-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

The strange revival of France’s Jean-Luc Mélenchon

Jean-Luc Mélenchon is on the march once more, rising up the polls and laying bare the ineptitude of the Socialist party. While their candidate in the presidential election, Anne Hidalgo, is stuck on two points, Mélenchon is on 17, behind only Marine Le Pen, on 23, and Emmanuel Macron on 26. It was a similar story in the 2017 election when the veteran left-winger received 19.6 per cent of votes in the first round, while the Socialist party’s Benoît Hamon mustered a risible 6 per cent.

There’s a contradiction to Mélenchon in that while at 70 he is the oldest candidate in the race, he is the most technical savvy in getting his message across. On Tuesday evening he repeated his 2017 hologram trick, addressing an audience live at the Grand Palais in Lille while his 3D image was beamed onto stages in 11 towns or cities across the country, from Le Havre in the north to Nice in the south. There was also a mini hologram initiative launched on social media, using Instagram and Twitter to urge voters to cast their ballot on Sunday.

‘We are aiming for a mesh across the territory,’ explained Bastien Lachaud, the organiser of the event. ‘Jean-Luc Mélenchon or one of his holograms will be less than 250 kilometres from every French person.’

The 2022 election is a stark choice between two vastly contrasting visions of France

For some French, being 250km from Mélenchon – even if it is a hologram – is uncomfortably close. They hold that his agenda of social justice and economic redistribution, championed by Francois Mitterrand’s government in the 1980s, is to blame for the decline the country has experienced this century. It’s no surprise that for voters able to remember most clearly the difficulties of that decade, the over-70s, Macron is the most popular candidate, whereas Mélenchon scores best with the 18 to 24 demographic.

Mélenchon joined the Socialist party in 1976 and was a ‘Mitterrandist’ in the 1980s. He left the party in 2008 for a combination of reasons, Europe being an important element. In 2005 he had led the left’s ‘Non’ campaign when the new European Constitution was put to a vote in a referendum. His side won but the political elite ignored the result and complicit in the chicanery were some influential figures on the left, including François Hollande and Ségolène Royal. Mélenchon remains hostile to Brussels and was one of the few French political figures to give Brexit his unequivocal support, using the Leave vote to call for France to hold its own referendum.

Disillusioned with the Socialist hierarchy over their attitude towards Europe, Mélenchon quit the party in 2008 and formed the Left party before founding in 2016 La France Insoumise. He left last October to concentrate on his presidential campaign but it’s noticeable that his election pamphlets don’t mention the party; that may be because in the eyes of some more traditional and older left-wingers, FI is associated with the intolerance of identity politics. Mélenchon himself has come into conflict with this dogma. Two years ago, as the Black Lives Matter movement swept the West, Mélenchon rubbished the notion of ‘white privilege’.

Like Le Pen, Mélenchon is a voice for the disenchanted working class and that explains why the pair are polling well. On the two-sided pamphlet I was handed this week Mélenchon’s manifesto was condensed into six bullet points, among which were a) increasing the minimum wage, b) lowering the cost of petrol and food and c) re-establishing the age of retirement at 60 from its current 62. Macron intends to raise it to 65.

Easier said than done, but the presidential election is much less about the minutiae of policy (which is the focus of the parliamentary elections in June) and more about the personality of the person running to be president. Macron is good on detail but his character repels a great many people. Mélenchon, on the other hand, might be stuck in the 20th century economically but, like Pen, he appeals to provincial France, where deindustrialisation has hit hardest.

The 2022 election is a stark choice between two vastly contrasting visions of France: the progressive globalism of Macron and his ‘anywheres’, against the protectionism of Le Pen and Mélenchon’s ‘somewheres’.

Mélenchon, who used the recent revelations about the billions spent by Macron’s government on private consulting companies to rail against capitalist cronyism, is urging the left to unite. Don’t vote for Hidalgo, the Green’s Yannick Jadot or Fabien Roussel of the Communists because it will be wasted. Vote for me. It seems to working and on Friday Christiane Taubira, the Justice Minister in Hollande’s government, called on the left to support Mélenchon.

In 2017 Mélenchon earned the opprobrium of the political centre when he refused to endorse Macron in his second round duel with Le Pen. He was asked in a radio interview this week if would remain neutral in a repeat of the clash. Mélenchon scoffed and replied: ‘It’s not going to happen’. He is confident he’ll win through to the second round, and he also thinks he knows who he’ll be facing: Marine Le Pen.

Is Rishi just too rich for politics?

The obvious and perhaps only way out of this mess for Rishi Sunak was for his wife to pay double taxation: that is to say, to be taxed in India for any income on her 0.9 per cent stake in Infosys, the $100 billion company set up by her dad, and then taxed in the UK too. She doesn’t make this point in her statement. To talk about double taxation would sound like complaining – and already the idea of the Sunaks being irritated by questions about their tax affairs is being used against them.

The Chancellor might be privately annoyed, arguing this double tax has never been required of anyone before. Is this to be the new test for the spouse of anyone in public life? But, as I say in my Daily Telegraph column, there has never been a Westminster Wag like Akshata Murthy. A Chancellor whose family wealth exceeds that of the Queen is a scenario that was always going to raise issues. So might her decision to pay full UK tax put an end to this? Or is the real problem that Rishi is just too rich for politics?

Britain tends to be no country for reverse snobbery, which is why Labour’s class-war attacks always misfire. Wealth, here, tends to cause more interest than resentment and no one really minded that Sunak, a self-made multi-millionaire in his own right, would move into (and, from his own pocket, redecorate) 11 Downing Street with a wife who was worth over £500 million. No one criticised Sunak for being rich: at most “Dishy Rishi” was teased for being suave and having expensive tastes. What mattered was his economic handling of the pandemic, his creation of a furlough scheme that will (for good or ill) define his time in office and whether he could navigate Britain through the economic hazards that were certain to follow the pandemic.

Sunak should try to get ahead of the next round of investigations by making sure there are no more secrets left to unearth

The navigation grew tricky. After going along with the PM’s spending requests, he saw it as his mission to wean the Tories off debt-financed spending – so he insisted that National Insurance rises pay for No. 10’s care home plan. So tax rises went ahead, inflation went up and his approval rating down. Then came the questions about his wife’s financial affairs: did her company still invest in Russia? His response – rather snappy, saying she is not a public figure and doesn’t have to answer such questions – seemed to expose a vulnerability. Which, naturally, his opponents kept pummelling away at. Her non-dom status, when leaked, was incendiary.

The problem in politics is not wealth. It’s that the super-wealthy tend to be super-careful about tax exposure, using methods which – while legal and above board – sound dodgy. This rule is fairly well established. Every so often we see a data dump from the Cayman Islands or some such where people conducting perfectly legal global business are named and shamed as tax dodgers. In fact, they are tax avoiders, not evaders – but the difference doesn’t matter in Westminster. The words ‘non-dom’ is toxic, as are the words ‘offshore’ and ‘tax haven’.

This could be Sunak’s vulnerability now. Those with assets split globally often want to pay tax by jurisdiction: his wife could pay Indian tax in India, American tax on her Californian pad and UK tax on UK earnings. There are complicating factors that mean she can’t wrap it all under one jurisdiction: Indian capital movement laws make it hard to remove taxable assets, for example. When global financial holdings are managed, it’s often done in a tax haven: not to avoid tax, but to avoid double taxation. Or to avoid taxes on a transaction when the proceeds may later be reinvested. But if you touch a tax haven, you can be portrayed as being dodgy.

Sunak could have got ahead of this row by declaring his wife’s non-dom status as soon as he entered government. MPs are banned from being non-doms so there are obvious issues if their spouse is a non-dom. The fact that this was kept secret (the Cabinet Office was told but the PM is letting it be known he was not) speaks to the problems it was going to cause. As you read this there will be at least three dozen investigative journalists going through accounts registered in far-flung islands to try to document the Sunak tax archipelago and find any embarrassing details. So Sunak should make sure he has given a full and final disclosure; that there are no more secrets left to unearth.

To many of his critics, this is not about wealth or even tax but unmasking Sunak: rather than a ‘British dream’ success story, he’s actually a member of the global elite playing at politics while it amuses him but ready to up sticks and return to California at any moment. And that the non-dom scandal has simply exposed his gameplan: his wife is now quite open about the fact that she doesn’t regard herself as a permanent British resident (or domicile) so surely the same must apply to him. This is perhaps the most potent of the accusations against him: not that he’s rich or a tax-dodger, but that his family is just passing through Britain. And that this explains why he seems to have kept his options open with that US Green Card.

