Johnson can hope for from the privileges committee is a rebuke for not having corrected the record earlier when it became clear that there had been rule breaches in Downing Street. If the conclusions are any more damning than that, then he will be in an almost impossible position. One former cabinet minister who thinks Johnson should go says that although the parliamentary party doesn’t have ‘much of a spine’, Tory MPs couldn’t accept Johnson staying in his post if the committee concludes he deliberately misled the House.

Even without partygate, the next few months will be hard for Johnson. Inflation is making nearly everybody poorer. The squeeze on discretionary household spending being caused by rising energy prices could be enough on its own to tip the country into recession.

‘The cost-of-living crisis has only just begun,’ warns one No. 10 source. The price of food is going to spike significantly in the coming months. Andrew Bailey, the Bank of England governor, might have been foolish to describe the coming increases as ‘apocalyptic’, since the line was unhelpful to consumer confidence, but he was not wrong.

The government can take measures to try to help people with rising prices. But even before last month’s energy price hike the government had spent £9 billion on trying to help households to deal with the raised energy price cap. This support provided little respite from demands for the government to do more. The test for the support package the Treasury is working on is not just whether it eases the pressure on the poorest households but whether it is politically sustainable, whether it can hold until the autumn Budget.

Parties, inflation and scandal make a bad backdrop to the by-elections due to take place next month

The coming public sector pay settlements promise to be particularly difficult. They will be lower than inflation, and so constitute a pay cut in real terms. In the tight labour market, this will further increase staffing pressures and make it harder to deal with the backlogs caused by Covid and lockdowns.

Parties, inflation and scandal make a bad backdrop to the two by-elections due to take place next month in Wakefield in Yorkshire and Tiverton and Honiton in Devon. The two seats are very different. The Tories took Wakefield from Labour in 2019 for the first time since 1931. By contrast, the Tories have held Tiverton and Honiton since the seat’s creation in 1997, and have a 24,000 majority there. But many Tories are expecting to lose both seats, which would instil fear in MPs in both traditionally Labour seats that recently turned blue and those in classically Tory rural areas. The fact that Labour and the Liberal Democrats can concentrate their resources while the Tories are having to fight on two fronts will worsen these worries.

Of course, there are unique circumstances in both of these seats. It would be extremely odd for a party to hold a marginal seat where its MP had been sentenced to 18 months for sexual assault of a minor. And even a safe seat becomes vulnerable when the previous MP resigns because of a scandal, in this case for watching pornography in the Commons chamber. But losses at both ends of the Tory voting coalition will lead to a lot of nervous MPs. They will look at the swings in the two seats and calculate what it means for their own prospects. The worry for No. 10 is that there may well be more by-elections in the coming months. Regular by-election defeats will make the parliamentary party particularly skittish.

In recent months, Johnson’s new No. 10 set-up has had something of a honey-moon. Backbenchers approved of its more political focus, and Johnson benefited from the fact the government has undoubtedly shown leadership on Ukraine. Yet, as one cabinet minister complains, the government still ‘hasn’t got a defining mission’. The lack of a domestic agenda means that the government doesn’t have a sense of purpose it can draw on to provide stability in a crisis. No. 10 will now have some of the most difficult months to weather that any government has faced, and it will have to do so with limited political capital.

The return of the implausibly moreish Borgen

A decade ago the unthinkable happened: a subtitled TV drama about people agreeing with one another went global. On paper it bore the hallmark of a barrel-scraping pitch from Alan Partridge. Somewhere between youth hostelling with Chris Eubank and monkey tennis, he might easily have proposed a new ne plus ultra in implausible entertainment concepts: Danish coalition politics.

Yet Borgen caught a thermal and soared. The show took its name (which, correctly pronounced, sounds like a Cockney saying ‘Bolton’) from the so-called fortress in the heart of Copenhagen where state business is conducted. It featured Birgitte Nyborg, a moderate heroine who snuck into Denmark’s highest office through a small centrist crack between left and right. Embodied by Sidse Babett Knudsen, whose background was all in comedy, there was steel in her eye and sandpaper in her voice – but that gigawatt smile of hers could melt a thousand icecaps.

Perhaps unconsciously groomed by Borgen, before the second series aired Danes elected their first ever non-fictional female statsminister. Helle Thorning-Schmidt, professing herself a fan, compounded international interest in the show. Though France was the earliest adopter, the UK was soon rapt as BBC Four pumped out episodes in pairs of a Saturday night. It helped that, for the first time in for ever, we too were experiencing the befuddling Euro-hybrid of coalition government. The cross-party cabinet was said to include students of Borgen.

We’d all been softened up for it by The Killing, the viral whodunnit from Danish state broadcaster DR which had political subplots hardwired in. But in lieu of Nordic noir, this was Nordic nice. Borgen’s stars (the ones who weren’t already known from The Killing) became familiar faces. Babett Knudsen, an impeccable English speaker, made two movies with Tom Hanks. Birgitte Hjort Sorensen (who played news anchor Katrine Fonsmark) and Pilou Asbæk (spin doctor Kasper Juul) both popped up in Game of Thrones.

Borgen was a ne plus ultra in implausible entertainment concepts: Danish coalition politics

DR almost never commissions a third series of anything, but Borgen was a cash cow projecting soft power and so Nyborg, out of office and newly divorced, formed a new party and electioneered her way back to her spiritual home, now as foreign minister. And that was apparently that. After 30 episodes currently bingeable on BBC iPlayer, audiences were left to imagine Nyborg exporting her moreish brand of Scandi consensus around the planet in perpetuity.

And yet here are Sidse Babett Knudsen and showrunner Adam Price on my screen explaining why Borgen has returned.

‘We said to each other back then,’ says Price, ‘that if the right story came along we would try to bring it back at some point in the future. It’s just the sort of thing you say at a wrap party.’ Babett Knudsen pipes up: ‘And I said, “We’ll talk about it again in ten years.” I lived very well without Borgen. I was doing fine and then Adam came and said: “I have the story. It wasn’t really intended for the Borgen universe, but do you think maybe we should move it there?”’

In those ten years Price, who in Denmark has a side hustle as a celebrity TV chef, was slated to form a scriptwriting power couple with Michael Dobbs, creator of House of Cards. Their collaboration didn’t bear fruit. Perhaps elements of it have resurfaced in the new Borgen’s thrillerish plot, which topically enfolds fossil fuels and global warming, Russian badassery and arm-wrestling between the US and China.

