-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

The dark art of ‘off-rolling’ unwanted pupils

Sometimes a school wants to exclude a child but can’t. The student might have difficult needs that are costing money or taking too much time to deal with. Or their exam results might be looking likely to damage the school’s standing. But children can’t lawfully be excluded for getting bad grades or for needing more attention. Schools, though, have a way to get them off their books. They ‘off-roll’ them, a practice which is illegal.

In 2017, in the first widely reported case of off-rolling, St Olave’s grammar school in London told 16 pupils that their places in Year 13 had been withdrawn because they did badly in their AS-level exams, even though they had reached the sixth form entry requirements the year before. One father said his son was dumped like ‘old garbage’.

It seemed then like an isolated instance of a school trying to game the league tables. But a year later, a Times investigation found that 13,000 pupils had suspiciously vanished from government records just before their exams. They did not have any recorded results from their Year 11 GCSEs, despite being registered at a school in Year 10. Were schools systematically booting out poorly performing children to engineer their rankings?

In response to stories like these, Ofsted decided to prioritise inspecting schools with high levels of dropouts. The government also promised to review exclusion guidance and open a consultation to investigate off-rolling. It was originally meant to begin in summer 2020 but was delayed, inevitably, by Covid. The consultation finally opened last month.

Schools know they cannot exclude children for poor results. They just hope that parents don’t call their bluff

It has a lot to contend with because schools are off-rolling some students in increasingly creative ways. Parents, for example, might be told that their child is about to be excluded because of poor behaviour, and ‘advised’ (as schools like to put it) that they remove them themselves. Their child won’t have the black mark of exclusion against their record, the parents are told, so it’ll be easier for them to find another school. Schools know that they cannot exclude children for poor results. They just hope that parents don’t call their bluff.

Schools might also promise to have a place lined up for the child at a nearby college. The switch will be simple, they’ll say. In some cases, schools will block-buy places at colleges for this purpose. Spots cost a few thousand pounds. A school will make the money back in the time they save having the pupil off their hands.

One former secondary school teacher told me their school manipulated students’ records to keep them off their roll. Officials changed the status of poorly performing pupils to ‘guest’ — usually reserved for children who are between schools, perhaps because their parents have separated — meaning their exam results were kept off the books. In a year group of 120, around 15 students were off-rolled in this way, the teacher said, adding the children were left in ‘blissful ignorance’.

Academies have their own methods of off-rolling. They may for instance have their own alternative provision facility for troublesome children. In 2019, Tes, formerly the Times Education Supplement, published a leaked document from Farnley Academy exposing how they did it. ‘With Stephen Longfellow Academy starting in 2017, we have an opportunity to move students to an appropriate provision before they become an issue in KS4,’ the document read. The results of the school could be improved by the ‘removal of anchor students’ who had ‘not been able to achieve consistently’.

In 2013, Farnley, which is one of five schools in the GORSE Academies Trust, was given Ofsted’s highest ranking, ‘Outstanding’. In 2019, after inspectors confirmed they were off-rolling pupils, it was downgraded to ‘Requires improvement’.

Private schools are guilty, too. One independent secondary in Hertfordshire has informed several students’ parents that unless their child achieves 8s and 9s in their GCSEs, they won’t be coming back to the sixth form, even though the official entry requirements could be met with 5s and 6s. There have been ‘long and protracted conversations with parents’, a figure close to some of the pupils said. If the children don’t make the grades, they expect the school to produce a reason to exclude them. Most of these children have special needs.

Technical colleges, one education lawyer told me, are the ‘Wild West’ of off-rolling. While it’s illegal for schools to exclude students for bad attendance, colleges play ‘fast and loose’ with ditching students who don’t show up. There are laws on how and why schools can exclude pupils, but there are no similar rules for colleges.

Off-rolling even happens at primaries. While it’s usually related to a child’s particular needs that are difficult to deal with — exam results are less of a pressure — the lawyer said he knew of a handful of cases where schools wanted to game Year 6 SATs results by getting rid of badly performing ten- and 11-year-olds. Sometimes, he said, schools have fabricated excuses to remove children who come from traveller communities, which they deemed to be disruptive.

Teachers know that off-rolling happens. A YouGov poll found that more than three-quarters of teachers in England are aware of the practice, and nearly a quarter have witnessed it. The former teacher I spoke to told me there were ‘hushed conversations’ between school officials about the manipulation of students’ records. It is usually justified by citing schools’ financial pressures and the demands for better results put on them by the government.

Some have even argued that off-rolling benefits children. Students who struggle can learn better in a different environment, and pupils who need a more difficult curriculum can be challenged. In 2019, when Merseyside’s Sutton Academy was criticised by Ofsted for off-rolling students, the school argued that the practice was arranged by the local council, St Helens. It was done for the ‘benefit of all students’, the council said in a statement. Alison Sherman, the then principal, said some children had been moved to alternative education from as early as Year 8, just one year after joining the school.

In their eyes, off-rolling may have seemed akin to splitting children into sets, common at most schools for maths and sciences. Changing school, though, isn’t like changing maths class. Children lose their friends, the teachers who know them, and any tailored academic support. In January 2017, independent researchers at the FFT Education Datalab found that of the pupils who left the mainstream roll, only 29 per cent who went to colleges, and 1 per cent who went to an alternative provision or special school, got five good GCSEs.

Off-rolling may improve a school’s results, save money and benefit the brightest pupils, but it hurts the children most in need of a good education. The consultation should hopefully provide an opportunity to put things right.

The case for state boarding schools

My philosophy of education has always been simple and I believe it unites right and left: namely, what wise parents would wish for their child, so the community should wish for all children. It’s a paraphrase of R.H. Tawney, who — being a socialist — said ‘state’ rather than ‘community’. I much prefer ‘community’ since it is an injunction to us all, including to local government, charities and social organisations, as well as to the state and its servants.

I feel this intensely personally, since the community — in the form of a local authority, Camden council in London — was my legal parent for the whole of my childhood. It did a pretty good job, thanks to the wisdom of the manager of my council children’s home, Gladys Baron, who became my surrogate mother. Dispensing a combination of tough love and brilliant strategic judgment about my education and future, she gave me a decent start in life from a ‘home’ where more inmates ended up in prison than at university, and most of whom are now dead. I called her Aunty until the day she died aged 94 and visited her weekly — she was unmarried and had no close relations — in her own final years in a care home.

What changed my destiny was her persuading my social worker, who in turn persuaded the Camden social services committee chairman, that at the age of 11 I should be sent to a boarding school, with the fees paid by the council. She even chose the boarding school: Kingham Hill School, a small institution for 230 boys in the middle of the Cotswolds. The school had previously been a charity home for orphan boys out of London’s East End, founded in 1886 by an unmarried evangelical Christian and former Etonian Tory MP from the Baring family, who took up residence in the neighbouring country house of Daylesford. By 1974, when I arrived off the train from Paddington, dazed by the countryside, it had morphed into an unconventional boarding school, more than half of whose boys were from broken homes and had their fees paid by the Baring Trust or by local authorities. The rest mostly came from military or missionary families.

It gave me the stability of living in the same community for seven years with firm friends and dedicated teachers

It worked, and much as Aunty hoped. Amid the bullying and authoritarianism then characteristic of such schools, there was the stability of living in the same community for seven years with firm friends and some dedicated teachers, one of whom taught me debating and to read the Times, another to act, another to play the school organ, another to visit Paris, and a headmaster who had been to Oxford himself and made me apply although I thought it ludicrously impossible. Underpinning it was a strong ethic of duty, expressed a bit crudely through evangelicalism, but valuable nonetheless.

This experience influenced my whole thinking about education, and in due course many of the reforms of the Blair government. A second-tier policy I promoted as minister and which, in retrospect, I wish I had pushed more boldly was the radical expansion and repurposing of state boarding schools. My inspiration for this was obvious.

There are about 40 state boarding schools in England, and a similar number of privately endowed secondary schools like Kingham Hill run on similar lines. But there should be far more, mixing pupils who want to board and those who need to board, including children drawn from the 60,000 in care at any one time, subject always to the professional judgment of school staff and social workers that this is suitable for each individual. New forms of foster care — covering the holidays and weekends — should be developed to match.