Again, I recognise these attacks. My Swedish wife would never renounce her Swedish citizenship. This isn’t because she doesn’t want to settle here but (for the sake of argument) if her family became ill and she wanted to go back and look after them, she’d like that option. If she later on decided that Britain wasn’t working out for her, I’d move back to Sweden with her – just as she came to Britain for me. That’s the case in a lot of mixed-nationality marriages. I don’t think that makes me any less patriotic (to Scotland and Britain) but I’m mindful that someone can attack me as a kale-munching Europhile. And if they do then: guilty as charged.

Fundamentally, Sunak has a good story: he made his own fortune fairly through his talent and entered politics to give something back – when he could have made far more money had he stayed in the private sector. (The same is true for Sajid Javid and Nadhim Zahawi.) As for Akshata Murthy, she is precisely the kind of person we want in Britain having already invested in UK companies and donated to UK charities. The Sunaks showcase Global Britain very well and I’d argue that, in general, the country needs more couples like them.

If Sunak has been straight over the situation and there’s not some fresh scandal about to break then he should get through this. if he hasn’t, we should find out soon enough.

The fightback against Sturgeon’s secret state

Few of Nicola Sturgeon’s promises have aged worse than her pledge to be ‘the most accessible First Minister ever’. The SNP launched its council elections campaign yesterday but refused to invite any print journalists: an effective press blackout designed to shield the party’s leader from questions on policy. Some newspapers declined to cover the event; others denounced it as a sham.

As Conor Matchett of the Scotsman points out, the move is in keeping with the party’s long-term media strategy: a broad distrust of the print press and a belief that independence and SNP support will be won online and on TV and not through legacy media. Newspaper sales have halved since the SNP came to power: why risk an awkward stand-off at the launch going viral when you can release hand-picked images instead?

Few governments welcome interrogation: in a nationalist party like the SNP, questions are often conflated as criticism of the state itself. Michael Simmons and I have written about this in this week’s Spectator, explaining how the SNP’s preference for secrecy leads to worse outcomes. We chose to focus on the Ferguson shipyard saga but there are other episodes we could have used like the bailouts of Bifab and Prestwick airport or the botched Rangers FC prosecutions.

The record makes for bleak reading. But there are now signs of a belated fightback. The Alex Salmond trial triggered a civil war that laid bare much of the SNP’s internal workings and Holyrood’s institutional shortcomings. Sturgeon’s opponents in Edinburgh and in London ought to study these closely and seek to strengthen the checks and balances on her power.

The Scottish Conservatives, for instance, have woken up to the SNP’s centralising tendencies. Sturgeon and others like to present independence as an emancipatory project while preferring to hoard power in the Central Belt. Tories north of the border have therefore begun championing an alternative vision of devolution that gives powers back from Edinburgh to local councils. Westminster’s vibrant eco-system of think tanks and pressure groups is also largely absent in Holyrood; former Tory MP Luke Graham will be launching the British Civic Institute later this month to address this.

In London, there are plans for the forthcoming Queens’ Speech to include measures for UK-wide data collection hubs, allowing proper metrics to be kept of public sector services across Britain. This will help curtail the SNP’s tactic of ‘data divergence’ – pulling Scotland out of international league tables to hide poorly performing schools and hospitals.

Such initiatives are unlikely to topple the SNP from their seemingly-unassailable status as the natural party of Scottish government. But what they might achieve is a more accountable form of Scottish government: one less prone to waste, mismanagement and unnecessary secrecy.

The Russian army is running out of options

So much had been written about the Russian armed forces’ modernisation and improvement over the last decade that that it was widely believed that the Russians possessed one of the largest and most powerful armies in the world until a few weeks ago. The army might not be on par with the US or China, but it was certainly capable of conquering a military minnow like Ukraine – or so the logic went.

The six weeks of war in Ukraine – which have seen Russian forces fail to take Kyiv and fall back elsewhere – has dented the army’s reputation. And now it seems that the Russian military may be running out of options in the rest of the country too.

There is growing speculation that following the Battle of Kyiv the Russians are now going to consolidate their forces in the east and south to restart major offensives. This could include surrounding Ukrainian forces in the Donbas and or even, as one general hypothesised on CNN, a large thrust to seize the strategically located Ukrainian city of Dnipro.

Rushing Russian soldiers back into the war would be a sign of the panic engulfing Putin’s leadership and represent a huge risk for the Kremlin

The problem is that this would rely on a Russian army that does not seem to exist. Any force able to launch major operations in the east to advance rapidly through Ukrainian positions and seize major Ukrainian cities would need to be capable of quickly rebuilding and resupplying defeated units, learning a great deal from its earlier mistakes and mastering complex operations. The Russian army has struggled mightily with all of these things so far.

Instead of being able to successfully launch major offensives in the east and the south, the Russian army will probably do what it has done since the campaign started: struggle to maintain its force levels, struggle with logistics, and make smaller incremental gains in some areas while being pushed back in others. This is first and foremost because the Russian army that went into Ukraine was too small, and the rest of the Russian army does not possess the kind of troops that the leadership trusts to actually make a difference.

Far from being particularly large, the Russian army is actually only a medium sized force with a relatively modest element that is considered combat effective. Russia invaded Ukraine with somewhere between 190,000 and 200,000 soldiers, and that force was considered to contain about 75 per cent of all the decent combat effective units in the army.

So far these 75 per cent of the best troops in the Russian army have struggled. They were defeated around Kyiv and forced into a hasty retreat after suffering high casualties and littering much of northern Ukraine with their abandoned or destroyed equipment. In the south and east, they have also been mostly static for three weeks now, making incremental gains towards Izyum in the Donbas while actually being forced back in the far southwest towards Kherson.

If the Russian army was in a better state, Putin could draw from troops outside Ukraine to come to the aid of his damaged invasion force. But the opposite seems to be the case. Except for some neo-Nazi mercenaries and a few new units, the Russian leadership instead appears to want to rely on the redeployment of units that lost the Battle of Kyiv to help bolster Russian forces elsewhere.

This is, by any normal military standard, nuts. These soldiers have experienced six weeks of combat, seen many of their fellow troops killed, and come to fear the Ukrainian forces. They need a rest first and foremost before being re-equipped and transported to a new battle area. This process would normally take weeks for an efficient and well-organised army – for the Russians it could well be a logistical nightmare.

Trying to rush Russian soldiers back into this gruesome war quickly would be a sign both of the panic engulfing Putin’s leadership and represent a huge risk for the Kremlin. There are already stories (some involving elite formations such as paratroopers) of soldiers in the Russian army refusing to deploy into Ukraine. Any troops that are redeployed could well be close to breaking down entirely. Human beings can only take the strain of war for so long, and a defeated army takes the strain less well.

This highlights the problem with Russia’s small army. It never had enough troops to take all of Ukraine. It could have enough troops to take parts of the south and east, but will then have no good units left to try and hold these areas. If Russia is to fight a longer war, it will have to do it after it has burned through this original invasion force. This will require the Russian state to raise, train and equip an entirely new army—one that will have to include a large number of conscripts. That will challenge Russian society’s commitment to the war, completely demolish the Russian state’s lie that this is a successful war to liberate Russians and de-Nazify Ukraine, and test the country’s already creaking and unproductive economy.

The basic problem that the Russians face in Ukraine is not that it is a big power, it’s that its army is too small and has too few soldiers that the Russian government trusts to actually fight. It seems the Russian army could be in worse shape that many imagined.

Le Pen’s last stand

Marine Le Pen, if recent polling is to be believed, is rapidly cutting Emanuel Macron’s lead in the upcoming French presidential elections. If she succeeds in gaining sufficient votes this weekend to enter the second round, we should brace for a serious upheaval in French politics at a time of unnerving uncertainty about the global order.

The French press, having forgotten Le Pen for a year, is now energetically reminding voters of her unsuitability for high office. In the public imagination, Le Pen ranges from a modern-day avatar of Joan of Arc to a rancid bigot masquerading as a moderate. Say her name, and people react with fervour: they may despise her, they may revere her, but nobody is indifferent to her.

‘Many French people have the feeling that they have known me forever because they saw me growing up,’ Le Pen told me in her office when we met in February. Dressed in an oat-white suit jacket, navy blouse and black trousers, she was striking and charismatic in person.

As we talked, she puffed on an electronic cigarette. Her spacious office, lit like a television set, was littered with the props of French patriotism: a marble bust of Marianne, the symbol of the republic, modelled on the actress Brigitte Bardot; a tricolore flag; an antique desk. She expressed concern for the health of Queen Elizabeth, whose Covid diagnosis was in the news then. ‘She’s a fighter,’ Le Pen said. ‘One can only have respect for the Queen.’