Some of the story is set in post-colonial Greenland, which, lest we forget, Donald Trump once tried to buy. More pertinently still, in Mette Frederiksen, Denmark now has its second female statsminister. So does Borgen. When it was broadcast in Denmark earlier this year, viewers spotted that power-hungry new PM Signe Kragh is somewhat modelled on Frederiksen, speaking with the same accent, being adept at Instagram and a devotee of canned mackerel. These and other contemporary matters arising from the series – from Twitter trolling to green activism – were all food for thought as politicians, reporters and Borgen stars discussed each episode on a special weekly edition of DK’s Det Politiske Talkshow.

I ask Babett Knudsen if she has ever met either of her factual equivalents. ‘No,’ she says. ‘It is completely deliberate. To me it’s just super-essential that I have to stay within the world of Borgen to believe in it, which is also why, when we’re shooting, I can’t watch the news.’

Instead it’s Price who’s been glued to the headlines, even seeming to foretell them. The first episode, which alludes to aggression against Ukraine, was launched in Denmark four days before Russia’s invasion. ‘Actually Birgitte is referring to the Crimean war in 2014,’ he says. ‘It just sounds as if it has just been written. That’s just the terrible chance of fate.’

Reinstalled as foreign minister, it’s Nyborg’s task to swim with the superpowers while fighting her corner in the coalition and quashing unrest in her own party. At home she also wrangles with her son Magnus, once a little blond cherub but now a strapping and querulous eco-warrior. (The rest of the returning cast look ten years craggier.)

Otherwise her personal life is a void. Blessedly there is no sign of the colourless British starchitect she dated in the third series. I ask what happened to him. ‘Terrible terrible tragedy,’ deadpans Babett Knudsen. ‘He got run over by a bicycle and you don’t think of these things as being dangerous but bicycles are, like, really really dangerous in Copenhagen. He was so young and so fit. And we had great sex until the end.’ She then slips in and out of the first person. ‘It’s always been a secret little dark wish that one day I will be able to devote myself completely to my work. Birgitte experiences this as freedom. She thinks she is having her time of life. But the camera is showing something different.’

A trigger warning for fans of Birgitte Nyborg’s pragmatic idealism: it’s weirdly upsetting to witness her moral disintegration across eight episodes. Price cites Lincoln’s bon mot that served as the epigraph for a previous episode: ‘Nearly all men can stand adversity, but if you want to test a man’s character, give him power.’ Not for nothing, along with a new signature tune and a new home on Netflix, is there a portentous new title: Borgen – Power & Glory.

The international takeaway from Borgen was that the Danes are just much nicer than the rest of us. But this series portrays realpolitik red in tooth and claw. I ask Price if we haven’t misread the national psyche?

‘I don’t think you have. I think we are quite nice. We don’t believe that the system is rotten and we very much believe in our democracy and that is a core value to Birgitte Nyborg as well.’ As he lionises his fictional heroine, the woman who plays her plants a loving kiss on his cheek. ‘Ooh yes,’ he says, ‘keep doing that.’ Now that they’re back, will they keep doing Borgen? ‘The possibility is there,’ is all he’ll say.

We need Nyborg. In the real world, it has taken war in Europe to throw up a political leader that the West can agree to admire. Before Volodymyr Zelensky became president, he played one, which must be somewhere in the back of my mind when I ask Sidse Babett Knudsen if Birgitte Nyborg can be relied upon to save the world. She pauses for thought, unleashes that gold-medal smile and says: ‘Of course.’

How I fell in love with the blues

I was never into the blues that much. I listened to a bit of Roy Buchanan and Rory Gallagher but only as accidental overspill from rock. I knew the Rolling Stones’s sound came out of their love of the blues but what they added was more important (to me) than what they took. And then there was Eric Clapton. In common with a discerning portion of the British population, I loathed Clapton after his drunken endorsement of Enoch Powell’s rivers-of-blood speech. Even if I’d somehow let that slide, I could never forgive him for ‘Tears in Heaven’ which was like having a bucket of oversweetened bilge water poured over one’s head. Musically, Clapton hasn’t come up with anything interesting for at least 40 years so why anyone showed up at his annual plod-alongs at the Royal Albert Hall is an enduring mystery. Overall, no one has done more than Clapton to turn British people off the blues.

I liked it when jazz musicians played the blues, especially if the word was embedded in the title of a tune – ‘When Will the Blues Leave?’ (Ornette Coleman), ‘Blues for a Reason’ (Chet Baker), ‘The Hard Blues’ (Julius Hemphill) – but as a distinct musical genre the blues never quite got through to me. I liked bluesness as a musical ingredient and liked some of the names – Howlin’ Wolf, Son House – more than their music. Obviously I loved Dylan’s ‘Blind Willie McTell’ but listening to McTell himself was a come-down after the Dylan song. Then, a few years ago, my wife and I drove with friends from Austin, Texas, down to Mississippi – and nothing really changed. Geographically, the Delta was a revelation – the way it just lay there, like a kind of spatial waiting – but we didn’t go to any gigs. We ate at a café in B.B. King’s home town and I think we drove past Robert Johnson’s grave, but we didn’t stop and the whole trip was unaccompanied by music because the car didn’t have a functioning sound system.

Miles Davis expressed his contempt for the idea that black people played the blues because they were poor

I only really got into the blues in LA, after my friend Richard Grant – an English writer living in Mississippi – sent a Spotify link to something he called ‘trance blues’. That snagged my attention immediately. I’d loved psychedelic or Goan trance; more generally, what I’ve wanted from any kind of music – Bach, Keith Jarrett, Indian classical – is to trance out to it. The guy inducing this particular trance was called Junior Kimbrough, and his laid-back, one-chord, hill-country drone was all-enveloping. Intense though it was, my enthusiasm for Kimbrough remained self-contained, didn’t extend beyond him. Then, last year, Richard suggested that I listen to some tracks on R.L. Burnside’s album Too Bad Jim. From there I went back to Burnside’s earlier acoustic recordings and forward to the various remixes put out by Fat Possum Records. Feeding a familiar, life-sustaining urge to find out as much as I could, I consulted discographies, watched all available footage of him on YouTube. As often happens, this surge of interest was accompanied by an undertow or riptide of regret: that I’d never seen him play, had never been to a juke joint (if only I’d been to Junior’s place where parts of Too Bad Jim had been recorded!). By the time Kimbrough and Burnside became famous, in the early 1990s, they were both in their sixties, old and plump enough to play sitting down, rocking hard in the still centre of the beat. Junior died in 1998, before I began spending a lot of time in the US, but I could easily have seen R.L., who died in 2005.