I am aware of only one entirely new state boarding school to have been established in recent years: Holyport in Berkshire, which has Eton as its governing sponsor. Why don’t far more of the historic private boarding schools, rich in assets and boarding expertise, follow suit? And why doesn’t the Charity Commission, which ought to be ensuring that private schools for the wealthy do more to justify their charitable status, encourage this strongly?

And boarding shouldn’t only take place in ‘boarding schools’. Many private schools are part day, part residential, and this should happen more widely in the state sector. I encouraged some new academies to set up boarding houses in the 2000s, but the idea didn’t spread and it needs a new champion.

Private boarding schools, where high fees and social exclusivity are the norm, should also be encouraged to play a bigger social role in terms of their own admissions. I would support a boarding partnership scheme whereby boarding fees for children in care or on the edge of care who would benefit from this residential education are paid by local authorities or the state, provided the private schools cover the cost of the education. I launched a pilot version of such a scheme when in government, and a ‘broadening educational pathways for looked-after children’ scheme has been started by the present government, but the funding involved, and the numbers benefitting, are pitifully small.

Across all UK state and private boarding schools, educating about 70,000 children, only about 600 are currently from a deprived ‘looked after’ background. Most of these are ‘SpringBoarders’ — supported through the Royal National Children’s SpringBoard Foundation, a charity to which the Education Department recently awarded a contract to seek to increase the number radically by developing a new funding, access and partnership model. I hope this now happens. It would be a fitting initiative for the newish Education Secretary, Nadhim Zahawi, an Iraqi Kurdish immigrant who, like me, the son of a Cypriot immigrant, knows the transformational power of education for those starting in this country with few other assets.

No screens, shared bathwater and ugly food: my life in a 1960s prep school

We were allowed one phone call, faint and crackling along the many miles of copper wire which connected Hampshire with Dartmoor. In those days (this was the early 1960s) the operator had to connect it. I had watched those wires, swooping alongside the train which had borne me all that way, wisps of smoke and steam drifting past the window. Now, with the September evening coming on, there was time for a few stilted words in the headmaster’s study with my parents. It would in many ways have been better not to bother, as it only emphasised the distance and the separation. Then it was term.

I don’t want to complain about this. I had begged to go to boarding school because my brother was already there and I would have felt utterly left out and left behind if I had not gone too. And while the whole thing no doubt did me harm, it also did me good, and I shall never be able to disentangle one from the other. In my case I found myself living for much of each year in a handsome and commodious 18th-century gentleman’s house on a Devon hilltop, surrounded by some of the loveliest country in all England.

Dartmoor began at our back door, tawny, dangerous and thrilling. It was not just a view. We went there often. In the other direction, lush, silent valleys led down towards Plymouth and the Tamar, England’s other western frontier. A smaller river, the boisterous Tavy, ran past the grounds. On good days you could see Cornwall and its old brown hills. You could never forget the closeness of the sea, which gives so much to the maritime atmosphere of the West Country. I never felt that the Armada was long ago or Francis Drake was far away.

Our dormitories were named after sea-dogs, beginning with the Cromwellian (and so slightly mistrusted) Robert Blake and ending with the glory and seniority of Nelson. You might describe it as austere luxury. The place was sparklingly clean because we, the pupils, cleaned it thoroughly every day after breakfast. The beds were hard, the dormitories cold, the food (apart from delicious breakfasts, on which I largely survived) ugly, fatty and stodgy. I seldom drank the milk which a benevolent state forced on us each morning, but endangered my teeth each Saturday afternoon with Palm Toffee bars, which would probably be illegal if put on sale today. Even then, in the days of Harold Macmillan, they tried to get us to be interested in eating fruit, but with little success. There was custard, thin and pale. Just as it shouldn’t be. There were indeed prunes, as the great Molesworth describes. If they failed to work then there was syrup of figs dispensed by a matron so stern that I actually believed she was called Gertrude. The poor woman’s name, I found half a century later, was something quite different. I fear that we boys wholly misjudged her.

There were incessant sports and a great deal of compulsory jumping, running and exertion, as well as forced labour, clearing woodlands or picking stones out of newly dug playing fields. There were no cold showers, but there was an unheated swimming pool into which we were expected to leap, a lot. We all learned to swim, if only to keep warm. The most squalid practice, viewed in memory, was having to use other people’s bathwater three times a week. But the more worrying thing is that it seemed quite normal at the time. In fact, almost all of what we did seemed normal at the time.

The most squalid practice, viewed in memory, was having to use other people’s bathwater three times a week

I was neither thrashed nor sexually abused, though I believe others were. One much-liked teacher disappeared abruptly one day, and later turned up in the local police court charged with ‘indecent assault’. The incident caused a kind of revolution in the school, so I’m inclined to think such outrages were rare. Certainly I retained an almost total sexual innocence to the end of my time there. I knew no four-letter words until I was 13, and only discovered the meaning of the word ‘shit’ from a crude inscription on a public lavatory in a park, glimpsed from a train. Yet I could produce a reasonably workmanlike mortice-and-tenon joint and even a dove-tail, and could identify most of the trees and birds in the park which surrounded us, which seems a fair exchange.

As for the cane, I did not want to be beaten, and so took steps to avoid anything which might lead to this. I succeeded, which suggests that there was some sort of order in our ferocious and arbitrary justice system. The closest I came to six of the best was a totalitarian moment when I was given the choice of being whacked or lying that the school food (about which I had been rude) was in fact good. To my lasting shame, I gave in to this terror. I have never forgiven myself.

Really, I was being brought up in the 1930s, by a headmaster whose ideas had been formed before the second world war, when they were thought progressive. There was no television, just the occasional film on a clattering projector. For most of the year, I was free of any screen, a huge benefit.

There was a genteel, well-aged shabbiness about the place which I liked. Where today there would be plastic and chrome, we had wood and brass. We learned a lot from good teachers, some superb. We were supposed to be perpetually busy, and if possible outside, cold and wet. The view seemed to be that if the Devil found work for idle hands, he did so even more skilfully if we were indoors, and more so if we were warm and dry.

Even school skiing trips, supposedly holidays, were preceded by weeks of pre-dawn exercises and filled with organised, supervised group activity. This insistence on being always up and doing was perhaps where the school failed on its own terms, in my case at least. I took quite the wrong lesson from it. I worked out how to disappear when chores were being handed out. I also learned how not to reappear until long after the risk was over. More important still, I did this so unobtrusively that nobody noticed. In the rambling house with its many exits, back stairs and dark corridors, this was quite easy if you put your mind to it, and I did. Hardly anyone ever looked in the library, and even if they did they were unlikely to peer into the deepest corners of it where I sat happily reading for hours as my fellow-pupils toiled or exerted themselves in the drizzle.

One of the many reasons I hated the move, at 13, to a ‘public’ school was that it was too well organised. The bigger school was also more modern, in an unlovable way. It was uglier by far (it looked like a lunatic asylum merged with a waterworks). It was no more comfortable, it was no warmer, and the food was no better. It was just as determined to make me cold and wet and to keep me from my own thoughts. It was obsessed, at the height of the 1960s, with the length of our hair and made us dress in curious garments called ‘sports jackets’, which made us look like miniature bookmakers. But beside all these miseries, it lacked the placid Edwardian calm of my preparatory school. It had instead a feverish, urgent, humourless 1920s feel to it. Bright-eyed prefects would urge us out into the fields to cheer on the House Team. I could not think of any good reason why I should do this. These enthusiasts were as incomprehensible to me as Pacific Islanders.

The school had an actual rule-book (how I wish I had kept a copy) in which the most serious named offence was being late for breakfast. The school line, to be written out 20 times at dawn by malefactors, ran: ‘Few things are more distressing to a well-regulated mind than to see a boy, who ought to know better, disporting himself at improper moments.’ My mind was not well regulated. It never has been, and I did not fit in. We parted company, and I went out into another world, which contained girls but no sports, and where there were no dormitories or dining halls. How I rejoiced.

And yet, more than 30 years after waving a scornful goodbye to boarding school, I found myself in a grey town in Eastern Europe, debating whether to take a dirty, dingy train to a destination I did not especially wish to reach, where things would be a good deal worse than where I was and where phone calls would be hard to make. It was the most important decision of my life, and if I had not done my time at those boarding schools, I think I would have made the wrong choice. I took the train, and it has made all the difference.

