-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Penny Mordaunt doesn’t understand the internet

Penny Mordaunt’s flip-flopping over gender self-ID makes it difficult to know where she stands. But on another issue she has made things abundantly clear: Mordaunt doesn’t understand how the internet works. If she makes it to the final round of the leadership contest this afternoon – and indeed to No. 10 – Mordaunt has vowed to make the likes of Facebook and Google pay when news content appears on their sites. This half-baked plan makes a fundamental misunderstanding. Mordaunt says:

‘We will create a news bargaining code, similar to the law that has been passed by the Australian government. This will mean that major online platforms like Google and Facebook will be required to reach a deal with news publishers to compensate them for their content being freely distributed across those services.’

By ‘freely distributed’, Mordaunt appears to be referring to links to news stories. But why should Facebook and Google cough up for this? Here’s a link to the article Mordaunt wrote in City AM setting out this proposal. Should The Spectator have to fork out for including it in this piece? Of course not – so why should Facebook? Nick Clegg and Mark Zuckerberg might be deeply unlikeable individuals but that doesn’t mean we should single out Facebook for special treatment.

The truth is that websites like Facebook and Google drive people to news sites, not the other way around. When a link to a news story appears on Facebook, if it’s interesting enough, people will click on it and arrive on a different website. Is Mordaunt really suggesting Facebook, rather than the newspaper, should pay for this privilege?

Mordaunt makes another rookie mistake here

In the short term, this policy looks like a win-win for news websites. But the truth is that by forcing Facebook to pay out every time someone clicks on a news link, it will backfire badly. A leaked memo reported by the Wall Street Journal yesterday reveals that Facebook is ‘reallocating resources from its Facebook News tab…as the company focuses more on the creator economy’. The paper also says:

‘Facebook’s shift away from its paid news product was influenced by the stepping up of regulation around the world aiming to require technology platforms such as Facebook to pay for news’.

When frontline politicians like Mordaunt come up with nonsensical plans like this one, it’s hard to blame Facebook and Zuckerberg for wanting to change tack.

Facebook is terrified by the rise of TikTok and its short viral videos designed to grab attention. TikTok’s success comes from two things: its content is made by people who intend to distribute it almost solely on TikTok; and its algorithm, which keeps people hooked by showing them more of what they like, and less of what they don’t.

As a result of this threat, Facebook is now playing catch-up. In the past, its strategy has been to buy out a competitor, as it did with Instagram (for $1 billion (£800m) in 2012) and WhatsApp (for $19bn (£11.4bn) in 2014). It’s too late to do that with TikTok, whose value dwarfs that of those companies. And even if Zuckerberg were to open his wallet, TikTok is owned by ByteDance, a Chinese multinational headquartered in Beijing. Such an acquisition would mean Zuckerberg makes himself even more unpopular that he already is in Washington DC and London with politicians worried about China.

So the choice for Facebook is to change the way it operates. As a result, it has given its news feed a radical shake-up in recent weeks. Viral videos – which keep people on Facebook and keep people scrolling – are now featuring more prominently than your auntie Doris’s post about her missing cat. It doesn’t take much to guess what is also appearing less: links to news articles that take people away from Facebook. Facebook is coming to realise – too late perhaps – that such links aren’t what many younger users want to see. Even those people who do want to see them can end up gravitating away from Facebook and ending up on another site.

So Mordaunt’s proposed scheme is not only backhanded, it comes far too late: her idea was designed for an internet that has changed. Worryingly, Mordaunt also shows she doesn’t understand how free markets work. She says:

‘Free markets only work if they are fair markets, and that’s why as Prime Minister I will bring forward the government’s proposed competition legislation which will empower the new Digital Markets Unit. This will help ensure fair dealing for smaller businesses that have to use services like Google, Amazon and Facebook to reach their customers.’

Mordaunt makes another rookie mistake here: none of these smaller businesses have to use Facebook or Google. They do so because they’re good for businesses. Many small – and indeed big – businesses advertise their wares on Facebook because they know it works. Others use Google because it helps customers find them. And businesses use Amazon because they want to use its distribution network, or to gain access to an enormous pool of customers. But Mordaunt seems to be suggesting these companies should be punished for their success. They shouldn’t.

Of course, all this would be bad enough on its own. But Mordaunt also wants to police the internet through the Online Safety Bill. She insists that, if in a position to bring this into law, she will get the balance right between free speech and cracking down on ‘harmful’ content. But why should we trust someone like Mordaunt when she has shown all too clearly that she doesn’t understand the internet?

Boris Johnson’s final PMQs was a let down

Boris Johnson’s farewell Prime Minister’s Questions was rather like his premiership: full of the unexpected, rather chaotic and a bit of a let down. Westminster has already visibly moved on from Johnson, even though he remains in office until early September, and so Keir Starmer devoted his questions to asking Johnson about the candidates to be his successor.

Johnson claimed that he wasn’t following the contest particularly closely, but that any one of the candidates would, ‘like some household detergent, wipe the floor with him’. Starmer, however, was enjoying the many insults that have been thrown between the camps in this race to be leader, and quoted a number of them back at the Prime Minister. His theme was that no-one in the party was now proud of what it stood for or what it had done in government:

Tory MPs rose into a standing ovation for the man they were calling on to quit from the same benches two weeks ago

‘They’ve trashed every part of their record in government, from dental care to ambulance waiting times to the highest taxes in 70 years. What message does it send when the candidates to be prime minister can’t find a single decent thing to say about him, about each other, or about their record in government?’

Starmer used each question to deal with a different candidate. He asked whether Johnson agreed with Rishi Sunak that the plans of his opponents were ‘fantasy economics’; or whether Liz Truss was right that Sunak had no plan for growth. Then he pointed out that Penny Mordaunt had said ‘our public services are in a desperate state, we can’t continue with what we’ve been doing because it clearly isn’t working’, and asked: ‘Who’s been running our public services for the last 12 years?’

He also quoted Kemi Badenoch’s claim that she had warned Sunak that the covid loan scheme was at risk of fraudulent activity, and that he had ignored her. There was plenty to be going on, which will underline to the Conservatives the risks of having so many arguments in public.

Johnson ignored most of these questions about the people who are the future of the party, and tried instead to underline what he thought was his legacy in terms of getting the calls right on the pandemic, standing by Ukraine and the legacy of the last Labour government. He stuck to his ‘Captain Hindsight’ moniker for Starmer, also calling him a ‘pointless, plastic bollard’. The Labour leader’s memorable line was that Johnson had ‘decided to come down from his gold wallpapered bunker for one last time’.

Tory MPs were in strong attendance, and looked relaxed as they watched the man they’d tipped out of office say his farewell answers. For months they have grown steadily more miserable to the point of remaining motionless with horror during some of the worst PMQs. It was, then, quite striking to note that the most depressed-looking members of the chamber now are those sitting on the SNP benches behind Ian Blackford, who is still battling his way through his own internal party scandal and who once again asked two rather poor questions.

The session went on rather longer than usual. It culminated with a question from Sir Edward Leigh, a Johnson supporter, who channelled Churchill’s anaphora in an unintentionally amusing manner to list the Prime Minister’s achievements and thank him ‘on behalf’ of the many people he had helped. Johnson replied that he would use his last few seconds to give some advice to ‘my successor, whoever he or she may be’. That was to ‘stay close to the Americans, stick up for the Ukrainians, stick up for freedom, for democracy everywhere, cut taxes and deregulate whenever you can’.

He then had a strange non sequitur which underlined how much he hopes that the next leader is not Rishi Sunak, turning to criticise the Treasury and claiming that ‘if you always listen to the Treasury, you wouldn’t have built the M25 or the Channel Tunnel’.

His achievements, he said, were getting the biggest Tory majority for 40 years; using Brexit to have ‘transformed our democracy and restored our national independence’; taken the country through the pandemic; and ‘saved another country from barbarism’. That last point on Ukraine feels a little premature, but Johnson said that seemed to be enough to be going on with.

‘Mission largely accomplished, for now’, he said, slightly threateningly, before finishing on ‘hasta la vista, baby’. Tory MPs rose into a standing ovation for the man they were calling on to quit from the same benches two weeks ago. And then they went off to vote for the person who’ll replace him in what Johnson at least regards as unfinished business. He might as well have said another Arnie quote: ‘I’ll be back.’