The idea of authenticity has haunted the blues from the time, at least, of John Lomax and his fractious relationship with Lead Belly. As a student at the Juilliard Miles Davis, whose dad was a successful dentist, expressed his contempt for the idea that ‘the reason black people played the blues was because they were poor and had to pick cotton’. Still, the hard lives of Kimbrough and Burnside – rural poverty, farm-work and, in Burnside’s case, time served in Parchman for murder – were rooted in a whole mythos of the blues. Their label, Fat Possum, cannily exploited this while maintaining an authentically Davisian indifference towards any music that sounded like a dutiful old horse, ploughing a furrow that had already been worked to death. Even though, in Burnside’s case particularly, you can hear the influence of John Lee Hooker, it’s obvious that he’s advancing the form. And not only that. He and Kimbrough were doing this way before they were ‘discovered’ in the 1990s.

There’s amazing footage shot in 1974 at a place called, rather grandly, the Brotherhood Sportsmen’s Lodge. It actually looks like a low-ceilinged house party with R.L., skinny, grinning and standing, playing electric guitar and singing while trying to avoid the jostle he’s whipping up around him. On the second track, ‘Jumper on the Line’, he sets up a choppy riff that deepens into something that has the relentless drive of funky techno. People are dancing, naturally, but by the end we are on the ecstatic brink of rave – in 1974. One guy in particular is completely gone. He could be at Berghain in Berlin or one of the big dance parties in London when electronic music was at its sustained and blissful peak. But there’s something else, too, something specific to the blues, to the part of the world from which it emerged and, ‘against tremendous odds’, flourished. The phrase is from Deep Blues by Robert Palmer who played a big part in the late change in the fortunes of Kimbrough and Burnside (he produced Too Bad Jim). At the end of the book Palmer quotes Wadada Leo Smith, a jazz musician who was raised in the Delta. Growing up in that environment, Smith says, made him feel that whatever he plays ‘relates to a gigantic field of feeling’.

Listening to Kimbrough and Burnside I feel that, at last, in my early sixties, I’ve entered a corner of that foreign field, that vast and crowded zone of meaning.

How profitable are Britain’s biggest oil companies?

A slip of the tongue

George W. Bush condemned a political system where one man could wage a ‘brutal and unjustified invasion of Iraq’ before correcting himself and saying ‘Ukraine’. Some other Freudian slips by US politicians:

– In the 2012 US election Senator John McCain, who had been the Republican candidate four years earlier, made a speech in which he attempted to look forward to a Mitt Romney presidency, but somehow managed instead to say: ‘I am confident that with the leadership and the backing of the American people, President Obama will turn this country around.’

– At another event in the same election, Romney himself introduced his running mate, Paul Ryan, as ‘the next President of the United States’.

– As for Barack Obama, he made a speech on penal reform arguing that America must make sure it was not ‘incarcerating non-violent offenders in ways that renders them incapable of getting a job after they leave office’.

Oil profits

How profitable have Britain’s two largest oil companies been in recent years?

BP / Shell

2021 £11bn / £18.1bn

On turnover of: £128 bn / £213bn

2020 -£-17.2bn / -£19.9bn

2019 £6bn / £17.9bn

2018 £11.6bn / £27.7bn

2017 £4.9 bn / £15.2bn

Retail price peaks

The Consumer Prices Index reached 9% and the Retail Prices Index (RPI) 11.1%.

How does that compare with post-war peaks in RPI?

June 1948 9.7%

Jan 1952 13%

April 1956 7.3%

April 1958 4.9%

May 1962 5.7%

April 1965 5.6%

March 1969 6.3%

Aug 1971 10.3%

Aug 1975 26.9%

May 1980 21.9%

June 1989 8.3%

Sept 1990 10.9%

Cost of living misery

How is the cost of living impacting on our sense of wellbeing?

25% of adults report feeling lonely some or all of the time.

34% say they are suffering high levels of anxiety.

88% say the cost of living has risen over the past month.

41% say they are buying less food when shopping.

38% say they are spending more.

43% are still worried about Covid-19.

Source: ONS

Inside Taiwan’s plan to thwart Beijing

Taipei

Nowhere is watching Russia’s faltering attempt to crush its democratic neighbour more closely than Taiwan. The Ukraine war is seen in Taipei as a demonstration of how determined resistance and the ability to rally a global alliance of supporters can frustrate a much larger and heavily armed rival. Taiwan has spent the past few years planning how it would cope if China attacked. It is developing a doctrine of defence warfare right out of the Ukrainian playbook.

China was carrying out military exercises off the east coast of the island last week when I met Joseph Wu, Taiwan’s foreign minister. ‘They keep circling in that area,’ Wu says. ‘Nonstop for two weeks, and it is very threatening.’ There were also reports of China carrying out missile training exercises in its remote northwest, simulating attacks on a Taiwan naval base. ‘We are on the front line against authoritarianism,’ he adds. ‘The reaction to Ukraine here is very strong because it is a mirror image of what might happen to Taiwan in the future.’

Joe Biden makes the same argument. The theme of his five-day trip to Asia this week was that world affairs are being redrawn and the dividing line is not Russia vs the West but ‘autocracy vs democracy’. When asked, the US President said that America would defend Taiwan – a break from the official policy of strategic ambiguity.

No democratic country is more aware of Taiwan’s role in the ‘front line against authoritarianism’ than Japan, whose Senkaku Islands are much closer to Taiwan than the Japanese mainland. The islands are also claimed by China and would become essentially indefensible if Taiwan fell. Fumio Kishida, Japan’s new prime minister, has slapped sanctions on Russia and joined Germany in pledging to double his country’s defence spending. Kishida was in London earlier this month, talking with Boris Johnson about a Japan-UK defence pact.

