-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Starmer is finally getting the hang of PMQs

No prime minister since Tony Blair enjoys being in power as much as Boris. The notion that he might be kicked out by a nameless gang of cabinet lightweights is fanciful. But it makes for grabby headlines.

Labour’s Sir Keir Starmer can sense that his star is on the rise. And he’s improving. At PMQs he asked shorter questions and delivered a couple of nifty satirical thrusts that inspired his MPs. Early on, he tilted his head towards the Tory benches which were better attended than last Wednesday.

‘I see they’ve turned up this week.’ Cue howls of mirth from Labour. Moments later, he lobbed this banger at Boris. ‘I think he’s lost his place in his notes again.’ Another wave of laughter surged across the chamber.

Sir Keir has never shown such adroitness at the despatch-box. Too often he plays the know-all or the forensic anorak who memorises every detail of his brief beforehand. It never works. Nor does his habit of shaking his head and using a dearie-me-prime-minister tone. His instinct is to scold Boris like a staff-nurse catching a patient smoking a Woodbine on the fire-escape. But voters don’t like petulance or nagging. Today, he seemed more relaxed, more immersed in the sweat and dust of the ring.

Sir Keir has never shown such adroitness at the despatch-box

The substance of their debate was the forced sale of homes to pay for ‘social care.’ That innocuous phrase is a euphemism for ‘packing granny off to a home instead of letting her age gracefully in the bosom of the family.’

Sir Keir alleged that the Tories will force free-holders to flog their homes to cover the costs of care. No, they won’t, said Boris. Yes, they will, said Sir Keir. They circled the question, repeatedly accusing each other of wilful misinterpretation.

Sir Keir span it as a class-war issue and accused Boris of robbing the workers to shore up the assets of millionaires. Not at all, said Boris, with theatrical condescension. He suggested that Sir Keir was, perhaps, a bit thick.

‘I will try for the third time to clear this up in the befuddled mind of the Rt. Hon gentleman’.

The Tories, he explained are tackling a policy gap that Labour failed to plug when they were in office. ‘It’s left over from the Attlee government!’ Then he changed the subject to embarrass Sir Keir.

‘I was in a state of complete innocence about this,’ he said, his face broadening into a feline smirk. ‘I discover that he campaigned against HS2 – and said it would be ‘devastating’.’

Boris has recovered from Monday’s Peppa-shambles. He needed to show ‘grip’ today and he succeeded. It was a rowdy, enjoyable score-draw. Neither man stumbled. Neither landed a killer-blow.

The SNP’s Ian Blackford delivered his weekly impersonation of a Tory-bashing machine designed by a robot. He invoked Tory sleaze, Tory tax-hikes and Tory broken promises. Tory this, Tory that. The Hebridean Humpty never causes the PM any trouble because he never focuses on a solitary issue. Instead he mounts the pulpit and rambles through a toxic screed whose sour flavour makes him seem haughty.

Sir Keir had the best moment. Leaning across the despatch-box, with a smile of fake concern, he said,

‘Is everything OK, Prime Minister?’

It was Napoleon who warned his generals not to fight the same enemy too many times, ‘or you will teach him all your art of war.’ Slow-learning Sir Keir is adopting the tactics of his opponent. At last he’s realised that PMQs is street-theatre and not a theological disputation in the Vatican library. He’s getting it. Boris should be worried.

The rise of the neoclassical reactionaries

A strange new ideology has been growing over the last few years, you might have noticed — amid the day-to-day chaos — the slow, proto-planet-like formation. Currently, it has no name, nor an obvious leader. Its many thousands of proponents do not even seem, yet, to consider each other fellow-travellers. But to the onlooker, they’re clearly marching the same steps to the same tune. We might call it neoclassical reactionism.

The central refrain is a familiar one: the modern world is ugly, decadent, sick. But rather than seeking refuge in religion or racial politics, neoclassical reactionaries hark back to Ancient Greece and Rome — in particular, to supposedly lost values like vitality, beauty and strength. They’re obsessed with bodybuilding and Latin. They’re also obsessed, less predictably, with cryptocurrency, considering it a long-awaited way to bypass the sclerosis of centralised economies. The whole thing is sort of Nietzsche meets Bitcoin.

Up to now, the movement has been confined largely to anonymous social media accounts (albeit some with hundreds of thousands of followers). But there are early signs of a spillover into the real world. Last month, a group called Praxis announced its ambition to create the world’s first ‘city-cryptostate’, an entirely new city, constructed ‘somewhere on the Mediterranean’, founded on the shared value of ‘vitality’ — ‘the defining value of the coming epoch’.

The group’s introductory statement reads like neoclassical reactionary bingo. Our civilisation, they write, ‘is unwell’ — we ‘eat food that kills us, we’ve lost sight of beauty, and we neglect our spiritual lives’. Modern humans now ‘live within’ their screens.

Clearly, something is afoot. But what, exactly? Is this the post-religious right finally breaking free of Christianity?

All of this is a betrayal of our true potential. We, after all, ‘are descended from the people who built Rome and Athens, who dared to split atoms and voyage to the Moon’. Fortunately, thanks to crypto, we now have ‘a radical opportunity’ to unshackle ourselves from ‘the institutions that seek to limit our growth’ and achieve ‘a more vital future for humanity’.

The plan, evidently, is to attract followers online, form a kind of virtual polis in the cloud, and then to approach actual governments in the Mediterranean (apparently early negotiations have already begun) with the offer of a new physical city — funded by selling off monuments and land as NFTs. It’s not a million miles away from Peter Thiel’s concept of Seasteading: autonomous, libertarian communities built on floating platforms in regulation-free international waters. Praxis will presumably have to abide by the laws of whichever state takes them in, though it might be that the promise of thousands of good-looking, remote-working techies with six-packs encourages governments to consider tax breaks.

Which brings us to one of the oddest things about the movement. Unlike the alt-right, which was associated with disaffected, cynical incels, many neoclassical reactionaries (or at least those drawn to Praxis) appear to be young, glamorous idealists. It’s as though smoothie-detox social media influencers suddenly discovered the Dark Enlightenment (one Praxis member, a bodybuilder and ‘physical spiritualist’ called Sol Brah, recently posted to his 50,000 Instagram followers a selection of inspirational Nietzsche quotes).

Praxis’s own Twitter feed is surreal. There’s the video of the topless crypto bro doing overhead presses with a Sisyphean-sized rock. There are mock-up pictures of statues as big as the Eiffel Tower of stacked, semi-naked warriors. There are a lot of videos of guys walking around barefoot (for some reason, shoes are considered, to quote one post, ‘a symptom of civilisational collapse’). But perhaps most bizarrely, there’s a lot of hype — and not from nobodies. There are endorsements from, among others, the venture capitalists Masha Drokova and Geoff Lewis, the CEO of Replit Amjad Masad, and crypto guru Balaji Srinivasan.

If Praxis is the ‘respectable’ face of neoclassical reactionism, other — arguably more influential — figures in the movement tack much closer to the alt-right. Take Bronze Age Pervert, an anonymous writer and cult figure, whose self-published book, Bronze Age Mindset, immediately shot into the top 150 list on Amazon back in 2018.

BAP, as he’s usually known, combines Ancient Greek mythology with deliberately outrageous, ‘post-ironic’ racist and sexist generalisations. Prior to his ban earlier this summer, BAP boasted over 70,000 followers on Twitter and inspired scores of offshoot accounts (like, for instance, Latino Bodybuilders for Hellenism). His writing has drawn the attention of, among others, former Trump advisor Michael Anton, who, in a review of Bronze Age Mindset, concluded: ‘In the spiritual war for the hearts and minds of the disaffected youth on the right, conservatism is losing. BAPism is winning.’

Consider also the Passage Prize art contest, established by another right-wing Twitter celeb, L0m3z. Its mission statement rails against our ‘regime of shrill Human Resource mediocrities’, and encourages artists instead to tap into ‘powerful energies latent in the graves of pre-history, waiting for a hand, a mind, an imagination to retrieve and transform them into the creative spirit that will light a new way forward’.