At 53, the scion of Europe’s most notorious political dynasty has arrived at the realisation that the electorate which has followed her since she was five has only a ‘poor’ understanding of who she really is. The stoicism and stolidity that have made it possible for her to endure years of personal abuse have also allowed her to be defined by others. Now, making her third bid for the French presidency, the previously familiar yet impassive Le Pen said she is determined to ‘show the French who I am’. Her campaign’s unexpected resurgence indicates that her approach is working.

Early in the campaign, Le Pen made a deeply personal pitch at a meeting of her party – recently rechristened the National Rally to purge the neofascist odour of its former name, National Front – at a rally in northern France. She recalled the experiences that shaped her. In 1976, when Le Pen was eight, her family’s home in the 15th arrondissement of Paris was bombed with explosives so powerful that they tore apart the building’s façade. It’s a miracle that anyone survived. But what haunted Le Pen, the youngest of three sisters, into adulthood was the response of France’s haute société cultivée: rather than concern, the insiders and sophisticates radiated contempt for the survivors of a terrorist attack. The unspoken message was that her family deserved what it got – and it deserved it because the head of the family and Marine’s father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, happened also to be the National Front’s founder and president.

That pedigree both stifled and moulded Le Pen. At school, she was shunned and stigmatised by tutors and parents for her father’s politics. She was never invited to her friends’ homes, and they were forbidden from visiting hers, which, for all its outward flamboyance, was imploding. Not long after their home was bombed, the Le Pens relocated to a palatial mansion on a ridge in the private billionaires’ row of Montretout. The house was bequeathed to Le Pen père by an heirless cement baron who also left him his immense fortune. The neighbours held their noses at the new arrivals.

The ‘small humiliations’ that characterised Le Pen’s childhood culminated in the private ‘violence’ of separation at the age of 16 when her mother, Pierrette, a woman of model-good looks, left her husband for a journalist and later posed for Playboy. Le Pen was so wounded that she could not bring herself to see her mother until she was in her thirties. By then, Le Pen herself was divorced and raising three children as a single parent while practising law at the Paris bar. Raised a devout Catholic, she had grown accustomed to being taunted by her father’s enlightened critics for betraying the ‘family values’ he preached to others.

She drifted into politics, she told me, to overcome such attacks and to fight for ‘something more important’. Her name was a gift – she rose rapidly in her father’s party – but also a handicap. In 2012, Le Pen’s first run for the presidency of the Fifth Republic ended in a distant third-place finish. At the last election, five years ago, she lost in a run-off vote against Macron who, despite being a relative unknown, secured his historic victory in no small measure because his opponent was named Le Pen.

‘My fight is a fight against Islamist ideology, which is a totalitarian ideology like Nazism’

The prospect of a Le Pen landing in the Élysée prompted traditionally left-wing voters to half-heartedly cast their ballot for Macron. His victory was animated not so much by hope in him as terror of his opponent. Will the same story play out again in 2022? It helps to understand the history.

The National Front and the ascent of the Le Pens originated in a rebranding exercise in 1972, when Jean-Marie, a former parachutist who had fought in Indochina and French Algeria and served a term in the National Assembly, was invited by the far-right group Ordre Nouveau to sanitise its reputation. To call what emerged from his takeover a coherent ideological movement or even a serious political party is to overthink its purpose. It was a swamp of rage, racism, resentment and anti-Semitic conspiracies: a ramshackle coalition of thwarted, mutually antagonistic intellectuals who theorised about the perils of miscegenation and published jargon-laden theses on subversive Jewish influence.

What held it all together was the pugilistic personality of its leader. Jean-Marie’s success lay not in winning elections – he got 0.74 per cent of the vote when he first ran for the presidency in 1974 – but in converting, through toil and persistence, his peeves and prejudices into blazing political issues. Over the next two decades, he not only built a formidable far-right party in submission to its leader, but also furnished France with a political dynasty.

As he aged, Jean-Marie’s penchant for provocation, particularly anti-Semitic provocation, became a burden for his party and family. He shrugged off the gas chambers as a minor detail, declared that the German occupation of France had not been ‘particularly inhumane,’ and welcomed Ebola as a solution to Africa’s population growth.

When the philosopher Michel Eltchaninoff visited him in 2016, Jean-Marie, then 88 and sitting by a calendar adorned with a bust of Vladimir Putin, dispensed a lecture on the intellectual gap between Europeans and Muslims: ‘Europeans’ intellectual progression forges ahead in a straight line, drops off slightly at thirteen, then continues in an upward trajectory. In the Muslim world, at eleven or twelve, bam! Everything suddenly stops.’ Why, asked Eltchaninoff. ‘Masturbation,’ answered Jean-Marie: ‘As Europeans, we are not prone to this obsession because of our religion… whereas among simple people it is let loose.’

Marine inherited the party’s leadership in 2011. Since then, she has pursued an arduous process of dédiabolisation – ‘de-demonising’ her party and her image – and oriented it towards the new populism. In his affecting memoir Returning to Reims (2018), the French philosopher Didier Eribon writes about the social ‘reconfiguration’ that was occurring under the surface – a metamorphosis ignored by elite political consensus. Eribon had grown up in a family that was miserably poor, occasionally violent, staunchly secular and unwaveringly communist. He left home as a young man, ashamed of his class origins. When he returned, decades later, he discovered that the fashionably left-wing students of his youth were the new bourgeoisie, ‘defenders of a world perfectly suited to the people they had become.’ His mother, meanwhile, abandoned by the left and still cleaning houses, had matured into a strident supporter of Marine Le Pen.

Before the pandemic, many nursed the belief that this year’s elections might lift Le Pen into the Élysée, third time lucky. What made her presidency seem plausible was Macron’s barely concealed disdain for a substantial segment of his compatriots from the moment he took office. France’s aloof and self-cherishing President seldom squandered an opportunity to scoff at the ‘privileges’ of the French working class. A millionaire former investment banker, he exhibited the kind of exasperation that comes naturally to people who believe they have figured everything out. A year after his election, when a young gardener explained to Macron his difficulty in finding work, there was no presidential empathy on offer: not even a perfunctory look of sympathy crossed Macron’s features. Instead, he blamed the gardener for his misfortune.

Despite the favourable climate generated by her opponent’s hauteur, Le Pen struggled until the last minute to procure the 500 signatures from elected representatives across France to qualify for the race. She had begun her appeal in September, but was still a hundred short by the end of February. Privately, she was being told by mayors that they wished to support her. But, because their signatures are made public, they feared reprisals from the government. ‘They all say “I’d like to sponsor you, but I’m afraid my grant will be taken away from me if I ever do”.’ Anne Hidalgo, the mayor of Paris and the Socialist candidate, had more than 1,200 signatures by February despite polling at under 2 per cent – more endorsements from the establishment, the joke went in Paris, than the number of votes she would ever get from the public – but Le Pen’s candidacy appeared to be on the verge of being blocked.

‘Despite the thickness of our skin, we suffer,’ Le Pen told me. ‘We suffer from attacks, we suffer from betrayal.’ The betrayals had been piling up. In the days leading to our meeting, she had sacked Nicolas Bay – a regional councillor in Normandy and until then one of her closest confidantes – for apparently leaking campaign secrets to Éric Zemmour, who at that moment seemed to have outflanked her to the right on Islam and immigration.

Le Pen is contemptuous of Zemmour, a crotchety television pundit and author convicted by a court in January for inciting racial hatred (his third in a long career of provocation). Zemmour burst onto the electoral scene just when Le Pen’s prospects of victory looked brightest. Rather than treat him as a legitimate challenger, however, Le Pen dismissed him as an unfit interloper hyped up by the media to split the French right wing and derail her candidacy just when she has the chance to seize executive power.

‘The emergence of Éric Zemmour is no coincidence,’ she said, claiming that the French media has used Zemmour as an instrument to weaken her. He is, she said, ‘the only chance for Emmanuel Macron,’ and has ‘barely hid’ that fact. ‘His objective is not to win, but to make me lose.’

Still, Le Pen was disconcerted by the ease with which Zemmour had been able to lure away her key supporters. The defection that unsettled her was of her niece, Marion Maréchal. Elected to the National Assembly in 2012 at the age of 22 – the youngest person ever to be voted to parliament in France’s republican history – Maréchal feuded with her aunt, retired from politics in 2017, retreated to Lyon, and founded a school. She emerged last year, having shed her Le Pen surname, to endorse Zemmour.

Maréchal’s action, Le Pen told me, plunged her ‘into an abyss of perplexity’ for two reasons. First, because ‘there are very strong ties of affection between me and the little girl who was Marion, for whom I was very much present in the first years of her life.’ Second, because Zemmour ‘cannot win this presidential election’. The polls back her claim that she, not Zemmour, is ‘best-placed to win against Emmanuel Macron,’ and that Zemmour is ‘completely at the back of the pack of candidates who could possibly prevent Macron from being re-elected’ in the second round. Maréchal’s choice, she said, was ‘incomprehensible’ on both counts.