Such talk is intended to make Xi Jinping pause for thought in his plans for China’s reunification with Taiwan. One reason the western alliance is equipping Ukraine with hi-tech anti-ship missiles, used to great effect against the Black Sea Fleet, is to demonstrate to Beijing that any amphibious assault comes with huge risks. But Xi can also learn from Vladimir Putin’s mistakes. ‘We might have a breathing space,’ Wu says. ‘But they are learning [from Ukraine] so they can improve their military activities, and if they think they have overcome the difficulties of the Russian military, they might be tempted to use force.’

Ukraine’s resistance – and the speed with which ordinary citizens turned into guerilla fighters using portable Javelin and Stinger missiles – has reinforced faith in what Taiwan calls its ‘porcupine strategy’. This plan predates the Ukraine invasion and is credited to Admiral Lee Hsi-min, who headed the island’s armed forces between 2017 and 2019. He argued that Taiwan could not fend off China in traditional warfare (Taiwan’s defence budget is $17 billion this year, while Beijing’s is an estimated $288 billion), so should not waste money on a large defence force. Taiwan had to be smarter.

Taiwan’s elaborate sea defences include forests of steel spikes, layers of mines and ‘seawalls of fire’

Among the small, lethal and mobile systems that Admiral Lee pushed for were fleets of mini assault boats, equipped with anti-ship missiles and based in small fishing ports. They’re easily hidden and immune from long-range missile attacks. ‘You should re-define winning of the war,’ Admiral Lee says. ‘Don’t try to destroy the enemy totally in the battlefield. You just need to ensure the enemy fails to accomplish their mission. You need to be robust, make your enemies believe it is impossible to take over Taiwan. Then you are safe.’

A Chinese invasion would probably begin with a blockade or the seizure of small Taiwanese-controlled islands closer to China. But much like Putin’s original plan for Ukraine, an invasion would rely on overwhelming force. Estimates vary, but it would require up to two million combat troops, along with thousands of tanks, artillery pieces, rocket launchers and armoured personnel carriers. All of these would need to cross the Taiwan Strait in a fleet that would include thousands of requisitioned ferries. Preparations would be impossible to hide.

Might China’s army run into the same problems as Russia’s? Taiwanese strategists see parallels and opportunities. ‘The Taiwan Strait is actually the highway for the Chinese army, where they are most vulnerable,’ according to Su Tzu-yun, a research fellow at the Institute for National Defense and Security Research in Taipei, a military–linked research group. Taiwan’s coastal terrain is a defender’s dream: only 14 of its beaches are regarded as suitable for an amphibious landing. Most of the east coast is made up of cliffs, while beaches on the west coast are lined with densely populated towns, mud flats, paddies or other coastal ponds. It could be designed to slow down an enemy advance.

So the challenge for an invader is far greater than Russia’s land invasion and, despite recent years of rapid modernisation, the People’s Liberation Army is still notably poor at ‘joint operations’. Just a few weeks ago, the state-owned newspaper PLA Daily admitted that China needs more military leaders capable of thinking across the traditional navy, air and land divides.

Then there are the treacherous waters and winds of the Taiwan Strait, known locally as heishuigou or the ‘Black Ditch’, which mean there are only two realistic windows for an invasion every year: late March to the end of April, or late September to the end of October. Taiwan’s elaborate defences against attack from the sea include forests of steel spikes, layers of sea mines (to protect the approaches to the vulnerable beaches) and ‘seawalls of fire’, an underwater system of pipelines to release gas and oil ahead of advancing invasion forces. They would be ignited by gunfire.

Taiwan’s democracy itself is seen in Taipei as one of its most important defensive assets. The island, which was a military dictatorship until the 1990s, is one of the world’s most successful new democracies, so it can claim to be on the right side of Biden’s ‘democracy vs autocracy’ divide. A Chinese invasion would be seen by the West as an assault on the principles of liberal democracy and self-determination. Since 90 per cent of the world’s top-end microchips are made in Taiwan, the island’s role in the global economy is also crucial. There is a joke in Taipei that if Chinese missiles started falling, the best place to shelter would be in microchip factories, because they are so vital they can’t possibly be targeted.

The US is Taiwan’s principal arms supplier. But Biden’s verbal assurance that he would defend Taiwan is not something the Taiwanese will depend upon. ‘We want to show the international community that we are willing and we are determined to defend ourselves,’ says foreign minister Wu. As Admiral Lee put it: ‘The only thing you can rely on is yourself.’

Wu says he was personally surprised by western unity and resolve over Ukraine – and believes it probably came as a shock to Beijing too. ‘This is good for Taiwan in the sense that if China wants to attack Taiwan, we hope the democracies can also unite together in reacting to the Chinese aggression.’ Biden now talks as if the future of the US-led (or ‘rules-based’) world order is on the line in Taiwan. If the island fell to China, that would signify the end of the long American century. China would be the dominant power in the world’s fastest–growing and most strategically important region. America’s regional allies – Japan and South Korea – would have little choice but to reach an accommodation with Beijing.

The Ukraine war is almost obsessively covered in the Taiwanese media. Wang Jui-ti, a 35-year-old Taiwanese citizen, became an instant celebrity when he signed up for Ukraine’s foreign legion, the International Legion of Territorial Defence of Ukraine, and began posting from the front line. ‘I want to do my part to defend basic human values,’ he said.

There has been much coverage of the bravery and will to resist shown by young Ukrainians, which seems to have affected young Taiwanese. Polls conducted after the start of the war show a sharp increase in the number of people willing to fight for their country in the event of a Chinese invasion – 70 per cent say they would take up arms. This has, in turn, encouraged government plans to revamp the island’s territorial defence forces. Ukraine has shown the world what a determined citizenry can do.

In many ways Taiwan is already at war: a grey war. As well as routine military intimidation, Taiwan faces constant cyberattacks, many of which target its hi-tech companies. It is also the most targeted country for spreading false information, according to the Sweden-based V-Dem Institute.

The official charged with countering this is digital minister Audrey Tang, who has devised a defence called ‘humour over rumour’. It works closely with comedians to rapidly respond to Chinese disinformation with a joke or a meme, and a short factual repudiation. ‘The idea, very simply put, is to make the clarification even more viral than the conspiracy theories,’ said Tang (who is also Taiwan’s first openly trans-gender minister).

