-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Might Macron’s future rest with the England rugby team?

After two rounds of the Six Nations, France is the only unbeaten team. Their victory against Ireland in a ferocious encounter in Paris on Saturday evening keeps them on course for the championship title.

The last time France won the Six Nations crown was in 2010. The decade that followed was not kind to the national team. One might say their decline mirrored that of the country in general. They became a laughing stock, finishing bottom of the Six Nations in 2013 and suffering embarrassing defeats to the likes of Tonga and Fiji. Everything about the French team was amateur — their preparation, their fitness, their technique — compared to the clinical professionalism of their Six Nations rivals such as England, Ireland and Wales.

But Les Bleus are back. They travel to Edinburgh on Saturday week to face the inconsistent Scots and then it’s off to Cardiff to play a Wales side that also blows hot and cold. If France is victorious in both of those games they will have the opportunity to win the title (and with it the Grand Slam) in their final match, which is not only in Paris but also against the team that everyone in the championship loves to beat: England.

Few French fans will have their fingers crossed for a title triumph as tightly as Emmanuel Macron. The President likes his sport, particularly football, and he has not been shy in the past about exploiting its popularity with the masses for political gain. He was in Russia in July 2018 when France played Croatia in the World Cup Final. France won, and didn’t Macron let the world know it. The photo of him celebrating in the stand, punching the air in delight, adorned the world’s newspapers and internet sites the next day.

England has dominated France in recent years, winning seven of their last ten encounters

Success in the Six Nations would sit very well with Macron. The first round of the presidential election is three weeks after the championship and it doesn’t take much imagination to envisage how he would spin the win to his advantage. France is on the up, Macron will say, not just the rugby team but the country at large.

To no one’s great surprise the government last week suggested that the Covid Passport will be dropped at the end of March, just in time for the election, although of course any such move will be based on health considerations not political ones. Regardless, the French will be delighted with its demise, a sign that life is slowly returning to normal. Throw in a first Six Nations title in 12 years, and which self-respecting French person wouldn’t have a little spring in their step as they entered the polling booth?

There are precedents in how sport has influenced political elections. For example, in the run-up to the British general election in 1970, Harold Wilson was on course to be returned to power. One poll had his Labour party holding a 12 per cent lead over Ted Heath’s Tories. But four days before the election West Germany staged a stirring comeback in the quarter-final of the World Cup to knock out holders England 3-2.

Heath emulated the Germans. Was it a case of the public taking out their disappointment on Labour? In his memoirs the Labour defence minister at the time, Denis Healey, wrote that before he called the election Wilson ‘asked us to consider whether the government would suffer if the England footballers were defeated on the eve of polling day?’

There is another reason why Macron will be desperate for French success in the Six Nations. The team is, to coin a cliche, a ‘celebration of diversity’. Along with the gnarled men of the deep south, such as the hooker Julien Marchand, born in the shadow of the Pyrenees, there is also Demba Bamba, raised on a housing estate in the Paris suburb of Saint-Denis, and Yoram Moefana, who arrived in France aged 13 from the Pacific island of Futuna. Against Ireland on Saturday the French team — their eyes wide and their chests out — sang La Marseillaise with gusto, along with 80,000 fans in the Stade de France, many of them waving French Tricolores. It was a stark contrast to what was happening a few miles south in the centre of Paris, where policemen used tear gas to disperse protesters from the ‘Convoy of Liberty’.

Macron’s pitch will be that the French rugby team — like the football squad — embodies the very best of the Republic. Éric Zemmour, on the other hand, is the candidate who wants to end all immigration and ban parents from giving their children foreign-sounding first names. How will that help French sport?

Will Macron be in the crowd on March 19 for ‘Le Crunch’ against England? He’s attended high profile rugby events before, such as the final of the French domestic championship in June 2019 between Toulouse and Clermont-Ferrand. But that didn’t quite go according to plan. The public, presented with a rare opportunity to let their President know what they thought of him, whistled and booed as he was introduced to the players on the pitch.

A Six Nations crowd, being more corporate and middle-class, will probably be more respectful. Many of them, one suspects, are Macron supporters. Nonetheless it would be a risk to turn up for the Six Nations decider in person; particularly as it’s against Perfidious Albion, the country Macron loves to loathe. Wouldn’t it be typical of the English to pee on the President’s parade?

England has dominated France in recent years, winning seven of their last ten encounters, and were they to make it eight — and perhaps in the process snatch the Six Nations title from under French noses — Macron could suffer politically. Nobody likes to be linked to a loser.

Merde, the French might mutter, not only did England emerge from lockdown months before us but now they’ve put one over us on the rugby field. Who’s the ‘clown’ now?

The West is doing Putin’s work for him

Ukraine, as is periodically observed, means borderland. Geography will forever influence its destiny as an independent state. With tensions between East and West again rising, however, Kiev might well conclude that Ukraine is more accurately translated as ‘on the margins’.

Foreign leaders and ministers have, to be sure, been punctilious in making courtesy visits to President Zelensky and his team before or after paying court to President Putin in Moscow. But it must now be crystal clear to Kiev that — in a conflict essentially centred on Ukraine, though actually about much more — its western champions have at best considered Ukraine’s interests as secondary to the pursuit of the main quarrel with Russia, often not considering them at all.

How else to explain the flurry of developments over the past week? As Volodymyr Zelensky pressed on heroically with his message of keeping calm and carrying on, and most Ukrainians — quite astonishingly — did just that, the US and the UK together amplified their warnings of a Russian invasion. It is now not just ‘imminent”, apparently, but scheduled for as early as Wednesday.

Nor did they stop at upping the already heated rhetoric, which had been briefly paused at the end of January. They passed on to action — action that has a direct impact on Ukraine. Both countries extended their previously announced withdrawal of diplomats, adding calls for all US and UK nationals to leave Ukraine while there were still commercial routes out. ‘Remember Kabul airport?’ Asked the UK’s second-in-command at the Ministry of Defence, James Heappey, during an interview on the BBC Today programme. Well, he went on, the Taliban had had no airpower to speak of; imagine how it could be with missiles and the like. Oh, and by the way, he strongly inferred, the RAF won’t be risking their lives to get you out.

It is hard to believe that any of this is in the West’s interests

A dozen countries have now instructed or recommended their nationals to leave. The Netherlands, with memories of almost 200 Dutch deaths in the MH17 disaster, announced that KLM was stopping all flights to Ukraine. Others are expected to follow suit.

There are bleak, but confident predictions, that international insurance companies will cease cover for companies operating in Ukraine, as well as for visitors. That will effectively leave Ukraine not just physically cut off but branded an unsafe destination — a label that will be harder to lose than gain. A UK Foreign Office travel advisory has the effect of banning most travel, as it renders UK travel insurance policies invalid.

And the bad news kept coming. Having announced with great fanfare the dispatch of 2,000 shoulder-launched anti-tank missiles, and a 30-strong group of ‘elite troops’ to show them how to use them, the same minister who treated breakfasting Britons to a horrific vision of air strikes disclosed that all trainers were being withdrawn ‘over the weekend’. The United States is doing the same.

Of course, one interpretation might be that these military departures were envisaged as a tiny olive branch to Moscow, designed to reassure Russia that the West was not about to wage war over, or at least in, Ukraine. But the message this sends to Kiev is far clearer: Ukraine is on its own. It may be a ‘valued partner’ of Nato — as described by the Secretary General, Jens Stoltenberg, last month — but it is not a Nato member, and as such, does not benefit from the protection of Article 5.

The same message that Ukraine is now on its own was conveyed with the announcement of other US and UK withdrawals: this time from the OSCE monitoring mission in eastern Ukraine. Again, other countries are likely to follow, but not — it has to be hoped — all, as the OSCE, which monitors the fitful ceasefire, is the only international group that just about commands enough trust on all sides to be effective.

On 28 January, Zelensky gave a press conference in Kiev for the international press, which highlighted two main messages clearly intended for foreign governments. The first, since repeated several times, was that western alarmism risked having a counterproductive effect on Ukraine and that, if it wanted to help Ukraine, the US in particular should pipe down. The second was that the West’s dire warnings had killed foreign investment and Ukraine urgently needed economic help. For a president who had started with well-thought-out plans for the country’s development, and had had some success in drumming up interest, this turn of events is little short of catastrophic.

The risk now is that, in precipitating a showdown with Russia over the future of European security arrangements, the US and UK are inflicting near-fatal damage on the state they have treated as their protege since the Euromaidan uprising of 2014.