Schools portraits: a snapshot of four notable schools

Colville Primary School

Based just off Notting Hill’s Portobello Road, Colville Primary School occupies a Victorian Grade II-listed building that was once a laundry. Today, it accommodates pupils up to the age of 11 who are taught under the school’s ‘three key values’: respect, aspiration and perseverance. Colville also says it believes in the British values of democracy, individual liberty and tolerance. The school’s performance has shot up over the past decade: three years ago, it was rated ‘Outstanding’ by Ofsted. Despite its setting in the heart of London, there’s plenty of area for play — the playground facilities are new, and there’s also a large ball court and running track. The school is digitally savvy, too: Google Classroom is used to set and submit homework. Breakfast is served from 7.45 a.m., while some clubs run until 5.45 p.m. — Colville is a school at which pupils are encouraged to follow their interests well beyond the classroom.

Junior king’s school, canterbury

The feeder of arguably the oldest continuously operating school in the world (education in the grounds of The King’s School has taken place since 597 ad), the nearby Junior King’s School, Canterbury educates 400 pupils aged from three to 13. Some board, but the majority are day pupils. The school is set in a stunning 80-acre countryside spot, only 50 minutes from St Pancras station. It has its own fenced woodland site, where children are able to play and explore as well as take part in bushcraft and scouting. King’s says that academic results take care of themselves when children are well looked-after — all pupils belong to one of four houses which meet every fortnight. When they leave, the vast majority of pupils from the Junior King’s School go on to The King’s School, Canterbury via the Common Entrance exam.

ludgrove

Founded in 1892 by the footballer Arthur Dunn, this Berkshire prep boarding school gives its 190 boys an enormous amount of space in which to compete and play. It is one of the last remaining prep schools to provide full fortnightly boarding, so at the weekends boys can enjoy Ludgrove’s 130 acres of grounds, complete with a nine-hole golf course, swimming pool, 11 pitches, four tennis courts and two squash courts. With several ex-England football captains as former headmasters, Ludgrove’s sporting prowess is hardly surprising: it can field up to 17 teams on one afternoon. The school firmly believes in the link between sporting and academic performance, which is borne out by results: every year, around 70 per cent of the Year 8 cohort go on to Eton, Harrow, Radley and Winchester, with several securing scholarships. Ludgrove excels in knowing its boys, and provides the perfect setting for them to thrive.

Benenden

Based in a Victorian country house in Kent, Benenden houses more than 550 girls from 11 to 18, with some space for day students as well. In 1923, the school was founded by three teachers from Wycombe Abbey, who wanted to build a ‘happy school with personal integrity and service to others always in mind, where everyone would be given the chance to follow her own bent’. Across 250 acres of land just an hour from London, each girl is given ‘a complete education’ (the school’s motto) both in and out of the classroom: students are involved in everything from the Combined Cadet Force to barista training. The facilities are state of the art: the science laboratories — opened by the Princess Royal a decade ago — are some of the most advanced for school-level in the country, and its multi-purpose theatre was opened by Helena Bonham Carter in 2007. Next year, Benenden will open its new school hall and music school.

Advertising feature: Preparing our children for a world that has not yet been imagined

It is our belief at Tadpoles Nursery School that if we want the world to change, we must begin with the teaching of the very young.

Our early years are the moment when our minds are the most open and the most receptive; when we see the world around us with wonder and without judgement and when we are able to ask questions without fear or embarrassment.

Equal Thinking, Ecology and Climate Change, Care and Kindness within our communities — the list goes on — can only be pursued if we educate our children from the very beginning, giving them the imagination, tools and skills at an early age. Allowing them to explore paths not yet taken and ideas without judgment. Neil Postman wrote

‘Children are the living messages we send to a time we will not see’

and it is this exact sentiment that we need to keep in our minds when looking at how we approach every area of our children’s early education.

If we give them the skills to question, to problem solve, to recognise and celebrate their differences, to listen to and to respect their different opinions, to understand and value their different emotions and realise that all emotions are equally valid — rather than putting the emphasis on constant happiness — we will be giving them the skills that will help them to prepare for the future with resilience.

We believe that the most inspiring way of teaching these invaluable lessons is not through ‘forced learning’ but through the art of play. This was recognised in ancient times: ‘Do not keep children to their studies by compulsion but by play’, said Plato. Children’s play has an imaginative and creative flow which leads to discovery and problem solving. The forced learning of phonics and numbers can kill the joys of literacy and numeracy. The use of stories, songs, rhymes and drama, even for daily requests, will imbue a child with a love of words — and the exciting environment around us with its rich mathematical content, can stimulate a love of, and show the child the necessity of, numbers.

With our wonderful ecology garden and forest school area, we focus much of our curriculum base on the natural world around us and everything that it has to offer. Our extended curriculum is ever unfolding and as changing as the seasons, using the natural world to inspire and educate. Ellen MacArthur said ‘In nature, there is no concept of waste. Everything is food for something else’ and we use this approach, not only in the literal sense, when it comes to inspiring and encouraging the development of the children in our care, but when approaching and extending their learning experiences with us. No opportunity to use the world around us is ever wasted.

It is the children who will mould the future of our world but it is for us to instil in them the skills to create that future.

Tadpoles Nursery is a unique, boutique nursery school set in the heart of Chelsea and has been in existence as an early years educational setting, offering our forward-thinking and unique approach to the families of Chelsea, for more than 50 years. We do not believe in ‘static’ learning methods but in ever-evolving and forward-thinking teaching practices, which adapt to each child and their individual needs. We aim to give our children an inspiring, happy, settled and structured environment in which to work and play.

We are now bringing our teaching practices to the children and families of Kensington with a new branch opening in September 2022.

tadpolesnursery.com

Is Boris in denial about the looming economic crisis?

The priority for the UK and other rich democracies is to protect the people of Ukraine from the depredations of Putin’s forces. A close second should be protecting the poorest people in our countries and vital public services from the cancerous impact of soaring inflation, made much worse by the West’s economic warfare against Putin’s Russia.

The most basic costs of living are soaring. And that means a devastating recession that has already begun for all those but the richest. This blow to living standards will be the worst in living memory, more pernicious than the impact of either the banking crisis or Covid.

Talking to ministers and MPs, it is clear to me that they as yet fail to appreciate the scale of the economic shock that is upon us.

And ahead of the Chancellor’s spring statement in a fortnight – his annual economic health check – there will inevitably be significant tension between Rishi Sunak and the prime minister about how much to spend to protect living standards and the most important public services from the ravages of inflation.

It is not clear to me that the government has quite yet grasped the scale of the economic challenge

This is a very different debate from the one about how much to spend to protect workers and the economy from the impact of Covid, because the virus was thought to be a temporary phenomenon, whereas the reconfiguration of the global economy forced by the invasion of Ukraine will be permanent.

The immediate challenge is that embargoes on Russian oil, gas, wheat, minerals, assorted commodities, and associated disruption to important transport routes, are massively pushing up the prices of the basics of life – which hit those on middle-to-low incomes hardest.

In the space of not much more than a year, inflation in the UK has risen from less than 1 per cent to 5.5 per cent and may nudge 10 per cent in coming months. As just one example, from last autumn to the coming autumn, typical costs for a UK family to light and heat their homes are set to rise around £1,800.

It’s true that the Treasury has already committed more than £9 billion to easing the pain of the energy price rises. But that delivers subsidies of just £350 for most homes, less than a fifth of the increased costs.

But perhaps the biggest dilemma for the government will be how and whether to protect public services from inflation, or how to honour promises to tackle the NHS’s record backlog, remediate damage to schooling from Covid, and increase defence spending.

The important point is that in the Treasury’s spending review of just a few months ago, the new departmental budgets for the next three years were set in cash. When the Chancellor claimed to be increasing resources for public services in real terms, that claim was based on inflation forecasts that were far too low and are ancient history. As just one simple example, the soaring price of fuel will add hundreds of millions of pounds per annum to the costs of the armed forces and Ministry of Defence.