However much Le Pen professed not to take Zemmour seriously, his entry raised a peculiar challenge for her. She has spent years revamping her political brand, stamping out the anti-Semitic fixations of her father’s generation, and developing a politics that addresses the cultural anxieties of the right by deploying the secular vocabulary of the left. In 2015, she permanently expelled her own father from the party as punishment for another of his grotesque rhetorical forays into anti-Semitic territory.

At that point her base, consolidated over decades, had nowhere else to go. Emancipated from the duty to pander endlessly to its prejudices, she was free to assail Macron from an anti-corporatist position. The ideology for which the French President stood, she said, ‘far exceeds mere globalisation’: its objective is ‘to encourage nomadism, the permanent movement of uprooted people from one continent to another, to make them interchangeable and, in essence, to render them anonymous.’ Those words were not so different from Theresa May’s exhortation that ‘if you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere’.

Le Pen spoke of and for the blue-collar communities abandoned by the chic ruling elites. She attacked the ‘Europeanist monster being built in Brussels, which defines itself, in a semantic fraud, as “Europe”, but is nothing less than a conglomerate under American protection, the antechamber of a total, global world state.’ Her philippics against immigration were accompanied by calls for the fortification of equal citizenship predicated on the rule of law and assimilation, and her speeches liberally quoted from socialists and heroes of the Third Republic: Clemenceau, Jaurès, and Zola. Anyone from anywhere, she told me, could be French, provided he or she merged into France.

When I asked her if Islam was compatible with Frenchness, her answer was emphatic and expansive: ‘Yes,’ she pronounced. ‘Nothing in Islam makes this religion incompatible. My fight is not a religious fight. My fight is a fight against Islamist ideology, which is a totalitarian ideology like Nazism. And this ideology is contrary to the French constitution. But once again, the Muslim religion is a religion like any other and I have no war to wage against a religion in France.’

In a country that has endured beheadings, stabbings, and mass shootings by self-proclaimed Islamists, her position, despite its allusion to the totalitarianism of the Third Reich, is not so radically different from Macron’s condemnation of ‘Islamist separatism’. Her belief that Islam, in its private religious form, is completely congruous with the French identity accords with French republican tradition.

But after all her work to detoxify herself and her party, and after making considerable inroads into the left’s terrain, she faced the possibility of being deserted by her traditional voters. Zemmour’s astringent oratory, employed in service of his unapologetically sulfurous ultranationalism, was draining away supporters from her strongholds. His maiden presidential event, held on the same day as hers, drew a much larger crowd.

Then Vladimir Putin intervened. Macron’s candidacy, already ahead in the polls, was instantly bolstered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. And Le Pen and Zemmour found themselves acutely vulnerable to accusations of being marionettes of Putin and his strongmen epigones in Eastern Europe.

In 2014, Le Pen’s party had received loans from an obscure Russian aircraft parts company. Her current presidential campaign is financed by borrowings from a Hungarian bank. The reason she uses foreign financial institutions is that, despite guarantees from the French state to repay loans taken by political candidates who obtain a certain percentage of the vote, no French bank will touch her party. But could that detail, always little appreciated, wash away the public perception, especially in this febrile moment, that she is beholden to foreign authoritarians?

Macron, by contrast, grasped the opportunity. He engaged in high diplomacy at a long table in Moscow and played a gallant defender of Ukraine against Russian aggression. But the permanently airborne President, having cast himself as an international statesman above petty domestic politics, had failed dismally to avert a shooting war. As the conflict intensified, his numbers became stagnant and Le Pen’s surged.

She has managed thus far to survive – and rise – despite her affection for Putin. Macron’s speeches are already replete with references to the Russian President and his ‘indulgence’ by French politicians, and he is certain to make Putin the dominant theme of his debate against Le Pen. Yet she did not adjust her opinions to suit the prevailing mood when I asked her, two days before war erupted in Ukraine, to name the leaders she most admires. She answered without hesitation: Narendra Modi, Boris Johnson, and Vladimir Putin. ‘I have respect for Vladimir Putin because he defends the interests of Russia,’ she clarified, adding that she also admires Angela Merkel for the same reason: Merkel may have gone against France, but she ‘defended the interests of Germany’. She may be less forthcoming now.

Once Russia launched its military campaign in Ukraine, Le Pen was one of the first to condemn it ‘in the strongest terms.’ When I contacted her after our meeting, she told me that Russia’s conduct was ‘not defensible’: ‘the sovereignty of nations is not negotiable, the freedom of nations is not arguable.’ She even offered assistance in taking refugees from Ukraine, while reiterating that she still believes in ‘independence, equidistance and constancy in our defence policy.’ Meanwhile, her party has reportedly pulped 1.2 million leaflets containing an image of Le Pen shaking hands with the Russian President.

Le Pen did not exude the same warmth for the current American leadership. She was consistent in her coldly realistic assessment of relations with Washington. ‘I have a lot of friendship for the American people,’ she said, but not so much for their leaders. When ‘they use the extraterritoriality of American law’ to harry other states, ‘they go too far’. France must belong in neither camp, Le Pen believes, and should guard its interests by maintaining ‘relations that are at a respectful equidistance’ with both Moscow and Washington. This is not a fringe view in French politics, which has always contained a thick streak of scepticism towards America, but the audience for it may have shrunk in recent weeks.

From a pre-war, pre-pandemic vantage point, 2022 looked, at least on paper, like Le Pen’s year. She had come out of her father’s shadow, effectively decapitating and banishing the old bigot into retirement. She had deodorised the family name to the best of her ability and instilled discipline in her party. She had reinvented herself as the champion of the left-behinds and sublimated the neglected grievances of her supporters into a cohesive ideology to reclaim France.

Ludwig Knoepffler is a London-trained political scientist from a cosmopolitan family who recently left a lucrative career in the private sector to work for the National Rally. He told me that what drew him to Le Pen was not something grand but something rather basic: her unwillingness to give up. It’s wrong to believe that she is animated by a hunger for power, he told me. ‘She could have inherited a small world that worshiped her family name and remained confined to it,’ an Asian diplomat who has interacted with her explained to me. ‘Instead, she rejected that world and chose to engage with the hostile universe’ to ‘broaden her base’. Jean-Marie was a self-amusing provocateur who was never interested in winning power. ‘Marine is protective of the French people the same way a wolf mother is protective of her children,’ Knoepffler told me. ‘That love makes her compassionate and kind, but also fierce and dangerous.’

Should Le Pen lose this election – an outcome that, despite her performance in opinion polls, is very likely – she will have stacked up three consecutive defeats. If she makes it to the second round, she may survive. But before she can mount another campaign in five years’ time, when she will be 58 – still young by the standards of French presidential elections – she will have to first unify a right-wing fractured by Zemmour, who appears determined to displace her as the champion of the left-behinds. Rather than directing a lofty fight from the presidential palace to protect what she calls ‘the interests of France,’ she will be forced to wage intra-ideological trench warfare to preserve her party and its support base. She has done it before, and it would be foolhardy to bet against her ability to do it again. But even if she succeeds in that battle, she may ultimately have to cede the crown to the younger generation.

National Rally, full of new talent, will not vanish if and when Le Pen loses in the second round. Jordan Bardella, Le Pen’s pugnacious 26-year-old deputy, is viewed by many as the next leader. His approach to politics is more reminiscent of Jean-Marie than Marine. This is why, even if she quits the presidency of her party, her aides say that she will be forced by the party rank and file to stay on in an honorary role – if only to temper the destructive impulses of her ‘children’ in the same way in which she tamed her father. ‘If she does not become queen,’ a supporter of Le Pen’s told me, ‘she will at least end her career as a kingmaker’.

A version of this article first appeared in The Spectator World edition.

The terrifying neo-Nazi mercenaries being deployed in Ukraine

Given how the Kremlin is so determined to portray Ukraine as a hotbed of Nazis, it is tragically ironic not only that its own forces seem determined to recreate some of the horrors of the German invasion in the second world war, but also that it is so willing to use its own fascists in pursuit of its war.

The latest unit to hit the news is Rusich, a unit affiliated to the infamous mercenaries of Wagner Group. Its name simply means a member of the old Rus’ people, and speaks to its inchoate ideology, a mix of traditional Slavic (and Viking) paganism, Nazism, and extreme Russian nationalism.

Originally drawn largely from neo-Nazis out of the St Petersburg nationalist underground scene, in 2014 Rusich emerged as one of the ‘volunteer battalions’ in rebel-held parts of Ukraine’s Donbas region. Moscow neither created nor controlled Rusich, but nor did it do anything to prevent its emergence: the first months of the Donbas war were essentially ones in which the Russian government was happy to watch and see what happened.