Another Mordaunt Twitter blunder

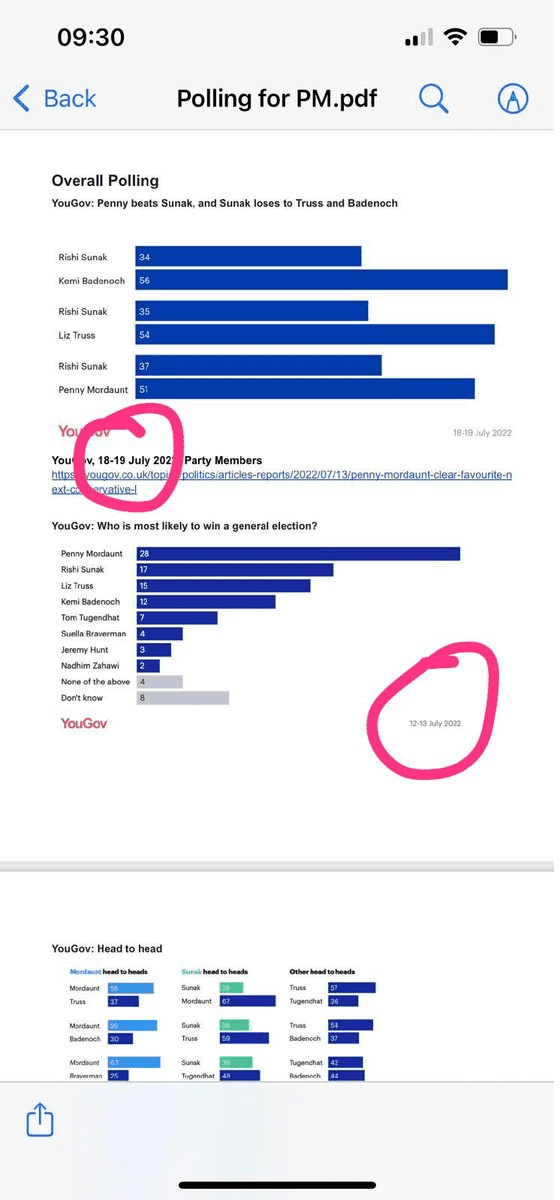

Oh dear. It seems that the Mordaunt camp has done it again. Just hours after suggesting that Rishi Sunak or Liz Truss would ‘murder’ the Tory party if they were elected, another suspect #PM4PM tweet has been doing the rounds. It’s about the Trade minister’s ability to win a general election, citing a YouGov poll of 18-19 July of Tory party members. Team Mordaunt has released a graphic which shows Penny on 28 points compared to Sunak and Truss on 17 and 15 respectively.

Separately, screenshots of a document are also being shared among MPs by Mordaunt’s supporters, again referring to the YouGov poll labelled 18-19 July. Unfortunately, that poll was actually conducted between 12-13 July, as YouGov’s findings show here. That polling was done before the controversies of the past week as Penny Mordaunt’s views have come under increasing scrutiny, with a corresponding dip in her favourability among members. Yesterday’s survey actually showed Mordaunt losing to Truss, and with a slimmer lead over Sunak.

The screenshot of the document being circulated to MPs shows a timestamp of 9:30 a.m and the time of the tweet was 10:01 a.m. Was team Penny aware of the inaccuracy? Or did they decide to tweet the graphic anyway? Either way, after recent doubts about their candidate’s mastery of a brief, good to see Team Mordaunt showing their candidate is across all the detail…

Watch: Boris signs off at PMQs

It was Boris Johnson’s final time at the despatch box today but there was little sign of it from some of the contributions. Scratchy, verbose, partisan: and that was just the Labour MPs. Still, that didn’t faze the outgoing PM who, to rapturous applause and cheers from his benches, told the House about ‘some words of advice to his successor.’

He told either Rishi Sunak, Penny Mordaunt or Liz Truss to ‘stay close to the Americans’ (an obvious reference to Churchill) and to do the same for the Ukrainians, plus cut taxes and deregulate ‘to make this the greatest place to live and invest in.’ He ended with a pointed jibe at those ever-online MPs whom he feels forced him out of office by focusing too much on social media, saying ‘above all, it’s not Twitter that counts.’

He then left the House of Commons to a standing ovation from Tory MPs. Labour, unsurprisingly, did not join in. Magnanimous to the last eh?

The impossibility of separating Scotland from Britain

Most histories of the United Kingdom fail to account for, or even acknowledge, just how unusual a country it is. One of the strengths of a history of Scotland within the United Kingdom is that it cannot avoid emphasising the sheer strangeness of Britain. It is a country quite unlike other European nations for it is, at heart, a composite state: a Union of four other nations creating a fifth which exists alongside – and sometimes above – its constituent parts.

The tensions and interplay between these identities form part of Murray Pittock’s handsome new history. Although titled a ‘global history’ of Scotland, it is also, inescapably, a history of Britain itself, albeit one written from an ultra-northern perspective. Britain, he suggests, is the last surviving true ‘composite monarchy’ in Europe. All the others – the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes – have come and gone. Only Spain – which ‘no longer in practice considers itself to be a composite monarchy’, whatever the Catalans might argue – rivals the United Kingdom as a multi-national union state.

The irony of today’s nationalist dominance in Scotland is that it is made possible by the successes of its Unionist forebears. Scottish Unionism has always been nationalist too, insisting that Scottish privileges, and Scottish distinctiveness, be maintained. The survival of Scotland as an idea – and hence as a political possibility – is a Unionist achievement from which the SNP now benefits. Scotland’s double identity – always Scots but British too, even if not always enthusiastically – is the core of Pittock’s history. Even when unchallenged, Union has often been a bittersweet experience. The Scots Magazine, founded in 1739, lamented that ‘in many things calculated for the good of Great Britain, Scotland is little more than nominally consider’d’. The 19th-century cults of William Wallace and Robert Burns were not accompanied by a demand for statehood but they expressed a familiar yearning for Scottish distinctiveness to be recognised.

Today’s nationalist dominance is, ironically, made possible by the successes of its Unionist forebears

For, to borrow from Pierre Trudeau, Scotland shares a bed with an elephant. Union of the Crowns in 1603 was a reverse takeover of a kind, partially overturned by formal Union in 1707. Since then, Scotland has existed as a stateless nation even as it played a disproportionate part in the building of a new one: Britain.

At the end of the 17th century, England’s population was about four million and Scotland’s one. An under-appreciated contributing factor to Britain’s current political instability is that the ratio of English to Scots has over the centuries grown from 4:1 to the current 11:1. Scotland has become a smaller part of Britain even as, in many respects, Scotland and England have grown ever more alike. Voting SNP is not just a matter of political enthusiasm, it is a statement of cultural distinction too. Union, perhaps, but not uniformity.

As Pittock notes: ‘Scotland after the Union was to remain a state within a state, but with this important addition: Scots could now engage as equals in domestic British and – more importantly – international imperial markets.’ The debit side of this bargain was ‘the loss of political (though not institutional) autonomy’. In 1707, ‘Opponents of Union dwarfed its supporters in numbers, though not to quite the same extent in influence’. The defeat of Jacobite risings in 1715 and, once and for all, in 1745 opened the path to a new Scotland and a greater Britain. Scotland would become British without ceasing to be Scotland. And, above all else, there was opportunity on a global scale. By the latter part of the 18th century, half the whites in Jamaica and 80 per cent of those in Antigua were Scots. Most of these were from middling backgrounds who lacked opportunity at home but could take advantage of the powerful networking effect of Scots abroad: ‘Scots Masonic lodges were founded in the Caribbean to establish, reiterate, and accelerate networking, and even a branch of the Fife sex club, The Beggar’s Benison, was established in Grenada,’ writes Pittock.

In India, where in 1780 half the writers appointed to the East India Company were Scots, it was sometimes complained, as Pittock discovered, that: ‘No man of any other nation can serve and survive in an Indian province, where the Chief is a Scot and where there is a Scot to be found.’ India, as Sir Walter Scott put it, was ‘the corn chest for Scotland, where we poor gentry must send our youngest sons as we send our black cattle to the South’. It was never the ‘English Empire’. Indeed, Sir Charles Dilke, the ‘radical Liberal statesman’, suggested in 1868 – tongue partly in cheek, perhaps – that given the disproportionate role of Scots in the Empire: ‘It is strange, indeed, that Scotland has not become the popular name for the United Kingdom.’