China’s grey warfare had for many Taiwanese become almost background noise, something they had learned to live with. Russia’s aggression has been a wake-up call. ‘We should thank Ukraine. It’s good for Taiwan,’ an elderly taxi driver said to me as I headed back to the airport. Then he asked if I thought China would still invade. It was a question I heard many times in Taipei. Thanks to Ukraine, the Taiwanese realise they can’t afford to wait for an answer.

Boris Johnson’s guilt

An ability to survive narrow scrapes has been one of Boris Johnson’s defining qualities. The pictures of Downing Street’s lockdown social events included in the Sue Gray report were so dull as to be almost exculpatory: staid gatherings of half a dozen people around a long table with sandwiches still in their boxes, apple juice poured into a whisky glass. Far worse happened in No. 10 but Gray did not publish those photos or look into (for example) the ‘Abba’ party in the No. 10 flat, saying she felt it inappropriate to do so while police were investigating. Luckily for Johnson.

The more damaging material came from the emails intercepted, with No. 10 staff being clear that they knew they were breaking the rules they had collectively designed and enforced on the country. The emails show No. 10 staff asked to hide wine bottles from the cameras – then joked that they seemed to have ‘got away with’ drinks parties that broke the law.

But in the end, they did not get away with it. The Prime Minister remains guilty – most explicitly of misleading the House of Commons when he denied that any parties took place. He has shown a serious failure, too, in not learning from his mistakes. It is no use him or anyone else in government complaining about the triviality of the charges. His government put the lockdown laws on the statute book in the first place, framing them in such a way as to criminalise everyday interactions.

Now the Prime Minister’s allies plead for clemency. It is in human nature, they say, to gather to bid farewell to a departing friend or colleague, to offer friendship and succour. Quite so. Johnson’s allies further argue that, as he raised his glass in a toast, he did so in a work capacity – as evidenced by the presence of his red box. This Jesuitical defence would be more plausible if the government’s laws had not seen ordinary people dragged to court and found guilty of far milder offences. Let us consider his defence for the leaving party:

I briefly attended such gatherings to thank them for their service – which I believe is one of the essential duties of leadership. Particularly important when people need to feel that their contributions had been appreciated and to keep morale as high as possible.

It is a damning – and accurate – charge against the Prime Minister that he is no man of principle

Does he realise, even now, that he made it illegal for anyone to do this during lockdown? Where, in his lockdown rules, was the exemption for the ‘essential duties of leadership?’ Where was the clause allowing those outside the ruling elite to have a regular ‘wine-time Friday?’ Does he realise that he personally used the powers of his office to send the police after anyone else who would have attended a gathering to salute a departing colleague? Or, for that matter, to console a friend, visit a dying relative or even attend a funeral in numbers greater than stipulated by the staff of No. 10.

The Prime Minister said it was ‘right’ to salute former colleagues in a leaving party. He’s quite correct in that it is a decent, humane thing to do. But consider the childminder in Manchester who was fined for delivering a birthday card to a child in her care: was it ‘right’ for her to do so? Of course. Did this help her, when police intercepted her to enforce the Prime Minister’s rules and took her to court? Not one bit. His needless, draconian lockdown rules were enforced by police upon millions of people, with tens of thousands taken to court. No one – not the pensioner in his allotment, not the mother celebrating her child’s birthday with two friends – had the chance to argue before the magistrates that what they were doing was ‘right’.

When police went after two women in Derbyshire for the crime of walking through a park with takeaway coffee, one might also ask: was it ‘right’ for them to seek each other’s company and avail themselves of the basic liberty of a free country? Of course. Did Johnson’s laws prohibit this? Unforgivably: yes. And this is the point.

So to hear him now talk about what was ‘right’ and ‘decent’ is hard to swallow. This magazine argued for him to decriminalise lockdown rules, to offer guidance and leave people to judge what is ‘right’ – as was being done with much success in Sweden and several states of America. But Johnson refused to do so, preferring to turn Britain into a police state. While having every intention of flouting the laws when he considered it opportune to do so.

How ironic that in the November 2020 photograph of Boris Johnson raising a toast to the spin doctor he had forced to resign, a copy of The Spectator can be seen resting on the table. This magazine had argued against that month’s lockdown and its needless criminalisation of everyday life. By then, the logic for lockdowns had collapsed. But, thanks in part to a supine opposition, No. 10 pressed ahead anyway. Those leaving drinks took place when all other social gatherings had been banned under pain of huge fines.

Lockdowns involved the passing of the most damaging, illiberal laws in British postwar history. The social and economic cost is still being counted. Johnson is guilty not simply of breaking his own rules, but of failing to assess if those rules even worked. The sheer scale of the law demanded a rigorous assessment of the policies behind it, but no serious cost-benefit analysis was conducted. Nor were studies commissioned to ask why infections seemed to have peaked before the previous lockdown. And no one is now asking why, if lockdown was the only means of holding back a Covid wave, Sweden has done so well without ever imposing one.

The Prime Minister has not been ‘vindicated’ as he claims. No one who spent months trying to abide by his lockdown laws is under any doubt of what went on. He is guilty of presiding over a gung-ho culture in which lockdown advocates were never properly challenged. He allowed himself to be bounced into taking deeply damaging decisions. His own instinct to resist lockdown was not enough: he could have assembled ‘red-team’ advisers to challenge Sage. He could have asked the Treasury for a cost-benefit analysis of lockdown. He could have made the second lockdown a matter of guidance, not of law. Instead he closed society down over and over again, asking his aides to implement laws they themselves regularly flouted.

Johnson has further opened himself to charges of hypocrisy through his confected fury about his former spokeswoman Allegra Stratton, who resigned after being caught on camera making light of the parties that were being held in No. 10. There is no suggestion that she broke any rules. She was poking fun at the absurdity of the law and of being asked to defend such a ridiculous situation.

Her laughter, Johnson declared, had caused national anger – an anger that he said he shared. He was shocked – shocked! – to find any such behaviour was happening in No. 10. Stratton resigned on principle, the only person in No. 10 to have done so.

It is a damning – and accurate – charge against the Prime Minister that he is no man of principle. Weakness in personal conduct need not necessarily make a bad prime minister – Johnson’s hero Winston Churchill drank to excess for most of the second world war. The important part of leadership is getting the big decisions right. Johnson is often said to be a leader who manages to do just that – and certainly on Ukraine that claim can reasonably be made. But on Covid and lockdowns (and, recently, tax rises) he got some big decisions very wrong. His predicament over partygate is testament to that.