Rusich seemed to revel in their impunity and their reputation for violence, mutilating and burning the bodies of the dead

By summer, the Kremlin was faced with a choice of letting Kyiv reassert its control over the rebel regions or involve itself directly, and it chose the latter course. As Russian troops started to appear in the Donbas, the thuggish array of local militias were increasingly forced to accept Moscow’s direct or indirect control. Some resisted – and a number of warlords ended up dying in ‘mysterious’ assassinations – but Rusich seems to have had no qualms in being incorporated as a deniable weapon of the Russian state.

They seemed to revel in their impunity and their reputation for violence, mutilating and burning the bodies of the dead and even putting videos of their atrocities online. One of their commanders even boasted of cutting the ears off the dead. Rusich became the focus of a small, disturbed but genuinely fervent cult, presenting themselves as modern-day Vikings (part of the roots of the Rus’ state being, after all, from early medieval Nordic raiders and traders who chose to carve out principalities in the Slavic lands).

Never a large group, they had a disproportionate reputation for ferocity as much as firepower. As they became more tightly controlled by the state, albeit at arm’s length through Wagner, they cropped up in Syria. And as the Kremlin desperately looks for more soldiers to deploy to Ukraine, it looks as if they are back here, too.

Their own social media presence – what noxious force these days does not announce its atrocities online? – suggests they will be deployed against the city of Kharkiv, one of the cities key to control of the contested east of the region. There are no more than a few hundred troops in the Rusich group, so their direct impact on the battlefield is likely to be limited, but their psychological impact may prove more significant.

What can one read into Moscow’s increasing dependence on units known to have poor discipline or an active delight in committing war crimes, from the Wagner Group’s mercenaries, to the Chechen National Guardsmen some have accused of playing a key role in the Bucha massacre, and to neo-Nazi groups such as Rusich? (It is worth noting that there are other, similar groups.) It may simply be that Moscow cannot be picky as it needs all the fighting men it can get. But it is more likely that it also sees some advantage in trying to terrorise the Ukrainians, hoping that this will undermine their will to resist.

If the evidence so far is anything to go by, the exact opposite is true. Anger and outrage at Russian atrocities are uniting and inspiring the Ukrainians as never before.

Meanwhile, it is hard not to see a growing echo of fascism in Putin’s regime. This is not just in its choice of instruments, although it is worth noting that the Wagner Group got its name from the call-sign of its skin-headed commander, Colonel Sergei Utkin, who himself is tattoed with Nazi iconography.

Rather, it is in its dark turn to outright authoritarianism, Putin’s stark demands that Russians decide whether they are ‘patriots’ or ‘traitors,’ and his refusal to acknowledge that Ukrainians are even a people in their own right. The war at home has been symbolised with a lightning flash style ‘Z’, and the bitter Russian joke goes: where is the other half of the swastika? Oh, it’s been stolen. A mix of fascism and kleptocracy, after all, are becoming the last defining features of Putinism in its final, morbid stage.

Boris and Scholz parade the new Europe

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has changed Europe forever. That was the argument that Boris Johnson made on Friday when he held a joint press conference with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz. One of the changes Johnson was keen to emphasise was that European leaders are united in their support of Ukraine and against Putin. This, he argued, was one of the ways in which the Russian President had failed: he had sought to create divisions in Europe, but had ‘demonstrably failed’. ‘The Europe we knew just six weeks ago no longer exists: Putin’s invasion strikes at the very foundations of the security of our continent,’ he said, adding: ‘Putin has steeled our resolve, sharpened our focus, and he has forced Europe to begin to rearm to guarantee our shared security.’

Johnson claimed Germany would stop importing Russian gas by 2024, something Scholz did not repeat

He congratulated Scholz on what he called the ‘seismic’ step of moving Germany away from Russian hydrocarbons. But there were still differences between the two leaders, despite his insistence that the pair had agreed on almost everything in their talks. For instance, Johnson claimed Germany would stop importing Russian gas by 2024, something Scholz did not repeat. Instead, Scholz explained that it would take longer to end Russian imports of gas than for coal but that he was ‘optimistic’ about getting ‘ride of the need of importing gas from Russia very soon’. The German Chancellor also said criticism of Emmanuel Macron for talking to Putin was ‘unjustified’, while Johnson said he didn’t think such negotiations were full of promise because the Russian President can’t be trusted.

But the commitments by Germany to change its energy market so that it doesn’t rely on Russian imports do back up Johnson’s central thesis about Europe fundamentally changing. The hope now is that Putin’s miscalculation will be felt not just from the huge troop losses, but also when countries like Germany turn their backs on the energy supplies they had come to rely on.

This year’s best Easter eggs

Here to separate the good eggs from the great eggs, we’ve tasted the Easter treats from the UKs favourite retailers. The 2022 eggs range from the innovative to the slightly baffling but the good news is there’s great options here for every taste and budget.

Autore Milk Chocolate Egg with Pistachios, £19.70 – Delicaro

Upper crust food merchant Delicario is selling a selection of eggs made by Campaian cocoa ultras Autore Chocolate. This is the sort of website where you can buy Japanese beef that was pampered to death and special tuna fed exclusively on truffles (probably) so expectations are high.

The thick, milk chocolate comes with a generous pebble-dashing of Bronte pistachios, nuts of protected origin grown on the slopes of Mount Etna. The chocolate isn’t overly complicated but it’s creamy and decadent and nostalgia-inducing in the way only sweet milk chocolate can be, so no complaints there. The depth and textural contrast provided by the pistachios – which taste exactly as fancy as you’d want them to – add up to a seriously satisfying experience. Could only be improved by a little glass of cold grappa on the side. Not for the kids, obviously.

Score: 9/10

Perfect for: Foodies and anyone with opinions about pesto

No.1 Hidden Truffles Blonde Chocolate Easter Egg, £10 – Waitrose

When you open the box there’s a little bit of white text inside that says ‘LOOK UNDER THE EGG TO FIND THE HIDDEN TRUFFLES!’ which somewhat removes the thrill of the chase but never mind. The four little spheroids included are sprayed gold and filled with salted caramel. The human brain is not evolved to cope with the one-two punch of sugar and sodium so they are of course frighteningly delicious.

The blonde chocolate used in the egg itself is made by slowly caramelising white chocolate. This adds Maillard reaction complexity and offers a general upgrade on common-or-garden white chocolate. The rich caramel flavour is countered here with a little more salt and some flakes of crunchy feuilletine but it’s still going to be too cloying for some palates. Very nicely put together but one for the sweet toothed – you know who you are.

Score: 7/10

Perfect for: White chocolate diehards and people who like Caramac bars

Belgian Milk Chocolate Tiramisu Egg, £8.00 – Sainsbury’s

This tall, pointy number from Mr Sainsbury is painted with a go-faster stripe of pleasantly bitter cacao nibs. The fragments of dried cacao give contrast and definition to the unembarrassedly sweet chocolate egg, though they are little grainy on the palate. Some powdered Brazilian coffee in the mix promises to approximate tiramisu but it doesn’t shout quite as loudly as you’d want it to over the other ingredients.

The overall experience is somewhere between a grownup pudding and an old-fashioned milk chocolate sugar fest. It will make a nice gift for the Espresso Martini drinker in your life. Solid stuff.

Score: 6/10.