The 19th century was Scotland’s age of glory because it was also Britain’s preeminent era. By the middle of the century the Scottish economy had overtaken that of England and Wales in per capita terms. By comparison, the 20th century, whatever its saving graces and improvements, was a period of decline.

If this was relative in real terms, it was absolute if measured on a psychological level. And since Britain was Scotland’s handmaiden of opportunity, British decline consequently altered the terms upon which Scots engaged with Britain. Today’s Scottish nationalism is a response to British decline and retreat; for many – though far from all – the Union is viewed in purely transactional terms. ‘It was to be no coincidence that the decade the British Empire ended was the first decade in which Scottish nationalism achieved significant support,’ Pittock declares.

If that is, perhaps, a little too neat, it is also not entirely wrong. At the same time, Scots could be impeccably British – or even English – overseas but this did not require them to embrace the idea of a wholly integrated Union at home. Even as late as the 1920s and 1930s, Scots considered the imperial project a partnership. My own grandfather left Aberdeenshire for the Malayan rubber plantations for the same reasons as so many Scots before him, and to take advantage of the same networked connections available to Scots on the make; on the other side of the family, my great-grandfather was a bookseller to trade in India.

The Empire is now unfashionable, but even today the sense in Scotland that the Empire was not entirely kosher jostles with a vestigial satisfaction that if there was to be an Empire anyway, at least let it be a largely Scottish one. Nor was it just a matter of overseas adventuring; the Empire sustained Scottish industry at home too. All those ships and locomotives had to be built somewhere and they gave home-based Scots a stake in the Empire as well.

This is not as ‘ground-breaking’ a work as its publishers claim. Other historians including, but far from limited to, Sir Tom Devine and Michael Fry have ploughed some of the same fields. The Scot abroad is no longer, if it ever truly was, a niche or undercover subject. Nevertheless, there is much to admire here. If Pittock occasionally veers close to history-as-listicle – ‘The Top 50 Scots Who Built Canada’ – the sweep of his history and the panache with which it is written more than compensate for this.

Pittock’s sympathies are softly nationalist but not so very far removed from the traditional Unionist concept of the Union. There is, he suggests, a ‘strange tendency… to treat countries without states as potentially or actually illegitimate entities’. If he underplays the enduring strength of the Union – it is not just a matter of ‘nostalgia’ – it remains the case that the sense of a different, or possible, Scotland is a powerful driver of the current nationalist supremacy even if, paradoxically, its keenest supporters see it as a means of guaranteeing ‘a modernised version of the 1945-79 British social and welfare compact’. Hence this irony: to be authentically Scottish, Scotland must also be truly British. That is something for partisans on both sides of the national disputation to ponder.

The next PM must be ready for Putin

Westminster is understandably obsessed with the question of who makes the final two of the Tory leadership race, but today has also brought a reminder of the crises that the new Prime Minister will have to deal with from day one.

The European Commission is calling on all EU member states to cut gas use by 15 per cent to prepare for supply cuts from Russia through Nord Stream 1, which reopens tomorrow. With the pipeline only flowing at limited levels, and the heatwave leading to higher energy use than usual, Germany will not be able to lay in stores for the winter. This means that Vladimir Putin will constantly try and use energy as a weapon in the coming months, threatening to cut off supplies completely if the West does this or that in support of Ukraine. The price of energy will continue to shoot up in Europe, putting households under pressure and making various forms of economic activity unprofitable. I suspect there will be huge pressure this autumn on governments to bail out various industries.

The West must do what it can to handle the Russian energy threat. This means extending the life of nuclear power plants wherever possible, as well as pushing for as much more renewable energy use.

Will it be a Truss vs Sunak final?

The last stage of the parliamentary rounds of the leadership contest is here. This afternoon, MPs will vote to decide which two out of Penny Mordaunt, Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak progresses to the final round, in which they are whittled down to one by the party membership. The new leader will be announced at the beginning of September. Although Mordaunt came out in second place in yesterday’s ballot, there is a growing consensus among MPs that the most likely result today is a Truss vs Sunak final. The fact that Kemi Badenoch was knocked out in the fourth ballot means that the right of the party ought to be able to unite around the Foreign Secretary as their preferred candidate.

The numbers have been so tight so far that there is still room for an upset

However, the numbers have been so tight so far that there is still room for an upset – even frontrunner Sunak is yet to hit the 120 required to reach the final round. The various campaign teams have had a long night hitting the phones to try to win over as many of Badenoch’s 59 supporters as they can. As one such backer put it on GB News this morning: ‘My phone hasn’t stopped; I’ve never been so popular! But no one has offered me an ice cream yet.’

For now, Team Mordaunt is digging in. Her campaign stepped up a gear this morning as her personal account tweeted (and then deleted) a Telegraph article with the headline: ‘Tory MPs – vote for Rishi Sunak or Liz Truss today and you’ll murder the party you love’. A supporter of Truss tells Coffee House: ‘Things can only get better given the day began with us having to see off Penny’s death squads. If only such murderous intent had been applied to her day job.’

Once the final two are announced at 4 p.m., the candidates will quickly move to the second stage of their campaigns. While they technically have the whole summer to campaign, time is of the essence. Once members receive their ballots in early August, they could return them rather quickly. This means there is an incentive to hit the ground running – particularly for Sunak, as membership polling suggests he has work to do to win over the grassroots. The former chancellor’s supporters are encouraged by recent polling that suggests he has enjoyed a 13 per cent swing towards him with the members in less than a week.

If it is a Truss vs Sunak final, the Foreign Secretary starts out as the grassroots’ favourite. Expect Team Sunak to get him out in the country and featured in the media as much as possible in a bid to change that. This will begin in earnest on Monday when the final two face off in a televised BBC debate. The hope among MPs is that the candidates will refrain from the blue-on-blue attacks that have defined the debates so far.

Kemi Badenoch will be the new Tory leader’s secret weapon

There was an unmistakable whiff of an Addams Family portrait about the cabinet photocall that marked the final gathering of Boris Johnson’s top team. Surrounding the departing Prime Minister were many ministers who will have suspected that they are not going to be in the same ministerial positions, or perhaps any ministerial position, when 10 Downing Street is under new management.

To what extent, for example, can Nadhim Zahawi put together any kind of economic agenda, given his disastrous first fortnight as chancellor? His first few days in office saw him pledge an arbitrary tax-cutting timetable before his leadership hopes promptly collapsed amid reports that his own tax affairs were under investigation.

Those Johnson arch-loyalists Nadine Dorries and Jacob Rees-Mogg may reasonably suspect their continued shelf-life as major frontbenchers depends entirely on Liz Truss emerging triumphant from the leadership contest. Priti Patel is becalmed as Home Secretary given that her flagship Rwanda policy has been put on hold at least until the autumn.

This age of Conservative cowardice may be drawing to a close

Meanwhile those brought in simply to plug gaps left by recent mass-resignations, including Shailesh Vara and Greg Clark, are not so naïve as to think they have time to put down roots.

‘The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters,’ wrote the political theorist Antonio Gramsci, which may seem harsh when applied to this motley crew, but nicely captures the sense of interregnum.

The new world, we know, will be born in early September. And one politician bound to feature heavily in it will be Kemi Badenoch, the former equalities minister who so exceeded expectations during a leadership campaign that confidently fed core Conservative principles to a party grown weary of a dreary diet of accommodations with progressives.

Badenoch managed to articulate for the Tories the sense of what John Prescott once dubbed within Labour as ‘traditional values in a modern setting’. Without ever appearing out-of-date or so right-wing as to alienate majority opinion, she spoke up convincingly for smaller and leaner government, immigration control, bolstering the institution of the family, freedom of expression and respect for the nation state.

After seeing her cabinet claims studiously overlooked by Johnson during several reshuffles, she is all but guaranteed a plum post in the new regime after having forced herself centre-stage. As someone who understands her own worth, including as an analytical thinker, she is unlikely to sell herself cheaply either.

She could easily become the new Michael Gove – the next administration’s big strategic brain – should the old Michael Gove finally be allocated to a great office of state. Or she could be given a major portfolio herself, perhaps health or education with the equalities brief thrown in for good measure.