But the biggest potential squeeze on funds available, for schools, hospitals and the army, will be the impact of inflation on its salaries and pension bill. In the simplest terms, every extra pound given to a nurse to protect his or her pay from the impact of cost-of-living rises is a pound not available to expedite a hip operation or a cancer scan.

So probably the biggest decision for the Chancellor and PM is whether to shelter the pay of nurses, doctors, teachers and other public sector workers from the pain of rising prices, whether to increase their pay in line with or above inflation, or whether to force a huge squeeze in living standards on them.

And if their pay is protected from inflation, that will mean – in the health service alone – that there will be billions of pounds less to spend on operations and diagnosis.

There is a related crisis of purpose for the Bank of England and other central banks, which were already set on a course to raise interest rates, to suppress rising inflation.

But much of the inflation cannot be stopped. And the increase in the cost of money will only make the living standards crisis worse for poor people, and will increase the government’s interest bill, further depriving it of funds for public services.

As I say, it is not clear to me that the government has quite yet grasped the scale of the economic challenge that is upon it. When it does, I doubt the Ukraine-generated unity we’ve seen within parliament, and within the ruling Tory Party, will withstand the pressure.

The raw politics of how much a Conservative government should be borrowing to help public services and poor people will be back with a vengeance.

Why would the Saudis bail out Biden?

Is Saudi Arabia shunning Washington? Mohammed bin Salman has reportedly been refusing to phone Joe Biden, who wants the kingdom to turn on its oil taps as the West desperately seeks alternatives to the Russian energy market.

Riyadh – the world’s largest oil exporter – has so far failed to accommodate Washington’s pleas. Ahead of the Russian invasion in mid-February, the US asked the Opec+ cartel – of which Saudi Arabia is the most important member – to produce more oil to slow the already rising prices. Opec+ stood firm, and said they would increase production by 400,000 barrels a day in April, a rise agreed before the threat of a Russian invasion of Ukraine. The UAE told the FT it hopes to boost production, but the Saudis are yet to give the green light.

MBS could offer Biden a quid pro quo: more oil for recognition

There are grievances. Joe Biden has – unlike Trump – refused to speak directly to the crown prince Mohammed bin Salman and hasn’t recognised him as Saudi Arabia’s de facto leader (that is, until he needed his oil). Biden’s administration believes that MBS was involved in the murder of the Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018, so has been dealing with the elderly Saudi king instead.

In 2019, the then presidential nominee said he wanted to treat Saudi Arabia as a ‘pariah state’. That’s now looking like a dim move. Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner courted a close relationship with MBS, and the Trump administration largely looked the other way over Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen. The result was a stable partnership with the world’s largest oil exporter. Biden, meanwhile, came to office promising to end ‘all American support for offensive operations in the war in Yemen’. In practice, this meant cutting off 75 per cent of Saudi Arabia’s weapons imports. The UAE and Saudi Arabia have come under missile fire from Iran-backed Yemeni Houthi rebels over the past few weeks, and have received no support from the US.

Meanwhile, American diplomats are still eager to resuscitate the nuclear deal with Iran. It’s worth remembering that Biden was in charge of foreign policy when he was Obama’s vice president. In the Middle East, he’s picking up where the Obama administration left off: forging a better friendship with Iran and ostracising Saudi Arabia. American diplomats have been in Vienna for months of talks about a new nuclear deal with the Iranians. If signed, Iran would be able to sell far more oil to the US, a blow for Saudi Arabia’s exports. The deal wouldn’t even destroy Iran’s ability to build nuclear weapons, as Riyadh hopes, since it would only be effective for 15 years and wouldn’t ban all Iranian nuclear capabilities.

A richer Iran can fund Saudi Arabia’s enemies across the Middle East: the Sunni Arab states – like Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and the UAE – know this and have formed an Arab-Israeli alliance against Iran in the past two years. Why would Mohammed bin Salman grant Biden’s requests for more oil if the US is about to breathe life into a rival oil exporter, and flood Saudi Arabia’s enemies with cash?

As well as a growing stand-off with the US, Saudi Arabia has economic reasons not to comply. If the US and Europe wean themselves off Russian oil without a backstop in place, Riyadh will be able to sell its oil at an incredibly high price. Why would they want to lower it? Soaring oil prices will give MBS’s grand reform plans – Vision 2030 – a financial boost. The crown jewel of his plans is Neom – the utopian new city by the Red Sea which will feature a 105-mile hyperloop called The Line – which had been struggling to get off the ground, as Max Jeffery wrote for Coffee House last year. But the Saudi executives from the megaproject visiting New York next month might look like better friends – and a better investment – if Riyadh’s hose could rescue American consumers.

For now, Saudi Arabia seems to be helping Moscow, not Washington. By not producing more oil, the kingdom is making it harder for western nations to justify halting exports from Russia with speed. The Kremlin-Riyadh friendship is a brittle one: the two countries had an acrimonious and somewhat forgotten production war in March 2020 just as coronavirus hit. And why would Saudi Arabia look kindly on a Russian president who rescued Iran’s biggest puppet – Bashar al-Assad – during the Syrian civil war?

If the West bans imports from Russia without a back-up in place, Saudi Arabia could plug the gap. If Joe Biden continues to ostracise Saudi Arabia, Americans will feel the pain at the petrol pump. After several years of coldness from the West, Mohammed bin Salman might be about to get more recognition and more investment. He has Western power where he wants it.

The SNP won’t be happy until Boris is charged with war crimes

Blood streams through Ukraine. Tears run through parliament. At PMQs today, numerous members urged Boris to show more compassion towards Ukraine’s refugees.

Poland has already taken 1.2 million. Barely a thousand have been received here, as Boris confirmed, but the number will rise sharply. Leading the pro-refugee campaign was the SNP’s Ian Blackford who seems to represent every region on earth apart from his own constituency. In a venomous speech he charged the home secretary, Priti Patel, with imposing a ‘hostile environment’ on refugees for ‘ideological’ reasons. Well, well. No one could accuse the SNP of embracing xenophobia for political gain.

Blackford lambasted the government for ‘putting up barriers and bureaucracy’. Yet he dreams of installing a barbed-wire frontier at Berwick-upon-Tweed and dividing Britain into two trading areas.

Boris was clear. He expects and wants a vast influx from Ukraine. Hundreds of thousands, he declared, will arrive through the family reunion scheme. He sees newcomers as wholly advantageous. His cabinet agrees and he cited their personal heritage. Dominic Raab, Priti Patel and he himself are all descended from emigres who escaped persecution to settle in Britain.

No one could accuse the SNP of embracing xenophobia for political gain

He’s already won this argument. Everyone in parliament wants more and more arrivals. The only snag is speed. They can’t get here fast enough. An SNP member complained that two Ukrainian runaways had been asked to wait for 13 days in Hungary while their biometric details were processed. That pushed Boris over the edge.

‘Can he pass me the details of the case he mentions?’ he said, offering to become their personal travel courier.

He vowed that he will ‘move heaven and earth’ to bring the exiles in from eastern Europe, and he again flaunted the internationalist character of his administration.

‘We are unlike any other in our understanding of what refugees can give and their benefit to this country.’

No downsides, apparently. He will also establish ‘routes by which the whole country can offer a welcome to people fleeing war.’

That sounds interesting. The first to use the scheme will be those MPs who called loudest for the new arrivals to be welcomed. Isn’t that how it works? Most MPs have two publicly subsidised homes to choose from. Bunk beds can be installed. Attics can be cheaply converted. Marquees can pop up in gardens to take the overspill from the main residence. And any late arrivals can crash out on the sofa for a month or two. The Commons website should post a daily chart to reveal how many families each MP is sheltering.

Ian Blackford will find this useful. As he said of Ukrainians, ‘these numbers don’t lie. These numbers tell a devastating truth.’

His Hebridean ranch will soon be teeming with displaced families. Brendan O’Hara, his SNP colleague, raised the stakes and spoke about a post-war reckoning. He predicts that Boris ‘will stand accused of lacking the one thing the Ukrainian people needed most – basic humanity.’

The SNP won’t be happy until Boris is charged with war-crimes.