Perfect for: Breakfast or cocktail hour

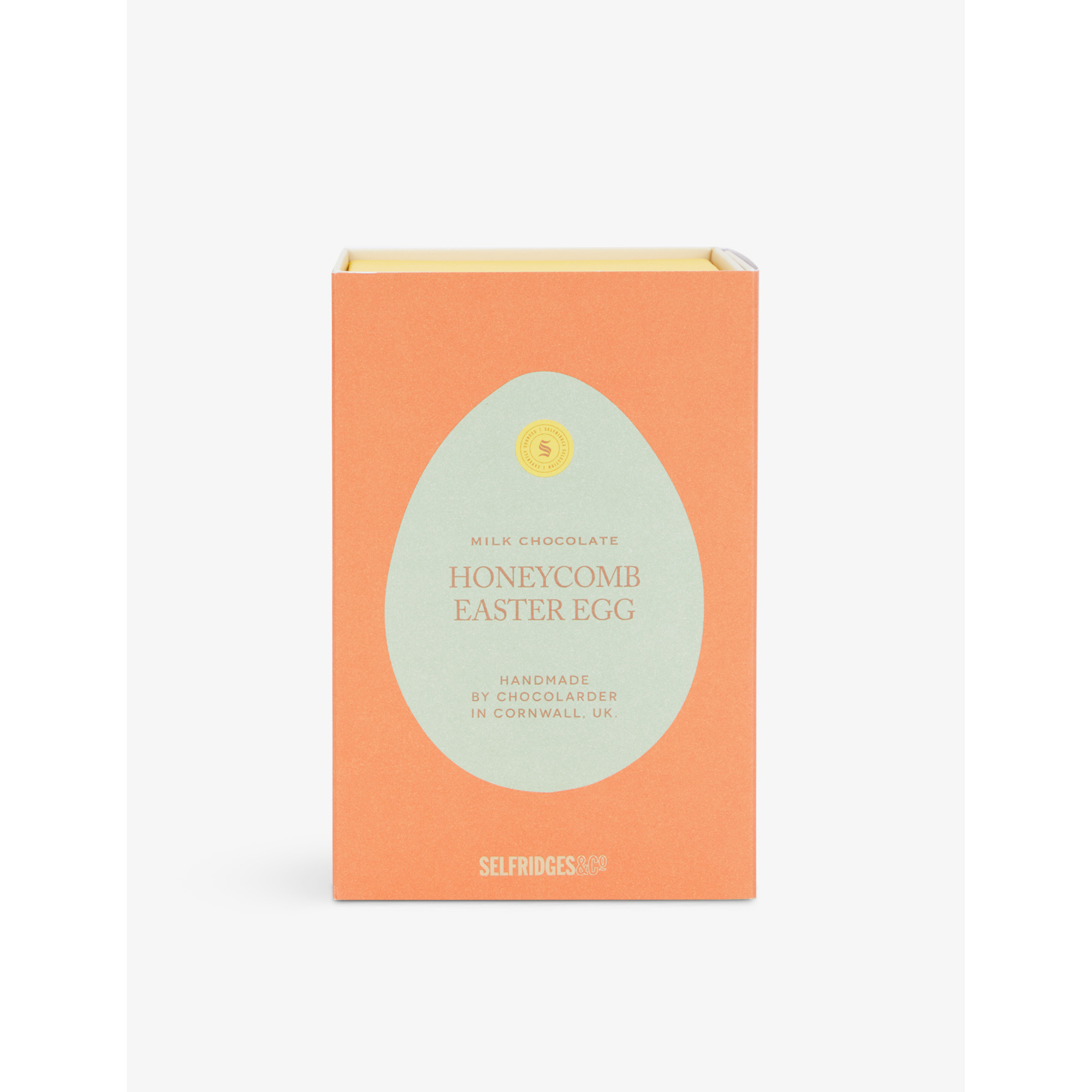

Milk Chocolate Honeycomb Easter Egg, £22.99 – Selfridges

In comparison to some other eggs on the list, this is a pretty route one offering. No novel flavours, no truffles – concealed or otherwise – just a glossy egg with embedded crystals of honeycomb. But really, that’s more than enough because this is top drawer. It reminds you that chocolate is a fermented foodstuff like coffee, or cheese, packed with layers and complexity. This isn’t exactly dark but it does have an earthy side that balances perfectly with the sweetness and some very nice dried fruit notes. A class act.

As you’d expect from the yellow bag people the packaging is impeccable. In addition to looking swish the box lists the origin of the beans and the names of the people that grew them, which is a nice touch. Honourable mentions go to the oat chocolate version which is suitable for vegans and milk-dodgers and is likewise excellent.

Score: 10/10

Perfect for: Serious chocolate botherers

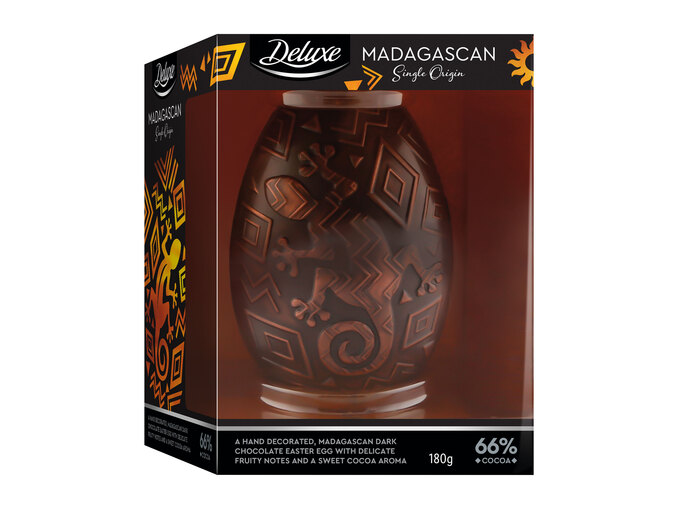

Deluxe Single Origin Easter Egg, £4.99 – Lidl

Lidl’s premium offering for 2022 is a single origin egg that’s a respectable 70 per cent cocoa. You get a choice of Ecuadorian or Madagascan beans which come embossed with a vaguely pre-Columbian metallic panther and lizard respectively. Quite stylish, actually. The Ecuadorian tested here is densely aromatic with lots of soft spices, pine nuts and a bit of cigar box on the nose. The shell has a nice snap to it and melts well on the palate with a satisfying bitterness in the finish.

You’re dealing with pretty substantial dark chocolate here but it’s not one of those overly dry, woody numbers that you have to pretend to like because it’s grownup. Everything balances very nicely. This isn’t just good for the price, it’s a stunning piece of chocolate by any measure.

Score: 8.5/10

Perfect for: Food geeks and bargain lovers

Tony’s Chocolonely Egg-stra Special Chocolate Eggs, £3.75 – Ocado

This tray of miniature eggs comes from the Dutch firm committed to eliminating slave labour and child exploitation in the cocoa business, a cause we can all get behind. The dozen individually wrapped chocolates are tiny, ovoid renderings of Tony’s various bars which range from the ingenious – pretzel and toffee – to the vaguely troubling – white chocolate with raspberry and popping candy. There’s something for everyone, even those of slightly outré tastes, so this is a great option for bringing to the office.

In addition to its efforts to clean up the chocolate industry, Tony’s is now B Corp certified, uses only recyclable packaging, and only works with beans that volunteer to be turned into chocolate – so you can feel good about indulging this Easter weekend.

Score: 6.5/10 an average across all 10 flavours

Perfect for: Kid’s parties, colleagues, and anyone with a heart

The Drippy Egg, £10 – Marks & Spencer

A decidedly original offering from M&S, each egg comes is finished with layers of pastel coloured Belgian chocolate poured over the top. It looks nice, a bit like one of those Ai Weiwei vases but without the implied criticism of the CCP. Unfortunately, it’s a bit flat flavour-wise. The shell is pleasant enough but lacks those secondary and tertiary flavours that stand out in a really excellent bit of chocolate.

Still, this is the style we all grew up eating and will satisfy milk chocolate fans of an arty persuasion. Fine work and definitely deserving of an extra point for the presentation.

Score: 5/10

Perfect for: Dairy Milk lovers with Tate memberships

Luxury Dark Chocolate Easter Egg With Truffles, £60 – Charbonnel et Walker

Representing the highest of high-end, this Bond Street chocolatier has been supplying the upper crust with sweets since the 19th century. This dark chocolate is the style for which the house was historically know and even given the price tag it doesn’t disappoint. The box comes stacked with individual creations from the repertoire including the famous boozy truffles but the real star is the egg itself. It’s compact but dense and beautifully textured, neither too bitter or too sweet and melts nicely on the palate without feeling heavy or cloying. It tastes of hazelnuts, black tea, dried berries and a kaleidoscope of other little flavours that change over time. This is chocolate in four dimensions.

If you’re really looking to push the boat out you can pick up this thoroughbred oeuf as part of the Charbonnel et Walker Family Easter Hamper, yours for £140. This statement piece of a chocolate box comes with Peter Rabbit branded treats for the kids and Pink Marc de Champagne truffles for the grownups. Very nice too.

Score: 10/10

Perfect for: Someone you’re trying to impress.

Hand Finished Hot Cross Bun Easter Egg, £6 – Co-op

Lo and behold, the hot cross bun is now available in Easter egg form. This fair-trade chocolate treat promises all the fun of the iconic bread-roll-based pudding and honestly, it really delivers. The shell itself is a little on the thin side but the evocative smell of raisins and orange peel hits you as soon as you crack into it, so it scores well on the nostalgia front. Ginger and cinnamon bring warmth and lift that stops the white chocolate getting too sickly and adds a novel dimension.

Honestly, the only way this could be easily improved is if it incorporated bacon – because as we know the only really sensible thing to do with a hot cross bun is make a breakfast sandwich with it.