It will be fascinating to see whether the next prime minister has the confidence to allow Badenoch to shape the personality of the administration or ends up fearing her rock star popularity with the party membership and ability to communicate a distinctly Conservative sense of mission.

It is this last factor that has most endeared her to many long-serving grassroots members who still smart at the memory of being dubbed ‘the nasty party’ by Theresa May because of their core social conservatism. While May swallowed whole some flawed and faddish progressive approaches on issues such as gender self-ID or stop-and-search, Johnson often appeared entirely uninterested in political first principles, thinking his own giant personality sufficient to keep any show on the road.

While Badenoch has not yet publicly endorsed any of the remaining candidates, it is clear that she takes a contrary view to Penny Mordaunt about how to approach the tenets of the her left-wing opponents. Put simply, one wants to beat them, the other to join them. It is quite clear which approach will command majority support among Tories out in the country.

This ‘culture war’ agenda is far from all-encompassing for Badenoch, but she is never going to tap dance around it either. As one source close to her recently told me: ‘She didn’t become an MP to fight the identitarian left, she just had to do it because so many of the others are cowards.’

Mercifully, this age of Conservative cowardice may be drawing to a close. Kemi Badenoch’s gate-crashing of the inner-sanctum won’t change the formidable list of challenges facing the next PM, but it will mean that a sense of mission is likely to be restored.

The ruthless inefficiency of the Tory party

It is hard to love the Conservative party. But one reason it has at least always commanded a certain amount of respect is thanks to its reputation for ruthless efficiency. Personally I have found that reputation to be only half true. It is true that the party can be ruthless, but only in being ruthlessly inefficient.

Look at the mechanism by which it removed the Prime Minister who brought it its largest majority since Margaret Thatcher. True, Boris Johnson had his faults. But did the party not know these in advance? Why was it not able to add the stabilisers so obviously needed to keep a rickety, not to mention rackety, figure in the top job once it had placed him there?

It should cause no surprise. For this is of course the party that gave us John Major, William Hague and Iain Duncan Smith, elevating each in turn only to discover each time that a knifing was sadly necessary. It is the party whose most successful leader in recent decades was David Cameron, who entered parliament in 2001, was swiftly enthroned in the top job, managed to form a minority coalition government, and was out of parliament again within just 15 years. It is the party that then gave us Theresa May as prime minister, after a period in which there was a brief, Penny Mordaunt-like fever to make Andrea Leadsom run the country.

Now here we are again. The parliamentary party has done what it is so good at. The political assassination has occurred. The 1922 Committee has once again become a subject of national interest. And the Conservatives have once again presented the country with a lot of people who would be perfectly good ministers of state, but nobody who seems wildly obvious prime ministerial material. At least the assassins of Julius Caesar had a plan of sorts for afterwards.

Personally I have found most of the race to be excruciating. All the vices of the Conservative parliamentary members and grassroots are there on full view. The appeals to things like ‘one-nation conservatism’ which mean absolutely nothing to the wider public, even if any of the party faithful understand. Then there is the permanent temptation to put the whole future of the country in the hands of almost any plausibly matron-like figure. The perpetual desire of the Tory male to feel the personal smack of firm government.

At the time of writing, we only know who the last three are. But even among the three of them there is a cloud of doubt.

At least the assassins of Julius Caesar had a plan of sorts for afterwards

Mordaunt has been the subject of sustained attacks from her rivals. But all seem to be deserved. It is true that when she had the equalities portfolio (a job any real Conservative government would scrap) she oversaw – either deliberately or ignorantly – some deeply unsound policies on trans issues. It is also true that she went off-piste in meeting with a Muslim group which was deemed too radical to engage with not just by each recent Conservative government, but by the last Labour government. Ask Hazel Blears.

Liz Truss exudes an impression of competency, but it does seem like an impression. Like someone who has seen an effective person at work and knows how to pretend to be such a person. That said, I wasn’t much more taken with Rishi Sunak in the debates. In the second debate he tried to trap Truss by asking her which of her past mistakes – being a Liberal Democrat in the 1990s, or a Remainer in 2016 – she regretted more. For once Truss was passed the ball and kicked it quite expertly back into Rishi’s net, describing her journey to conservatism with some real conviction. It was an interesting reply, but much more interesting was the helpless look that came across Sunak’s face as he saw his trap go wrong. His eyes started to go down, he began avoiding eye contact and his smile of faux-sincere interest started to take on a rictus quality and then a sweaty one. It was the reaction of a political novice.

He is probably the person best suited for the top job. But moments of weakness like that do not fill me with confidence. A prime minister must know how to master any such situation. They should be hungry. They should be willing and able to bite the head off any opponent. Sunak looks too much like someone who has floated to the top and rarely had to get his hands dirty with political debate, never mind political warfare.

How did the Tories get into this state? Well one answer is that it is the state that the Conservative party is always in. The ghastly re-emergence of Major in recent days should be a reminder of that. But I cannot help thinking that it has also been held back by the horrible slowness of this country’s political discourse in recent years. Kemi Badenoch did terrifically in the debates and in her run for leader. She should get a good job in the next cabinet. But what does it say about the state of political discourse in Britain that the candidates had to get engaged in a debate about trans issues which just five years ago would have been regarded as disqualifying for a pass in GCSE biology?

It is the same with other issues that gunked up the debates. Where was the real discussion of economic vision? Of what the candidates would do to address inflation, the cost of living and more? While Mordaunt’s ignorance on trans and Muslim issues was brought to the fore, it also made the whole leadership race effectively have to go at the pace of the slowest kid in the class.

The Conservatives have treated themselves to another brutally inefficient leadership contest. Most of the public has no idea who these people are, and nothing much to get excited about. Whoever gets the prize has a couple of years to turn this country around. If they don’t, we won’t be talking about Red Walls, but a Red Wave coming.

Mordaunt: Truss or Sunak will ‘murder’ us

Throughout the leadership race, Penny Mordaunt has sought to portray herself as the cleanest candidate of them all. She has bemoaned the ‘toxic politics’ and ‘smears’ of others and bewailed how ‘this contest is in danger of slipping into something else’. She, by contrast, has pledged to run a ‘truly clean campaign’ and ‘committed to a clean start for our party’ – away from all from the attacks, lies and backstabbing of the past.

Mordaunt even told Steerpike’s colleague Isabel Hardman on The Spectator podcast just yesterday that:

I have conducted my campaign in a way that I think is needed and has been the right thing to do. Now more than ever. We’ve got to restore some positivity and some professionalism to what we do… I also think they they want to see the party being brought together in terms of the we’ve got so many caucuses and clearly it’s been a contest to date where fault lines have been stamped on and we need to set out a vision that will unite the party.

So it was somewhat surprise then that, just hours ahead of the final 1922 ballot, Penny Mordaunt’s personal account tweeted: ‘Tory MPs – vote for Rishi Sunak or Liz Truss today and you’ll murder the party you love.’ What happened to all that talk about unity, positivity and professionalism then eh?

Mordaunt’s defenders will suggest she was just quoting the headline of an article by Telegraph columnist Allison Pearson. But to use such inflammatory rhetoric just days after featuring praise for Jo Cox in a campaign video seems jarring, to say the least. Sunak and Truss served alongside Mordaunt together in government; they can hardly be said to be the King Herod and Salome of the Tory party.

It’s not the first time too that the Mordaunt camp has messed up on comms: on Sunday her official Instagram account shared a post which claimed ‘Rishi back stabbed the boss to get his job’ and ‘Liz is the bosses puppet. It was up for more than 15 hours before being belatedly removed.

Mordaunt, more than any of the three remaining candidates, has clearly been riled by various criticisms of her in the press. How exactly can she take the moral high ground now?

Soaring inflation could tank Rishi Sunak’s Tory leadership bid

Wages are rising. The economy is growing. The stock market is on the way up, and exports are booming. As he prepares for a long summer trying to persuade the membership of the Conservative party to make him prime minister, Rishi Sunak probably wishes he could be transported to some parallel universe where he could boast about his record as Chancellor. The trouble is, he is stuck with this one: and the news is relentlessly bad.

This morning, inflation was up yet again, hitting a 40-year-high of 9.4 per cent. Yesterday, it was real wages falling sharply, as workers’ income failed to keep up with rising prices. Over the next six weeks, as Sunak is out on the hustings hustling for votes, it is only going to get worse and worse. We are likely to see a fall in GDP (people taking a couple of days off because of the heat won’t have helped output); a record trade deficit, exceeding even last month’s terrible figures; a steep rise in interest rates making mortgages more costly; and a falling pound, making holidays more expensive. Put simply, it’s all doom and gloom.