If you hold the view that a successful, prosperous and democratic Ukraine presents an existential threat to Putin’s Russia, then ruining that country, as the West currently risks doing, amounts to nothing more than doing Putin’s dirty work for him. Even if you don’t hold that view — I don’t, I believe a successful Ukraine is in Russia’s interests — an isolated, insecure and impoverished Ukraine stands to cost the West even more over the long term than it already has.

Many, if not all the gains of the past decade or so, in terms of democratic freedoms, economic growth and a healthy sense of national identity, risk being lost. But perhaps the greatest loss could be the political stability and cohesion that Zelensky’s landslide election victory promised. It should be noted that the huge demonstrations on the streets of Ukraine’s major cities this weekend, which received extensive coverage in the international media as expressions of national unity, were initiated by the nationalist right. This was not the platform on which Zelensky, who is of Jewish descent, campaigned; it is a spectre from Ukraine’s past that could yet be revived.

It is hard to believe that any of this is in the West’s interests. Some European countries and some individuals seem to realise this and are staying, demonstratively, in Ukraine. But many aren’t. Do western leaders really not see that, by their words and their actions, they are well on their way to sacrificing Ukraine, this time in the supposedly greater cause of opposing Russia?

Is Brooklyn Beckham fooling us all?

Brooklyn Beckham, the eldest son of David and Victoria, has launched a new television show Cookin’ with Brooklyn which allegedly took £70,000 and a team of 62 professionals to create.

The result is an 8-minute episode that produced a fish-finger sandwich. Brooklyn oversees an assembly of chefs preparing the ingredients, he looks into the camera, totally deadpan and informs his audience, ‘With sandwiches you can go so many different ways. It really does help to be creative’.

Is this show the epitome of everything that’s wrong with our society, as some have claimed?

Brooklyn Beckham is rich. He is the amusing celebrity-child kind of rich. The sort that spends winters skiing in Whistler and Spring bobbing around the Caribbean on a super-yacht with his godfather Elton John. The kind that falls in love with an heiress to a billion dollar fortune and spends £9 million on his ‘starter home’ in Beverly Hills.

It was inevitable that the time would come when Brooklyn would have to venture out into the big bad world and make his own way. If you can call it that.

Brooklyn has gone big. His lack of any obvious talent was as nothing to his inherited ability to have doors opened for him. This makes people angry. As we sit around wondering how to we’ll cope with inflation and the cost of living crisis, the spectacle of Brooklyn pretending on TV to make a career as something other than a celebrity — for the sake, ultimately, of furthering his utterly unearned fame — grates on many of us.

But we may as well shake our fists at the sky. It may be unfair, but it is undeniable: the children of the celebrity rich have more advantages in a world where online name recognition is everything. It is why Prince Harry, a man with fewer GCSE’s than your average supermarket worker, was paid £112 million by Netflix to make documentaries. And it is why Brooklyn Beckham is a published author, has appeared on the cover of Vogue, shot a campaign for Burberry and been paid £1 million to front a SuperDry campaign all before turning 23.

Brooklyn fancied himself as a photographer, and aged 17 he got himself a photography book deal. The photos were a collection of the world ‘through his eyes’. His writing was, er, succinct: ‘elephants in kenya. So hard to photograph but incredible to see’. He also featured a fishing trip with his family: ‘I didn’t catch anything – annoying but still fun’.

He also dabbled in environmental activism, inspired no doubt by the elephants. In Kenya, he met Sir David Attenborough. Shortly after, he did a SuperDry campaign supporting sustainability. Promoting the campaign coincided with COP26. When asked in an interview what he made of the event, Brooklyn looked blank until the journalist explained it was a ‘big climate conference in Glasgow’.

Ever the professional, he remained unfazed: ‘Every day I am trying to read and learn more’.

Then came cooking. There was the bacon and egg sandwich he cooked for an audience of nine million on Good Morning America followed by aVogue tutorial in which he cooked creamy, cheesy pasta for his lactose intolerant fiancé. In his culinary arsenal he also has the squish burger (a standard burger you squish just before eating) and the now infamous fish finger sarnie.

To publicly set yourself up to fail on such a grand scale is, dare I say it, admirable. To invite such widespread ridicule is brave.

Is Brooklyn actually secretly in on the joke, as people often thought Paris Hilton was? Is he trying to reveal how far you can go with very little talent but the right parents in our modern, utterly non-meritocratic society?

I fear not. His lack of self awareness seems absolute — the gloriously unfiltered product of being famous from birth.

Of course £70,000 for an eight minute cooking tutorial is insane and outrageous. But don’t blame Brooklyn. The sooner we come to terms with the truth the sooner we can make peace with it. The celebrity super rich can spin gold out of anything – even fish fingers.

Prince Harry’s ‘Americanisms’ are no such thing

Ever since Prince Harry moved to Los Angeles, royal commentators with an interest in the English language have been watching what he says. He may have walked the walk but has he also started to talk the talk? In October 2020, the Mail ran a piece headed ‘Prince Harry calls opening the bonnet ‘popping the hood’ as he picks up Americanisms after seven months in US with Meghan Markle’. In May 2021, the Express announced ‘Prince Harry swaps Queen’s English for Americanisms in desperate bid to “be liked”‘, gasping that ‘Prince Harry has dropped elements of his cut-glass English accent in favour of Americanisms’. Just last week, as Harry spoke about his mother’s work combating the stigma around HIV and AIDS, some people felt their hackles rise regarding his choice of words: ‘I feel obligated to try and continue [her work] as much as possible’. Why use the American ‘obligated’ when the British ‘obliged’ is right there?

Harry has also been criticised for scattering Americanisms throughout his Archewell podcast, addressing his audience as ‘you guys’ and describing things as ‘awesome’. But anyone thinking all this is evidence of a recent change to his language hasn’t been paying attention: Harry has never had a ‘cut glass’ accent and his idiolect – his personal way of speaking – owes more to the English public school system than to his American wife. If you’ve ever found yourself in close proximity to a group of modern public school boys, what strikes you is not their adherence to the norms of received pronunciation and vocabulary but their keenness to distance themselves from them. Frankly, talking posh isn’t cool.

The young upper classes have been early adopters of US slang for generations. Think of Bertie Wooster, whose zippy lines are almost as full of American slang as they are of English:

His way of speaking owes more to the English public school system than to his American wife

Here, with a sniff like the tearing of a piece of calico, she buried the bean in her hands, and broke into what are called uncontrollable sobs.

— P. G. Wodehouse, The Code of The Woosters, 1938

‘Bean’ (meaning ‘head’) feels traditionally British, perhaps reminding us of ‘old bean’. It’s actually US slang from the early 20th century (related to ‘bean ball”, a baseball term for a ball pitched at the batter’s head), as are countless other beloved Woosterisms, from ‘on the blink’ to ‘spill the beans’. Even that quintessentially English phrase ‘stiff upper lip’ comes from America, its first recorded use being in the Massachusetts Spy of 1815.

Wodehouse’s contribution to the Americanisation of British English gets some commentators rather hot under the collar (another Americanism). In his impassioned plea for resistance, That’s The Way it Crumbles, the writer Matthew Engel laments: ‘If there is a Typhoid Mary in the Americanisation epidemic of the 1920s the name of the No.1 carrier must be the creator of Bertie Wooster and Jeeves.’

What’s more, for Engel, the fight against the Americanisation of English is as much about culture as it is about language: if Brits mindlessly import American words into their dialect, we risk unconsciously adopting American ideas along with them. Hence, Engel argues, the Americanisation of the language goes hand in hand with the Americanisation of the culture, playing a part in everything from Thatcherism to Blairism to people losing interest in the countryside.

But we’d be wrong to assume that this fear of cultural invasion runs only one way. Long before he published his great American dictionary in 1806, Noah Webster argued that establishing linguistic independence from the British was as critical for Americans as political independence.

Language reform, for Webster, was a chance to build egalitarian principles into the very way Americans spoke and wrote. Hence spelling would be simplified – no more unnecessary ‘u’s in ‘honor’ and ‘humor’, no more Frenchified ‘-re’ endings to ‘meter’ and ‘center’. Irregularities would be removed where possible. And as well as fostering a new and enlightened national identity, these changes would support the American printing industry: new books for a new country. Even today there are Americans concerned about the influence of British English: the US website www.notoneoffbritishisms.com attempts to keep track of what it refers to as the ‘Britishism invasion’.