The prize, which will dish out the equivalent of $20,000 in cryptocurrency, is to be judged by the ‘neoreactionary’ intellectual Curtis Yarvin and yet another anonymous Twitter megastar, Zero HP Lovecraft, whose recent book, self-published using the Bitcoin publisher Canonic, supposedly made over $50,000 in the first few hours of release.

Another website still, IM-1776, has published a number of pieces of a broadly neoclassical reactionary bent, including the Arts & Literature for Dissidents series (the first essay of which is penned by ‘Aeneas Tacticus Minor’) and the ‘D’Annunzio, Nietzsche and Bronze Age Pervert’ symposium (Benjamin Roberts’s opening essay champions nightclubs as outposts for Nietzschean, ‘hard-right’ vitality).

Clearly, something is afoot. But what, exactly? Is this the post-religious right finally breaking free of Christianity and setting the civilisational agenda for the next thousand years, or is it a group of naive techies ushering an ideological Bitcoin bubble? Is it a renaissance or the beginnings of crypto-fascism? Perhaps, in true Nietzschean style, we shouldn’t spend too long staring into the abyss.

Has Gary Neville taken his eye off the ball?

‘Enough’, said Gary Neville this week as he (once again) attacked Boris Johnson. The ex-footballer is no stranger to attacking the Tories: in the past few months, the former England right-back has dubbed Johnson a ‘liar’, bizarrely suggested that the PM is a ‘spaghetti bolognese of a man’ and accused the Government of ‘incompetency’.

Neville is clearly a busy man: as well as his day job talking about football, he is listed as a director for 56 firms

Even football fans aren’t safe from Neville’s bit-part political punditry. During England’s Euro 2020 semi-final win this summer, when the whole country was (briefly) united for once, he interjected to suggest that Gareth Southgate, the England manager, had shown more leadership than the Prime Minister. But while Neville’s career as a Tory attack dog appears to be taking off, is he in danger of taking his eye off the ball elsewhere?

Mr S only asks because one of the many, many companies which list Neville as a director has failed to file its accounts on time. As a result, the curiously-named ‘The man behind the curtain (Leeds) limited’ could soon be struck off as it passed its deadline at the end of September to file its accounts for the previous year. The firm lists Neville as one of two directors alongside chef Michael O’Hare, who runs Leeds’ only Michelin-starred restaurant under the same name.

Neville is clearly a busy man: as well as his day job talking about football, he is listed as a director for 56 firms. Some are involved in hotels, developing building projects, education and management consultancy. Not all these firms remain active, but even so, having dozens of business interests is surely enough to keep Neville’s hands full.

Perhaps it is time for Neville to take a break from burnishing his comradely credentials to get his own house in order?

Germany’s new coalition is a recipe for stagnation

A new, fresh leader. Bold radical ideas. And a programme for rebooting an economy that, for all its formidable strengths, is, to put it kindly, a little stuck in the 20th century. Later today, Germany is set to anoint its first new Chancellor in 15 years, and, at the very least, you might expect some new ideas. The trouble is, there is little sign of them from Olaf Scholz. Instead, the country is opting for the euro-zone’s slow lane, falling behind a rapidly reforming Italy and France.

After two months of complex negotiations, following an inconclusive election in September, the Social Democrat leader Olaf Scholz will finally present his coalition agreement later today. He has put together an unlikely grouping of the Social Democrats, a lumbering left-of-centre, trade union party with a rising Corbynista wing, the Greens, and the pro-business, pro-market Free Democrats.

The dynamics of the European bloc are in a rare state of flux

In reality, none of them really agree on anything very much except that they think it is about time they had a go at running a ministry or two. The platform for government is likely to be a bland mix of infrastructure spending, phasing out coal power, and slightly easing the debt brake that limits the ability of any German government to borrow money. Here’s the problem, however: the new government is bad news for Germany.

The dynamics of the European bloc are in a rare state of flux. Under Mario Draghi, Italy has embarked for the first time in a generation on serious reforms. It has also skilfully negotiated the lion’s share of the European Union’s Coronavirus Rescue Fund, allowing it to turbo-charge its economy with lots of money borrowed from other people. The result? Italy is forecast by the IMF to expand by 5.8 per cent this year.

Across the border, France’s president Macron gets plenty of flak, not least in the UK, and his record as a reformer has been tepid, to put it mildly. And yet he has managed to inject some entrepreneurial vigour into the French economy, and spent lavishly enough to keep demand growing. The IMF forecasts it will grow by more than six per cent this year.

But Germany? With a declining auto industry, which accounts for ten per cent of total GDP, few digital start-ups, and a reliance on exports to China, it is only forecast to grow by 3.1 per cent as it struggles to recover from the pandemic. With a fresh lockdown looming, it may not even reach that.

We are used to the cliche that Germany is the euro-zone’s strongman, with the mightiest economy, easily outpacing the crisis-prone South. And yet that view is increasingly out-of-date. Germany is in danger of turning into the weakest major economy in the bloc; as that happens, power will inevitably shift from Berlin to Paris and Rome.

Sooner or later, Germans will vote for a Chancellor who will reform the economy, and get the economy moving again. But it won’t be Scholz, and it won’t be the fractious coalition he unveils today. It will condemn the country to the slow lane.

PMQs: Johnson’s shtick isn’t working

Sir Keir Starmer enjoyed himself again at Prime Minister’s Questions today. He came armed with plenty of very good lines, and of course had more than enough government messes with which to poke Boris Johnson. The Prime Minister, for his part, had more fire in his belly than last week, presumably because he’s managed to get rid of his cold. But he didn’t manage to rescue his authority after a very tricky three weeks.

The Prime Minister, for his part, had more fire in his belly than last week

The Labour leader focused most of his questions on the social care revolt this week, asking Johnson why he had promised that no-one would have to sell their home when that has turned out not to be the case. The Prime Minister replied with the careful formulation of words that he’s been using to claim that he isn’t breaking that promise after all: he insisted to the Commons that ‘if you and your spouse are living in your home’, then the government will not count it as an asset for the means test. That is quite different to ‘no-one’ having to sell their home and is another illustration of Johnson’s tendency to create a mess by promising the impossible.

Starmer argued Johnson had ‘just described the broken system he says he is fixing’, then joked that Tory MPs, who were very noisy in this session, had turned up this week. He then asked whether, if this Prime Minister made it to the next election, anyone could take his promises seriously, before describing the Downing Street approach to reform as being ‘a Covent Garden pickpocketing operation’, with Johnson charming people while the Chancellor took away their money. But people were beginning to worry that the operation wasn’t working so well anymore, he said, asking the most memorable line of the session: ‘Is everything OK, Prime Minister?’

Johnson retorted that this line of attack wasn’t working, resorting once again to his Captain Hindsight keeping everyone in lockdown line that he tends to use when he’s struggling a bit. He didn’t leave the session with more problems. But the comparison between the spontaneous and noisy laughter at Starmer’s lines and the orchestrated defensive noises coming from the Tory benches told its own story: Johnson’s normal shtick isn’t working either.

Fact check: are the Tories cutting taxes?

Ping! No, not the dreaded Covid app but rather another beseeching email from CCHQ, begging money for Tory funds. Reading through the party-politicking, Mr S was curious to see that among the party’s list of achievements was the claim that ‘we’re delivering what the British people voted for’ by ‘cutting taxes for hardworking people.’

An intriguing boast, given that Rishi Sunak is hiking National Insurance, which applies to all employees including those on minimum wage, by an effective 2.5 per cent – despite the Conservative Party’s pledge in 2019 that ‘we will not raise the rate of income tax, VAT or National Insurance.’ Corporation tax has been raised to 25 per cent from 2023 while Air Passenger Duty on long-haul flights was increased in last month’s Budget.

The personal income tax allowance has been frozen while the cut in the taper rate for Universal Credit applies to just a tiny subset of people on benefits. Unsurprisingly, when Steerpike asked CCHQ for any evidence or supporting statement to the claim that the party had cut taxes, no answer was henceforth coming.