His failure to be guided by his instinctive liberalism has led him to the worst and most avoidable disasters of his premiership. He can still learn from these mistakes. But we are more than halfway through this parliament: he does not have much time left.

How to mend (almost) anything

‘Sides to middle’, that’s the cry. When your foot goes through the flat sheet in the night, there’s only one thing for it: scissors down the centre, then sew it edge to edge. Good as new – for as long as your stitches hold up. If you’ve paid for Egyptian cotton, you cannot cut your linen into dusters the minute the thread count wears thin.

Besides, call it eco-activism, call it penny–pinching, mending things is fun. From time to time, when my husband is washing up, a plate will crumble like a biscuit in his hands. Seeing his ‘it wasn’t me’ expression, I’ll tell him that the plate, glued and glued again, was beyond salvation. Then I’ll glue it together again. My mum saves her shards believing I have some magic Bostik touch. I don’t. But I’m patient and I’ve always liked jigsaws. (Top tip: keep a bottle of nail-polish remover handy. Best thing for ungluing fingers from thumbs.)

Japanese potters practice kintsugi, repairing broken pots with gold dust and lacquer. Then there’s sashiko – visible mending – dodgy needlework raised to an art. I’m a lousy seamstress (buttons stay on if you don’t tug too hard) so I take trickier tears to Moses, who works at the local dry cleaners. A man aptly named: he parts the seams and draws them together again. Find your own Moses. They’re worth their weight in lacquered gold.

Shoes go to Distinctive Shoe Repairs on Norfolk Street near Paddington station, open since 1951. Boots are re-soled, kittens re-heeled, belts punched with new holes. Jokes are on offer: ‘I’m no vicar, but I can certainly heal your sole.’ When I took a vintage Louis Vuitton bag, bought by my mum in the power–dressing 1980s, to the LV concession in Selfridges, the manageress looked at me like a cat that had brought in a uniquely mangled mouse. Yes, they did repairs, but this… I took it to Norfolk Street, where, bang, bang, stitch, the strap was repaired. Saddlers are good for clasps, buckles and battered suitcases.

There’s a man called Graham in West Lothian who fixes GHD products. When my hairdryer started smoking last summer – I love the smell of burnt hair in the morning – I put it in a Jiffy bag and sent it first-class to Graham, who fixed it in a day and sent it back. All for £33.95. A new GHD blower is £119.99 and the old one would have gone to landfill. I’ve just dispatched my Roberts Revival radio, transmitting only Static FM, to the Roberts repair shop. There are, however, limits. I will not sit darning M&S multi-pack socks by the fire.

‘Right to repair’ is a serious issue. I hate having to give up on yet another pair of headphones/blender/all-in-one-printer-scanner-pain-in-the-neck. Earlier this year, I tried to get my warhorse printer repaired. The call-out charge was £69 +VAT, more than the cost of the thing in the first place. The replacement part would have cost some hundred pounds more. I bought a new model and took the old one to the electrical recycling bin. Somewhere, a fairy died. It was the same with the washing machine. Two engineers, two ruinous credit-card payments and the advice: ‘Better get a new one, love.’ When this one blows, I’m buying a copper and an old-fashioned mangle.

Spectator competition winners: sonnets on Mammon

In Competition No. 3250, you were invited to submit a sonnet to Mammon.

It was ‘Epigram for Wall Street’, attributed to the oft-impoverished Edgar Allan Poe, that prompted me to set this moolah-themed challenge. In a large, thoughtful and winningly varied entry, there were echoes ranging from Keats, Milton and Barrett Browning to Gordon Gekko.

Katie Mallett, Janine Beacham, George Simmers, David Silverman, Bob Trewin and Ralph Bateman earn honourable mentions. The winners, printed below, pocket £20 each.

Mammon, I love you. Let me count the ways, Although that’s strictly my accountant’s chore. I live delights and scorn laborious days Thanks to my wealth, while hungering for more. I build portfolios, by love possessed. Such words as ‘leverage’ are holy writ. Lucre is never filthy. Greed is blessed. The rapture, the divine romance of it! I love you as an oligarch loves yachts, Or Texans love a gushing oil well. I love you as I love those ritzy spots That cater to a upscale clientele Swimming in loot, dinero, wonga, dosh. As for the poor, ‘qu’ils mangent de la brioche’. Basil Ransome-Davies

Getting and spending, we find riches good, For purse strings are with heartstrings intertwined. Unjustly is the golden calf maligned; When we feel moved to strive for wealth, we should. ‘It’s evil to love money!’ That falsehood (In every schoolchild’s adage hoard enshrined), Has, by misguiding many a youthful mind, Left capital’s romance misunderstood. Commerce has built up nations, science, art. The ground and bulwark of our lives is money. No disposition would for long stay sunny If our financial system fell apart. Despite the grim knell socialists have tolled, We quite like travel in the realms of gold. Chris O’Carroll

A god thou art that stands beyond compare, That claims no truth, that issues no commands; Lacks holy writ and calls no one to prayer, Holds out high hopes yet makes no strict demands. Thy spirit works within the human core Where dread of want once helped the racesurvive: That fear turns now to wanting ever more, For with thy faith to covet is to thrive. A tithe of all such gains, both small and great, Is owed to thee to celebrate and bless: Its quantum is not hard to calculate, Since what it constitutes is all excess. What we pursue or take beyond our need We lay before thee in the name of greed. W.J. Webster

Much have I travelled round in search of gold And many an empty rainbow’s end I’ve seen; In countless cruel casinos I have been Hoping to have a win of wealth untold. But fortune never came; however bold My bids to be as wealthy as the Queen, My greatest efforts left me poor and lean Till Mammon lost its lustre and its hold. Then felt I like a sinner freed from sin Washed clean of lust and longing for excess, And fate at last no longer seemed unfair. Contentment with my lot counts as a win And now when life awards some small success I feel I have become a billionaire. Frank McDonald

The avaricious race on vicious loops; The more they get, the more they fret for loot – Yet if their income droops, like nincompoops They feel oppressed and think they’re destitute. Though Adam Smith dispelled the myth that lust For heaps of pelf is in itself a sin, When grabby heirs of billionaires go bust We’re not devoid of schadenfreude’s grin. Rapacity’s capacity is vast; It’s everywhere that laissez-faire exists. You think you’ve got it vanquished? Not so fast; Cupidity’s stupidity persists. And so a poet pens inchoate bosh In hopes his wit will bag a bit of dosh. Alex Steelsmith