Ed Davey trounced the SNP. He ordered Boris to send the army across the channel. Field Marshal Davey has analysed the military position with his characteristic pragmatism and gusto, and he believes that ground forces are needed to get the refugees out ‘swiftly and safely’. One question. Should the invading UK forces cross into Ukrainian territory and risk bumping into Russian paratroopers? Perhaps the great commander didn’t think that detail mattered. Either way, he didn’t mention it. Davey’s invasion would be the first deployment of British troops in Europe since D-Day. Not that he plans to go with them, of course. He’s too good a soldier for that.

Sturgeon: Nato shouldn’t rule out no-fly zone

Fresh from apologising for the persecution of witches in the sixteenth century, Nicola Sturgeon has now jumped on to the next big challenge. You’d have thought the energy, cost-of-living and health crises might keep the First Minister occupied, not to mention the various issues around Scotland’s schools, transport links and criminal justice system.

Not a bit of it. For the nationalist-in-chief has found a new cause to involve herself in: international relations, an area specifically reserved for Westminster. Despite having no powers, mandate or army, Sturgeon today decided to take a swipe at Nato, using an interview with ITV to argue the defence bloc should review the idea of a ‘no-fly zone’ over Ukraine on a ‘day to day basis.’

This idea, attractive as it may seem to those appalled by Putin’s invasion, has been ruled out by virtually all western policymakers, on the grounds that it would necessitate Russian jets being shot down, were they to enter Ukrainian airspace. This would likely constitute an act of war with a nuclear state, potentially triggering the most gruesome kind of atomic apocalypse. Mr S isn’t surprised to see Sturgeon calling for an unfeasible and unenforceable policy; coherent thinking has never been a necessity in a party that last month claimed the UK would pay its pensioners’ benefits post-independence.

What is surprising is the Scottish government’s apparent desire to dictate Nato policy, when the SNP were in favour of pulling Scotland out of the military alliance and its ‘collective defence’ clause as recently as, er, 2012. The pillar of Nato’s strength has always been the American nuclear deterrent; quite the irony then that current SNP policy is to remove the country’s nuclear weapons if Scotland ever votes for independence.

Advocating unilateral nuclear disarmament at the same time as hinting at action that could precipitate World War Three: talk about joined-up government. Mr S isn’t exactly sure how surrendering the British nuclear arsenal would help Ukraine in this situation; presumably President Putin is expected to respond in kind too?

Given Sturgeon’s inability to run a functioning health system, Steerpike would forgive Nato’s finest in Brussels if they were to disregard her remarks. Good thing she doesn’t actually have any role in foreign or defence policy – no matter how much she tries…

Can Nato help Ukraine without provoking Putin?

Nato is trying to walk a tightrope in Ukraine. It wants the Russian invasion to be defeated, as the US joint chiefs of staff declaration that ‘We will make a second Afghanistan for Russia’ in Ukraine makes clear. But it also doesn’t want to do things that would enable Moscow to escalate the conflict on the basis that Nato has entered the war.

This dilemma is behind the problem with the Polish MIGs

This dilemma is behind the problem with the Polish MIGs. Fighter jets are both offensive and defensive weapons and if they are flown into Ukraine from Nato airspace, things get very tricky. This is why Washington has rejected the Polish scheme to hand them over to the US and then have the Americans get them into Ukraine. (Indeed, it would have been far better for this whole thing not to have been done so publicly. If the negotiations had all been done in secret, it might have been possible to slip the planes into Ukraine in a deniable way, as has happened in the past.

But denying Russia air superiority is also crucial. At the moment, the air space over Ukraine is still contested – which is one of the things slowing Putin’s military down. The UK decision to offer Ukraine Star Streak missiles, just announced by Ben Wallace in the Commons, is an attempt to prevent Russia gaining air superiority even if the delivery of MIGs continues to be impossible.

We are no two weeks into this war and it is clear that the Russians have been denied the quick victory that the Kremlin appears to have anticipated. But continuing Ukrainian resistance will require finding ways to carry on getting supplies into the country, even as the Russians advance.

PMQs: Johnson struggles to defend refugee policy

Today’s Prime Minister’s Questions clash between Sir Keir Starmer and Boris Johnson focused on the domestic implications of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The Labour leader started by calling on Johnson to force Chancellor Rishi Sunak into a U-turn on his policy of a £200 loan to help with energy prices.

Starmer’s argument was that this loan had been developed on the assumption that prices were going to fall, but Ukraine had changed that. Johnson argued that Starmer would be ‘absolutely out of his mind’ to be arguing that the Chancellor should U-turn on the help he was already offering. That wasn’t what Starmer was saying: he was arguing that the ‘help’ would actually cause more pain because people would be required to pay back the loan when they were struggling even more with their bills. ‘We will see how long that position lasts,’ he retorted.

Starmer also asked for a windfall tax on the profits of energy companies, accusing the Prime Minister of ‘protecting energy profits, not working people’. He also expressed theatrical astonishment with the Prime Minister as he ridiculed Labour for changing tack on nuclear power and for refusing, as he claimed, to invest in nuclear. ‘Oh come off it!’ he expostulated. ‘Labour is pro-nuclear. This Prime Minister can’t get a single brick laid of a new nuclear plant!’

These exchanges were designed to show that the government doesn’t have a plan for coping with the cost of living. ‘Britain can’t afford another crisis like this,’ Starmer argued. It is indeed going to be a very uncomfortable year for the Conservatives as the cost of living goes up and up. But the more immediately politically awkward exchanges came later and were on refugees. SNP leader Ian Blackford started the complaints on the matter, accusing Priti Patel of incompetence and of presiding over one of the worst responses in Europe.

Johnson’s answer sounded very pre-written, starting with the line that ‘everybody sympathises with the plight of refugees: this government wants to do everything we can’. He then ignored Blackford’s second question in which he accused Patel of blocking people fleeing war crimes ‘with endless paperwork’, and claimed, to some jeering from the opposition benches, that this government has an unparalleled record on refugees.

He made this assertion once again when he found himself being questioned by someone rather more politically potent: not Blackford, who tends to unite the Tories in derision, but former Chief Whip and Northern Ireland Secretary Julian Smith, who asked:

I commend the Prime Minister’s response to this Ukrainian crisis, but I think people across the country are genuinely concerned on our response on refugees, on the bureaucracy, on the tone of our response. He has shown with vaccines that government change really comes from the very top. Please can I urge him to look again on resetting our policy and taking control of a more humane approach to those women and men fleeing from Ukraine.

Johnson was initially defensive, referring Smith to his answer to Blackford, before adding:

I think there is a huge opportunity now for us to do more, which is why my right hon. friend the Secretary of State for Levelling Up will be setting out a route by which the British people, not just the family reunion route which can run into the hundreds of thousands, but also a route by which everybody in this country can offer a home to people fleeing Ukraine…

Though he was insistent that the UK government is out in front on refugees, that response suggests the Prime Minister hasn’t overlooked the worries Smith set out. Indeed he would, to use his own language, be ‘absolutely out of his mind’ if he did so.

The solution, it seems, is to use Michael Gove to clear up another ministerial mess, something he has made a career out of. But as Smith pointed out, government successes come from the top, and they tend to be successes because the person at the very top knows what their policy is. Today’s session didn’t give us much reassurance on that.

Ukraine should think twice before joining the EU

Volodymyr Zelensky certainly made big waves when he addressed the European parliament. In the ensuing debate last week, many MEPs made emotional calls for the EU to show its solidarity with Ukraine by accepting its application made a couple of days earlier for full EU membership. So did those outside: nine Baltic and eastern European states immediately supported the project, and Poland, the EU member with most in common with Ukraine and hitherto the most generous to its refugees, called bluntly for membership to be not only granted but fast-tracked.

However, the fires of enthusiasm were quickly and unceremoniously doused by Brussels, with Germany and the Netherlands pouring cold water on the plan. Neither Ukraine, nor Moldova and Georgia, which both applied hard on its heels, should receive special treatment; all should queue up and patiently wait their turn. A depressing rebuff? Not necessarily. Actually Ukraine may well have good reason to be grateful.

The EU is hardly a military powerhouse

For one thing, however euphoric the protestations about the European family and the shouts of ‘Slava Ukraini!’ that rang through the Berlaymont building in recent days, it’s not easy to see that EU membership would actually benefit Ukraine much in its difficulties with Russia.