Sunak will be running for the leadership with arguably the worst record of any Chancellor since Ted Heath’s finance minister Tony Barber in the early 1970s

It’s true that this is not necessarily Sunak’s fault. The entire global economy is in trouble. And the UK may well be in better shape than many of its rivals and will bounce back quite quickly. But it won’t happen over the summer.

In reality, Sunak will be running for the leadership with arguably the worst record of any Chancellor since Ted Heath’s finance minister Tony Barber in the early 1970s (and possibly even worse). It is hardly an enviable task. And it will undermine his claim to be the sensible, safe pair of hands.

Sunak could break free of this dire reputation. He could easily blame the tax rises and the wild spending on Boris Johnson, and he could blame the Bank of England for printing too much money. Sunak could also pledge to ditch at least one of the tax rises he imposed on the economy (the crazy rise in corporation tax would be the obvious one to start with) and set out some bold and detailed plans to control the size of the state and steadily bring taxes down. But so far he has refused to do so. Instead he seems stuck in a 2020 ‘dishy Rishi’ time warp where giving away vast sums of printed money was briefly mistaken for economic brilliance. In reality if Sunak chooses to run on his record at No. 11, he will certainly lose – and rightly so.

Penny attacks Truss over China

Dividing lines and clear blue water – in any election it’s crucial for candidates to find and exploits the distinctions between themselves and their rivals. Could China perhaps be one? It was the subject which Liz Truss chose to quiz Rishi Sunak about on Sunday and is seen by allies of the former as a weakness for the latter. The Foreign Secretary is keen to appear more hawkish than her rival; under Sunak’s Chancellorship the Treasury tried to restart multiple high-level financial dialogues with Beijing.

And it’s not just Truss pushing this line, for Penny Mordaunt has now decided to jump on board the China train. She declared last night that ‘We have been too soft on China. I won’t be’ after her campaign team briefed the Express about her plans for a new ‘China Strategy’ and a harder line on Beijing. It’s a not-so veiled swipe at Truss’s tenure at the Foreign Office and a savvy political move. China bashing is a good vote winner among both Tory MPs and Tory members; Beijing to Britain notes that the UK electorate view sthe rise of China as one of the country’s three most prominent security threats.

The problem is that, er, the UK already has a ‘China Strategy’ and one on the Indo-Pacific region too. The Express reports that Mordaunt ‘will pledge to conduct a full review of UK-China policy, across all Government departments’ yet this has been (slowly) ongoing for months now in Whitehall. Longtime China campaigner Luke de Pulford claimed that Mordaunt hasn’t shown much interest in the area before, saying ‘she hasn’t spoken in a single debate on Uyghurs, Taiwan, Hong Kong or Tibet – even when not a minister.’

Her pledge to hold Beijing to account for its actions in Xinjiang also should be seen in the context of her time at Trade, where she claimed that if ‘you want to “defend against authoritarianism, fight corruption and promote respect for human rights” then place trade at the centre of all you do.’ Mordaunt’s plan does contain some interesting ideas: sanctions for those implicated in the Hong Kong crackdown and the Xinjiang abuses plus greater monitoring of China’s investment in infrastructure.

But coming just hours before the 1:00 p.m ballot for the Tory leadership race, it might all be too late to save her from being eliminated from the final two. The question is, will Truss and Sunak also campaign on this theme? Or will China be overshadowed, once again, by other competing domestic concerns.

Wanted: senior digital marketing executive

How would you describe The Spectator? And how would you sell it to someone who had never read us before? Some of the most important words we write never appear in the magazine: they’re from our ten-strong marketing department. They’re now looking for a senior digital marketing exec: it’s a mid-level job to learn from and get stuck into the world’s greatest publication and join the team here in 22 Old Queen Street.

You will be …

- Looking at the emails we send to readers who don’t (yet) subscribe. How to best persuade them to sign up? Which emails work the best? Which ones to send out and when? Technology gives us a pretty good idea, and you’ll be using it to keep score.

- How to make the case for The Spectator in social media. And how to make sure our various messages are consistent, as we intend them to be.

- Dealing with the agencies we use, to make sure they stay on message.

- What do new users see when they come on the website first of all? Is it inviting – or jarring? Small changes can make huge differences in this, the ‘meter journey’ and you’ll be involved in honing it.

- Keeping an eye on our app. How many are using it? What tips can we find in the data for how to improve?

Your raw material is the world’s oldest (and best) magazine. If you can look at our current adverts and say what’s wrong with them — or how to improve them — and master the art of digital marketing then we’d love to hear from you. Apply here.

Kemi Badenoch’s role in the Tory leadership race isn’t over yet

Kemi Badenoch, the Tory leadership contest’s Emma Raducanu, finally lost momentum. She put on just one vote to secure 59 backers, and is out. But that’s not the end of her story in this battle to find Britain’s next prime minister. Where she and her supporters now place their votes will determine which two Tory MPs are whittled to one by the votes of 160,000 ordinary members of the Conservative party.

It would be extraordinary if Badenoch threw her weight behind Penny Mordaunt, given her highly personal charge that Mordaunt as equalities minister was too liberal in her policy towards trans people. It’s a charge that Mordaunt has rejected, but there’s no hint of forgive and forget on either side.

What about Badenoch’s highest profile supporter, Michael Gove? I doubt he’ll reveal who he is backing next. But right from the start it has been widely assumed in Westminster he’ll end up as a Sunak supporter.

What about Badenoch’s highest profile supporter, Michael Gove?

Sunak is not home and dry. He’s still two votes short of a clear victory. And if he wants to have a following wind as the contest moves to the membership-hustings phases, he needs to win today by a comprehensive margin.

So Sunak will be hoping and praying that somehow Gove can shift most of Badenoch’s 59 supporters his way. MPs are resistant to being whipped in these contests. Some of Badenoch’s will prefer Mordaunt or Truss.

And as I understand it, the two MPs in charge of the organisational side of Sunak’s campaign – the former whips Mark Harper and Mel Stride – won’t lend any of their votes to any of the other candidates. According to one Sunak supporter, the ex-chancellor is now focused on winning this part of the contest as comprehensively as possible.

‘Rishi has no preferred candidate for the members’ phase,’ said the source. ‘If he’s lucky enough to get there, he’d be delighted to face any one’.

For what it’s worth, betting markets now believe that third-placed Truss – with 86 votes to Mordaunt’s 92 – is not only most likely to get through to the final run-off but will end up as PM.

I understand punters’ logic. They can’t see how Badenoch fans could possibly back Mordaunt, given the apparent antipathy between Badenoch and Mordaunt. And several MPs have told me this analysis is correct.

But I would just caution that in a secret ballot, with hours to go for the remaining candidates to persuade and bully and bribe their MPs colleagues, none of the three is a racing certainty.

The Online Safety Bill won’t survive the Tory contest

At yesterday’s Spectator hustings for the final three Tory leadership candidates, each one of them ended up committing to overhauling the controversial Online Safety Bill. The Spectator and many Conservative MPs have expressed serious concerns about the impact of this legislation, drawn up with the best of intentions, on free speech.

Each acknowledged that there was a real problem with the current drafting, which creates a new definition of ‘legal but harmful’. Kemi Badenoch, who was knocked out yesterday, had described this as cracking down on free speech to prevent ‘hurt feelings’, which is something none of them fully accepted. But they all saw that ‘legal but harmful’ as it currently stands is a bit of a one man’s meat is another man’s poison situation.

It’s worth noting that both Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak said their approach to the legislation was based on their own experiences as parents and their fears about their daughters accessing damaging things online. It is why Culture Secretary Nadine Dorries and her opposite number Lucy Powell are both confident about defending the Bill: they know that parents are desperate for something to be done about the Wild West of the online world for children.

The problem is that when politicians create Something Must Be Done bills, they often end up with legislation that creates a lot of new problems that weren’t properly addressed because everyone was so focused on the principle, not the detail.

You can read below what each candidate said in full on this matter, or watch it here.