Mammon is at Cambridge too, although I never see him sweating in the stacks. He’s not so energetic as to row, but prowls in punts for hours along the Backs. He sears a swath through every May Week ball: gorges on oysters and champagne till dawn, rampages round the silent-disco hall, then pukes kaleidoscopes on Fellows’ Lawn. It somehow never seems to make him fatter. Mammon always gets the pretty girl though she looks dazed and teary in the morning. He’ll scrape a third. It doesn’t even matter. He bridles at the mildest hint of warning. Mammon knows how soon he’ll rule the world. Mary McLean

When I consider how my loot is spent the boomers make an oligarch look cheap: we maxed the gilts out so the debt’s waist-deep, and scraped the barrel clean in Brae and Brent. We bought the houses up and charge you rent our ops-and-drugs bill makes its annual creep; a gold-plate pension would make Midas weep, and now inflation’s touching ten per cent. The post-war babies had a Mammon tree with double Miras off the mortgage rate; our parents’ lolly came to us tax-free – we sent their care bill to the nanny state; the feckless and the work-shy old agree: we all deserve who only stand and wait. Nick MacKinnon

No. 3253: me time

You are invited to provide a poem entitled ‘Song of Myself’ in the style of a well-known writer. Please email entries of up to 16 lines to lucy@spectator.co.uk by midday on 8 June.

2557: Heroes

Clockwise round the grid from a point to be determined run the names of four knights (2,5,5,5,5,8,5,3) followed by what they are (two words). A clued light tells how many 35 they have amassed between them, while a pair of unclued lights indicate a 17 linking all four.

Across

8 Wearing medal one accepted (5)

9 Estate in Albania attracting hatred (7)

10 Into toads? Wrong – I’m into dragonflies (9)

12 Gosh, old Oscar gains medal! (4)

14 Girl runs in sandals (5)

15 Novelist in court getting large fine (5)

16 Fourth man to mount horse (4)

20 Island graduate arrived in (5)

24 Pigeon avoids master gardener (4)

25 Heartless fanatical attack (4)

27 Grunter doesn’t start row (3)

28 Not very excellent bank (4)

30 Rounds of gammon (4)

31 Some queans give birth to poet (3)

32 Sorrow due to cycling (4)

33 See hard stone and rough rock (4)

34 Plump tenor after work (3)

37 Sound of dated plane (4)

39 Jack Absolute and Scarlett’s place (4)

40 Germ’s right inside medicine bottle (5)

41 Rake imbibes good French wine (5)

43 A singer amorously engaged (4, two words)

44 Line in score duo added (9, hyphened)

45 Townsman visits honest relation (7)

46 Brilliant poem’s inside writer (5)

Down

1 Where to go that’s beset by dashing men (6)

2 Merry goey poet’s past (4)

4 Within Antrim upset maiden hid (5)

5 Empty street crossed by sad Scots (5)

6 No yawner goes off like Fortinbras (8)

7 Phantom fish in Spain worried loon (7)

11 Onan’s wife accepted old buffalo (7)

13 Most crafty son changing style (6)

18 Seaman stripped bare (3)

19 Scrap involving female rural dean (5)

21 Old gun held by one old gnome (5)

22 Tomboy pictures abatis (7)

26 Skilful mediator worked without me (6)

27 Bone of swab (deceased) (8)

29 Fancy better grass (7)

31 I say nothing (3)

36 Bishop propels boat over English surf (6)

37 Pig the French pull by the ears (5)

38 Lass a long time cuddling knight (5)

39 As far as that shrub (5)

42 East-ender’s weapon (4)

A first prize of £30 for the first correct solution opened on 13 June. There are two runners-up prizes of £20. Please scan or photograph entries and email them (including the crossword number in the subject field) to crosswords@spectator.co.uk. We will accept postal entries again at some point.

Download a printable version here.

The Battle for Britain | 28 May 2022

Claude Vivier ought to be a modern classic. Why isn’t he?

April is the cruellest month, but May is shaping up quite pleasantly and the daylight streamed in through the east window of St Martin-in-the-Fields at the start of I Fagiolini’s latest concept-concert, Re-Wilding The Waste Land. The centenary of Eliot’s poem is the obvious hook. But whether you’re counting from the Rite of Spring riot in 1913, Schoenberg’s Skandalkonzert the same year, or further back to Strauss’s Salome or Debussy’s Faune, music’s modernist moment occurred some time earlier. Which is helpful, in a way, because it freed the group’s director Robert Hollingworth from the limitations of chronological programming and gave him scope to do something a bit more interesting, and possibly a bit more Eliot-esque.

So the programme – all of it for an a capella line-up of seven or fewer singers – had one foot in the 16th century and another in the 21st, with a couple of brief nods to the 20th. Vaughan Williams’s Silence and Music sounded like sirens in the mist, and Kenneth Leighton’s God’s Grandeur brushed Gerard Manley Hopkins into the mix to play off Eliot’s own contrapuntal chorus of allusions and verbal registers. Tamsin Greig read, or, to put it more accurately, performed passages of The Waste Land between the musical numbers (she do the police in different voices), and we were asked not to applaud until the very end. The idea of creating a seamless 70-minute meditation on the poem’s themes worked well in the atmosphere of the slowly darkening church, and would have worked better if Hollingworth hadn’t intervened with donnish, well-intentioned introductions to the individual sections.

But the central concept was strong, using Eliot as the pivot point between the sombre ecstasies of Victoria’s Tenebrae Responsories and a series of new commissions by Joanna Marsh (bright, sometimes skittish settings of Pattiann Rogers and John F. Deane), Shruthi Rajasekar (perfumed tone-painting, complete with vocal tabla effects) and – most effective of all – Ben Rowarth, whose sonorous choral gestures, sputtered vocalisations and decaying microtonal harmonies exuded an eerie, very Waste Land-ish bioluminescence. Coming after Victoria, a Byrd psalm-setting rang and chimed (I Fagiolini’s men can bite without aggression, just as the female voices glow without any loss of clarity). Both Greig and the singers placed their phrases plainly, but unerringly, into the silence, while the sounds of Charing Cross anno 2022 – police cars, buses, bursts of pop music – buzzed very faintly through leaded glass. These fragments I have shored against my ruins; anyway, you get the picture.