The EU is hardly a military powerhouse. True, it has sanctioned Russia economically. But get matters in perspective. Russia desperately needs hard cash to continue its pulverising of Ukrainian cities. What are EU countries doing? They are paying it a very useful $300 million (£230 million) a day in exchange for gas. Brussels has ruled out putting a stop to this any time soon. True, it talks optimistically of reducing its systemic dependence on Russian oil and gas over the coming months, but that is by-the-by. By then in all likelihood the present war will be over. Meanwhile Putin could hardly have hoped for better support. The EU has assured him that, for the moment, it prefers to protect its own comfortable lifestyle by continuing to suck greedily at the Russian gas teat, and that it will not cut off his convenient source of cash for some little time, during which he can doubtless explore other markets. Some support for a member of the European family in desperate need for protection from a totalitarian bully busily engaged in shelling its civilians.

And even in the long term, it’s difficult to see much guarantee that the EU will consistently support Ukraine or even be particularly concerned to stand up for its interests. True, EU member states in eastern Europe with hard experience of Soviet control, such as Poland, may have a healthy mistrust of Russia’s pretensions. But the richer western EU countries, who largely control the organisation, on the whole don’t. If Germany or France, the leaders and paymasters of the EU, find it in their financial or political interest to appease Russia, they will; witness Germany’s refusal before the invasion to say or do anything that would seriously discompose Vladimir Putin or put a spanner in the works of Germany’s humming economy. And if this happens there is every chance that the EU will play along, as it has in the past.

The fact that the EU has apparently chosen not to single out Ukraine, and instead pointedly put its application on a par with those of Georgia and Moldova, itself says quite a lot. Both these latter countries have refused to be full-blooded in their support of Ukraine against the invader. Admittedly this is partly because of fear of the bear looking over their shoulder: both have suffered invasion and bullying; both have chunks of territory brazenly occupied by Russia (Abkhazia and South Ossetia in Georgia; Transnistria in Moldova). But only partly so. In Georgia the ruling Georgian Dream party has a reputation for Russophilia, and there is a noticeable pro-Russian minority in Moldova. And in any case, an EU prepared to incorporate two countries that, for whatever reason, feel unable to antagonise Russia is not necessarily the most comfortable billet for Ukraine.

This is, of course, to say nothing of the other imponderables of possible EU membership. Ukraine already has what is effectively a free trade agreement with the EU, to which before the invasion some 40 per cent of its exports – mainly primary products and machinery – regularly went; if so, the trade case for entry is not enormously strong. One also suspects that with free movement and a well-educated population, EU membership would spark an immediate and debilitating talent drain to western Europe. However beautiful the restored Great Gate of Kiev may be, Paris, Amsterdam or Frankfurt would clearly be a pull for the young and ambitious in an economy where per capita GDP is less than $5,000 (£3,800).

An ideologically westward-looking Ukrainian minded to see Europe in terms of the EU could do worse than look at the slightly strained relations between the EU and Ukraine’s closest cultural relatives, the people of Poland. Warsaw, with its own long history of bullying by the bear in the east, has consistently found itself under attack from Brussels on account of its refusal to knuckle under to the EU’s bullying tendencies. It has fought back manfully at what it sees as interference with its constitutional and internal affairs by an overbearing European Commission and European Court. Would Ukraine, with its if anything stronger nationalism, its social conservatism and the strong influence of its Catholic and Orthodox churches, find its path much smoother? One rather doubts it.

The logic is clear. If and when Ukraine survives its present onslaught, it should think at least three times before submitting to an increasingly illiberal EU yoke. There is nothing wrong with a large European country of 45 million choosing to make its way independently. In the case of the people of Ukraine, indeed, it is almost certainly in their long-term interest.

Mail man changes his ‘Russian-sounding’ name

Sanctions, boycotts, bans, penalties of all kind: there’s no end to the punishments being slapped on Moscow. But amid the frantic rush of institutions and individuals to distance themselves from Russia, some seem to be somewhat overstepping the mark.

The Cardiff Philharmonic has today cancelled an all-Tchaikovsky programme as ‘inappropriate at this time’; Russian conductor Valery Gergiev was sacked last week by the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra for failing to condemn Putin. In Italy, the University of Milano-Bicocca has been forced to backtrack after trying to cancel a Dostoevsky course while at least three MPs in the UK have suggested stripping Russians in Britain of their citizenship.

But now one man at the Daily Mail has done his own unique form of protest. Oliver Smith – previously known as Oleg Vishnepolsky – has taken to LinkedIn to explain he is now in the process of legally changing his name in protest at the ‘invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent atrocities being committed by the Russian government.’

Smith, who is the chief technology officer at the Mail’s parent company DMG Media, said that the move was because ‘my family and I were expelled from Soviet Russia over 40 years ago for alleged anti-Soviet and “anti-Russian” propaganda.’ He added: ‘I hold great respect for all cultures, but with everything that is happening in Ukraine this change of name is very important to me.’

The move has prompted a mixed reaction on the popular social media platform, with some complaining that he was lumping in all Russian culture with the actions of a kleptocratic fascist. Smith doubled down on the move in the comments underneath his LinkedIn post, claiming ‘You can change the world, sometimes by a little step forward’ and ‘I don’t change who I am. I change perception of who I am.’ After someone referenced the cancellation of the Dostoevsky course, Smith hit back:

The Russian culture, if you know history and Dostoevsky who you reference, has always been about misery and human suffering. Don’t impose that misery on other nations.

The renaming of family titles is nothing new of course. During the Great War, the royal family changed their surname from its Germanic roots to the British ‘Windsor’, prompting the Kaiser’s remark that he looked forward to attending a performance of Shakespeare’s ‘Merry Wives of Saxe-Coburg’ at the first opportunity.

Given the spirit of the times, perhaps Smith and his Mail colleagues will rename Le Carré’s work as ‘The Northcliffe House’ instead?

Ukrainian ambassador: my wife couldn’t get a visa

It’s been a pretty dreadful few weeks for Vadym Prystaiko. Kiev’s man in London has been doing his best to secure extra resources for his country’s struggle against the Russian invasion, though the calls of President Zelensky for a ‘no fly zone’ have gone unheeded. As if he didn’t have enough on his plate, Prystaiko has been summoned for a meeting of the Home Affairs Select Committee meeting, amid the ongoing crisis about visas for Ukrainian refugees.

Prystaiko has become something of a familiar figure in parliament in recent days: he received a standing ovation from MPs before last week’s Prime Minister’s Questions and popped up again in the public gallery yesterday’s before Zelensky’s speech to both chambers. Today’s appearance was less adulatory as Prystaiko detailed the Home Office’s foot-dragging over the issue of allowing Ukranians into the country, even before the war.

He told MPs that there have been no end of ‘bureaucratic hassles’ for years for his fellow citizens coming to the UK, with his own wife initially being denied a visa to join him – despite him being his nation’s representative. If Prystaiko’s wife had a hard time getting here in times of peace, what chance those ‘ordinary’ people fleeing Kiev in the face of Putin’s war machine?

In defence of mutually assured destruction

The slow return of the 1980s has reached its logical conclusion. The prospect of nuclear annihilation is haunting our nightmares once again. Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has been marked by a willingness to engage in blatant nuclear sabre-rattling of a sort not seen since the end of the Cold War.

From his statement that anyone ‘interfering from outside’ would ‘face consequences greater than any you have faced in history’ to his placing Russia’s nuclear forces on ‘a special combat duty regime’, Putin’s strategy has been to threaten nuclear war to keep the West out of what he sees as his business.

But these threats don’t mean that Putin is about to send missiles soaring over Europe at any moment. Nuclear analyst Pavel Podvig believes that the ‘special combat duty’ is nothing more than an elevated state of vigilance rather than an instruction to make Russia’s system ‘ready to fire’. Putin’s words are instead an attempt to disincentivise certain western behaviours.

The question of whether he would actually use these weapons is in some senses irrelevant; what matters is that we can’t be sure he wouldn’t. In much the same way that a bank teller faced with an armed robber is unlikely to push the issue of whether he’s willing to pull the trigger, Nato is unwilling to initiate a potential military conflict.