Kemi Badenoch, who was knocked out yesterday, had described this as cracking down on free speech to prevent ‘hurt feelings’

Rishi Sunak:

‘I come at this first as a parent. I have two young girls who are at the age where they’re starting to go online more. And I’ve got to tell you, I’m quite worried about all of that. And I sit down with my wife and we talk about it. I’m concerned about what they could end up looking at. And I think the exposure to explicit, sometimes horrific material at such a young age is wrong. And we’ve got to find a way to protect children against that in the same way as we do in the offline world, so to speak. So that’s my first start. So I think we do need to have something that does that. But with the bill, I think the challenge we’ve got, and that’s why I’m glad the government’s paused the bill so we can refine our approach here, that the challenge is whether it strays into the territory of suppressing free speech. And the bit in particular that has caused some concern and questions is around this area where the government is saying, look, here’s some content that’s legal but harmful, and it’s that that’s this kind of area, which I think people rightly have said, well, what exactly does that mean? And that’s the bit that I would want as prime minister to go and look at to make sure that we get that right.’

IH: So you’re pledging to potentially scrap the legal but harmful section.

RS: ‘Again, I know you’re trying to push me into the direction of getting a firm pledge. What I’m saying is I do think we need to have a way to protect children against harm, as I said and I say that first and foremost as a parent. But I do want to make sure that we are also protecting free speech and the legal but harmful bit is the one that I would want to spend some time as prime minister going over and making sure that we’re getting that bit exactly right. And I can’t tell you what the right answer at the end of that process will be. But I think it’s fair that people have raised some concerns about that and its impact on free speech. And I think it’s right that those concerns are properly addressed.’

Penny Mordaunt:

‘I do support the Bill. I would want to make progress on it, but I do understand the concerns that there are around how you define particular things in law and the chilling effect that it might have on freedom of speech. I think our government’s got a good track record on freedom of speech. I think that there’s always more we can do, but we have taken a real stand in a real grip on some of the issues affecting particularly on campuses and and elsewhere. I’m confident that we will be able to put a bill through that provides those reassurances. But clearly there are some pretty horrible things that need to be gripped, and that’s what the Bill does.’

IH: So the issue of concern for The Spectator is that it would outlaw free speech by creating a new category of legal but harmful. What does legal but harmful mean to you?

‘So it is difficult to define. This is the weak point because it is difficult to define these things in law because what you know, what might offend one person might be perfectly all right for another. And I think unless you can really define that in law, there’s a problem. But we do have existing laws where people are causing real material harm to people, when people are stalked, for example, that I think we could draw on. But I do recognise the need that any law we’re putting through has to have clarity. And if we can’t provide that clarity, it’s not going to work. So I’m prepared to look at those issues.’

IH: Someone being followed and monitored online is very different to somebody being distressed, as the bill itself puts it in one of its clauses by something that somebody else is saying online. I mean, we all have our different trigger points, so how would you protect that? That’s one of the issues that one of your rivals, Kemi Badenoch, has referred to the hurt feelings clause, I think she’s put it.

‘Yes. But I don’t think this is about hurt feelings. I think this is about elements of stalking or causing really severe distress to people. But again, this bill is very targeted at other issues. I think we also need to look at the business model of some of the platforms that we’re talking about, platforms that one suspects don’t have real people on them, and how some of those accounts and bots are being weaponised to to cause distress or spread misinformation. But I, I think the bottom line is, unless you can define this categorically in law, it’s not going to be a good law and therefore best not make it.’

Liz Truss:

‘I’m a believer in freedom of speech. I also believe that we need to protect particularly the under 18s from harm. And what I want to make sure with the Bill, and I know it’s now going to the House of Lords, is that it strikes the balance correctly between those two things.’

IH: Do you think it does at the moment?

‘Well, I need to look into more detail about exactly how it is implemented and have discussions with my colleagues. But the principles I believe in are the protection of free speech, but also making sure that we’re not exposing under 18s to harm online. And, you know, I’ve got two teenage daughters. I am very, very concerned about the effect particularly social media has on teenage girls or mental health. So I will want to look at that and make sure that that is in the right place, as well as protecting freedom of speech, freedom of the press. I’m a great believer that those are core freedoms that a healthy society depends on.’

IH: There’s a big difference, though, isn’t there, between social media outlets that promote eating disorders, that display sexually explicit content and so on? And one of the things that The Spectator is particularly worried about in the Bill, which is this new category of legal but harmful, which we think is going to basically outlaw legal free speech. Do you know what legal but harmful means?

‘There’s more nuance in the Bill than that. But I’d be very keen to talk to The Spectator and others to make sure the Bill delivers what we want it to deliver. And this is a complicated area. I speak to colleagues around the world who are looking at how to legislate for online spaces, you know the fundamental principle is the rules should be the same online as they are in real life. I think that’s a fundamental principle and that’s what I will make sure I apply.’

IH: You don’t agree with the hurt feelings characterisation that some of your fellow candidates have used to describe this Bill?

‘Well, as I’ve said, I’ll need to look at exactly, you know, these issues are necessarily complex and nuanced. And I think there is a place for further amendments to this legislation to make sure we’re delivering it and also make sure that everybody is aware of the intention of the Bill as well, which is also important. So I’m committed to doing that, but I think I’ve set out very clearly the principles I believe in.’

The Union is in trouble whoever wins the Tory leadership race

It’s not a question that has enjoyed much play in the Tory leadership election but it’s a pretty important one: Should the United Kingdom continue to exist? That is essentially what Isabel Hardman tried to tease out of the three remaining candidates in The Spectator hustings, which comprised separate head-to-head interviews. Penny Mordaunt and Liz Truss were interviewed in person at The Spectator offices while Rishi Sunak spoke to Isabel down the line.

None of the candidates had any great insight into how to preserve the UK. None broached fundamental questions, such as the inherent flaws of a devolved settlement that allows the Scottish government to use taxpayers’ money to constantly campaign for the dismantling of the UK. However, the exchanges were useful in recording how each instinctively reacted to a question about allowing another referendum. Each candidate was asked:

None of the candidates had any great insight into how to preserve the UK

‘Are there any circumstances in which you would agree to a second Scottish independence referendum?’

It was obvious that one candidate in particular struggled to speak extemporaneously about this matter. Decide for yourself who you think that is from this transcript.

Penny Mordaunt:

PM: ‘I think this is a – a settled question. Uh, we recently had, uh, a referendum and this is not, uh, going to be something that I’m going to be looking at. We, we have so many more priorities and I think the people of Scotland, uh, want us to focus on the things that are of genuine concern to them. Cost of living. Uh, ensuring that the Scottish government is actually delivering for them on healthcare and other issues. So, uh, no, I – I – I’m – I’m not looking at that.’

Rishi Sunak:

RS: ‘This is… this process is now… playing out in the courts and the Supreme Court will make a decision… you know, I – I – you know, my… [laughs] I think I – I – I hope that they will, they will decide that, you know, it’s rightly for the constitution sets out how that’s meant to work, so, you know, that court process will play out. My – my general… view on the matter is: I – I care very deeply about the Union and I think, of all the challenges we’ve got ahead of us now, I think most people… in Scotland especially would agree that that’s not the priority right now is to have a – a divisive referendum. The priority for… all governments that represent them, and administrations that represent them, is to tackle the economic challenges that they’re facing with the cost of living and that’s what I certainly will be focused on doing and it – you know, I don’t think arguing about another referendum now is – is remotely the right priority.’

Liz Truss:

LT: ‘No.’

Isabel Hardman: ‘None at all?’

LT: ‘Well… the last referendum in 2014 was described as a ‘once in a generation’ referendum and we’re now in 2022. That is not a generation ago.’

The secret holiday spots beloved by the Spanish

Ask a Spaniard where they vacation, and you may get a touch of the Matador effect in response. The chest lifts, the head is tilted up with the bottom lip pushed out accompanied by the reply: ‘España! My country.’ For like the Greeks, when you have so many domestic splendours to choose from, why would you go anywhere else?

It’s estimated that about two out of three vacationing Spaniards remain in country for the holidays. But where do the Spanish go? It’s a bit of a mystery—perhaps intentionally so. With swarms of Brits inundating their land, you can’t blame the Spanish for wanting to safeguard a few vacation refuges.