While America’s greater size and cultural heft can make it feel as if the influence is all one way, actually Brits are holding their own. The cultural behemoth of the Harry Potter industry has played a large part in this: while the books were lightly edited for their American audience, care was taken to keep their essential Britishness: they evoke a rather old-fashioned and romantic boarding school world and the British language is part of the charm. One slightly surprising result of this is the US adoption of the British word ‘ginger’ to describe red hair, thanks to Harry’s side-kick, hapless red-head Ron Weasley.

And what of Meghan in all this? The royal watchers who look out for Americanisms in Harry’s language now he’s in the States were equally keen to spot Britishisms from Meghan when she was over here. The results were…underwhelming. Claims that Meghan had started speaking with a British accent were largely exaggerated and quickly debunked. But, had she stayed here longer, it’s highly likely that her both her accent and vocabulary would have changed through a process known as accommodation, that unconscious imitation which so many of us do when speaking to somebody with a different accent. As it is, the sole reported Britishism she has taken back to the States with her is a tendency to say ‘oh dahling!’ without the ‘r’.

Corbynistas trolled by The Crown

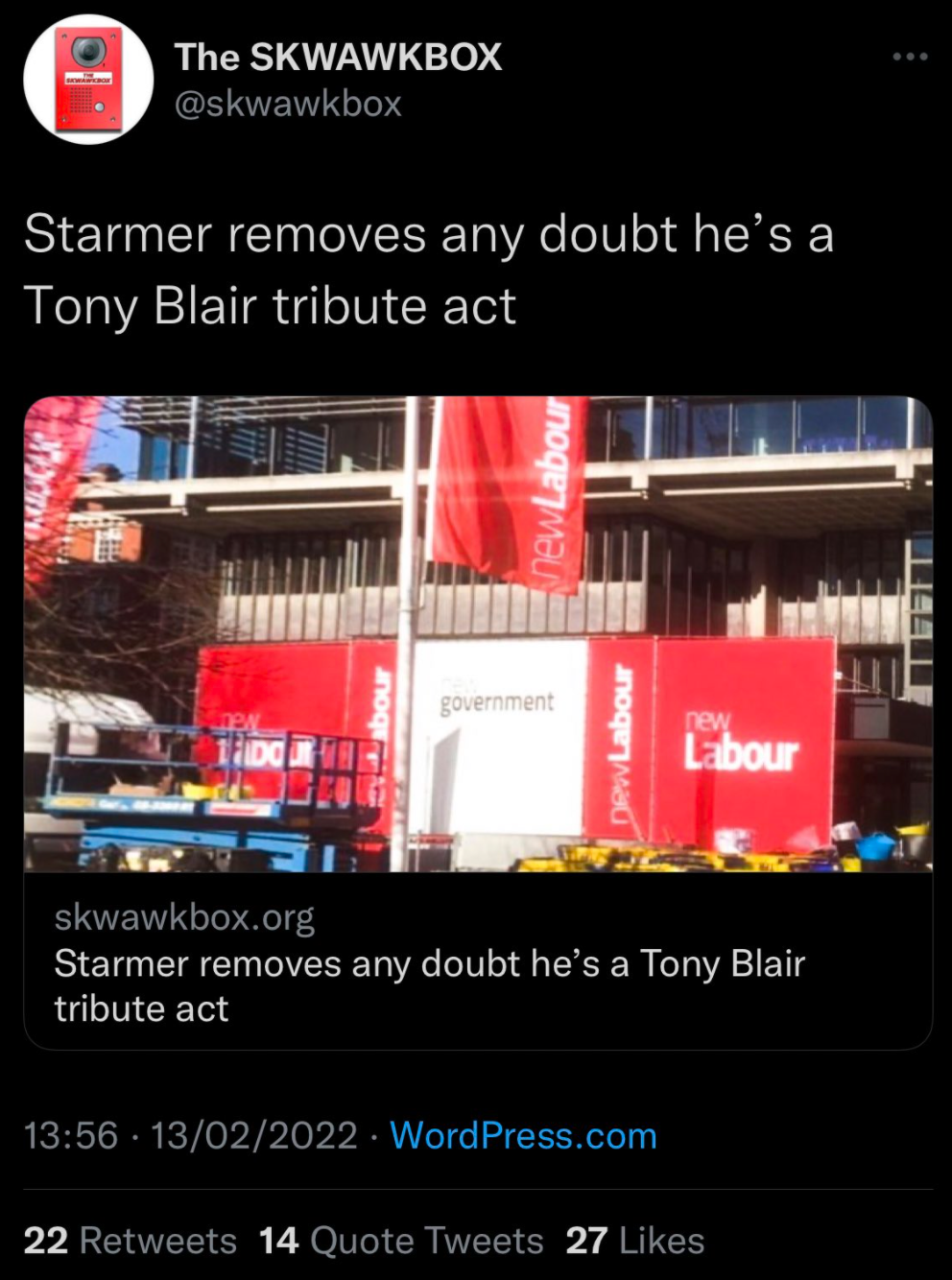

Jeremy Corbyn’s fans were never the sharpest tools in the box. But even by Corbynista standards, the egg-heads over at Skwawkbox do a disservice to the Magic Grandpa with their constant half-baked witterings. Since Labour was crushed at the 2019 election, Mr S hasn’t had to care much about what the left-wing websites says about anything, given Sir Keir Starmer’s preference for briefing newspapers, not disreputable blogs. But even he couldn’t resist writing about the latest conspiracy which the slavish socialists have now fallen for, hook, line and sinker.

For Netflix series The Crown is currently shooting in Westminster, with season five expected to cover the monarchy in the 1990s, with the Queen’s annus horribilis, Diana’s death and all the rest of it. As part of this, the cast has taken over the QEII Centre next by Parliament Square, to recreate the scenes of Tony Blair celebrating his victory there on the morning of the 1997 general election. Numerous ‘New Labour’ signs and banners have been erected around the site; cue much droll commentary about whether Starmer really has been studying the Blair playbook too closely.

Unfortunately, Skwawkbox displayed their usual journalistic genius by taking such claims at face value. Without bothering to even ascertain the true reason for the flags, the Corbynista blog duly ran an article headlined: ‘Starmer removes any doubt he’s a Tony Blair tribute act.’ Like Pravda without the prose, the blog breathlessly claimed ‘Keir Starmer’s latest advertising makes it absolutely clear that he’s presenting himself as Tony Blair Mk II.’ It concluded that use of the ‘discredited’ New Labour brand was the final proof that Starmer would return Labour to the bad old election-winning days, ending its dispatch by sneering that Sir Keir thinks ‘that what the public wants is a new version of the man many would like to see on trial in the Hague for war crimes.’

After it was pointed out to the hard-of-thinking bloggers that, er, the event was in fact unrelated to anything to do with the Labour party, a correction was quietly posted claiming that ‘Some have suggested this may be a set for a new series of The Crown. Starmer is still a Blair tribute act.’ After further online mockery, the title was changed too so that it now reads ‘Blair tribute act said to be The Crown set.’

For Skwawkbox, it seems that things can only get better.

Vince Cable slammed over China (again)

Oh dear. Britain’s onetime favourite ‘liberal’ is at it again. Mr S has chartered the sad decline of Vince Cable in recent months from household name to Beijing’s useful idiot. The onetime Lib Dem leader is one of the few mainstream politicians to claim China’s treatment of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang does not amount to genocide, as part of his bid for the UK to develop closer ties with the country. This is despite reports that the Uyghur persecution there meets all five UN criteria for genocide. Indeed Layla Moran, the party’s foreign affairs spokesman, issued a very public slapdown last June when Cable first made these claims.

Now though, an unchastened Cable has gone even further. In comments made on Friday at the National Liberal Club at a panel discussion on China, the former Lib Dem leader was asked a question by Rahima Mahmut of the World Uyghur Congress about the situation there. Cable, who was speaking at the event to raise funds for the party’s local candidate Edward Lucas, responded strongly:

They did what I did, they read through a lot of the documentation, alleging, quote ‘genocide’ in Xinjiang and they said “What is happening there is dreadful but to call it genocide is absolutely, completely wrong.” This is nothing whatever to do with the kind of horrors that happened in the Holocaust or Rwanda. This is a totally different situation. This is a brutal, probably, overreaction to a terrorist movement and that we should of course criticise it and condemn it. But this is not genocide or anything remotely like it.

He then bemoaned how and he others had been ‘pilloried’ for making such remarks. Poor Vince. He added that describing the situation in Xinjiang as ‘genocide’ is ‘not helpful, ultimately to the Uyghur cause’ – something which didn’t go down well with Mahmut, who does not know the fate of her nine siblings there. She told Mr S:

I can’t remember the last time I felt so angry, patronised and belittled. Cable clearly knows very little about China, the history of the persecution of Uyghurs and the definition of genocide. He merely repeated the Communist party’s lies about how their suppression of my people is a result of extremism. Cable seems to think he knows better than hundreds of legal scholars who agree that the criteria for genocide are met because the CCP is systematically preventing our women from having children. Vince Cable is a genocide denier, plain and simple. It is hard to believe gestures of solidarity while this man remains within the Liberal Democrats.

It’s worth remembering too that Cable doesn’t just echo the CCP’s lines on Xinjiang. Last month at the Oxford Union he effectively victim-blamed protestors in Hong Kong for Beijing’s clampdown on democracy there, claiming that:

Those people in Hong Kong who, in the name of democracy and free speech, started throwing Molotov cocktails at the police and vandalising their legislature did their little bit to kill Hong Kong democracy because it was very clear what the rules of the game were and the Chinese were not in any way dishonest or unclear about what was permissible.

Such comments received a glowing write up from one section of the press at least – China’s state-run network CTGN. Given that Cable these days doesn’t seem too keen on the ‘liberal’ or ‘democrat’ aspects of his party, Steerpike wonders just what it will take for his fellow knight Sir Ed Davey to kick him out of the party. A Lib Dem spokesperson told Mr S that:

Vince has many views which the party has always valued, but on this he is wrong. There is clear cut evidence of a genocide in Xinjiang Province, as the Uyghur Tribunal found, and we cannot stay silent while the Chinese government commits atrocities against the Uyghurs. That starts with the UK government recognising that a genocide is taking place, something which the Conservatives have shamefully failed to do.

Let’s hope it’s Vince who will be staying silent in future, eh?

Sunday shows round-up: Invasion of Ukraine ‘entirely possible’

The situation on Ukraine’s borders now appears to many as though it is the calm before the inevitable storm. In the Sunday Times, Defence Secretary Ben Wallace has even criticised some western actors for creating ‘a whiff of Munich in the air’, referencing Neville Chamberlain’s infamous 1938 negotiations with Nazi Germany. Trevor Phillips interviewed the Northern Ireland Secretary Brandon Lewis, who said in no uncertain terms that Ukraine would have to brace itself for the worst:

Boris Johnson will ‘successfully fight the next general election’

Ukraine’s turmoil has been the only story of the year so far that has been able to rival partygate’s rigid grip on the political scene. Downing Street has confirmed that over 50 people have been sent a questionnaire by the Metropolitan Police over the affair, including the Prime Minister. Lewis told Sophie Raworth that the PM had his full support:

Yvette Cooper: Starmer is not a ‘pro-war’ Labour leader

Raworth was also joined by the shadow home secretary Yvette Cooper. She asked Cooper about remarks made by Cooper’s predecessor Diane Abbott, who claimed that Sir Keir Starmer was ‘pro-war’ and would have sent British troops into Vietnam in the 1960s. Cooper rebutted Abbott’s claims:

Rosie Duffield ‘should be free from abuse’

Raworth bought up the case of Canterbury MP Rosie Duffield, who has said that she is on the verge of leaving the Labour party over the levels of abuse she has received for refusing to toe the line on gender issues, notably including her comment that ‘only women have a cervix’:

Former head of the police watchdog: Cressida Dick was ‘a very talented leader’

And finally, Zoe Billingham, who served for many years as Her Majesty’s Inspector of Constabulary, stuck up for the outgoing Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Cressida Dick. Dick was essentially forced to resign her role on Friday after it became clear that she no longer enjoyed the confidence of London Mayor Sadiq Khan:

Can Edinburgh really blame Henry Dundas for the evils of slavery?

In March 2021, in the aftermath of the Black Lives Matters protests, Edinburgh City Council approved plans to install a new plaque on the Melville monument to Henry Dundas in St Andrew Square, Edinburgh. Part of the text referred to ‘the more than half-a-million Africans whose enslavement was a consequence of Henry Dundas’s actions.’ Now, bitter controversy rages in the Scottish press about the historical accuracy of those words and whether Dundas deserves to be held solely responsible for the evils of continuing the slave trade.

A leading figure in the government of Prime Minister William Pitt, Dundas (later Lord Melville) was Secretary of State for the Home Office, Secretary of War, and First Lord of the Admiralty. He spoke during parliamentary debates on abolition of the British slave trade, including in 1792 when he proposed an amendment for gradual delay when the House of Commons was set to yet again reject William Wilberforce’s proposal for immediate abolition. The year before, the House had comprehensively rejected by 163 votes to 88 Wilberforce’s motion to introduce a similar bill. As a result of Dundas’s intervention in 1792, for the first time the House of Commons voted to abolish the slave trade, but to do so gradually, though there was debate over the eventual end date and it was stalled in the Lords. Final abolition of the British slave trade did not take place until 1807.

The words on the plaque hold Dundas exclusively accountable for this delay, which has been opposed by prominent historians. In the Herald in January 2021, Professor Sir Tom Devine denounced the wording as ‘bad history’ since it presented Dundas as some ‘kind of superman, a titan who single-handedly managed to produce this extraordinary historical result of postponing abolition.’ Rather than blame Dundas, Devine pointed to key political, economic, and military forces that meant no British government ‘would want to get abolition over the line’ in that period.

Those key forces included the violent insurrection of enslaved people in the French colony of Saint-Domingue and the immense shock the rebellion caused in British society; war with France and the strategic importance of the West Indies in that conflict; the great economic benefit for Britain derived from the trade in cotton, and for Scotland, dried salted fish; and unrelenting opposition from the House of Lords and King George III.

Writing for the History Reclaimed website, Professor Guy Rowlands also judged the plaque ‘deeply misleading’ and ‘egregiously unfair’ in seeking to make Dundas ‘carry the blame, and carry it alone, for the continuation of the slave trade.’

In contrast, and in line with the wording on the plaque, some historians have attempted to hold Dundas mainly – and in some cases – solely responsible for the delay to abolition. In an article for the Scottish Historical Review, Dr Stephen Mullen writes that Dundas’s insertion of the word ‘gradual’ into the abolition motion, ‘delayed the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade from 1792 until 1807’. In a blogpost he ramped up his claims by asserting he was ‘the great delayer’ and:

‘The activist position (that Henry Dundas delayed abolition) is not one based upon “rewriting history” but the arguments are broadly consistent with the published work of academic historians going back to 1975.’

Edinburgh City Council have a moral duty to amend or remove the plaque as soon as possible

Defending the plaque, Mullen has further alleged on Twitter that historians of slavery and abolition ‘are unequivocal that Dundas delayed abolition. The plaque wording reflects that orthodoxy’.

But my examination of the key works of the historians mentioned by Mullen casts very considerable doubt on his claims and those enshrined in the Edinburgh plaque.

The first problem is Mullen’s misuse of previous scholarship, including his misrepresentation of a statement from the historian Roger Anstey. In The Atlantic Slave Trade and British Abolition, 1760-1810, Anstey stated that ‘abolitionists were right to acknowledge Dundas … as the most important cause of the failure of immediate abolition in the Commons in the period up to 1796.’ Mullen, however, elided the words ‘in the Commons’ when citing the historian, and missed Anstey’s other remark that ‘To offer an explanation of the defeat of abolition in the Commons is not, of course, completely to explain the parliamentary failure of abolition.’ For Anstey, these further factors encompassed the arch-conservatism of the Lords, the influence of the French Revolution and the less than effective presentation of the abolition case.

Other historians, such as David Brion Davis, have also pointed out that while Dundas had an influence on the delay, abolition was hardly conceivable at the time due to any number of factors including the anti-abolitionist alliance of the King and royal family, admirals in the navy, commercial West India interests, and landed proprietors.

Some historians have, however, suggested that Henry Dundas mobilised Scottish parliamentarians against a 1796 vote to abolish the slave trade within the year, which failed by 70 votes to 74. Twelve Scottish MPs voted against abolition and one voted for it. According to Mullen, ‘Almost no MPs from Scotland deviated from the committed anti-abolitionist stance of the Scottish manager, Dundas.’

Yet with 45 parliamentary seats in the House of Commons, 31 Scottish MPs did not vote. Dundas was among those who did not cast a vote.

That more Scottish parliamentarians did not vote is surprising in light of the considerable role of Scots in the plantation trades and slave system more widely. As Devine has shown, the impact of slave produced commodities had a more significant impact on Scotland’s Industrial Revolution than England’s.

Why, then, did Henry Dundas fail to mobilise Scottish MPs? Distance from parliament may have been a factor. Part of the answer is also that the vote on abolition was one of conscience on a private bill rather than one run along party lines and loyalties. The extreme volatility of the voting record for and against abolition over the period certainly suggests that Dundas did not in any way have an overwhelming influence over the process and was not the arch controller of Scottish parliamentarians as is suggested.

Many forceful arguments were made by politicians to oppose abolition of the slave trade. They encompassed fears of the ruin of planters, the advantage abolition would give to rival slave trading nations, the supposed benefit of the trade to Africans, and that slavery was not inconsistent with Christianity. Indeed, two-thirds of parliamentary arguments put forward national economic and security issues, reflecting a British society grappling with domestic radical change and the dread of mass risings, radical reform, and social disorder as a result of the French Revolution and associations with slave uprisings. To this we can add the temporary decline of popular enthusiasm for the abolitionist cause. Therefore, although parliament had committed in 1792 to end the British slave trade gradually, politicians made their decisions for or against various ongoing abolition measures within the backdrop of national and international alarms, crises and threats.

David Richardson, a historian who has specialised in research on slavery throughout his long career, has emphasised these factors in his new book, Principles and Agents: The British Slave Trade and its Abolition. He identified several individuals who did not support abolition of the slave trade including those with West India interests, the monarch and his entourage, and some influential Tory and Whig leaders. For Richardson, this collective hostility meant that abolition as a formal government policy was ‘inconceivable before 1806-7’.

Whatever the merits and realities of the political and social landscape when abolition was debated, the evidence suggests that Dundas’s arguments for gradual rather than immediate abolition of the slave trade could not have decisively influenced voting patterns.

Any consideration of Dundas’s role also needs to take account of developments in the immediate run up to abolition including abolitionists’ alliances and their political approach. William Wilberforce, a leading figure in the abolition cause, but one who also attracted personal opprobrium among some, withdrew from debates in 1806 and 1807, letting other figures assume responsibility for taking charge of the relevant measures.

The first achievement was the passage in 1806 of the Foreign Slave Trade Bill which prevented British ships from supplying slaves to foreign colonies. Then, in early 1807, a motion to end the slave trade was passed first in the Lords and then in the Commons so as to circumvent royal influence. The Slave Trade Abolition Bill was finally passed by a vote of 100 to 36 in the Lords and 283 to 16 in the Commons, making it illegal after 1 May 1807 for Britain to continue its long central involvement in the transatlantic slave trade.

That abolition was a key issue during the 1806 general election and MPs had to convey to their constituents their support or opposition for the cause may have prompted many members to back abolition to ensure they were returned to parliament, as abolitionism became popular again throughout the country. The cause of abolition also benefited from the revolution of the enslaved in Saint-Domingue and its independence from the hated enemy France in 1804 as the new state of Haiti.

Historical realities, then, were much more nuanced and complex in the slave trade abolition debates of the 1790s and early 1800s than a focus on the role and significance of one politician.

Instead, a series of domestic and international factors explain the failure to achieve abolition before 1807 including: defence and security anxieties at a time of international war and slave uprising; opposition to any domestic ‘progressive’ reform for fear of giving comfort and encouragement to the menacing forces of contemporary political radicalism; the critical dependence of the UK Treasury for war revenues from the lucrative Caribbean trades; the intransigence of Wilberforce and his overall poor parliamentary management; the occasional complacency of abolitionists; the influence of the West India interest in the parliamentary debates on abolition; effective stalling tactics in the House of Lords; and the unrelenting opposition of King George III, his political coterie and some ministers of the Crown to abolition itself.

As such, the current text on the plaque beside the statue of Henry Dundas can therefore be considered patently absurd, erroneous, and ‘bad history’. Edinburgh City Council have a moral duty to amend or remove it as soon as possible. Otherwise, it faces the grave charge and opprobrium of falsifying history on a public monument.

San Francisco is decaying

During the pandemic, a growing number of people in floridly psychotic states screamed obscenities at invisible enemies, or at my colleagues and me on the streets of San Francisco. One morning, a young man came up to me as I was unlocking our front door and coughed in my unmasked face. Another threatened to assault a colleague. In both cases our mistake appears to have been looking at the men.

Many of the problems stemmed from Covid-19. California’s prisons, jails and homeless shelters were under orders to reduce their occupancy. But none of these problems started with the pandemic. Between 2008 and 2019, about 18,000 companies, including Toyota, Charles Schwab and Hewlett-Packard fled California due to a constellation of problems sometimes summarized as ‘poor business climate.’ California has the highest income tax, highest gasoline tax and highest sales tax in the United States, spends significantly more than other states on homelessness, and yet has worse outcomes.

Though I have been a progressive and Democrat all of my adult life, I found myself asking a question that sounded rather conservative. What were we getting for our high taxes? Why, after 20 years of voting for ballot initiatives promising to address drug addiction, mental illness and homelessness, had all three gotten worse? And why had progressive Democratic elected officials stopped enforcing many laws against certain groups of people, from unhoused people suffering mental illness and drug addiction in San Francisco, Los Angeles and Seattle, to heavily armed and mostly white anarchists in Seattle, Portland and Minneapolis?

No sane psychiatrist believes that enabling and subsidising people with schizophrenia, depression and anxiety disorders to use fentanyl and meth is good medicine. Yet that is what San Francisco, Seattle and Los Angeles are, in effect, doing. What California does with its 100,000 unsheltered residents, most suffering mental illness or drug addiction while living in violent, dangerous and degrading encampments, is mistreatment of the foulest sort. How did we go from the nightmare of mental institutions to the nightmare of homeless encampments?

The question used to be: do you reward people for not committing crimes, or do you punish them when they do? But that’s been superseded by a question from progressives: what if it’s a form of victimisation to try to influence people’s behaviour at all? The governing majority in some of America’s cities seems to believe that the only real public policy problem is how to pay to let people do whatever they want, from turning public parks into open-air drug encampments to using sidewalks as toilets and handing over whole neighbourhoods to people who are heavily armed and purposefully unaccountable.

The crisis of disorder is strongest in progressive West Coast cities. But it is spreading east, like many trends in America do. Progressives have been in charge of San Francisco, Los Angeles and Seattle, as well as California and Washington during most of the decades in which the problems I describe here have grown worse. It was Democrats, not Republicans, who played the primary role in creating the dominant neoliberal model of government contracting to fragmented and often unaccountable nonprofit service providers that have proven financially, structurally and legally incapable of addressing the crisis. On the fundamental policies relating to mental illness, addiction and housing for the homeless, moderate Democrats, conservatives and Republicans have either gone along with the liberal and progressive agenda or been powerless to prevent it since the 1960s.

The crisis of untreated mental illness, addiction and homelessness is growing worse. Between 2013 and 2016, complaints of homeless encampments to San Francisco’s 311 line rose from two per day to 63 per day. Conditions in the city are internationally recognised as inhumane. In 2018, the United Nations’ special rapporteur visited San Francisco and said, ‘There’s a cruelty here that I don’t think I’ve seen, and I’ve done outreach on every continent.’

Many of San Francisco’s homeless live in densely populated, centrally located areas. The most infamous of these is the Tenderloin, a downtown neighbourhood that borders government buildings including City Hall, a major shopping district with several large tourist hotels and many of the city’s concert venues and museums.

Some argue that the homelessness situation in San Francisco isn’t worse than other cities, but studies show that warmer climates and more expensive housing are major factors behind higher rates of homelessness, both sheltered and unsheltered, in San Francisco, Seattle and Los Angeles. In much of California, one can sleep outside for most of the year without freezing. Half of the unsheltered homeless population in the United States is in California and Florida alone, even though the two states are home to just 19 per cent of the population.

High-tech companies like Salesforce, Twitter and Stripe, progressives noted, had attracted thousands of employees who had driven up rents, resulting in tenant evictions. While all big cities struggle with homelessness, the West Coast cities of the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles and Seattle struggle more. The change over the last 15 years has been dramatic. Between 2005 and 2020, the estimated number of homeless people in San Francisco increased from 5,404 to 8,124. The estimated number of unsheltered homeless rose from 2,655 to 5,180. The San Francisco Bay Area as a whole saw sheltered and unsheltered homeless increase by 32 per cent between 2015 and 2020, with the share of unsheltered homeless rising from 65 to 73 per cent. The total more than doubled in Alameda County, which includes Oakland and Berkeley, between 2015 and 2020.

Meanwhile, homelessness declined in the nation as a whole and in other big cities. Homelessness nationwide fell from 763,000 to 568,000 between 2005 and 2020. In the same 15-year period, the homeless populations of Chicago, Greater Miami and Greater Atlanta declined 19 per cent, 32 per cent and 43 per cent respectively. While it is true that New York City saw an increase of 62 per cent in its homeless population between 2005 and 2020, over 99 per cent of New York’s homeless have access to shelter. In San Francisco, just 43 per cent do.

San Francisco has a much higher share of unsheltered homeless who are ‘chronically homeless’ than other cities. The US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) defines the chronically homeless as those who have been homeless for a year, had four episodes of homelessness totalling 12 months in the last three years, or those who are too disabled to work. Of the roughly 5,200 unsheltered homeless people in San Francisco, 37 per cent in 2020 were chronically homeless.

While the homeless are poor, few poor people live on the street. Nearly 90,000 people in San Francisco live in poverty but just over 8,000 are homeless. The vast majority of people, including the very poor people who are priced out of San Francisco’s expensive rental markets, move out of the city or move in with friends or family. Vanishingly few decide to pitch a tent on the filthiest sidewalks in America.

The answer must be redevelopment. But this comes at a price. It can cause changes in the demographics of a neighbourhood. Critics complain of too many tourists, too few arts venues and rising rents for those units that do not receive subsidies. But the price of not redeveloping is much higher: the destruction of human dignity and civil society.

Redevelopment makes housing more abundant and can reduce the concentration of poverty. It grows the tax base and generates revenue to improve schools and transportation. That’s what happened in New York City when the open-air drug markets in the Alphabet City area of the Lower East Side were closed and the area redeveloped.

Redevelopment is a chance to make the Tenderloin, the Blade and Skid Row walkable, liveable and beautiful. I am surprised to find little opposition to redevelopment, and even some enthusiasm. Given California’s stagnation, we cannot allow our response to the untreated addiction and mental illness crisis to depend upon significantly expanding the overall housing stock. Human dignity, and the sanctity of our cities, must come before the political agendas of NIMBYs, YIMBYs and everyone else in between.

At the same time, the Tenderloin, Skid Row and the Blade cannot be the only sites of new housing development. Attempting to make them that would be unfair and impractical. If California ever chooses to return to population growth, while reducing the impact of historic injustices, the state will need to build a lot more housing, from apartments and condos downtown to fourplexes and adjacent dwelling units in the suburbs.

In exchange for more apartments downtown, Californians could agree to more suburbs on former farmlands. YIMBYs sometimes misdescribe how cities add housing. Cities around the world, from Tokyo to Atlanta, become more dense as they grow outward. Some pro-density advocates point to Tokyo as a city that grew its population without taking up more land, but Tokyo’s area increased 54 per cent from 1990 to 2010. Its rate of expansion doubled during this time, and it became less dense overall. Housing in suburbs is far cheaper to build than in the cities, which is how Tokyo and Atlanta have been able to keep overall housing prices comparatively low.

Those who move to the Bay Area, and pay dearly to remain, do so in part to enjoy California’s spectacular natural environments. These public areas should remain off-limits to any kind of development. But allowing for suburbanisation of California’s ranches and farmlands would still allow for strong protections of California’s scenic natural areas like Yosemite, the redwoods and the oak woodlands and green spaces near cities.

The obvious way to do so is by rescinding the regressive tax breaks California and other states give to uneconomic farms and ranches. Over the last several decades, the amount of California’s land that was converted from farming to housing has declined. In 2009, five times more of California’s land was used for pasture (17 per cent) and farming (8 per cent) than for cities and suburbs. People should be free to use their land for uneconomic purposes, but they should not be subsidised by taxpayers, particularly when the land would have far higher value as housing.

Whether or not housing can be significantly expanded in California, we should redevelop neighbourhoods that have been taken over by open-air drug scenes for strictly humanitarian and public order reasons. Americans not suffering from serious mental illness should have a right to shelter, though not to a studio apartment, much less one in one of the world’s most expensive downtown real-estate markets. Shelters should be safe, clean and humane. But they also must be low-cost, basic and not so nice as to serve as an incentive to homelessness. And better housing should be earned, not given away unconditionally.

Over the last two years we have seen a disturbing rise in politically motivated disorder. In each case, elected officials not only failed to respond swiftly and decisively; they contributed to the undermining of law and order. In every case I felt an anxiety I had never felt before: the fear of losing my country. I began to genuinely worry that America could become like one of the undemocratic and unfree nations I have visited over the decades. Disorder and the loss of freedom go hand in hand. Political leaders who fail to maintain order are often replaced by leaders who sacrifice freedom.

Many of the people who enjoy some of the highest levels of prosperity and freedom in human history are also the least grateful, and least loyal, to the civilisation that made it possible. The progressive obsession with changing the names of schools and tearing down statues of people allegedly guilty of genocide in the past comes at a time when our greatest global rival is actually guilty of committing one in the present. Today, America is so divided that some progressives are openly proposing that America split apart. This suggestion raises a question similar to the one the psychologist Viktor Frankl demanded of his depressed clients: Why doesn’t America commit suicide? What should America live for?

The traditional answer is freedom, but Americans are deeply divided over its meaning. Today, that starts with valuing freedom as a state of affiliation, not disaffiliation, and of responsibility to, not freedom from, one another as fellow Americans. We must return to a view of freedom that is universal, and not just for people designated as victims. We must affirm equal justice under the law, and equal enforcement of the law.

The American frontier closed over a century ago, and Western values, Californian ones especially, increasingly define the whole of the United States. But we in the West are not living up to our role as leaders, or to our duty to one another as fellow humans and citizens. It is time for us to grow up. That should start in California, the state that most embodies the American frontier spirit and our love of freedom, and in San Francisco, the city that most embodies our ingenuity. It is here, perhaps in the bay that connects the city to America, that we should complete the American project and build what Frankl proposed: a Statue of Responsibility.

Will Trudeau’s clampdown on the Freedom Convoy backfire?

Canada has long been viewed as a peaceful, welcoming country. Like most western democracies, it has witnessed some difficult historical moments: divisive election campaigns, Quebec separatism, and policy debates on free trade, capital punishment, gay marriage and decriminalising marijuana. While these issues led to periods of tension, cooler heads have usually prevailed.

The Freedom Convoy, however, which has seen hundreds of truckers converge on Ottawa and the blockade of cross-border trade with the US, has been a moment like no other in modern Canada.

The Freedom Convoy’s important message of more individual freedom and less government restrictions and lockdown measures during Covid-19 resonated with many Canadians. Conversely, the potential economic ramifications from traffic logjams, blockades and reduced amounts of cross-border trade has started to divide family, friends and neighbours. People want the protest to have a peaceful resolution, and not lead to further frustration, anger – or worse.

How the Freedom Convoy got to this point is an intriguing story on its own.

The PM’s strategy was a failure and only served to increase interest and sympathy for the cause he opposed

On January 15, Canada’s minority Liberal government announced a Covid-19 vaccine mandate for cross-border truckers. It was a significant policy shift. Truck drivers and other essential workers had been exempt from the two-week quarantine rule for unvaccinated travellers crossing the Canada-US border. Meanwhile, the Canadian Trucking Alliance had estimated that 85 per cent of Canada’s 120,000 truckers were vaccinated. If the vast majority of men and women who drove the big rigs were complying with the rules, why were they being targeted?

While these matters could have been managed without a restrictive government mandate, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau motored ahead. He knew that most Canadians were fully vaccinated – 78.69 per cent as of Feb 4, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada. Meanwhile, a January 19 poll by Maru Public Opinion found that 66 per cent of respondents favoured ‘mandatory vaccinations for everyone aged 5+.’

Trudeau, a left-leaning Liberal whose political antenna has regularly been on the fritz since taking power in 2015, misread the room once more. Two years of restrictions and lockdown measures had reached a tipping point in the Great White North. The bizarre decision to target truckers, who serve such a vital role in transporting goods and services, was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

In response the Freedom Convoy was organised to protest mandatory Covid-19 vaccines for the trucking industry. Participants came from across Canada, linking together on the nationwide Trans-Canada Highway. A GoFundMe campaign that started off with the ambitious goal of raising $7 million (CDN) surpassed $10 million, although that money has been frozen until organisers reveal where it will be used and spent. Although quite a few truckers participated in the protest, the majority were Canadians who drove their cars to the nation’s capital in Ottawa, in support of the cause of freedom.

Trudeau pushed back by depicting the protesters as a ‘fringe minority’ with ‘unacceptable views.’ This harkened back to Hillary Clinton’s description of half of Donald Trump’s supporters as being a ‘basket of deplorables’ during the 2016 US presidential election. The PM’s strategy, much like Clinton’s, was a failure and only served to increase interest and sympathy for the cause he opposed.

Meanwhile, Liberals pointed to some less-than-savoury characters who latched on to the Freedom Convoy. A Nazi swastika and Confederate flag were seen in the crowd, while a statue of a national hero, Terry Fox, along with the National War Monument and Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, were desecrated. None of these things were defensible. Alas, that’s what often happens at rallies, marches and protests – be they left-wing, right-wing or no wing. No one has a monopoly on the higher moral ground.

There’s also been the unmistakable fact the Freedom Convoy has largely been a peaceful gathering. Protesters come from all parts of Canada, and represent all walks of life. They’re tired of restrictions, mandates and lockdowns. They’ve suffered economically and emotionally. They want to regain control of their lives, and want things to return to normal (or whatever the ‘new normal’ entails).

This is all perfectly reasonable, and difficult to achieve in a protest that won’t end.

Some protesters have said they won’t leave Ottawa until the Liberals either meet their demands or resign completely, which obviously won’t happen. Truck horns have been banned for ten days in this city, which led to an unfortunate (and avoidable) incident with police arresting and handcuffing a 78-year-old retired janitor who defied this rule. Similar protests have occurred in cities like Toronto, and Coutts. The Ambassador Bridge in Windsor, a crucial international border crossing between Canada and the US, is in the midst of a blockade that’s stalled cross-border trade. Ontario Premier Doug Ford, a Conservative, declared a state of emergency on Friday to help bring the blockades and protests to an end. On Saturday, police officers moved to break up the Ambassador Bridge protest.

Where do things go from here? The next few days could end up being some of the most important in Canadian history. Let’s hope that cooler heads prevail once more.

How Britain’s fracking industry was regulated into irrelevance

This week the fracking company Cuadrilla announced that it was permanently closing its two shale mines in Lancashire, after the Oil and Gas Authority (OGA) declared that shale gas companies must seal up the wells they had drilled and return the land to nature.

It is, on the face of it, a very strange step to take at this time. The wells have not been producing any gas for some years, of course, ever since environmentalists launched their scare campaign against the industry. It was a campaign that was astonishing in its brazenness. Tiny earth tremors recorded near the wells, of a scale that is entirely normal in, say, the mining industry or in geothermal energy developments were rebranded by activists ‘earthquakes’. The chemicals used – all licensed as entirely safe by the Environment Agency – were declared to be dangerous poisons. In one particularly egregious case, householders were given leaflets which claimed that the gas companies were going to use industrial quantities of a known carcinogen called ‘silicon dioxide’. That’s sand, in common parlance.

And just as they have always done, environmental correspondents across the mainstream media relayed it all to a mostly credulous public, with not a note of doubt raised.

The aim of the campaigners and their media allies was to destroy the industry before it took off, or at least to have it regulated into irrelevance. At first, the government held its ground, but with the media in full chorus that didn’t last for very long. After drilling operations caused a pair of microtremors (of a size somewhat smaller than a lorry rumbling past your window) the scaremongering reached a new intensity. Stories were circulated to the media that homes had been damaged. These claims were later shown to be baseless, but by then the government had had enough, and their resistance crumbled. New rules were put in place that made operators stop work if they caused even a tiny earth tremor. The so-called ‘red light’ level was set so low – far below anything detectable – it was said that if you wanted a long weekend, all you had to do was drop a spanner on the drilling pad on Thursday evening.

The government was making it abundantly clear that they had decided they could do without onshore gas (or at least the political flak that came with it) a message that was reinforced by the fact that no other industry that caused earth tremors had to operate under the same strictures.

Soon afterwards, an outright moratorium followed, and the wells have sat idle ever since. Three years on, however, we are in a very different political landscape. Covid was bad enough, but we are now in danger of being overwhelmed by an energy price crisis too. Unusually for the energy and climate arena, everyone is in agreement: the proximal cause of the crisis is the price of gas, which has surged as the world recovers from the pandemic. Heating bills have shot up in response, and because the market price for electricity is set by gas turbines, there has been a knock-on effect on power prices.

If high gas prices are the problem, then reasonable people might conclude that the solution would involve delivering lower prices, which in turn would mean increasing the supply. Of course environmentalists will say that we should instead build more windfarms and install more heat pumps, but these projects would take several decades to deliver, so they are of little help in the near future. And even in the rather longer term, they would still not help, because market prices are set by gas turbines (the marginal generator, in the economic jargon); that’s why they are currently so high.

That means that the only way out of the crisis in the next few years is to drive down the cost of gas. An increase in the domestic supply would help, because it would enable us to replace some of our more expensive imports, and in particular liquefied natural gas.

This being the case, how can we explain the decision to seal the wells up? In fact, it makes sense if you take a look at the OGA’s remit. In this extraordinary document, you will find no mention of any duty to ensure that operators aren’t cutting corners. There is nothing about making sure that they deliver for consumers, nor even anything about national energy security (another issue of pressing urgency, given Mr Putin’s machinations). Instead, the role that government has given it revolves entirely around delivering Net Zero. Put bluntly, the OGA is more about closing the industry down than regulating it.

When the price cap on domestic energy bills is lifted in a few weeks’ time, there is likely to be a great deal of anger. If people learn that the government’s political cowardice has been making things worse, a major political backlash is on the cards.

The fading legacy of Deng Xiaoping

After Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, it was clear to pragmatists in the Chinese Communist Party, led by Deng Xiaoping, that Maoism had not worked.

By the late 1970s, food production had failed to keep up with population growth and nine out of ten Chinese were living on less than $2 a day. But the Party didn’t want to admit the inviability of communism, its raison d’etre. Instead, it dubbed the ensuing decades of privatisation, foreign investments and lifting of price controls ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’.

So the country remained nominally communist, even though state-owned enterprises were liquidated en masse and the private sector made up the bulk of Chinese GDP by 2005. For hundreds of millions of ordinary Chinese, like my family, reform and opening were keenly welcomed. My uncle was the first in the family to go to university; my mother found work in an international company in the city. When I came along, my childhood was not marred by hunger.

But the CCP has moved on from Deng. These days, instead of ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’, the Party talks about ‘the new era of socialism with Chinese characteristics with Xi Jinping as core’. With the abolition of term limits and an increasingly tight grip on China’s civil society, government, military and so on, Xi Jinping had already shown himself to be an ambitious Communist leader more akin to Mao and Deng than their relatively bland successors (Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao). But this year, as Xi reaches the end of his first decade in power, this is no longer enough. Xi wants to be second only to Mao, with Deng’s legacy a necessary casualty.

Xi wants to be second only to Mao, with Deng’s legacy a necessary casualty

Nowhere was this more clear than in the rare Resolution on Party History published at the Sixth Plenum last November. To read the document, one would have thought that Deng was no more important in Chinese history than presidents Jiang or Hu. A nod was given to the Deng’s role in initiating reform and opening, but by and large the document commemorated the Mao years (while acknowledging the ‘mistakes’ of the Cultural Revolution) and set out the CCP’s ambitions for the Xi era. Xi’s name was mentioned 22 times, Mao’s 18, and Deng’s only six.

Those ambitions are a more assertive, centralised and socialist China, quite different to what Deng envisaged. In a country that still reveres the former paramount leader and his policies, Xi knows that he can only push through his own agenda by subtly forging a personal legacy that is greater than Deng’s. The rhetoric of the November Resolution bolsters the very real changes directed from Zhongnanhai, the guarded Beijing complex where China’s top leaders reside.

This year, expect to hear more about ‘common prosperity’. Deng was unabashed about unabated economic growth, encouraging ‘some regions, some people to get rich first’, Xi put a stop to that. These days, the CCP talks about tackling ‘excessive wealth’ (never quite defining what that means). Billionaires like Jack Ma have had their knuckles rapped through tightening regulation on debt and monopolies (in Ma’s case, a last-minute policy change meant he had to pull the listing of his fintech company, Ant Financial, valued at $310 billion).

Chinese companies now fall over backwards to pay penance for being successful – Ma’s e-commerce firm Alibaba has pledged $15.5 billion to the ‘common prosperity’ cause, and Tencent, the company behind WeChat and the game League of Legends, has pledged a similar amount of money to poverty alleviation. ‘Tencent is just an ordinary company in the greater scheme of the country’s development… [We will be] good helpers’, Tencent’s Pony Ma said recently.

There are also efforts to end the borrowing and infrastructure spending that fuelled China’s early growth. Real estate is the biggest offender, which is why the giant developer Evergrande and it’s founder Xu Jiayin have been targeted. (Former businessman Desmond Shum’s memoir Red Roulette contains a fascinating vignette of when, in 2011, Shum talked Xu out of buying a luxury yacht off the Côte d’Azur because ‘for $100 million you’d expect more elegance, dangling chandeliers’.)

Amid rumours of a property tax coming this year and President Xi saying things like ‘houses are for living in, not for speculation’, the Chinese property market has tanked. The value of home sales fell by 16 per cent in November and S&P estimates that a third of China’s listed developers could face liquidity problems this year.

This latest turn away from Deng comes on top of Xi’s already different approach to diplomacy and politics. When dealing with foreign nations, Deng’s maxim was taoguang yanghui – keeping a low profile and focusing on domestic growth (which has controversially been translated as the ominous ‘hiding your strength and biding your time’). It served the country well in the face of international backlash over the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown – so much so that Hong Kong would still be returned to China by 1997 and the country would join the WTO by 2001. Xi’s wolf warrior diplomacy, enshrined in Xi Jinping Thought, is the polar opposite of that approach.

In politics, the abolition of term limits and the de facto ending of collective leadership within the Politburo Standing Committee overturned two constitutional reforms Deng introduced. Presumably, having personally suffered and seen the country suffer under Mao’s unchecked power, Deng thought these checks imperative. It was also Deng who proposed the ‘one country two systems’ principle to Margaret Thatcher, vital for the peaceful return of Hong Kong. That arrangement is now dead under Hong Kong’s National Security Law, with real implications for any peaceful reunification of Taiwan. To the west of the country, in dealing with the ethnic minorities of Tibet and Xinjiang, Deng favoured pluralism, recognising their differences and encouraging cross-border trade for the sake of growth. Nobody could say that is what’s happening in Xinjiang today.

Yet turning away from Deng is not about Xi’s vanity (at least, not just). Today’s China has new and serious problems. For one, rapid economic growth came with rampant corruption and growing inequality. There is a housing crisis for younger generations, despite the fact that there are enough empty flats in the country to house the entirety of the British population, as the Financial Times worked out last year. Shum vividly documents the extraordinary extravagance of those made super rich by reform and opening (he barely blinked at spending more than $100,000 on wine at a meal). My family didn’t make that kind of breakthrough, but we knew that our lives were still much better than others in the countryside and to the west of the country, where the wealth had yet to trickle through.

Xi has been explicit that economic inequality creates social problems. He points to America’s culture wars as evidence. ‘[In] some countries, the divide between poor and rich and the collapse of the middle cause divisions in society, extremism in politics and populism runs wild – this is a very profound lesson!’ He fears that one can already start to see this in the millennial movement to ‘lie flat’, where young people are protesting the pressures of modern life through voluntary unemployment and singledom.

The strength of modern China also gives Xi options that Deng simply didn’t have. How much of his ‘bide and hide’ was a strategy of necessity when the Chinese economy was a mere 6 per cent of American’s GDP, and the People’s Liberation Army mainly equipped with Soviet cast-offs? Xi has calculated – probably correctly – that China can now throw its heft around to achieve its territorial and political goals. It can elbow others out of the South and East China seas, boycott Australian coal and wine when Canberra misbehaves, fly its warplanes over Taiwan’s self-declared airspace. It no longer needs to hide.

It’s also not simply a case of Deng the good liberaliser vs Xi the hardline Marxist revanchist.

If he were alive now, Deng may well agree with some of Xi’s approach. Deng was no softie – the tanks would never have moved into Tiananmen Square without his say so. In the process of quelling the student protests, Deng also sold out his liberal-minded protégé, the then-General Secretary Zhao Ziyang, who wanted to negotiate. Hundreds – some say thousands – of young people died on June 4 1989, and Zhao spent the rest of his life in house arrest. Zhao’s memoir, smuggled out of China and published posthumously, reflected on his erstwhile mentor: ‘Deng had always stood out among the party elders as the one who emphasised the means of dictatorship. He often reminded people about its usefulness’. For Deng as for Xi, the Party always came first.

Deng the diplomat could be charming, as Mrs Thatcher found. He’d think little of the childish jibes that China’s wolf warriors now tweet. And on the issue of term limits, his constitutional reforms were only in place for 35 years (facilitating three peaceful exchanges of power) before being overturned. Deng, who was sent to a tractor factory by Mao during the Cultural Revolution, put limits in for a reason.

Trying to divine what’s happening behind the scenes in Zhongnanhai will forever be akin to watching shadows on the cave wall. There are signs of a Dengist fightback. In September, Professor Zhang Weiyin, an economist at Peking University, warned against the common prosperity agenda: ‘If we lose our conviction in the market, bring in more and more government intervention, China can only walk towards common poverty’. Just before Christmas, an intriguing article was published in the People’s Daily. Authored by Qu Qingshan, an esteemed party historian, the article headlined ‘Reform and Opening was an awakening for the Party’ and made no mention of Xi Jinping at all. Instead, it piled praise on Deng Xiaoping and lauded the Party’s efforts in allowing the people to make the most of reform and opening. This comes on top of Deng’s own son’s caution to the Chinese leadership in 2018. ‘Keep a sober mind and know our own place’, Deng Pufang said in what was read by some as a subtle denunciation of the emerging wolf-warriorism. He made the comments to China’s Disabled Persons’ Federation (he had been paralysed in the Cultural Revolution), but the speech never made it onto the website subsequently.

Perhaps Deng Jr and these academics represent a wider movement in the CCP that opposes Xi’s direction, or (more likely) they are just a small band of old-fashioned liberals who are out of step with a Party that largely coheres around the current leader. There’s unlikely to be any real opposition to Xi Jinping as he begins his third term in this autumn’s National Party Congress. Deng Xiaoping would have wanted Xi to appoint a successor, but what Deng wants matters less and less each day in today’s China.

New Yorker: Cressida Dick handled de Menezes killing with ‘dignity and grace’

For some time now the New York Times has been a pioneer in the field of dodgy reporting on Britain. From declaring that Brits live on porridge and boiled mutton to suggesting that we love to cavort in swamps, the US paper of record has managed to paint an increasingly strange picture of life in this country. But could the NYT now be facing stiff completion from the New Yorker in the British fantasy genre?

This weekend, the magazine published a strange defence of Cressida Dick, after she was forced to resign as commissioner of the Metropolitan Police by Sadiq Khan.

The New Yorker piece, headlined ‘The Misogyny That Led to the Fall of London’s Police Commissioner’ argues that the police chief’s downfall came after she was ‘overwhelmed’ by the misogyny of the men she led – as opposed to the catalogue of errors that defined her career. This line of argument is rather undermined by Cressida Dick’s own tone-deaf and embarrassing responses to recent police scandals which saw the Met, for example, advise women to flag down a bus if they were approached by a lone male police officer following the arrest of Wayne Couzens.

But Steerpike was more concerned about the US magazine’s characterisation of the killing of Jean Charles de Menezes, who was shot dead by Metropolitan police officers on the tube in 2005, after they mistook him for a suicide bomber.

The New Yorker writes:

‘In 2005, Dick was in charge of the counterterrorism team that killed Jean Charles de Menezes, a Brazilian man, on the Tube, after mistaking him for a suicide bomber. Dick always handled that momentous error with dignity and grace.’

To describe de Menezes’s killing – which saw an innocent man shot seven times in the head by police officers – as being handled with ‘dignity and grace’ is stretching the truth to say the least. Cressida Dick was Gold Commander in charge of the bungled operation, which was later found to have committed catastrophic errors, although Dick was cleared of personal responsibility. Still, Dick didn’t quite seem to grasp the gravity of the Met’s errors when she told an inquiry in 2008 that ‘If you ask me whether I think anybody did anything wrong or unreasonable on the operation, I don’t think they did.’