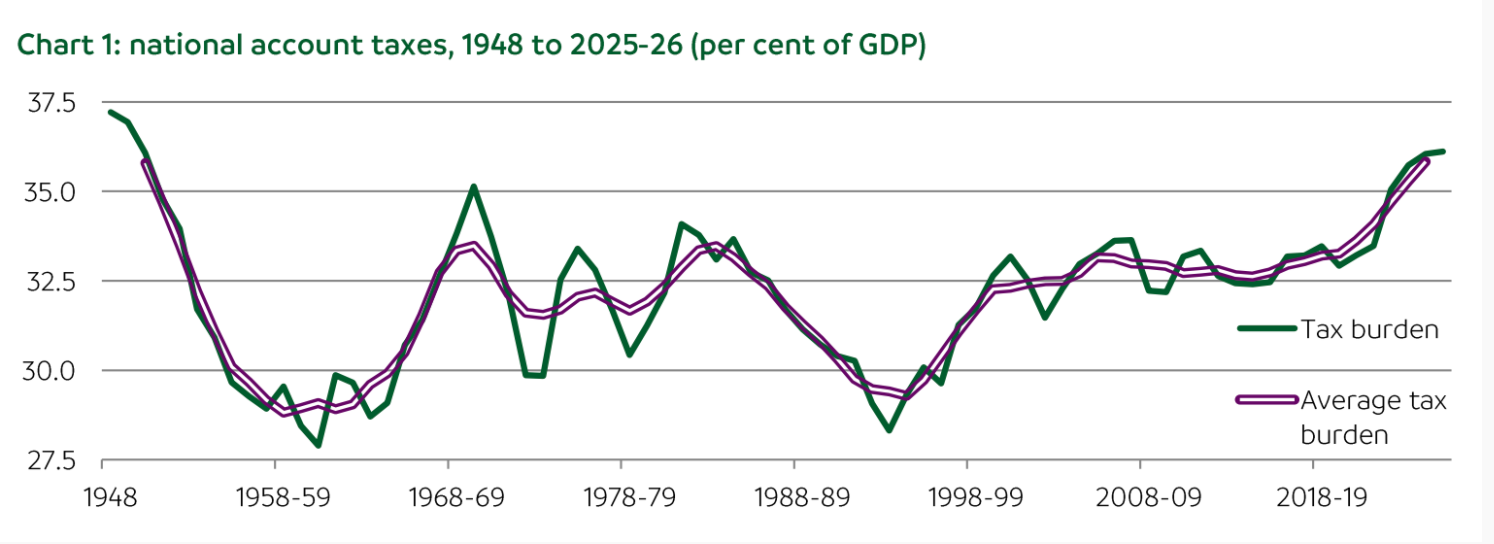

For as research by the Taxpayers’ Alliance (TPA) helpfully points out, following Rishi Sunak’s most recent Budget the tax burden is now scheduled to reach a 73 year-high, with the level of taxation as a percentage of GDP under Boris Johnson now higher than it has been since the days of Clement Attlee’s post-war siege economy.

Danielle Boxall of the TPA told Mr S: ‘CCHQ must be living in a different world if that’s what they call tax cuts. By the time of the next election, the sustained tax burden is set to be the highest it’s been since the country was recovering from the Second World War.’ She added that since the party came to power under David Cameron in 2010 there were more than 1,000 tax rises in 10 years.

As an aside, it’s worth remembering what the British people actually voted for in 2019. According to the party’s manifesto, the Tories pledged to ‘proudly maintain our commitment to spend 0.7 per cent of GNI on development’ (they didn’t), ‘keep the triple lock’ (they didn’t) and build the ‘Northern Powerhouse Rail between Leeds and Manchester’ (they won’t).

And when Boris Johnson launched the manifesto he claimed ‘We will not be cutting our armed services in any form. We will be maintaining the size of our armed services’ – something contradicted in March when Ben Wallace, the Defence Secretary, confirmed the Army will be shrunk by a further 10,000 troops.

Still, perhaps all that wouldn’t fit into a pithy party-fundraising email eh?

Sadiq surrenders on face masks

Throughout the pandemic, Sadiq Khan has been positively evangelical on face-coverings. The Mayor of London has waxed lyrical about their virtues throughout the pandemic, declaring that: ‘my mask protects you, your mask protects me’ that ‘if we don’t wear masks, the virus will spread further’ and calling such face-coverings ‘the most unselfish thing you can do.’ Ahead of Boris Johnson’s July 19 unlocking, Khan attacked his decision to axe the legal requirement to wear a face covering on public transport.

Instead the Mayor insisted that wearing a mask remained ‘a condition of carriage’ for passengers using public transport in London, with some 500 enforcement officers patrolling the capital’s trains and buses to eject the unmasked. But has the Mayor of London now effectively given up on enforcement of his rules? For figures unearthed by Steerpike suggest that your chances of being denied entry on the Tube for not wearing a mask are not even one a million – it’s actually half as high as that.

A Freedom of Information request by Mr S to Transport for London (TfL), whose board is chaired by Khan, has revealed that just 121 people were refused entry on the Tube in four months between July and October 2021 – compared to a figure 100 times that for the previous 11 months. TfL had previously boasted that between the introduction of face coverings on the Tube in June 2020 and the end of May 2021, some 12,176 were refused travel – the equivalent of more than 1,100 a month.

But now that monthly figure of Tube refusals has dropped to just 30, meaning that on average only one passenger a day is refused entry despite the total of daily journeys on the underground network surpassing the two million mark. Last month just 13 passengers were refused entry in 31 days.

The lack of any kind of enforcement would suggest the tough talk on face coverings is merely another example of Covid pantomime. With the rhetoric being so very different from the reality, TfL risks putting the ‘mask’ into ‘masquerade.’

2531: Villainy – solution

The unclued lights are VILLAINS encountered by James Bond.

First prize Ian Skillen, Cambuslang, Glasgow

Runners-up Liz Knights, Walton Highway, Cambs; Keith Williams, Kings Worthy, Winchester, Hants

Boris Johnson is having a bad week

Tory MPs had hoped this would be the week that Boris Johnson turned the tide after a tricky three weeks of Tory sleaze allegations and discontent on the backbenches. It’s not going quite to plan. After an odd speech to the CBI conference on Monday and a narrow win in the Commons on the government’s social care amendment, the papers carry reports that MPs have started sending letters of no confidence to the 1922 committee.

The Sun quotes an MP comparing Johnson to soup:

‘He is like José Mourinho — he was good a decade ago and his powers have been fading ever since. Yes he won an election, but a bowl of soup could have beaten Jeremy Corbyn. There is real anger. He has until spring to get back on track or he will be in real trouble. Letters have gone in. I am on the cusp myself.’

10 Downing Street seems set on starting a war with the neighbours in No. 11

Meanwhile, 10 Downing Street seems set on starting a war with the neighbours in No. 11 – blaming the Treasury (which they deny) for giving a quote to the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg in which a Downing Street source was withering about the Prime Minister. The issue for Johnson is that in truth this is one of many quotes from aides and ministers in the press in recent weeks criticising his performance.

There is a conscious effort by ministers out on the broadcast round to defend the Prime Minister, with Dominic Raab this morning describing him as ‘Tiggerish’. But ultimately if Johnson and his team want to move past this row a good place to begin would be by not fanning the flames any more. Any blame game for recent errors – whether that’s frustration at the whips, Rishi Sunak or even No. 10 colleagues – only guarantees that the story will keep going.

MPs feeling little loyalty towards the Prime Minister right now hope that Johnson can draw a line under recent events and find something else to talk about. Today’s performance at Prime Minister’s Questions is viewed as more important than most – given it could confirm his CBI speech was just a blip. As one minister puts it: ‘We need a few wins between now and Christmas in order to steady the ship.’

What Bitcoin’s crypto critics get wrong

What’s the truth about Bitcoin? Critics couldn’t be clearer: it’s a fad that can’t decide whether it’s a currency or a speculative investment. ‘You’re betting, essentially, on being the last person holding the bomb before it goes off,’ wrote Sam Leith on Coffee House. Many others agree. But Bitcoin’s critics are wrong: there’s nothing faddish about it. Bitcoin is a monetary revolution and is here to stay.

Perhaps it’s no surprise that Bitcoin has attracted its sceptics. Understanding what it’s about isn’t easy. In short, Bitcoin is a monetary network, an incorruptible ledger, with the money supply fixed by code (there will only ever be 21 million Bitcoin). It allows anyone with an internet connection to engage in a transaction that cannot be altered or stopped, with currency that cannot be seized, all without requiring a middleman such as a bank. The good news is that this means it can’t be manipulated by governments or central banks.

It’s no surprise that Bitcoin has attracted its sceptics

The typical journey for someone describing themselves as a ‘Bitcoiner’ is that they ‘came for the price action, but stayed for the revolution’. After this, defending Bitcoin becomes akin to defending the invention of the wheel. When they understand the benefits of sound money it shifts their outlook on capital accumulation and protection.

The best evidence that Bitcoin captures people’s imaginations can be seen in how widely it’s been adopted. Around 1.5 per cent of the world’s population are estimated to own some amount of Bitcoin, and a lot of those people have held (referred to as ‘hodled’) Bitcoin for a good period of time. The result is that this asset, which was worthless 12 years ago, has a current market cap in excess of $1.2 trillion (£900 billion). Bitcoin is currently jockeying for position as the 13th biggest currency behind the Swiss Franc, which has long been considered to be the most stable currency in the global economy. Who knows where it will rank in the future.

But either way, Bitcoin has become harder and harder to dismiss. This is because it ticks more boxes than any other previous asset. As a store of value it has all the attributes of traditional physical assets like gold: it is scarce, durable, and fungible. However, it also improves on gold: it is divisible, portable, and can’t be confiscated. This means that Bitcoin attracts those looking for protection: whether it’s people worried about hyperinflation or authoritarian policies, or large institutions looking to hedge against inflation. Even countries that are pegged to the US dollar, and subject to its loose monetary policy, can see the upside.

Bitcoin is more than just an online asset though; it is designed to be used in much the same way as ‘real money’. Bitcoin enables secure real-time payment from anywhere to anywhere. Transactions typically settle in ten minutes, and, with new tools like the lightning network, users can send and receive Bitcoin almost instantly and at little cost. Already retailers are catching on: in El Salvador which recently passed its Bitcoin law, it is being accepted in well-known businesses such as McDonalds, Starbucks and Pizza Hut.

So why are some still so keen to trash Bitcoin? Politicians and regulators say crypto facilitates criminality. Its environmental credentials have been widely condemned. Traditional economists state it is too volatile and has no intrinsic value. The truth is that some of its critics feel threatened by a currency they can’t control.

The inability to print new Bitcoin demonetises the political class by allowing the electorate to choose an alternative currency to store their wealth; while Bitcoin’s proof of work consensus mechanism empowers the productive class. This is what better money does, it takes out the people who are just rent-seeking in our political structure, replacing them with leaders promoting sound economic policy. We are seeing this in the US where government debt is spiralling out of control and a new class of congressmen is making Bitcoin part of their agenda.

In a time of rampant inflation and a widening wealth gap, Bitcoin has become the lifeboat for many. Where Richard Nixon took the US off the gold standard in 1971 to print money to finance the Vietnam war, an army of Bitcoiners is creating a new standard, a Bitcoin standard, as Nic Carter called it ‘a most peaceful revolution’.

Liz Kendall to be first MP to have a child through surrogacy

Labour frontbencher Liz Kendall is expecting a baby through a surrogate, making her the first MP to have a child through surrogacy.

Kendall tells me that she and her partner are expecting the baby in January after a lengthy and painful fertility battle. She says: ‘We have been through a lot to get here but it really is happening now, and we’ve been telling people this week.’

During the couple’s attempts to conceive, Kendall suffered two miscarriages and needed surgery after both. Last month she also spoke in a parliamentary debate about the ‘debilitating’ symptoms of the menopause that she had been experiencing over the past year. She won praise for telling MPs about the ‘truly terrifying sense of anxiety and panic that I had never experienced before’, exhaustion, hair loss and mornings where, after struggling to sleep at all, she would find herself thinking: ‘How on earth am I going to make it through the day?’

In 2013, Labour peer Oona King had a baby through a surrogate, while Kendall is the first MP to do so. She is fiercely private and rarely discusses her personal life with colleagues, let alone in public: indeed, she has insisted on keeping most of the details beyond the basic facts of this good news private too.

She will take maternity leave from the Labour frontbench and as an MP when the baby arrives.

Even Boris’s supporters are turning against him

Perhaps the past seven chaotic weeks are best regarded as an experiment by the Tories. Boris Johnson’s intention appears to be to establish just how badly he can run the country while remaining on course for re-election.

Despite calamity after calamity hitting Boris’s administration, things are still looking rosy for the party: Politico‘s poll of polls shows that we are basically back where we were this time last year – at pretty much level-pegging between the Conservatives and Labour. There is no sign of the kind of positive surge in support for the opposition that would indicate the electorate is considering putting it into power.

A year ago – on 24 November, 2020 – Politico’s poll of polls had the Conservatives on 39 per cent and Labour on 38 per cent. As of this week, those averages were Conservatives at 37 per cent, and Labour at 37 per cent.

And yet something significant really is happening, as is revealed when looking at the Prime Minister’s personal poll ratings. His YouGov monthly tracker has deteriorated for seven successive months. His net score now stands at -35, which is even worse than Keir Starmer’s. The percentage of people saying Johnson is doing badly has hit an all-time high of 64 per cent too. We have entered territory where it is no longer just the people who dislike Johnson saying he is doing badly; lots of his 2019 coalition of voters appear to be reaching the conclusion that he is fundamentally useless too.

Johnson would have been better not to talk to business leaders at all than to deliver the drivel he came out with.

It has long been my conviction that Starmer is a duffer who cannot win the next election. But equally, should the Downing Street operation not improve soon, there is every chance that Johnson will be sent on his way by his own side.

If we look at the major developments since Tory conference, we can see that Team Johnson has blundered in every case. It may be that Cabinet Secretary Simon Case and Downing Street chief-of-staff Dan Rosenfield are both capable performers in general. But it is transparently obvious that neither has the political nous or clout needed to keep on track a man depicted by his former chief adviser Dominic Cummings as a wonky shopping trolley.

The most telling errors since conference can neatly be categorised as Downing Street’s ‘seven deadly spins’. The Owen Paterson disaster is the one that has garnered the most coverage. Many observers saw in advance that succumbing to a plot by various country house Tories to get their mate off the hook was bound to blow up in Johnson’s face. But apparently nobody with any authority within the inner-circle expressed that view forcefully. And so the PM drove the car into a ditch.

Going gaga over Green stuff for COP26 was also bound to intensely irritate a substantial portion of the core Tory vote. A wise strategist would have ensured there was a simultaneous balancing offer on another big subject from the PM to cheer up these voters. But nobody did.

The third big mistake came from the PM himself in the wake of the shocking killing of Sir David Amess – repeated after the Liverpool terror plot – in the form of his complacent and cliched responses (‘We will never allow those who commit acts of evil to triumph’, ‘The British people will never be cowed by terrorism’ etc) that were unaccompanied by any meaningful plan to tackle the threat of Islamic extremism. Platitudes in the face of the Islamist onslaught may once have sufficed, but no longer.

Mistake four came in the mishandling of the changes to the northern rail strategy announced last week. Nobody ‘rolled the pitch’ in advance or sought to win the argument for switching from a couple of prestige investments to a more broadly-based strategy for medium-sized, swiftly deliverable schemes. So spending more than £90bn on northern rail improvements somehow became seen as a slap in the face for Red Wall voters by snooty southern Tories.

This has since been compounded by mistake number five: tweaks to the funding rules for social care support that appear to protect owners of high-priced houses in the south much better than low-priced ones in the north. It beggars belief that nobody in Downing Street spotted the potential for this narrative to get going and that such a delicate and dangerous political issue should have been allowed to get taken over by Treasury bean-counters.

The sixth deadly spin came with the PM’s under-prepared and badly delivered speech to the CBI this week. If David Cameron was at times the ‘essay crisis’ premier, at least he usually ended up submitting work of a decent standard even if it was after frantic, last-minute effort. Johnson would have been better not to talk to business leaders at all than to deliver the drivel he came out with.

But it is the seventh deadly spin that has the capacity to do the most damage: Boris’s complete failure to put together a workable plan to tackle the cross-Channel boats. On Johnson’s watch, we have seen two annual treblings of these illegal arrivals, despite his pledge on taking office in summer 2019 that: ‘We will send you back’. If the traffic trebles again next year it will mean up to 90,000 walking up south coast beaches to lodge asylum claims.

So why has Johnson allowed Priti Patel repeatedly to over-promise and under-deliver? Why has he not requested and acted on a clear assessment of where an offshore processing centre could be situated so the pull factor can be eliminated? What about a deserted British overseas territory such as South Georgia, or Lafonia at the southern end of East Falkland? Why has he not established which international conventions the UK would need to withdraw from to implement offshore processing or told voters if he is ready to do this? Why is he allowing the Nationality and Borders Bill to languish in the slow lane of legislation?

The lack of seriousness or political will is surely down to Johnson and Johnson alone. Tory voters and Leave voters have rumbled it and hate it. We cannot go on like this much longer.

Why I’ve embraced Lanzarote’s sci-fi vibe

I never realised Lanzarote was such a weird place. During an extended Camino de Santiago pilgrimage to escape UK lockdowns, various pilgrims I met urged me to visit the splendours of the Canary Islands as a natural sequel to the splendours of the Iberian Peninsula we traversed. But Lanzarote was rarely mentioned.

As soon as you land at the north easternmost of the eight main Canary Islands you quickly appreciate there’s much more to it than cheap bars, piña coladas and the often-derided Brits Abroad vibe. Looming over the airport—whose runway must be a contender for one of the world’s greatest, though more of that later—is a landscape of volcanic mountains that looks like a cross between the surface of the Moon and Mars. While stretching away to the horizon is the vast expanse of the Atlantic Ocean. It’s a striking mix, as is the whole composition of this small 845-square-kilometre island, lying only 80 miles off the Moroccan coast, and formed—like all the Canary Islands—by volcanic eruptions millions of years ago.

This Remembrance Sunday, by way of distraction, I struck out toward one of those distant peaks. Ascending a ridgeline, I could see in the distance on the western side of the island the emerald-green waters of the Laguna y Salinas de Janubio. Created by those volcanic eruptions, which formed a barrier of lava between the lagoon and the sea, since 1895 its waters have been evaporated in the adjacent salt pans. The geometric pattern of the pans and their different colours—depending on the amount of water in each—stand out like an enormous work of art or strange totem, as do the adjacent rows of cone-shaped salt piles, brilliant white in the sun.

At the summit, surrounded by a bundle of masts and satellites belonging to the island’s communications systems, I gazed down at Playa Blanca at the southern tip of the island, its bars, restaurants and resorts a British bastion for many of those holidaymakers arriving at the airport. The day before I’d mingled down there with my people, striking as ever when let loose on foreign shores and no less beefy or less prone to go lobster red in the sun after continuous lockdowns. As I descended, the softer light of the sun setting behind me turned the dirt I was walking along a burnt orange, while the moon already stood out vividly to my front. Dotted around were multi-coloured cacti straight from an Aldous Huxley psychedelic vision. It felt like I had been transported to the landscape of the new Dune film. Set against the frolics that most holiday makers come for, it all contributed to a strange sense of the superfluous and hedonistic mixed with the grandiose timelessness of nature and the cosmos.

Despite the island’s interstellar exploratory qualities, my favourite spot turned out to be right where I had arrived. Between the start of the airport’s runway and the ocean is about 50 metres of beach. People gather there to watch the jets emerging from the cloudless sky in the distance above the sea. ‘We can’t stop coming back here to watch it all,’ commented a British lady looking out toward the sea like I and the others there. Seen from afar, the aircraft’s external lights look like a car’s headlights emerging serenely from the azure blue before the jet screams in right above your head thrown back just before the screech of tires landing.

Once the sun has set, those same ‘headlights’ cast a moon-like corridor of reflection on the sea’s tremulous surface as each aircraft approaches. Perhaps the five-euro bottle of tasty El Coto Rioja Crianza wedged in the sand beside me had something to do with it, but not since the sight of a C-130 Hercules transport plane approaching to land in Iraq has the sight of aircraft making their landing and take-off manoeuvres filled me with such jubilation. Ryan Air! Easy Jet! Vueling! Jet2! Never have the names and logos of lost-cost airlines appeared as such talismans of freedom and adventure, after nearly two years of travel restrictions. And now, on top of that, increasingly there appears a big wagging finger from our rulers aimed at our irresponsible Carbon-emitting lives, indulging in such outlandish demands as holiday flights to sunnier climes for respite with loved ones.

But is jet travel all bad when it can plant you in a matter of hours into such otherworldly landscapes? Pope Benedict XVI captured the dichotomy during his famous 2006 ‘Regensburg Address’ to various representatives of science: ‘The positive aspects of modernity are to be acknowledged unreservedly: we are grateful for the marvellous possibilities that is has opened up for mankind and for the progress in humanity that has been granted to us.’

One day the runways—or more likely launchpads—may be taking future generations of holiday makers to truly more Martian climes. I hope so. For now, though, we have the lunar landscape of Lanzarote to spark our imaginations. Furthermore, it’s eastern-most position in the archipelago makes it a great launchpad for exploring the constellation of islands strung out westward. Fuerteventura is a short ferry ride from Playa Blanca and to its west lies Gran Canaria, while Tenerife is the next along and so on—each volcanic island offering their own marvellous variations on the Martian theme.

Fears over Mandarin shortage in Whitehall

‘China Spy Blitz’ blared the Sun this morning: ‘UK spooks hiring Mandarin speakers in cyber war.’ Spy bosses, the paper reports, are embarking on a recruitment drive, directed at people who speak the language or have grown up within a multilingual family, with MI5, MI6 and GCHQ all increasingly wary about a moment of reckoning with the Communist superpower. Yet while the secret services have woken up to the threat posed by Beijing, others within government appear to still be fast asleep.

Newly obtained figures reveal that the number of fluent Mandarin speakers within the Foreign Office (FCDO) has dropped by nearly 10 per cent since 2016. A Freedom of Information request by Mr Steerpike showed that 41 British diplomats hold the ‘gold standard’ certification in Mandarin, known as C1, down from 45 over the past five years. Such figures refer only to the number who have passed the C1 exam and do not reflect the number of total staff who speak some level of Mandarin within the department. C1 exams are valid for five years, with diplomats then expected to re-qualify.

Since the summer of 2016 – when David Cameron was heralding a new UK-China ‘golden era’ – relations between the two countries have deteriorated rapidly over Beijing’s atrocities in Xinjiang, the subjugation of Hong Kong and the handling of the Covid pandemic. Yet despite the government admitting in its landmark defence paper in March that China is the ‘biggest state-based threat’ to the UK’s economic security and presents a ‘systemic challenge’ to Britain, there are cross-party concerns within Parliament that the Foreign Office is not moving quickly enough to improve Chinese language skills within the UK’s diplomatic corps.

Alicia Kearns, Conservative MP and a member of the Foreign Affairs Select Committee told Mr S: ‘If we’re going to get serious about understanding China, and making policy to protect our country, our values and the international order, we need mandarins who understand Mandarin.

The Foreign Office should be investing heavily in increasing its Mandarin speakers – not lackadaisically allowing a decline. There’s no chance the CCP is failing to get its diplomats skilled in foreign languages, and a failure to do so on our part is unforgivable.’

Stephen Kinnock, Labour MP and the party’s spokesman on Asia and the Pacific, added: ‘Senior officials at GCHQ are right to be concerned about China’s digital dominance, and the cyber security threat that this will pose to Western nations like Britain. Yet ministers are putting Britain’s values, national security and strategic interests up for sale in exchange for ‘strings attached’ Chinese investment. The decline in Mandarin speakers in the FCDO shows that the department is failing to prioritise the need to fully understand China’s objectives, and to respond accordingly.’

The total figure for FCDO officers with a valid C1 certification doubled between August 2011 and August 2016 from 277 to 573, a figure which has dropped slightly in the five years since, down to 558 in August 2021. And despite recent talk within UK government circles of an ‘Indo-Pacific tilt’, the number of Arabic C1-certified speakers has dropped from 55 to 43, with those fluent in Indonesian and Korean dropping from ten and seven to seven and ‘fewer than five’ respectively, with the number of Japanese speakers remaining consistent at 16. By contrast, the total of Russian speakers has risen over the same period from 28 to 44 with French retaining its crown as the language spoken by most C1 certified diplomats, up from 145 in 2016 to 161 in 2021.

And as one China expert points out to Mr S: ‘Fluency in French matters much less than Mandarin because the way China is governed is Mariana-trench deep steeped in history and connotative phrases. Slapping French into Google translate gives you a pretty good idea of what’s going on. Doing the same with Mandarin means you miss at least half the context.’

Let’s hope more mandarins brush up on their Mandarin soon.

How having babies fell out of fashion

With all of our institutions now firmly under the iron fist of progressivism it was only a matter of time before social justice mission creep slipped under the doormat and into the home. You can only promulgate the idea that we live under a tyrannical patriarchy for so long before young people take notice and begin to lose trust in the whole idea of intimate relationships with the opposite sex. Fourth wave feminism has shifted its focus from the work place to male/female relationships and a growing underclass of men is turning its back on women by joining poisonous underground groups such as INCELS and Men Going their Own Way (MGTOW).

Why would any young person choose to settle down and have kids against such a toxic backdrop? Well, increasingly they aren’t. In Bari Weiss’ recent article entitled First comes Love. Then Comes Sterilisation the writer reveals that ‘Americans are making fewer babies than we’ve made since we started keeping track in the 1930s. And some women… are not just putting off pregnancy but eliminating the possibility of it altogether.’ Last year, the number of deaths exceeded that of births in twenty five US states – up from five the year before. The marriage rate is also at an all-time low, at 6.5 marriages per 1,000 people. ‘Millennials are the first generation where a majority are unmarried (about 56 per cent).’ The number of young men (ages 18 to 30) who admit they have had no sex in the past year tripled between 2008 and 2018. ‘Cities like New York, where young, secular Americans flock to build their lives, are increasingly childless. In San Francisco, there are more dogs than children.’

Some of this will be down to lifestyle choices, of course, but there appears to be something more disturbing going on. As Weiss points out ‘the message from this young cohort is clear: Life is already exhausting enough. And the world is broken and burning. Who would want to bring new, innocent life into a criminally unequal society situated on a planet with catastrophically rising sea levels?’

I would go further and argue that young men and women are losing a sense of their shared humanity. A malign force that sees conflict as the only way to resolve perceived inequalities has captured their minds. After all the sexual abuse campaigns and anti-male rhetoric of the past few years is it any wonder the young feel less disposed towards each other? In a recent survey of 5,000 single US citizens by the dating service Match, 80 per cent said sex was less important to them now than it was before the pandemic. In the UK the 2020-21 Natsal-Covid study, which replaced the National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles, paints an equally depressing picture. Sex is seen as a minefield where one wrong move can lead to assault or a lengthy court battle over issues of consent. Why take the risk?

Of course it isn’t only women who are choosing to remain single and childless. Increasing numbers of men, both young and not so young, tell me they won’t commit out of a fear of making a bad decision and ending up with the ‘wrong’ woman. The proliferation of dating sites has made them picky and uncompromising. In many cases they’d much rather a quiet life in front of the PlayStation than, as one 36-year old put it, ‘being locked in an interminable Relationship with someone I hate’. Others told me they feared accusations of being ‘part of the toxic patriarchy’. Worryingly responsibility is seen not as a meaningful way to live but a form of enslavement. In extreme cases I heard men describe strong, opinionated women as ‘feminazis’.

Social justice activism has sown so much discord between the sexes that many women view the act of having children through an entirely political lens, as I discovered at a recent press dinner. As the only man at a table of around twenty female journalists aged between twenty-five and thirty-fiv,e much of the initial chat didn’t concern me. But when the conversation eventually turned to marriage and children, I felt I should speak up, rashly perhaps considering how outnumbered I was. What surprised me was the almost unanimous contempt for both the institution of marriage and of family life more broadly. When I argued that the evidence seemed to suggest that it was perfectly natural for women to want to marry and have kids the level of indignation seemed disproportionate. ‘It’s all the patriarchy’s fault, men have conditioned women to want kids’ seemed to be the general consensus or as one thirty-five year old put it ‘what women really want is to f*** and have a good time without the pressure to breed’.

I pointed out that men often struggle with the burden of their own biological instincts, which they immediately dismissed as ‘unacceptable, socially constructed behaviour’ driven once again by the all-pervasive patriarchy. You could argue that a group of ambitious young journalists is hardly representative of most young women but, having subsequently spoken to a cross section of thirty-something females, there appears to be broad agreement with the idea that men and women’s sexual proclivities are more a product of social construction than biological instinct.

There may be a certain amount of truth in this but the danger now as I see it is that we are socially constructing the young away from intimate relationships altogether, thereby condemning them to a life of loneliness and resentment, the consequences of which really will be catastrophic to the future of the planet.

Covid could paralyse the new German coalition

An iron curtain has descended on Europe, and once again, it goes right through the middle of Germany. The average national infection rate is currently exploding, but the real story is not the average, but the vast gap between east and west, with another gap between the north and south. The north-west of Germany is like the rest of the western EU, cases growing but not at such an alarming rate. But the south-east is like central and eastern Europe. Hospitals are overflowing. Berlin has ceased all non-emergency operations. Germany’s formidable and numerous intensive care units are now for the first time in the pandemic experiencing bottlenecks, for which they have made no emergency planning.

The politics behind this is potentially quite dangerous. Markus Söder and Winfried Kretschmann, the state premiers of Bavaria and Baden-Wuerttemberg, came out yesterday with a demand for obligatory vaccination. Angela Merkel’s spokesman said immediately that this was an issue that she would happily pass on to Olaf Scholz and his coalition. The only political parties who are dead set against compulsory vaccination are the AfD and the FDP, the latter being a member of the incoming traffic light coalition. The FDP is also opposed, as a matter of principle, to nationwide lockdowns.

It is not hard to foresee that Covid will overshadow the new coalition’s agenda and drive a wedge between the parties right from the start

It is not hard to foresee that Covid will overshadow the new coalition’s agenda and drive a wedge between the parties right from the start. Scholz can hardly fall back into grand coalition mode and stitch up legislation with the opposition CDU. However, he will need their votes for any legislative changes, including lockdown and vaccination rules. A plausible result of these interlocking dependencies is paralysis, and recriminations within the coalition, and across the political spectrum. It is not hard to see a scenario in which the only winner from this mess is the AfD, which is anti-lockdown and anti-compulsion — and in opposition.

One of the notable statistics is that vaccination rates are particularly low in the AfD strongholds of eastern Germany. Low vaccination rates are likely linked to distrust of state actors: politicians, but also health officials and scientists. Opinion polls show that the German public is divided over compulsory vaccination. A narrow majority seems to be in favour, but this number needs to be interpreted carefully. There is an effect at work similar to that of Brexit. Those who are opposed to compulsory vaccination feel more strongly about it than those in favour. You may think of compulsory vaccination as an easy way out of the crisis, but this will come at the price of solidifying support for the AfD beyond the usual anti-immigration crowd. This support may not disappear once the pandemic finally recedes.

Another political consequence is that it would cement the internal divisions of the CDU, which is split between a pro-Merkel wing, with strongholds in the suburban areas of west Germany, and a conservative wing with strongholds in rural areas across the country and through the east, in both urban and rural areas. The CDU will likely swing to the right in the upcoming leadership election. Friedrich Merz has a good chance of winning the contest against his more liberal opponents. The election is decided by members, not officials that tend to be loyal to Merkel.

A minor, but still noteworthy political consequence of recent events is that a once-promising political career has collapsed in the last few days: that of Jens Spahn, the health minister. Spahn’s ministry is responsible for two messed-up vaccination campaigns in less than a year. His latest and probably last foolish act has been to announce a temporary stop to the procurement of the domestic Pfizer jab, and to use up existing stocks of Moderna at a time when the booster campaign is failing to come off the ground. Germans are broadly pro-vaccination, but they’re less inclined to mix their jabs. There are logistical reasons that might explain this move, yet the impact it has on the sagging booster shot campaign is devastating.

This article was first published in the EuroIntelligence morning briefing. For a trial subscription click here.

What explains Germany’s vaccine scepticism?

By the end of winter, Germans will be ‘vaccinated, recovered or dead,’ according to the country’s health minister Jens Spahn. Yet as Germany battles another wave of Covid outbreaks with renewed restrictions, the outgoing Merkel administration is failing to inspire public confidence in the central government.

In the city of Dresden, which usually hosts some of Germany’s most iconic Christmas markets, the mood is particularly glum. Businesses in the capital of Saxony had been looking forward to welcoming locals and tourists back to the smells of Glühwein and Bratwurst. Months ago they received the green light from state authorities to open up, but then came a shock last Friday: lockdown in Saxony, no Christmas markets, no tourism.

Local events manager Holger Zastrow, who runs two of Dresden’s Christmas markets, says his company’s losses amount to half a million euros (£420,000). Visibly browbeaten he accuses leaders of not caring about the country’s ‘Christmas culture.’ It’s not just the markets where tensions are running high. Dresden’s hotels had also been nearly booked out and were at 90 per cent capacity. Now they will have to cancel bookings and refund disgruntled guests. The losses could run into the tens of millions.

Not everyone is unhappy about the imposition of new restrictions, however: just over half of locals in the region approve of the cancellations because they are concerned about the rapid growth of Covid cases. Their concern perhaps seems to be well placed: hospitals across Saxony are rapidly approaching capacity with intensive care units in the largest cities of Dresden and Chemnitz at 95 per cent capacity each.

When I visit family and friends in Berlin, it is not uncommon to stumble upon men (and it is usually men) with ‘cloud cannons’ in the park.

Those in favour of another raft of restrictions point to the fact that the link between infections and hospitalisation has not been broken. Only just over half of the population in Saxony is fully vaccinated; the hospitalisation rate of 13 per 100,000 is nearly twice the UK’s 7.5, where 68 per cent of people are fully vaccinated. In Brandenburg and Thuringia, the vaccine rate is 61 per cent – much lower than the EU’s 67 per cent average.

Is there a simple explanation for this low vaccine uptake in parts of Germany? Given that Germany and Austria are typically seen as stable democracies, mistrust when it comes to the vaccine roll-out is hard to square.

One of the big problems in both countries when it comes to vaccines is a perceived lack of leadership. Austrian chancellor Sebastian Kurz resigned last month amidst a corruption scandal; in Germany, the outgoing Merkel cabinet has the feel of a lame-duck administration.

In the absence of any clear leadership, government messaging in both countries has been muddled. According to a survey conducted last week, two thirds of Austrians think their government’s Covid policy is ‘bad’. Meanwhile Germany’s health minister has caused confusion by calling the Moderna brand the ‘Rolls Royce’ of vaccines while BioNTech apparently was the ‘Mercedes’. This clumsy analogy was Spahn’s attempt to reassure vaccine sceptics who had been wondering whether the government was only promoting Moderna ‘to avoid the expiry of those vaccines in the first quarter of 2022.’ Unsurprisingly, it did not allay any doubts.

Among a significant portion of Germans and Austrians, there is also a shared cultural suspicion towards the field of science. One recent survey showed that 29 per cent of Austrians believed that scientists were dishonest; another quarter were undecided. That makes Austria the second-most science-sceptic nation in the EU, only trumped by the Germans.

Anecdotal evidence suggests such feelings are widespread. When I visit family and friends in Berlin, it is not uncommon to stumble upon men (and it is usually men) with ‘cloud cannons’ in the park. Their aim is to destroy poisonous ‘chemtrails’ that are supposedly spread by planes containing psycho-active chemicals which make whole populations compliant like sheep. Plenty of my friends and family members in Germany have long raised eyebrows at me for believing in what they like to call ‘conventional’ medicine, preferring homeopathic remedies themselves.

A related problem in Germany is the sharing of conspiracy theories, which roughly a third of Germans at least partially subscribe to, if recent surveys are to be believed. From the Reichsbürger movement, which denies the legal existence of the German state, to German chapters of the American QAnon movement, the country has a colourful array of groups, some with thousands of members. Vaccine rejection is a view that many of these organisations hold in common.

Yet it is important not simply to dismiss those who haven’t had their vaccines as simply siding with conspiracy theorists. Some Germans are understandably anxious about the vaccine’s underexplored side-effects. At the start of the pandemic, an estimated ten per cent of Germans were undecided if they would want to get the vaccine when it was available; another ten per cent said they were more negative about it but not completely averse. Notably, a third of women were sceptical compared to only a fifth of men, with similar patterns in Austria.

Unfortunately both Germany and Austria have decided not to engage with the moderate sceptics but to force the issue instead. The approach instead has been to combine a lack of steady leadership with harsh legislation, including a full lockdown and compulsory vaccination in Austria and talk of both in Germany. The result is widespread and increasingly angry demonstrations on the streets of both countries as people’s suspicions and anxieties are confirmed rather than allayed.

Is it time for a different approach? Germany’s complex vaccination history shows that education and reassurance is a much more effective way to increase uptake. The then newly-created German government made the smallpox vaccination compulsory as early as 1874, vaccinating children in schools with or without their parents’ consent; even so, it only ever reached around two-third of the population. Diphtheria vaccinations, on the other hand, remained voluntary but were supported by campaigns and education, convincing over 90 per cent of the population to accept it.

What seems certain is that Austria and Germany cannot force their way to higher vaccination rates – such a strategy is in danger of backfiring spectacularly.

The confusion at the heart of social care

Boris Johnson’s majority plunged to just 26 last night, following a rebellion over controversial changes to social care plans. Means-tested, state-funded payments will no longer count towards the £86,000 limit on the amount people will have to pay for their care. Those with initial assets worth less than £186,000, and who have received such help, could be worse off as a consequence. Critics have pointed out that this is likely to disproportionately affect residents in the North or the Midlands because of differential house prices.

Johnson’s government isn’t the first to tie itself in knots over the issue of social care funding. Successive administrations have failed to bring about reform over the past 25 years, with most proposals swiftly abandoned.

And while governments procrastinated, the fuse on our demographic time bomb has shortened. The Office for Budget Responsibility projects spending on social care will increase by about 0.8 per cent as a share of national income over the coming few decades because of population ageing. Political pressures have already led, and will continue to lead, to even greater increases in spending.

We should not be taking money from average taxpayers, many of whom are not homeowners, to assist those living in houses worth millions

The Tories’ plan is based loosely on the Dilnot proposals from 2011 — which suggested a more generous means-testing threshold and a cap on care costs — but it includes a ratcheting up of national insurance rates to foot the bill, and then a permanent new levy which further complicates our crazy tax system. The manifesto-busting hike was presented as a long-term fix — but it means the tax burden for working-age people will increase to prevent wealthy pensioners from needing to sell their homes to pay for care.

But here’s the major flaw with the current social care debate: funding for the elderly falls into two distinct subsets, which are almost deliberately mixed up. First, we must ask how we provide for those who have neither income nor assets to pay themselves. The secondary issue, which receives vastly more attention, is how we assuage fears that those with the means will be expected to fund their own care. In short: it simply isn’t true that Johnson’s social care plans will ‘leave the poorest in England paying a larger share of costs’.

The first is a genuine problem: in recent years there has been a squeezing of local authority budgets which are used to provide care for those who cannot afford it — including, incidentally, the large numbers of younger adults needing social care — and the system is creaking at the seams. But there is too much concentration on allowing old people to bequeath their homes to their children, and it has impeded discussion over the wider issue of funding.

A decade ago, Andrew Dilnot acknowledged that the risk of individuals needing to use their own financial assets to pay for care was intrinsically insurable. We insure our valuables against theft, or we don’t and we accept that, if robbed, we lose everything. Of the 22.6 million homes in the UK, over three-quarters have insurance. But Dilnot hit a stumbling block when he discovered that private providers across the globe are reluctant to provide such insurance, believing that people simply don’t want to insure against growing old and infirm.

What no one articulated, until former secretary of state for social security Lord Lilley put it forward, was the possibility of having the public sector underwrite insurance and set up a public body to provide it. Determined free marketeers might argue that the state shouldn’t be involving itself in matters of insurance. But it’s a low-risk activity, which may become commercially viable, and complex problems often preclude straightforward solutions.

The proposal would bring the housing assets of the well-heeled elderly into play without obliging them to sell their houses. They would be presented with the option to take out a policy paid for in the form of a charge on the value of their house. The costs of social care would be deferred, until death or the sale of the property. If they decline, they have shaky grounds for complaint when the time comes to pay the bill. Those living in poverty would be supported by a state whose finances would be in better shape given we would no longer be subsidising the asset-rich.

We should not be taking money from average taxpayers, many of whom are not homeowners, to assist those living in houses worth millions. Nor can we continue to slap sticking plasters onto this festering wound, continually expanding government spending. The Johnson approach has been rejected by previous governments for good reason. Foreseeable demographic pressures on public sector finances will lead future generations to regret this government’s fudge.

Is Joe Biden ready for the looming war with the Fed?

He isn’t especially bothered by global warming. He doesn’t think monetary policy has very much, if anything, to contribute to combating racism, promoting gender equality, or making the world a fairer place. And he doesn’t want to go to war with Wall Street, or bring any billionaires to heel. By re-appointing Jay Powell, a Republican first chosen by Donald Trump, as chairman of the Federal Reserve, Joe Biden has finally stood up to the Democratic party’s left wing. And yet, perhaps without realising it, Biden is also setting up what will sooner or later turn into an epic fight with the central bank over economic policy. This is a battle that could make or break his presidency.

After all, there is no more important position in the global economy than the chair of the Federal Reserve. The person running the central bank of the United States controls what remains the world’s reserve currency. He or she can’t exactly dictate what will happen to interest rates, currencies, bond yields and stock markets around the world. But they have a heck of a lot more influence than anyone else. This is why the appointment of Powell matters.

Powell is a familiar figure, and he is committed to stability

With the post up for re-appointment, the left of the Democratic party – which has so far been in complete control of Joe Biden’s administration – was campaigning for someone who would radically reinvent the Fed, by focussing on issues such as climate change, racism, sexism and inclusiveness. Perhaps, most of all, they wanted a person who would enthusiastically finance the wild spending the administration plans with a flood of printed money.

They’ll be sorely disappointed by Biden’s choice: instead, they are getting a fairly traditional, cross-party, independent central banker who worries about stuff like the money supply and the stability of the banking system. For the first time since he took office, Biden had finally managed to stay awake for long enough to face down the left of his party, and make a consensual, centrist appointment.

The markets already like that. Powell is a familiar figure, and he is committed to stability. And yet, while Biden may not realise it, he is also setting up an epic fight with the Fed.

Inflation in the United States is starting to run out of control. It hit 6.2 per cent this month, its highest level since 1990, and it shows little sign of coming down any time soon. There is not any real mystery about the reason why. Biden’s coterie of radical economic advisers, egged on by cheerleaders such as Paul Krugman in the New York Times, have embarked on an epic spending spree, financed by printed money. Cash has been sprayed around as if he has no meaning, with little thought given to how it will all be paid for.

Not surprisingly, all those extra dollars have led – not to higher productivity, or a revival of manufacturing as Biden’s clique hoped – but to higher prices and soaring asset markets. As a result, at some point, Powell is going to have to hike interest rates, and sharply, to bring that under control. The Fed doesn’t have any magic wand to control inflation. In the words of one of the most famous holders of the office – William McChesney Martin, who ran the bank from 1951 to 1970 – it simply ‘takes away the punchbowl just as the party is getting started’. When that happens, the US will be pushed into a recession. The left will blame Powell – and eventually Biden will have to choose between backing the central bank or, once again, giving in to the left of his party.

It’s Harry, not Meghan, who’s the real problem

Who or what drove Harry and Meghan to leave the royal bosom for the land of slebs on the other side of the Atlantic? That’s one of the central questions of a new two-part documentary, The Princes and the Press, that aired on the BBC last night.

The obvious suspect is the dreaded British media — barging, intrusive, xenophobic — riddled with prejudice, we’re told, against a mixed-race American in the monarchy. But the jostling between royal households seems equally responsible. After the early days of Hazza and Megz, a clear jealousy from some of William and Kate’s people began to seep into the media. The younger brother and his American wife were suddenly the darlings of the British press. ‘Work-shy William’ and ‘waity Katie’ were left looking like yesterday’s royals.

Today, Kate and Wills are the PR golden couple while it’s all gone wrong for Harry and Meghan. What happened? Like all media darlings, eventually less favourable coverage began to surface (not least from Meghan’s father). There were allegations that she was difficult to deal with, that courtiers were unhappy and leaving in droves — something that her lawyer, given specific permission to speak to the BBC, expressly denied. Then there was so-called tiara-gate, where Meghan was supposedly refused royal jewellery, an incident that resulted in either her or her royal fiance being marched in before the Queen. It is worth noting too, that much of this gossip initially went unreported. Dan Wootton, then of the Sun, explained that it took a good six months before these whispers appeared in the press. A lifetime in news cycles. There was clearly a reticence to go after the new royal pair. But eventually a narrative began to take hold of a demanding couple, insisting on American-style service from a British institution.

It’s the deal they make: they get to live in opulence and in return we, the people who pay for it, who give them that grandeur, receive fragments of their lives

Frustrating, no doubt, but these kinds of stories happen in royal land. William certainly knew how to deal with negative press, calling in newspaper editors for one-on-one meetings and hiring shrewd press officers from the world of politics. But Harry went further, putting out public statements decrying perceived media wrongdoing and taking multiple newspapers to court. William played the game — his brother refused. This, more than anything, explains the Sussexes’s departure from Britain.

It’s clear that Harry is the one who disrupted that seemingly ancient dance between journalists and family. To those on the outside, that dance may at times seem unedifying. One BBC interviewee, Gavin Burrows, a private investigator who reportedly worked for the News of the World, described the abhorrent targeting of one of Harry’s former girlfriends. Chelsy Davy’s personal history was viciously sought out: ‘Medical records… had she had an abortion, sexual diseases, ex-boyfriends? Vet ’em, check them’. It is difficult to feel anything but abject sympathy for Harry, not to mention poor Ms Davy. No doubt the older brother also felt for Harry and Chelsy. After all, Kate’s phone had been hacked over a hundred times in the early days of their relationship.

But for all the grubbiness, the truth is that the media and the royal family feed off one another. It is a kind of symbiosis: the royals are able to build a story around their lives; the media, by contrast, are able to serve and thrill their audience.

Harry must know this. He knows what’s expected of a royal and he knows how to punish those journalists who overstep the mark. Yet, as the documentary makes clear, he chose to ignore those unspoken rules of engagement. Meghan, the outsider, couldn’t have understood the full depths of what royal scrutiny entailed. But her husband did. To be born into the firm means a different level of understanding.

It is Harry who failed. At one point, the BBC’s royal editor Jonny Dymond, not unsympathetic to the couple’s cause, described a frosty interaction Harry had with journalists on a press trip in 2018. ‘He can’t bear the press, he can’t bear the media. He has a visceral reaction to cameras and notebooks — to journalists,’ explained Dymond, before show-acting a vomiting prince. You might think, who can blame Harry? The press is rapacious. In his eyes, they bear responsibility for his mother’s death.

But that’s the life of a royal. A life of cameras and notebooks, of polite hellos and forced smiles. It’s the deal they make: they get to live in opulence and in return we, the people who pay for it, who give them that grandeur, receive fragments of their lives. There is cruelty in that gilded cage.

Perhaps one of the most revealing moments came from Omid Scobie — the co-author of Finding Freedom, whom Meghan admitted to the courts of having briefed after initially denying it. Scobie explained that it was Harry, not Meghan, who drove the initial anti-press strategy. Meghan felt that she was media savvy enough to engage with the British press pack. Harry objected. Instead, he declared a form of war. He denied reporters proper coverage of the couple’s engagement, attempting to bar them from the royal wedding itself.

It is something the firm knew couldn’t work: you cannot say what you like and do as you please and continue to be a royal. Refuse to honour your side of the deal and the other half, that opulence and grandeur, collapses. The pact is what makes them. Break it, and you break the monarchy. It’s a hard lesson, one that the royals should have learnt from Harry’s mother. The couple wanted to be their own people — to have ‘a voice’, whatever that means. The lesson that both the Queen and the lesser royals have learnt is that ‘a voice’ is impossible. The House of Windsor should be seen but never really heard.