Across the Thames, the London Sinfonietta presented a short but imaginative celebration of Claude Vivier, the Canadian composer who – as Paul Griffiths explained in the programme – was found dead in his Paris apartment in 1983 with 45 knife wounds in his body. Griffith’s extensive biographical essay (he’s one of the few current writers who treats programme notes as art) was typical of the care that the Sinfonietta had lavished on this brief concert, which played to a two-thirds full Queen Elizabeth Hall, and whose one misjudgment was the première of The Seeds of Solitude by Nicole Lizée, a brilliantly scored commission that never really transcended its role as soundtrack to a triptych of whimsical short films.

The composer Claude Vivier was found dead in his Paris apartment with 45 knife wounds in his body

Well, heaven knows we need more composers with a sense of humour. It just felt like the wrong moment to pull focus from Vivier, whose music sprang to life with all the immediacy of what was clearly an outsize artistic personality. Lonely Child combines the surface simplicity of Hans Abrahamsen’s Let me tell you with the inner fury of George Crumb, and Claire Booth sang with an artlessness that suggested anything but innocence. Zipangu is a strapping, juicy-crunchy workout in post-Penderecki string sonority that should really, by now, be popping up on movie soundtracks and in the programmes of ambitious youth orchestras. Ilan Volkov, conducting, eats scores of this complexity for brunch: Vivier ought to be a modern classic and nothing I saw or heard at the Southbank got me any closer to understanding why he isn’t.

For a booster shot of cultural optimism there’s always Sheffield, where the resident Ensemble 360 launched its first post-plague Chamber Music Festival in the bearpit-like Crucible Studio. With the audience on all sides, the musicians have no choice but to be upfront. Kathy Gowers (violin) and Rachel Roberts (viola) made Martinu’s fiendish Three Madrigals sound like the most fun two string players could have together, before the whole ensemble coalesced around pianist Tim Horton for a performance of Dvorak’s Piano Quintet that felt like one big smile. And packed all around, silently urging them on, was an audience whose youth and diversity outstripped the most fevered imaginings of an Arts Council equality commissar. Elgar said it first, and he wasn’t entirely joking: ‘The living centre of music in Great Britain is not London, but somewhere further north.’

The cruelty of reality TV was part of the appeal

Jade Goody appeared on Big Brother in 2002. She was a short, loud, blonde-haired woman who broadcast her every thought and feeling, either in her thick Cockney accent or with her unforgettable face. She became a star. In 2007 she appeared on Celebrity Big Brother, where she made racist comments about her fellow contestant, the Bollywood actress Shilpa Shetty. Effigies of Goody were burned in India; the Sun called her ‘the face of hate’. Hoping to redeem herself, she agreed to appear on Indian Big Brother, where she was told she had cervical cancer with the cameras still rolling. She died less than nine months later.

It was a three-act drama that only reality TV could have delivered. Call it 45 minutes of fame. Goody was difficult, abrasive and naive, with an effortless talent for being herself. She had the quality that Sirin Kale and Pandora Sykes, in their new podcast Unreal, identify as the key to reality TV success: authenticity.

On reality TV, they argue, viewers could tolerate people from very surprising walks of life – gay people, trans people, people with disabilities – choosing winners who were, as the misleading saying goes, ‘ahead of their time’. But if there was a difference between who you were and how you acted, if they could sense a calculation taking place between what you thought and what you did, you were finished. This preference for immediate, legible personalities meant that reality TV produced its own first premises as a criterion of success: what viewers wanted from their TV playpeople was for them to be ‘real’.

Watching Simon Cowell breathe Novichok at wobbly teens never felt normal or guiltless

They were already real, of course, hence the moral quandary that animates Unreal: A Critical History of Reality Television, a new ten-part series on BBC Sounds. Namely, it is fun to watch people sing terribly and take a verbal whipping from Simon Cowell, but it’s hard to avoid the fact that you are being entertained by someone’s public humiliation.

Kale and Sykes argue throughout the show that the change in social attitudes over the past 15 years means much of this material hasn’t ‘aged well’. What sort of material do they mean? Shows such as There’s Something about Miriam, in which the bachelorette is ‘revealed’ to be a trans woman. Trinny and Susannah ripping off women’s tights in public. Extreme makeover shows like The Swan, where women were turned into Stepford contestants, nipped and tucked out of all recognition.

Reality TV wasn’t above contrivance: if the women in The Swan didn’t cry with joy at the big reveal scene, the show’s producers would ask them to hold their hands to their mouths instead. As for Big Brother, it was half game show, half Stanford Prison Experiment. As the seasons went on, the producers began making the house physically smaller to increase the sense of claustrophobia. ‘We had a theory,’ remembers producer Phil Edgar Jones, ‘that things were always funnier if people were arguing in fancy dress.’

All this comes pouring out of what must have been months of research, and Unreal impressed me with how elegantly it condensed its material. It’s a bouncy piece of inside baseball, one that will interest anyone who was (regrettably) conscious in Britain between 2000 and 2010. I’m just not quite convinced by its argument.

Looking back, Kale and Sykes say they now feel uncomfortable with a lot of what they were watching. The show’s thesis pivots grindingly about a ‘but’: reality TV is an important part of our culture, but we can enjoy it while thinking critically about the ethics behind it. Maybe I’m missing something, but wasn’t the wickedness part of the appeal – not just because it was exciting, but because it was so obviously cruel?

Watching Cowell breathe Novichok at wobbly teens never felt normal or guiltless. It never felt like simple fun. It was something you could or couldn’t bring yourself to watch. Or perhaps couldn’t admit you enjoyed. Or even gleefully bragged about enjoying. Like most sweeping cultural events, reality TV evoked a regular cast of strong responses that different viewers could lay claim to. Kale and Sykes suggest that these shows are great fun but they’re unethical. Where Kale and Sykes have a ‘but’, I would have a ‘because’. These shows were always hard to watch, and like a great many iconic human entertainments, they enjoined the viewer to play chicken with his or her own conscience. This was itself an essential part of their entertainment value. I sometimes think about this when I see photos of the Roman Colosseum.