Recently I’ve been encountering Spaniards on the move for their holidays. In the picturesque village of Requejo toward the north of Spain, I passed a car parked with its bonnet popped open, all doors ajar and its three passengers sitting on the pavement sipping drinks to cool down. Mid-afternoon, the temperature was peaking at around 35 degrees. They told me there were heading to the city of Pontevedra amid the cooler climes of Galicia, Spain’s most north-western region. Located on the edge of an estuary at the mouth of the Lérez river by the sea, Pontevedra contains a charming old town full of exquisite architecture (though arguably that isn’t much of a boast in Spain: most cities match that).

Galicia remains a Spanish secret, unless you have done the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage that ends in its regional capital, Santiago de Compostela. But the region is an enigmatic treat, with a starkly unique and independent character from the rest of Spain. Its lush verdant landscape is often compared to Ireland’s. You often encounter Celtic crosses at the intersections of rural tracks. You might even hear the bagpipes being played. In addition to kinder summer temperatures, Galicia’s coastline bequeaths a regional cuisine strongly based on fish and seafood. The region is famed for its fried pulpo—octopus—and Albariño, a white wine with strong floral and citrous undertones.

As I discovered during an extended Camino during the pandemic, from Galicia eastward stretches a rugged and beguiling coastline known as ‘Green Spain’, where forests and rocky hillsides meet glittering beaches. While largely unknown to foreigners who tend to pour southward, Spain’s northern coastal regions of Asturias and Cantabria are especially popular with Spaniards going camping or looking for surf. Asturias is also known for its fine cider— sidra —and for its bar staff who pour the cider from a bottle held above one’s head into a glass held around one’s knees (this helps oxidise the cider and release its flavours) while consciously looking in the wrong direction.

The coastline of the southern region of Andalusia is also a big draw for Spaniards come summertime. Even the exquisite delights of Seville, the Andalusian regional capital, are not enough to ameliorate the infernal summer heat. Come August, there’s a mass exodus of locals, leaving Seville’s British expat community—especially its impoverished teachers of English as a second language—sweating it out. They at least make the most of being able to get into fancier restaurants more easily and cheaply.

You may be noticing a theme here. Once the interior of Spain and its cities gets unbearably hot, everyone heads outward to the beach. And if that means having to share a beach and bar with Brits and their sangrias, then so be it. Anything but that torpid heat sitting on top of you! Hence coastal areas favoured by Brits, such as the Costa Brava in north-eastern Spain’s Catalonia region and Valencia further down in the middle of Spain’s eastern coastline abutting the Mediterranean Sea, are popular destinations for Spaniards.

At the same time, most Spanish cities have their local getaways that remain under the radar of tourists. A good example is Sitges, an idyllic beach town 25 miles south down the road from Barcelona. Its ornate architecture came from young Spanish men who in the 19th century went to Cuba to seek their fortunes and returned successful. Cadiz on the western coastline of Andalusia, despite having declined since its heyday—as described in a recent Spectator review — retains a laid-back atmosphere amid the ‘cool gloaming in these deep, narrow, crevasse-like streets’ that continues to attract Spanish locals, especially those from Seville who can get there easily by car or train.

By way of a handy backup, the Balearic Islands of Ibiza, Mallorca, Formentera and Menorca and then the otherworldly beauty of the Canary Islands are part of Spain. While they take more effort to get to, arguably they offer the best of both worlds for Spaniards: getting away from it all while remaining in a familiar orbit of reliable tapas, affordable good wine and the Spanish lingo and customs.

The Spanish are not entirely immune to the allure of foreign climes. For those venturing aboard, Italy is the most popular destination, followed by France and then Spain’s neighbour Portugal. About five per cent of holidaying Spaniards brave the UK, with London the main draw. But the most popular holiday strategy for the Spanish seems to be not to roam too far from home, and who can blame them?

The Conservative party has ceased to be serious

I’m not sure that the Conservative party wants to win elections. Tom Tugendhat was knocked out of the leadership contest on Monday, and Liz Truss is now the bookies’ favourite to be the next Prime Minister. Any party that thinks the latter beats the former cannot say it is serious.

There are several reasons for Conservatives to ignore me on this topic. First, I’m not a Conservative. Second, Tugendhat and I are friends. Third, I take a view of party politics that seems to be utterly out of fashion these days.

That view is that politics works better when parties try to win the other side’s votes. When Conservatives pursue Labour voters, the worst bits of right-wing conservatism are muted. When Labour woos Tory supporters, the worst bits of the left are sidelined. In practical terms, this means I want Tories to be more compassionate towards the less fortunate, to care more about inequality, and be less starry-eyed about free markets. I want Labour to be more sympathetic towards business, to care more about taxpayers’ money, and be less starry-eyed about state provision of services.

But the Conservative party isn’t thinking practically: it’s talking to itself. The days of Tony Blair – whose priority was to make the other side as uncomfortable as possible – seem a long time ago. David Cameron once told me how much he hated the experience of facing Blair: ‘Every morning, I wake up thinking, “what’s that bloody man going to do to take away my voters today?”’

You can’t go far wrong if you always try to do the thing that your opponent least wants you to do

If the Conservatives had wanted to have a leader with that skill – the strongest popular appeal to the whole electorate – more of them would have voted for Tom Tugendhat.

One Tory friend contacted me over the weekend to explain why they hadn’t: ‘he’s more popular with Labour voters than [with] Tories’, they said. Apparently, the whole aim of Tory political strategy these days is to hold on to as much of the 2019 vote as possible, to preserve that 80-seat majority. Keeping Conservative voters is their task, not winning over Labour ones.

This strategy misses something rather important. Quite a lot of 2019 Tory voters don’t intend to vote Tory again. A lot have gone to the ‘don’t know’ polling category, and a fair few have moved to Labour. On Opinium’s latest voting intention poll, more than one in ten of the people who currently back Labour voted Conservative in 2019.

That means my Tory friend has it wrong. Retaining Boris Johnson’s 2019 coalition doesn’t mean consolidating Conservative votes, it means winning back Labour supporters. It means building a Conservative brand that appeals to the wavering.

Yet there has been almost no conversation about this goal in the leadership race so far. Of course, when the immediate electorate is Tory MPs and Tory members, it makes sense to focus on their priorities. But don’t those priorities include retaining power?

Winning will depend on the party’s ability to court non-Tory voters, yet the Conservatives have rejected the leadership candidate best-placed to win them over. Recent Opinium polling shows that Tugendhat had the greatest appeal to the general public, in part because of his ability to reach people who are currently recorded as non-Tories. His polling ‘win’ after Friday’s debate came because his performance was rated across the political spectrum.

When people who didn’t vote Tory last time were polled after Sunday night’s dismal debate, Tugendhat was rated as the candidate most likely to make them vote Conservative on 18 per cent. Truss was last on 4 per cent. Yet she is seen as a better bet for the leadership because current Tory voters like her. Tugendhat’s appeal to the wider public has counted against him, while Truss is now the bookies’ favourite to enter No. 10.

This is curious, to say the least. In 2019, the Conservative party elected Boris Johnson because he was a ‘Heineken Tory’, able to reach parts of the electorate that other candidates could not. What happened in the last three years? The party has rejected the one candidate who showed signs of having the Heineken appeal, albeit with somewhat different politics to Johnson, and is seriously considering a candidate who doesn’t appeal to non-Tories.

In politics as in sport, you can’t go far wrong if you always try to do the thing that your opponent least wants you to do. That’s why Cameron hated facing Blair so much, but found Gordon Brown a less troubling prospect. It’s why Blair loved Iain Duncan Smith and why the Tories were delighted by Jeremy Corbyn. Some of Truss’s biggest fans will be in Labour HQ.

The Conservatives had a chance to do something that would have made Keir Starmer uncomfortable. Instead, they are satisfying themselves. History suggests that a party that thinks about its own pleasure instead of hurting the other side isn’t really serious about winning.

Kemi Badenoch eliminated

Kemi Badenoch has been eliminated from the Tory leadership contest. Rishi Sunak came first with 118 Tory MPs backing him; Penny Mordaunt was second on 92; Liz Truss came third on 86. Badenoch was supported by 59 MPs. Refresh this page to read the latest:

5.15 p.m. Where will Kemi’s supporters go now?

Now that Kemi Badenoch has been eliminated from the Tory leadership race, the big question is who will her supporters back? Leo Docherty’s endorsement of Liz Truss suggests that at least some of Kemi’s supporters will opt for Truss over the other leadership contenders:

4.20 p.m. Kemi says thanks

4.20 p.m. Kemi out. What now?

With Kemi Badenoch eliminated, who will make the final cut? Katy Balls and James Forsyth give their verdict on a special edition of Spectator TV:

4.00 p.m. What the bookies think

Rishi Sunak remains the bookies’ favourite to become prime minister, but Liz Truss is not far behind:

3.35 p.m. Sunak’s ‘divide and conquer’ strategy

Steerpike writes… It’s been a pretty good few days for Team Sunak. Their man gave an assured performance in both debates and has enjoyed a brief respite from the more vituperative elements in the press. His closest rivals Penny Mordaunt and Liz Truss have instead come in for heavy criticism; Mordaunt for her (supposedly) woke views and lacklustre work ethic; Truss for her lack of polish. So why then has Sunak only picked up three ballots today?

Tom Tugendhat’s defeat meant that more than 30 votes were up for grabs. Two MPs – Mark Pawsey and Rehman Chishti – already went public to announce they would back Sunak. Can Sunak really have only gained one more vote in the past 18 hours?

Naturally this has led some in Westminster to mutter darkly about ‘vote lending’. They point to Penny Mordaunt, up by 10, despite a faltering few days. Much like Snowball in Animal Farm, the dark hand of Sir Gavin Williamson is suspected at every turn, pulling the strings for a Sunak victory much like he did for Theresa May and Boris Johnson before. Others counter that such talk is merely to destabilise other candidates. One thing is for sure: with Badenoch’s elimination, Sunak is the candidate who has run the most consistent campaign of all those who remain.

3.25 p.m. What Kemi’s defeat means for the Tories

Kate Andrews writes… Today’s ballot doesn’t just remove Kemi Badenoch from the race – it removes a host of policy areas, too. Badenoch fast became the favourite amongst the Tory grassroots, no doubt in part because of her willingness to be more direct about key policy topics. She is the only contender so far to come out against the Online Safety Bill, which threatens to crack down on free and legal forms of speech online. She also was most blunt about the UK’s net-zero targets; committing to the end-goal of zero-carbon emissions, but insisting she’d refuse to ‘bankrupt’ the UK to get there.

Badenoch’s tax approach was closer to Rishi Sunak’s. Both insisted ‘trade-offs’ must be made. Both highlighted the dangers of borrowing lots more money to bring forward tax cuts. If Tory grassroots agree with this economic philosophy, they’re all but certain to have a candidate to pick from over the next few weeks, with Sunak now just two votes away from clinching a place in the final two. And we’re now guaranteed a proper debate on tax-and-spend policy, with Penny Mordaunt (second place) and Liz Truss (third place) ready to make the case for more borrowing for day-to-day costs. But without Badenoch, there won’t be as much pressure to lay out an agenda in other major policy areas, not least because it will suit the others to commit to as little as possible on the path to No. 10.

3.20 p.m. Who will Gove back?

Isabel Hardman writes… Now one of the big questions is who will Michael Gove back? He gave a significant boost to Kemi Badenoch’s campaign by rowing in behind the self-styled ‘wildcard’ candidate. Now the party is really thinking about who is ready to be prime minister and, as Katy Balls says below, who can unite the right of the party. Gove is going to take some time to think about who to support now, though of course ‘some time’ means about half an hour given how frenzied the final 48 hours of this contest are going to be.

3.16 p.m. Is Rishi running out of steam?

Isabel Hardman writes… Rishi Sunak is still not guaranteed to be in the final two, having picked up just three votes to reach 118 today – two short of the 120 that gets him in. Is his campaign running out of steam, having been well-prepared in the run-up to Boris Johnson departing? It’s also worth noting, as I mentioned earlier, that there is a concerted revenge operation underway from team Boris to paint Sunak as duplicitous to wavering MPs. It may also be that the many MPs who’ve ended up thinking they could be Sunak’s chancellor are starting to wonder if they’ve picked up the wrong signals, given so many of their colleagues have the same impression.

3.15 p.m. A good result for Truss

James Forsyth writes… Kemi Badenoch is out after a very strong campaign. She has run a remarkably impressive campaign and to make the final four from outside the cabinet is quite a feat. She’ll now be courted heavily by the remaining leadership candidates.

Liz Truss will be pleased with the result, she has closed the gap on Penny Mordaunt to six votes and will hope that she can pick up more Badenoch votes than Mordaunt. The Mordaunt camp will have been disappointed to have only picked up 10 votes considering how it felt that there was an ideological overlap between them and the Tugendhat camp.

3.10 p.m. Who spoiled their ballot?

Isabel Hardman writes… Graham Brady told the committee room that there was one spoiled ballot paper in this contest and one not cast. Knowing the Tory party, even though this is a secret ballot, it’s unlikely we will have to wait that long until whoever wanted to make a point about the quality of candidates in the contest breaks cover to do so more widely. What’s more interesting – and will always be unknown – is that a secret ballot allows MPs to vote for someone other than the candidates they’ve publicly declared for. This is the most duplicitous electorate in the world, after all.

3.05 p.m. Will Kemi’s voters flock to Truss?

Katy Balls writes… Kemi Badenoch is out and the race is now on between the three remaining candidates for the final two. While Penny Mordaunt has retained second place, the results look good for Liz Truss. She is in third place on 86 votes – but there are now 59 votes up for grabs from Kemi Badenoch’s camp. Some of those – from the right of the party – are likely to go to the foreign secretary. The right finally has a candidate to unite around.

3 p.m. Kemi Badenoch eliminated

The results of the fourth round of the Tory leadership are in:

Rishi Sunak – 118 (+3)

Penny Mordaunt – 92 (+10)

Liz Truss – 86 (+15)

Eliminated: Kemi Badenoch – 59 (+1)

2.40 p.m. When the Tory war is over

Isabel Hardman writes… Yesterday Penny Mordaunt lost one vote from her second round result: today she’s down at least one more after Tobias Ellwood was stripped of the Tory whip for missing the confidence vote in the government. That Boris Johnson acted so fast on a vote that no-one thought he was going to lose is an interesting insight into the state of mind of the outgoing Prime Minister and those around him.

There is also significant bitterness in Team Boris towards Rishi Sunak, who is considered the key reason why Johnson ended up with no choice but to resign. The tension between groups of Johnson loyalists and anyone campaigning for Sunak is palpable in Parliament. At the moment it is very much a case of it being too risky for the two camps to merge in social settings like on the terrace. But once this contest is over, whoever is leader is going to have to work out a way of healing these angry wounds – or they’ll end up festering and causing damage to the new PM too.

2.35 p.m. Could tactical voting backfire?

Katy Balls writes… There’s much talk among MPs today of tactical voting. The idea being that MPs determined to stop Liz Truss progressing to the next round could lend their vote to another candidate in order to make that a reality. However, some of Tom Tugendhat’s backers with this aim are discussing temporarily backing Penny Mordaunt even though they really support Rishi Sunak as their preferred choice. This slightly misses the point. If MPs wanted to thwart Truss in this round, lending votes to Kemi Badenoch (who finished 4th in the third ballot) would be the way to do it. The problem with tactical voting is that it risks being too clever by half.

2.30 p.m. Who’s backing whom?

Conservative leadership ballots remain secret, but many Tory MPs have publicly declared which candidate they are backing. Sunak has the highest number of declared MPs in support with 75, then Penny Mordaunt on 45. Liz Truss comes third with 41 backers followed by Kemi Badenoch on 28. Read the full list here.

2.20 p.m. The results so far

When Tory MPs cast their ballots last night, Rishi Sunak, Kemi Badenoch and Liz Truss all enjoyed a surge in support. Tom Tugendhat, who had the lowest number of MPs backing him, was eliminated from the contest. Will Rishi continue to find the momentum going his way?

2.00 p.m. All to play for

James Forsyth writes… Today is the most unpredictable day of this contest so far. There are all sorts of cross-currents swirling around Westminster: some Tugendhat supporters’ primary objective is to block Truss now their candidate is out of the contest. But there are also those who aren’t fans of Penny Mordaunt – like Anne-Marie Trevelyan, who ran on Tugendhat’s ticket as his deputy, who yesterday said Mordaunt ‘left other ministers to pick up the pieces’ to plan her leadership bid. How this all balances out is hard to judge.

The joy of food on sticks