The greatest point of danger is when one side believes it can ‘win’ a nuclear exchange

To carry the analogy forward, two men with loaded weapons would be careful to interact politely and predictably, rather than making aggressive and unexpected motions.

Mutually assured destruction works because both sides believe that the use of nuclear weapons on their part would be met in kind, with any conflict entering an irreversible escalation. Because the rational response to a nuclear launch is a nuclear launch, there is no incentive to engage in one. And because conventional conflict raises the risk of nuclear war if the parties are unbalanced, there is a strong incentive to avoid that too.

In other words, so long as both of our men are sitting with their weapons drawn and loaded, neither wants to fire. Putin himself has observed that nuclear war ‘would be a global disaster for humanity’ and a thing to avoid, but that if provoked ‘I must ask myself: why would we want a world without Russia?’.

Rather than signalling imminent conflict, Putin’s rhetoric is a reminder that we should be aware of this balance. Those concerned about his sabre-rattling can find some comfort in the Russian statement on its nuclear doctrine, which lists the circumstances under which the state would consider using its nuclear weapons: the launch of ballistic missiles targeting Russia, the use of weapons of mass destruction within its territory, conventional forces threatening the existence of the Russian state, or an attempt to ‘decapitate’ Russia’s nuclear forces.

Of course, a degree of ambiguity over when and why these weapons would be used gives the threat of their deployment greater weight, and the existence of a doctrine hasn’t stopped speculation over other circumstances when they might see use. Some analysts – and the 2018 US Nuclear Posture Review – have speculated that Russia could use a strategy of ‘escalate-to-de-escalate’, deploying nuclear weapons or their threat to cement battlefield advantage or terminate a conflict. This is not contained within the Russian strategy document, although suspicious readers could find things to dislike in the phrase ‘preventing the escalation of hostilities and their termination on terms acceptable’.

It is the existence of this ambiguity, though, and a desire to avoid accidental escalation that has led Nato to firmly commit to avoiding direct conflict with Russia in Ukraine. And for all the talk, neither Russia nor America has put its forces on standby for imminent use. America has more command and control aircraft making flights, ensuring that its command chains would survive an attempt at a pre-emptive strike. Russia is making sure that its facilities are staffed.

The logic of mutually assured destruction can be counter-intuitive, but in some circumstances these actions can serve to make conflict less likely. The greatest point of danger is when one side believes it can ‘win’ a nuclear exchange – through missile defence systems, pre-emptive strikes, or other measures – destabilising the delicate equilibrium. Measures that reduce that temptation help keep things predictable.

None of this is to say you should be particularly delighted about peace being maintained by the threat of nuclear Armageddon. If nothing else, the United States refuses to adopt a ‘no first use’ stance, and the Russians have a policy that could see them sending warheads over in response to faulty equipment telling Moscow the Americans have started a war. Mutually assured destruction may have had its successes, but it has also had a string of near misses.

For all the rhetoric, nobody wants an accidental exchange of nuclear weapons. It would be by far the most embarrassing way for a sentient species to go extinct. Nato and Russia have taken sensible steps during this war to avoid the risk of escalation, keeping forces away from a hair-trigger stance, maintaining lines for urgent communication, and postponing missile tests.

That Putin might use nuclear weapons in extremis is less relevant than the fact that this uncertainty means we should never find directly confrunt Russia. As he himself has said: ‘it would probably mean the end of our civilization’.

Engels mustn’t fall

Should a 3.5 metre high Soviet statue of Karl Marx’s collaborator and patron Friedrich Engels – brought over from Ukraine five years ago – stay up in central Manchester? The concrete likeness of communism’s co-founder, dating from 1970, lorded over Mala Pereshchepina, a village a few hours drive from Kharkiv, until 2015. In the aftermath of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the stoking of pro-Russian insurgents in Donbas, Ukraine decreed that all Soviet era symbols be removed – and Marxism’s co-founder was felled there, only to rise again in Manchester.

This Engels from Ukraine was not erected to celebrate Anti-Dühring, his 1877 polemic against the wrong kind of socialist. It and thousands like it throughout the former Soviet Union and communist Central and Eastern Europe were there to show who the masters were: the Communist party, and that they intended to stay in power.

The statue then is a physical manifestation of a wicked system which brought about massive suffering, death, and even in its most benign periods extinguished human autonomy in a cloak of collective drabness. Its very existence is a symbol of Soviet power over Ukraine, probably something we don’t want to celebrate, especially in light of Russia’s current invasion.

History shows all too clearly that the Soviet Union did not turn into the paradise Engels envisioned

When it was moved to Manchester in 2017 some asked what was going on. Dan Hannan said: ‘Communism killed 100 million people. And we’re putting up a statue of Engels’. That sentiment may be a tad unfair as Engels died in 1895 and communists weren’t in a position to engage in mass killing until 1917. But bad ideas have consequences, for which some of the blame must be apportioned to Engels.

With the invasion of Ukraine, objections to the statue and what it means are being taken more seriously. HOME – a publicly-funded arts centre in the heart of Manchester opened in 2015 at a cost of £25 million – outside of which Engels stands declared last week that:

‘In light of the illegal invasion of Ukraine by the Russian army, we are in discussions with the co-commissioners of the artwork Manchester International Festival and the artist Phil Collins about how best to respond’.

The art centre later clarified that they were not suggesting the sculpture should be taken down, but rather that it should be contextualised in the now fashionable way. Yet this forgets the reason why Engels was put on display in the first place. His statue in Manchester was never intended as a homage to the Soviet Union. Instead, it was Engels’ links to Manchester that led to it being rehoused there. Engels’ parents owned a textile mill in Salford, and the young Engels was sent there to manage it. His Manchester observations are the basis of ‘The Condition of the Working Class in England’, one of his most famous works.

Of course, history shows all too clearly that the Soviet Union did not turn into the paradise Engels envisioned in these writings. So, knowing what we know now about communism, does it really make sense to add a new sign ‘explaining’ Engels statue? If so, the obvious option would be to put up plaques detailing the role of such statues in the USSR. Perhaps, too, these could offer an exposition of what was carried out in the name of Engels’ ideology, including the Holodomor, Ukraine’s 1932-33 terror famine.

Maybe, though, there is another way of sending up Engels? Engels’s book ‘The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State’ is, bizarrely, a paean to meat eating. Adopting the ideas of American anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan, Engels argues that prehistoric man progresses from various stages of savagery through barbarism to civilisation and that progression from one stage to the next is marked by changing diet. In Engels’ schema when humanity was in its infancy, changing diet played the role that changing economic systems played in Marx’s more familiar trajectory of history.

Humanity, we are told, comes down from the trees of lower stage savagery to be tempted by a diet of ‘crabs, mussels and other aquatic animals’ – and thus moves up to middle stage savagery. Gradually meat eating enters our diet, first through hunting and then animal husbandry; there is even a cannibalistic interregnum. As meat eating increases, we move through various pre-historical stages and gradually become more civilised. At least that is Engels’ argument: ‘the plentiful supply of milk and meat accounts perhaps for the superior development of the Aryan and Semitic races. It is a fact that the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico, who are reduced to an almost entirely vegetarian diet, have a smaller brain…’

Engels – albeit on the basis of bad anthropology and worse science – would have been no fan of vegetarianism, let alone veganism. If the current public location of the Engels’ statue is no longer deemed acceptable, it could be moved to be the centrepiece of a very blokey American style steak restaurant celebrating the pleasures of red meat. Taking Engels down would forever be used as a precedent by the iconoclasts of our age. Let’s not give them that argument: much better to contextualise the rascal.

Why is Britain so useless at helping Ukrainian refugees?

Some MPs were in tears yesterday when President Volodymyr Zelensky addressed the House of Commons, and understandably so, given the soaring rhetoric and bravery of a man who knows his days on earth could be numbered.

One kind interpretation is that the caseworkers at the Home Office haven’t been trained sufficiently for them to use the initiative

But across Westminster over the past few days, MPs and their constituency teams have also been crying tears of frustration at the Home Office’s handling of the visa application process. Not only has there been intense confusion between the different arms of government about how many routes there are for refugees – with Home Secretary Priti Patel claiming she was creating a third one, only for No. 10 and other ministerial colleagues to insist there were only two routes and that wasn’t changing. Then there is the problem with the visa application centres: on Monday Patel said one had been set up en route to Calais, which turned out not to be true, with refugees still being told to go to Brussels or Paris. ‘En route’ could be Lille, more than 70 miles from Calais, where a new centre is being set up (although the Eurostar stops at Lille).