Score: 7.5/10

Perfect For: Bun baddies and novelty seekers

Rishi’s wife changes tack on tax

This evening Rishi Sunak’s wife Akshata Murty has announced that she will pay UK taxes on her overseas income, following a public backlash after reports of her tax arrangements as a non-domicile emerged on Wednesday night. The change in tack comes after the Chancellor used an interview with the Sun newspaper to accuse political opponents of ‘smearing’ his wife in order to hurt him.

In a statement, Murty said that while her tax arrangement up until now was ‘entirely legal’, it had ‘become clear that many do not feel it is compatible with my husband’s role as Chancellor’ and she ‘will now pay UK tax on an arising basis on all my worldwide income, including dividends and capital gains, wherever in the world that income arises’:

‘Since arriving in the UK, I have been made to feel more welcome than I ever could have imagined, in both London and our home in North Yorkshire. This is a wonderful country. In recent days, people have asked questions about my tax arrangements: to be clear, I have paid tax in this country on my UK income and international tax on my international income. This arrangement is entirely legal and how many non-domiciled people are taxed in the UK. But it has become clear that many do not feel it is compatible with my husband’s role as Chancellor. I understand and appreciate the British sense of fairness and I do not wish my tax status to be a distraction for my husband or to affect my family. For this reason, I will no longer be claiming the remittance basis for tax. This means I will now pay UK tax on an arising basis on all my worldwide income, including dividends and capital gains, wherever in the world that income arises. I do this because I want to, not because the rules require me to. These new arrangements will begin immediately and will also be applied to the tax year just finished (21-22). Until now, I have tried to keep my professional life and my husband’s political career entirely separate. Since Rishi entered parliament, he has not involved himself in my business affairs and I have left politics to him. When I met him we were 24 year old business school students, living in another country, and had no idea of where life would take us. Rishi has always respected the fact that I am Indian and as proud of my country as he is of his. He has never asked me to abandon my Indian citizenship, ties to India or my business affairs, despite the ways in which such a move would have simplified things for him politically. He knows that my long-standing shareholding in Infosys is not just a financial investment but also testament to my father’s work, of which I am incredibly proud. My decision to pay UK tax on all my worldwide income will not change the fact that India remains the country of my birth, citizenship, parents’ home and place of domicile. But I love the UK too. In my time here I have invested in British businesses and supported British causes. My daughters are British. They are growing up in in the UK. I am so proud to be here.’

Will the statement be enough to stem the row? That’s unlikely. Many have already made up their mind. But after Sunak allies suggested that tax questions were illegitimate, it shows a change in tack when it comes to shoring up the Chancellor’s position.

How much is Britain’s inflation rate rising by?

How is the UK’s economic bounce back from the pandemic years going? Next week the Office for National Statistics will provide us with a host of new monthly data, including an economic growth and labour market update for the month of February and the headline inflation rate for March.

The inflation rate is the real kicker. While GDP and labour market headlines from February will allow us to further gauge how strong the economy was at the start of the year, March’s CPI rate will factor the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This has undoubtedly had an impact on prices: the cost of energy, in particular.

There’s little doubt that the inflation rate is going up again. But by how much? Over at Deutsche Bank, the research team is projecting the year-on-year CPI rate will rise significantly, from 5.5 per cent in February to 6.7 per cent in March (this projection lines up with the consensus too).

The unemployment rate gives some cause for hope

Meanwhile, Deutsche’s predictions for February GDP growth sit slightly above the consensus: at 0.3 per cent compared to 0.1 per cent. Still, even the Bank’s forecast is rather lacklustre, given 2022 was supposed to be the UK’s big year of economic revival. Deutsche’s yearly forecast for growth is still at 3.8 per cent, ‘sitting almost a full percentage point below consensus from late last year.’

Lower growth than predicted and higher inflation than politicians know how to handle both add to the dangerous recipe of ‘stagflation’. Yet the unemployment rate gives some cause for hope: with the headline rate already back to pre-pandemic level lows, the consensus remains that it will stay under four per cent in next week’s updates.

Monthly data, of course, can only tell a fraction of the story, and only so much can be gleaned about wider trends. But with economic growth for this year already forecast downward in the Spring Statement, and inflation on the rise for months now, next week’s data updates are likely to confirm what is already suspected by Deutsche and others: that our economic circumstances are likely to worsen before they improve.

The Spectator’s 2022 internship scheme is now open: no CVs, please

2023 scheme is now live, click here

The Spectator’s internship scheme for 2022 is now open. We don’t ask for your CV and anonymise all entries – making our scheme the most genuinely open (and competitive) in national journalism. In our game, all that matters is talent – and we put a lot of work into finding that talent. Our internship scheme pays (but not very much) and we even provide help with accommodation for those who need it.

Our scheme is famously tough, so those who get a place often get job offers elsewhere. The Spectator will only ever be as good as the people we hire – and we find this method of hiring interns casts a net wide.

Over the years our interns (some of them now working at The Spectator) have been Lidl store managers, Oxford dons, career switchers, students (two have worked with us this year while completing their course), stay-at-home mums, teachers and lawyers. We recognise that a CV is a snapshot of how well (or not) things were going for someone at a particular point in their life and does not reveal true talent or potential.

We offer four types of internships (you can apply for as many as you like)

- Magazine

- Steerpike Political Mischief Internship

- Broadcast

- Research and Data

1) To apply for a magazine internship, complete at least two tasks from Part A and at least three tasks from Part B.

Part A:

- Name three ways we could improve a) our magazine and b) the website

- Suggest five people to get for either a diary or an interview – and any ideas on how you would get them

- Suggest a cover story and some potential authors

- Write a 300-word blog for Spectator Life or Coffee House

- What was your favourite Spectator magazine feature in the last year and why?

- Find a grammatical or factual error in anything the editor has written

- Suggest three new headlines for this Evelyn Waugh piece

Part B:

- Write an entertaining 150-word letter to The Spectator in response to a recent article

- Write a 250-word review of a book that hasn’t been reviewed yet in The Spectator

- Should Gen Z care about inflation? Discuss in 400 words

- In 300 words, make the case for the country which has had the most or least successful Covid policy

- In 350 words, make the case for The Spectator joining the metaverse

- Submit an entry for one of The Spectator’s recent writing Competitions (page 58 in this week’s magazine)

- Submit three possible entries for a Barometer column

- Choose an article from the foreign press on a subject The Spectator has yet to cover. In 200 words, outline how we should cover the subject

- Write a 350-word Notes On – relating to an intriguing subject that hasn’t yet been covered in the magazine

2) To apply for a Steerpike internship for Political Mischief, answer at least two questions from below:

- Which member of the Cabinet would win Squid Game and why?

- If you were Matt Hancock’s adviser, how would you plot his political comeback? Explain in a 300-word blog

- What is the most common name for a Tory MP and for a Labour MP?

- Pork barrel politics: Which constituency has received the most help from the government? Explain in a 300-word blog

- Write a 300-word Steerpike on a subject of your choice

- Send three topics for a Freedom of Information request

- Macron or Trudeau? Compare in a 300-word blog

3. To apply for a broadcast internship do at least one of the below tasks:

- Produce and present a podcast (maximum seven minutes) profiling a cabinet minister. Edit it using a free trial of Hindenburg

- Produce and present a short video making the case for or against a no-fly zone in Ukraine. Edit it using a free trial of Premiere Pro

And at least three of the below tasks:

- List potential guest line-ups for an episode of The Edition, based on three stories from a recent issue of The Spectator (one must be current affairs). Briefly explain why you chose each guest

- Point to three things we’re doing wrong with our current podcasts or Spectator TV

- Draft questions for a segment of The Edition, where Rod Liddle and Henry Kissinger are the guests, based on this article by Rod

- Make a clip and draft a tweet to promote a conversation from Spectator TV on Twitter. Here’s a previous example

- Pitch a new podcast or Spectator TV show

- Choose a song to play out an episode of Coffee House Shots. Tell us which episode, and why you chose the song

4. And for a research/data journalism internship, do these tasks:

- Please replicate any two of The Spectator’s data hub graphs using Datawrapper

- Find socioeconomic support for any two Beyonce or Destiny’s Child lyrics

- Find the equivalent of at least five of these for England or the UK

- How many times more likely are England’s poorest to die from avoidable causes than England’s richest? And how has this changed since 2001? You can show your answer in a graph

- (optional) Create a choropleth map with Datawrapper showing the vote percentage for Macron and Le Pen in each French department for the second round of the 2017 election

- (optional) Using Python and the Yahoo! Finance wrapper, create an automatically-updating Datawrapper graph for a commodity or stock price affected by the war in Ukraine

If you can do the Python task (or how to query Google Analytics) then you can win a paid internship place immediately as we have plenty of work for those who know how to analyse data. Email Fraser directly (and copy in internship@spectator.co.uk)

Send your answers with a covering letter and absolutely no CVs to internship@spectator.co.uk. Please write in the subject line which internship you are applying for. The deadline for applications is Friday 27 May but early applications are encouraged. I’d urge those who didn’t get through last time to have another go. The difference between the ten we select and the next, say, 50 is agonisingly small.

All candidates are assigned a city name (Tokyo, Perth etc.) and their applications are judged anonymously. We typically get 200 entries, which are whittled down to a top 50 then a top 25. These are scored out of 100 by three Spectator staffers and averages taken: offers are made to the top ten.

If you’re interested in a career in journalism – and want to test your ability in the most competitive application of its kind – then do consider us. And Oxbridge students: we’re serious about that no-CV thing. Any sneaky references (‘I edit my university newspaper, Cherwell’) etc. will be noticed.

Finally, while we do invite applications from everyone, we do ask:

- Not to bother if you have a job lined up as you’d be taking the space of someone for whom this could be life-changing

- We often recruit from our interns so we ask for you not to apply if you have more than two years of education left to run

- Have faith in yourself if you do not have connections or experience. Read Katherine Forster’s story. And in her words: ‘Just go for whatever you want to do. However unlikely or impossible it might seem, you never know what may happen.’

NOTE: Interns typically spend five days in the office (do tell us if there’s a specific week you’d like to work between June and October) and will be asked to do a wide range of tasks. These include some menial tasks (which all of us do at The Spectator); if this puts you off, don’t apply! Remedial support is available for PPE students.

Sulky Sunak has scuppered himself

There is a scene in one of the Lord of the Rings films in which kindly Bilbo Baggins becomes contorted with fury as he glimpses the ring around the neck of his young cousin Frodo and tries to snatch it away. This shocking loss of emotional balance reminds us of the old saying that power corrupts. It also puts one in mind of the recent snappy and petulant public displays of the hitherto mild-mannered Rishi Sunak.

In his latest interview, the Chancellor has even started referring to himself in the third person – always a psychologically revealing moment in the life of a celebrity. ‘She’s not her husband’s possession,’ he said of his wife Akshata Murty, ‘Yes he’s in politics and we get that but I think, you know, that we get that she can be someone independent of her husband,’ he told the Sun.

This interview, in which he hits out at an ‘awful smear’ from Labour, comes as his allies brief other newspapers that they think 10 Downing Street is in fact behind a co-ordinated campaign against him.

Sunak’s shocking loss of emotional balance reminds us of the old saying that power corrupts

That such thoughts are being aired within Team Rishi is highly revealing; it implies that rumours of bad blood with Team Boris next door are well-founded. It all adds up to a picture of someone who has become convinced that he was about to become Prime Minister and is struggling to deal with having had the ring of power apparently within his grasp, only to see it fall out of reach again, perhaps permanently.

Another report suggesting Sunak thinks he could be the victim of a criminal ‘hit job’ is yet more evidence that introspection has taken the place of effective communication in the Chancellor’s modus operandi. At the start of February, on the day of Munira Mirza’s resignation as Johnson’s policy chief, ostensibly over his Commons claim that Keir Starmer had failed to prosecute Jimmy Savile, most Westminster observers thought the PM was doomed. Sunak, at Johnson’s lowest ebb, grandly declared: ‘I wouldn’t have said it’.

This was surely almost as much of an invitation to mutinying Tory MPs to remove Johnson as Geoffrey Howe’s famous ‘broken bats’ resignation speech was an invitation to their forebears to remove Margaret Thatcher. But Howe’s attack worked and Sunak’s didn’t. The main difference of course was that Howe was entirely focused on removing the incumbent, while Sunak’s eye was mainly on the succession. So Howe attacked front-on while Sunak just gave a coded nod to the insurrectionists.

Since then, everything has fallen apart for him. All his strengths have become weaknesses. His spring statement fell awkwardly between two stools: he couldn’t decide on whether to carry on playing Robin Hood or switch into Sheriff of Nottingham mode. His slick infographics and photo opportunities have been turned against him too, as in the now notorious shot of him filling up a Kia Rio that turned out to belong to a Sainsbury’s staff member. That led to questions about what cars he did in fact own and his answer that he drove ‘a Golf’ was followed by revelations that he owned a fleet of high-end vehicles.

From there it was but a short hop into the overall financial circumstances of the Sunak family and revelations about his billionaire wife’s non-dom status. Speculation about Sunak himself holding a United States ‘green card’ at one time, implying loyalty to another country, may prove to be more toxic still.

Old Westminster hands certainly detect a brutally effective Labour attack grid in operation – no doubt the end product of months of careful information-gathering and planning. Having weakened Boris Johnson over partygate, knocking the shine off his likely successor became a strategic opposition priority. But it may well be that Sunak has been caught in a pincer movement, with allies of the Prime Minister also keen to take him down a peg or two over his perceived lack of loyalty to their newly reinvigorated boss.

Ultimately his best hope is to knuckle down for a long, hard slog as a Chancellor in charge of repairing the weakened public finances. Cutting out interviews in which he comes over as sulky would be a good place to start.

The Guardian goes for J.K. Rowling

It seems that taking gratuitous swipes at J.K. Rowling has become something of a competition for liberal broadsheets on both sides of the pond. First, the New York Times took a potshot at the Harry Potter creator for its new marketing campaign trumpeting ‘independent journalism.’ And now the Guardian – keen to prove that, it too, is achingly right on – has published a piece which implies that Rowling’s views on same-sex spaces are somehow more controversial than domestic abuse. Grim.

The latest jibe at Britain’s greatest living writer came in a piece detailing the controversies around the production of the Fantastic Beasts film. Film critic Ryan Gilbey noted that ‘one of its stars, Johnny Depp’ left after losing a libel case which referred to him as a ‘wife-beater’ following accusations of domestic violence made against him by his ex-wife Amber Heard. Another star, Ezra Miller, was videoed grabbing a woman by the throat in a bar in Reykjavik and was last week arrested for disorderly conduct in a Hawaii karaoke bar.

For Gilbey and the Guardian though, alleged wife-beating and choking women in public were ‘small beer’ compared to Rowling writing about own personal experiences and views on the transgender debate. Having listed the accusations facing Depp and Miller, Gilbey claimed that:

This all feels like small beer compared with the controversy that has swirled around Rowling over the past few years, ever since a long essay she wrote about her gender-critical feminism put her at the centre of the row about trans rights. The world of Harry and its Fantastic Beasts spin-offs has undoubtedly been marred by this.

Are words really more harmful than actions? Quite a statement from such a leading organ of PC opinion. Following an online backlash, the Guardian has now been forced to change its article, noting in a footnote that: ‘this article was amended on 8 April 2022 to rephrase a sentence that inadvertently downplayed the actions of Depp and Miller.’ Yet as writer Sarah Ditum points out, the piece also celebrates fans ‘removing her from the picture’ and ‘taking ownership’ of Rowling’s work – just like the NYT’s campaign to ‘imagine Harry Potter without its creator.’

Erasing women – how progressive.

How Israel’s Prime Minister got burnt by bread

Jerusalem

For nearly ten months now, ever since his surprising elevation to the Israeli prime minister’s office, Naftali Bennett has been focused mainly on one thing. He has been trying to prove to Israelis that he can be every bit the master statesman his predecessor, the eternal Benjamin Netanyahu was. And by all accounts that has worked well.

He’s had two successful meetings with Joe Biden and met twice with Vladimir Putin as well, the second of those meetings, a surprising flight to Moscow after the invasion of Ukraine began, was made in the hope of brokering a ceasefire between the two countries. He charmed world leaders with ‘green tech’ ideas at the environment summit in Glasgow and went on historic visits, the first official ones by an Israeli prime minister, to the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain. But the rarified summit caused him to forget that back home in Jerusalem, he’s still the leader of Yamina, a small and crumbling right-wing party, whose members are finding it difficult to get used to life in a coalition together with left-wingers and Islamists.

The government hasn’t fallen yet – it can limp on without a majority for a while at least

By joining the coalition and providing it with the necessary votes to finally oust Netanyahu, Bennett won the jet-setting job and with it all the trappings of power, including an isolating cocoon of security. His party colleagues were left to deal with Yamina’s voters, mainly right-wing and religious, at least a significant proportion of whom regarded the party’s participation in the coalition as an unjustifiable breaking of election promises. It wasn’t just their own voters. Netanyahu’s political machine, along with powerful rabbis and nationalist leaders, kept up the heat. The Yamina MPs were heckled and hounded for ‘betraying the Jewish people’, wherever they went online and in their faces, from Knesset committee rooms to their own homes and synagogues.