There has also been a bizarre inflexibility on the part of the Home Office when it comes to the existing routes. Constituency caseworkers for MPs tell me refugees have been asked for documents, which people fleeing a war zone would never think to carry with them. Others have been surprised when asked to post documents to an office in Wandsworth. The system doesn’t seem even to be able to cope with the internet going down mid-application, which is hardly uncommon in a war zone, and perhaps still more frustratingly there are cases where the system itself has crashed. ‘I actually told someone today to stop telling me the computer says no,’ complains one.

One kind interpretation is that the caseworkers at the Home Office haven’t been trained sufficiently for them to use the initiative when it comes to people fleeing for their lives from a war zone. Others are relieved that the community sponsorship route is now being managed by another ministry: Michael Gove’s Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Department, with a new minister, Richard Harrington, working between Home Office and Gove’s department to try to improve things.

The government has struggled to work out what its overall policy on Ukrainian refugees is. Does it want to help as many as possible to come here, or does it want to help the countries closest to Ukraine support people before – or if ever – they are able to return home? Given the UK cannot grant a no-fly zone, and given any additional support may have to be deniable (and therefore not the sort of thing ministers brief to newspapers), it might be wise to take some time to work out what the policy on refugees really is, who is in charge, and how it is going to be implemented properly.

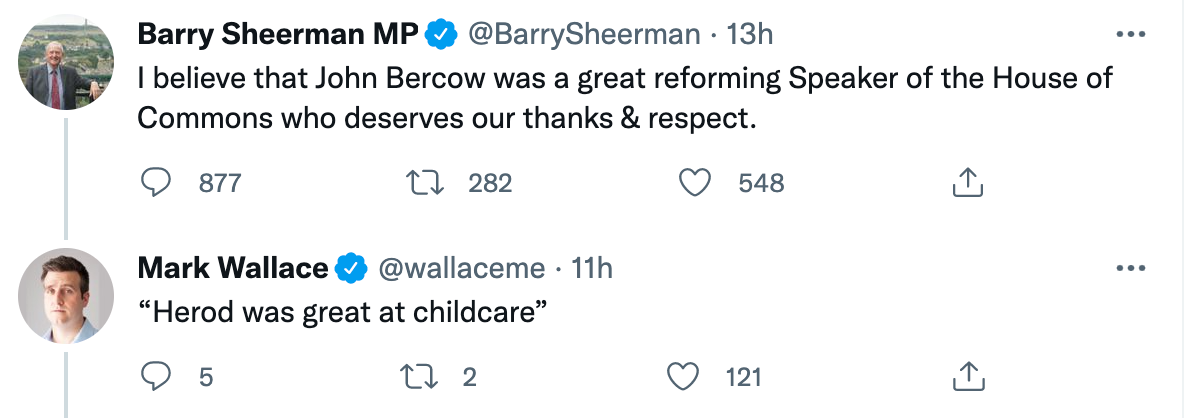

Eight embarrassed Bercow backers

The verdict is in and it’s not good for John Bercow. Yesterday finally saw the publication of the independent expert panel report into his behaviour as Commons Speaker, with 21 separate allegations of bullying being upheld against the former Buckingham MP. The conclusions of the report were damning: Bercow was judged to be a ‘serial bully’ and a ‘liar’ who ‘repeatedly and extensively’ bullied staff and exhibited ‘behaviour which had no place in any workplace.’

It will be seen as vindication for the members of staff who spoke out against Bercow for years before yesterday’s publication. It’s also damning of those who continued to prop up and cheer on the former Speaker in office, purely on the cynical grounds of derailing the Brexit process.

Allegations of Bercow’s bullying behaviour were aired by the BBC’s Newsnight programme as early as May 2018. Five months later he faced calls to quit after an independent report by Dame Laura Cox found that harassment and bullying had been tolerated and concealed for years. It led to the resignation of three Tory MPs from the representation group chaired by Bercow, with the trio citing his handling of bullying and sexual harassment allegations in parliament as the reason for doing so.

Despite all this, Bercow continued for a long time to be the toast of the FBPE (follow back, pro EU) Twitter brigade. Many still supported him after he quit as Speaker in 2019, despite two highly-respected former members of parliamentary staff submitting formal complaints about his behaviour in January 2020.

Now though, any hopes of a political comeback appear to have been finally extinguished; his membership of the Labour party was suspended five hours after the report came out. Mr S has rounded up the best of the worst Bercow-backing cheerleaders who egged him on, even after the first allegations had been aired…

Margaret Beckett

The grand dame of the Labour party rather let the cat out of the bag back in October 2018. Following the investigation by Dame Laura Cox, Beckett told BBC Radio Five Live that Labour should overlook Bercow’s alleged behaviour to secure a meaningful vote for MPs on Brexit. She said:

So much for workers’ rights.Abuse is terrible, it should be stopped, behaviour should change anyway, whether the Speaker goes or not. But yes, if it comes to the constitutional future of this country, the most difficult decision we have made, not since the war but possibly, certainly in all our lifetimes, hundreds of years, yes it trumps bad behaviour.

James O’Brien

After Bercow ripped up parliamentary procedure to allow a vote on the Grieve amendment in January 2019, the author of ‘How to be Right’ weighed in with this finely-aged classic. Bercow has appeared several times as a guest on O’Brien’s show in recent years, with his friendly ‘grilling‘ on the bullying claims back in February 2020 being notably more gentle than the treatment which O’Brien metes out to others who call in to his show.

David Lammy

A series of gushing tributes greeted the news that Bercow was to depart the Speakership in late 2019. A classic of the genre was this offering by ardent Remainiac and self-styled peoples’ champion David Lammy, now recast as Sir Keir Starmer’s shadow Foreign Secretary.

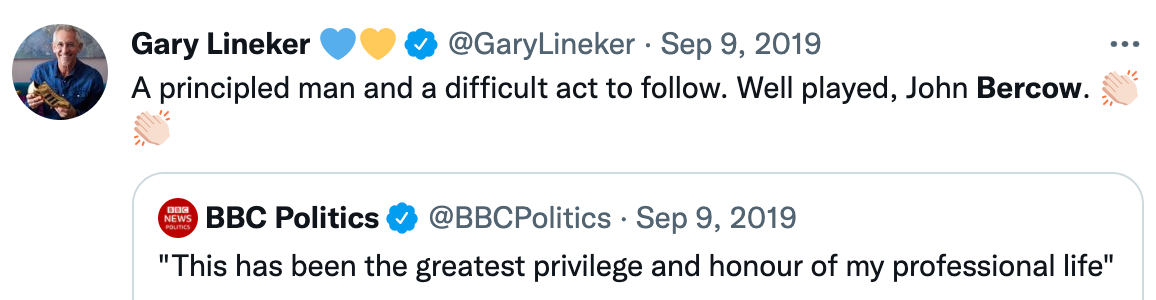

Gary Lineker

Where there is discord, may we bring harmony. And no Remainer harmony would be complete without the voice of the king of centrist dads Gary Lineker. For him, Bercow was both ‘principled’ and a ‘difficult act to follow’; Mr S awaits to see if the latter’s successor, Lindsay Hoyle, will also be the subject of an 89-page report into bullying accusations.

Alastair Campbell

Bercow’s departure in November 2019 prompted a raft of valedictory tributes. He might not have got a peerage but at least he got an interview in GQ magazine with Alastair Campbell. Who else knows more about a ‘big heart’ than the king of spin? Tellingly, among Bercow’s characteristics which Campbell listed approvingly was his party trick of being a ‘good mimic’, something he put to good effect in belittling his staff, according to yesterday’s report.

Dawn Butler

Given his penchant for ripping up parliamentary procedure, it perhaps should not have come as a surprise in February 2020 that the government declined to award Bercow a peerage, making him the first Speaker in 230 years not to have been given one. Nevertheless a row blew up, midway through the Labour leadership contest. Dawn Butler, then a candidate for the deputy post, went on Sky News and said: