-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Is Meghan wise to go into American politics?

On a long-ago Remembrance Sunday, it fell to me, as a new service equerry, to present the Prince of Wales with his wreath to lay at the Cenotaph. The fact that the Cenotaph in question was in Hong Kong — still a British Crown Colony at the time — gives the memory a sepia tint. Adding to the retro imperial theme, His Excellency the Governor wore full dress uniform, complete with pith helmet and ostrich feather. As I waited nervously to play my walk-on part, I had time to realise how lucky I was to witness such vanishing theatre.

The rest of Hong Kong cheerfully went about its business while we performed our solemn rite. Yet any locals who paused to watch the immaculate little ceremony couldn’t have guessed that a tetchy protocol impasse had only narrowly been averted. In the absence of the Queen, the first wreath would normally be laid by her representative, the Governor. But the Prince’s advisors argued that since he was present in person and surely the next best thing to the sovereign herself, he should take precedence. As I recall, after a rather tense phone conversation with Buckingham Palace, a ruling was handed down. The Prince’s wreath — though laid with consummate dignity — was laid after the Governor’s.

So to this Remembrance Sunday, from which Her Majesty’s absence inevitably stirred anxious speculation about her health. Only six times in her reign has she missed the sacred act of tribute to the Glorious Dead, and then only because she was either pregnant or overseas on tour. We’re told the reason is unconnected with her recent period of enforced rest but such assurances give only chilly comfort. We hope in our hearts she’ll be back next year. But, as the earnest tableau around the colonial Cenotaph reminded me, earth’s proud empires do pass away, usually taking their ruling families with them. How reassuring, then, to glance at the Foreign Office balcony where the royal wives were gathered and find reason to be hopeful for the House of Windsor.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, the Duke and Duchess of Sussex observed Veterans Day at the Salute to Freedom gala at the USS Intrepid museum in Manhattan. Most talk was of the Duchess’s dress — a dramatic poppy-red creation by Carolina Herrera. High point of the formal proceedings was the presentation by the Duke of the inaugural Intrepid Valor Awards to five service members, veterans and military families living with the invisible wounds of war. Good, solid royal stuff, albeit in a distinctly non-British context. Yet the courtier/bureaucrat in me couldn’t help seeing shades of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, grins fixed amid the gala-goers. Nowhere does charity glitz like New York but, since it starred the Queen’s grandson, there’s legitimate curiosity about the event’s protocol, status and reporting arrangements. These are the kind of questions that might have been directed to Harry and Meghan’s former communications secretary, Jason Knauf, but Mr Knauf has long since distanced himself from Team Sussex and now runs the Cambridges’ Royal Foundation. A smart career move given his recent front-page appearances as the man who cast doubt on Meghan’s recollections about her correspondence with her father while suggesting she knew more than she admitted about her role in the suspiciously sympathetic Finding Freedom.

Meghan seems to be diversifying into American politics, reportedly making personal calls as ‘the Duchess of Sussex’ to senators to lobby for laws on social issues. In Britain, such intervention to influence public policy would be dangerous constitutional overreach for a member of the royal family (though that hasn’t stopped some). In Meghan’s defence, friends say she’s just doing her part as an engaged citizen. There’s certainly no shame in that as a title, and some might argue that in the egalitarian USA nothing grander is required or even desirable. After all, according to Thomas Jefferson: ‘There is not a single crowned head in Europe whose talents or merit would entitle him to be elected a vestryman by the people of any parish in America.’

Talking of elections, here in Jefferson’s home state of Virginia we just voted in a new governor. The results both here and in neighbouring New Jersey were a notable success for the Republicans and have been widely interpreted as a sharp warning to Joe Biden’s Democrats as we approach next year’s midterms. All that may be true, though for me the real highlight was a sign at the polling station advertising ‘Drive-thru voting for over-65s’. Suffrage without the suffering. Now that’s what I call democracy.

The Palace vs the Sussexes

What will become of the British monarchy after Elizabeth II? It’s a question that many would prefer not to ask. But the Queen is 95, her husband died earlier this year and she’s pulling out of engagements she’s rarely missed in 69 years on the throne. More honest royal sources confirm the obvious: she’s had to take another significant step away from public life. From now on she will conduct more duties over video calls. She’ll save her energies for key events such as the Christmas broadcast.

Which leads us to the thorny matter of her succession. Queen Elizabeth has managed to sustain the prestige and influence of the crown in an obsessively democratic age. Will her heir, Prince Charles, and his sons be able to replicate that remarkable achievement? Recent years suggest that the answer might be no. We all know the grubby allegations about Prince Andrew. We’ve also watching another tabloid drama with an American subplot unfold: the House of Cambridge vs the House of Sussex, Kate and Wills vs Hazza and Megz, ‘brothers at war’, etc.

To sustain interest — or engagement (buzzword) — a modern monarchy must offer some soap operatic elements. At least that’s what Palace PR wizards believe. But the clash between the younger royals threatens to turn the whole Windsor show into reality TV, a ghastly clash between drama-queen princes and their feuding wives. It’s titillating stuff, no doubt. It’s also vulgar, which is dangerous for an institution that is meant to be the opposite. At some point people grow bored and turn off.

The chief problem is that Harry and Meghan appear to have been driven mad by fame — an unfortunate twist given their efforts to publicise mental-health issues. Last week, Prince Harry revealed that he, a postmodern Cassandra, had warned Twitter’s founder Jack Dorsey that ‘his platform was allowing a coup to be staged’ ahead of the 6 January riot in Washington, DC. As a ‘commissioner’ for the Aspen Institute on ‘Information Disorder’, Harry is trying to establish himself as a great enemy of fake news. This week, on the Sussexes’ official Archewell website, he published 15 rules to which the media should adhere. The timing was perfectly ridiculous, since just five days earlier his wife had been forced to admit that she had misled a British court in the Sussexes privacy case against the Mail on Sunday.

Harry and Meghan’s great folly is to have convinced themselves that they can be supreme masters of their image. Last week, their former spokesman Jason Knauf sensationally revealed how heavily involved the couple have been in crafting their own PR. Texts between Meghan and Knauf showed her saying she’d addressed her father as ‘Daddy’ so that ‘in the unfortunate event’ that it leaked she would ‘pull on the heartstrings’. She also said that everything she drafted was written ‘with the understanding that it could be leaked’.

Knauf is due to leave royal employment next month to live in India. Yet his parting shot at Harry and Meghan is highly revealing. He left the Sussexes to work for the Cambridges and closely assisted Kate and William in their roles at the Royal Foundation. ‘It seems extremely unlikely that he would not have at least let Catherine and William know about his upcoming testimony,’ says a well-placed source. ‘If they wanted to stop him disclosing Palace communications, they could surely have done so.’

Before the initial hearing against the Mail on Sunday, Knauf and the three other press aides to Harry and Meghan — the so-called ‘Palace Four’ — stayed quiet. After the judge ruled against the newspaper in February, however, Knauf decided he could no longer keep schtum. A month after the judgment, on 2 March, it emerged that he’d filed bullying complaints against the Duchess. He also changed lawyers.

Harry and Meghan’s great folly is to have convinced themselves that they can be supreme masters of their image

On 7 March, that big Oprah interview came out, in which Meghan accused the Palace aides of being complicit in a reactionary plot to silence her truth. ‘They were willing to lie to protect other members of the family,’ she said. ‘They were not willing to tell the truth to protect me and my husband.’

Knauf is gay, progressive, woke even. It must have infuriated him and other aides to watch their former employers, riddled with self-pity, describing how they were so mistreated by a fusty and racist old institution. The truth is that the ‘Palace Four’ went to enormous lengths to promote the ‘Fab Four’ — William, Kate, Harry and Meghan — before the two households fell out in 2019. There was excited talk about the younger royals becoming a ‘philanthropic powerhouse’. But the Four weren’t so Fab. In fact, they couldn’t stand each other.

Even after the Oprah interview, Palace operators have tried to engineer a rapprochement between the brothers. Various occasions presented themselves, notably the funeral of Prince Philip in April and the unveiling of the Diana statue in July. But sources say that Harry showed little enthusiasm to do more than the bare minimum of showing up.

Poor Harry has been lost to La La Land. Through Archewell, he and Meghan are running a new, hyperactive publicity operation on the other side of the Atlantic. It’s monarchy with American characteristics. Last week, for instance, they didn’t mark Remembrance Day; they attended Veterans Day events in New Jersey and New York. It all makes useful content, no doubt, for the fly-on-the-wall documentary they are bringing out as part of their £112 million deal with Netflix. There’s also the $20 million, tell-all book deal with Random House.

All the cringe-inducing hoopla around Harry and Meghan is beneficial to William and Kate, in a creepy PR way. Once the ‘reluctant royal’, William now emerges as the dutiful and diligent future king. The newspapers took particular delight in the images of Kate in her modest black Remembrance Sunday dress, a contrast to Meghan and her low-cut poppy-coloured number. You don’t have to be a fashion expert to spot the difference. Moreover, a shared hostility towards the troublesome pair in America has brought William closer to his father and the new press team representing Charles and Camilla at Clarence House.

Charles, who may soon be king, has long wanted to streamline ‘the Firm’ — and limit the possibilities for embarrassment by shrinking the number of serving royals. He probably didn’t imagine that would include cutting out one son in order to promote another. Harry, for his part, could never have dreamed a few years ago that he would be antagonising his family by running a trashy spin-off operation from Beverly Hills.

The recent episodes of the real-life Crown seem rather sad and cruel. But nobody said that monarchy was meant to be fair.

Why do cartoonists struggle to break America?

‘Cartoons are like gossamer and one doesn’t dissect gossamer.’ So says Mr Elinoff, the fictional cartoon editor of the New Yorker in an episode of Seinfeld, when trying to explain a cartoon to Elaine. Elaine isn’t satisfied. Mr Elinoff suggests the cartoon is a commentary on contemporary mores, a slice of life or even a pun. ‘You have no idea what this means do you?’ says Elaine. ‘No,’ he concedes.

The scene sums up the problem of understanding the New Yorker’s sometimes oblique sense of humour — and may come as a relief to the many British cartoonists who have tried and failed to break into the Big Apple’s literary bastion. It’s reassuring to think that even Americans as funny as Seinfeld can be baffled by New Yorker jokes. Yet still the mystique survives, and most British cartoonists have had a stab at getting into the magazine, lured by its great cartoon history (James Thurber, Saul Steinberg, Charles Addams) and the money: it pays more than ten times as much for a cartoon than UK magazines.

Former (real) cartoon editor Bob Mankoff said in a Ted Talk: ‘The New Yorker occupies a very different space. It’s a space that is playful in its own way, and also purposeful, and in that space, the cartoons are different… New Yorker humour is self-reflective.’ Elsewhere, he recalled that when he was finally rewarded with a contract in 1980, the contract referred not to cartoons but to ‘idea drawings’, what Mankoff calls the ‘sine qua non of New Yorker cartoons’: a drawing that requires both cartoonist and reader to think. Indeed, there is Sam Gross cartoon of a landscape with a large sign reading ‘STOP AND THINK’ and a man saying: ‘It sort of makes you stop and think, doesn’t it?’

We reckon if bawdy humour and puns were good enough for Shakespeare, they’re good enough for us

So New Yorker gags are more philosophical than their British counterparts. Here, virtually anything goes — sick jokes, coarse jokes, badly drawn jokes, puns. The New Yorker has a metropolitan disdain for crudity and eschews wordplay. We reckon that if bawdy humour and puns were good enough for Shakespeare, they’re good enough for us.

New Yorker cartoons also tend to be more lifestyle-oriented, and inhabit a more whimsical world of middle-class social gatherings, boardrooms, domestic relationships and navel-gazing neuroses. Some recent ones look like architectural drawings, whereas British cartoons tend to inhabit a more traditional cartoon landscape: big noses, goofy expressions, surreal situations.

Humour is, of course, a serious business, and from the outset nobody took it more seriously than the New Yorker. Its legendary founding editor Harold Ross was obsessed with perfection and detail. Thurber recounted how Ross studied a cartoon of a Model T Ford on a dusty road and demanded ‘Better dust!’ He would also scan for hidden phallic symbols and sent a photographer to the UN building to check whether a drawing of its windows was accurate. Cartoons that fell below his standards would receive a ‘Get it out of here!’

Today, aspiring New Yorker cartoonists just have to endure months of silence once their ideas are submitted. Success is greeted with a restrained ‘Okay’ from cartoon editor Emma Allen. Two British cartoonists who have enjoyed such success — following on the heels of a few UK predecessors such as Ronald Searle, H.M. Bateman, and Heath Robinson — are Will McPhail and Carol Isaacs (who draws under the pseudonym The Surreal McCoy). Both are adamant that the work they submit for the New Yorker is essentially no different from that published in British magazines.

‘My approach is more or less the same for both sides of the pond,’ says Isaacs. ‘Maybe tweaking the grammar and spelling for the Americans. I love Seinfeld and the Marx Brothers as much as I love Spike Milligan and Fawlty Towers. As they say over there, go figure.’

McPhail thinks the recent trend towards more absurd and bizarre cartoons in the magazine have helped his cause. ‘Those are the cartoons that genuinely make me laugh, the ones where I don’t know why it’s funny. I’ve always seen a lot of the humour in British cartoons like maths equations. They’re perfectly balanced and everything that is set up at the start of the equation works out correctly by the end. But I like cartoons where you can’t see “the strings”, if that makes sense.’

Is familiarity with New York essential to inhabiting the New Yorker mindset? Isaacs thinks not. ‘After all,’ she says, ‘there are many New Yorker cartoonists who’ve never set foot in New York. Their sense of humour is perhaps more about the absurd than anything else — and that knows no borders.’

McPhail confesses that he used to make pilgrimages to the New Yorker offices just to submit in person to Bob Mankoff. ‘I of course pretended that I just happened to be in New York at the time. So I do think there’s a certain amount of them needing to know you’re serious about it before they publish you, like “Wow, he’s come all the way here to get rejected in person!”’

Each week thousands of submissions are boiled down to some 50 acceptances. The closest I’ve come to making the grade is when I saw a cartoon identical to one I once drew for Private Eye (of a drunk ventriloquist in the gutter whose dummy is vomiting) on the cover of a book entitled The Rejection Collection: Cartoons You Never Saw, and Never Will See, in the New Yorker.

Battle for Britain | 20 November 2021

Decent dream pop: Beach House’s Once Twice Melody reviewed

Grade: B+

Everything these days devolves to prog — and not always very good prog. Where once synths were vastly expensive, difficult to master and hell to maintain they are now in a place beyond ubiquity; every sound you want conjured by the press of a key, your song suddenly washed over with sonics that make it sound more important than it really is. It almost makes you yearn for Yes and ELP — at least they knew they were pretentious dullards using electronic wizardry to elevate the slightest of compositions.

Dream pop and its self-harming kid sister shoe-gazing — both genres dating from the mid-1980s and the likes of the Cocteau Twins — were always going to lend themselves to prog’s grandiosity. Victoria Legrand — niece of the pianist Michel Legrand — and Alex Scally are probably the last two middle-class white folk still living in Baltimore. They comprise Beach House, who have been around since about 2004 and become grander with each recording, leading up to this — a double album that will be released in four separate ‘chapters’, of which this is the first.

It is heavily infested with morose atonal washes of sound, but strip that stuff away and you have a decent dream pop album; plaintive tunes that linger a little in the memory. The stand-out from this ‘chapter’ is ‘Superstar’, a chunk of agreeably chugging pop dressed up beyond its years and sung with the requisite misery by Legrand. It slightly overstays its welcome. The other three songs are similarly languid and pretty. I don’t know that I could take all four ‘chapters’ of this, mind, without wishing to beat them about the head with a dead halibut.

The art and science of Fabergé

After all the magnificent presents she’d received from his workshop, Queen Alexandra was eager to meet the most famous jeweller in Russia. ‘If Mr Fabergé ever comes to London,’ she said to Henry Bainbridge, a manager of the design house, ‘you must bring him to see me.’ Peter Carl Fabergé paid a rare visit to the capital to inspect his new shop — the only one located outside the Russian empire — at 48 Dover Street in 1908. ‘The Queen wants to see me! What for?’ he asked an exasperated Bainbridge. ‘Well, you know what an admirer she is of all your things.’ Insisting that she would not wish to be troubled, Fabergé demurred, polished off his lunch and requested the time of the next train.

Fabergé, whose work for both Edwardian and Romanov society goes on display at the V&A this week, was by most accounts a modest man of immodest creativity. Of Huguenot heritage, he grew up in St Petersburg, where his father had established a traditional jewellery business, and trained as a goldsmith before completing the Grand Tour. Inheriting the family company in 1872, Fabergé fils proceeded to transform and enlarge it until he stood at the head of 500 innovative workers, among them his younger brother, Agathon, and four sons.

While the ‘soul’ of the firm remained in St Petersburg, a second branch had opened in Moscow and a third in Odessa when Fabergé began to weigh up Paris and London as possible locations for an international outpost. His choice of London in 1903 was influenced by both its growing reputation as a meeting point for buyers, and the connections between the British royal family and his patrons in Russia.

To Fabergé’s manufacture of cooking pots were added orders for components for hand grenades

Alexandra, consort of King Edward VII, was the sister of Emperor Alexander III’s wife, Maria Feodorovna, and Edward’s niece, Alexandra Feodorovna, was married to Emperor Nicholas II. It was at Alexander’s instigation that Fabergé began to produce his famous line of Easter eggs. The first and, to my eye, the most beguiling, consisted of an outer shell of white opaque enamel encasing a gold ‘yolk’, which contained a pretty golden hen with ruby eyes, concealing a diamond crown and pendant. Almost every year after Maria received it as a present, Fabergé took orders for eggs from the court, to which he had been appointed Supplier and Appraiser of the Cabinet of His Imperial Majesty, permitting him to mark his stationery with the state emblem, and enter the palaces.

Each egg was to be more extraordinary than the last, the challenges of which are only too obvious. It became less about the egg than the surround and the surprise. After the simple white hen’s egg of 1885 came an egg forming part of a model of Uspenski Cathedral, complete with chiming clocks and a wind-up mechanism to play Easter hymns, and an egg split across the top as if scalped in an eggcup to reveal a miniature model of the entire Alexander Palace. Both are among more than 200 pieces going on display at the V&A. Mirrored ceilings have been installed at the gallery to show off the glitz from all directions. Only the eggs made during the first world war broke the cycle of extravagance. Those made for 1915 were adorned with the Red Cross in honour of the Romanov women’s medical work. They split open to reveal painted religious iconography rather than the usual baubles or automata.

Although, surprisingly, Fabergé was not involved in crafting the objects, he oversaw the work, and organised his employees into groups under workmasters he hired himself. These workmasters, chief among them Michael Perkhin, a Russian, and Henrik Wigström, a Finnish-Swede, were allowed to initial their pieces. In addition to crafting eggs, they made a wide range of decorative objects, such as clocks, cigarette cases, letter openers, model animals and all manner of what Kieran McCarthy, the exhibition’s curator, calls ‘nonsensical objects to delight’. Who doesn’t need a silver cigar-cutter in the shape of a Japanese carp?

The London items are among the most unusual. Scenes of the British countryside and houses, including Sandringham, were presented in gold, enamel and nephrite. Statuettes of famous figures from British culture were modelled from a rich variety of stones. It is quite something to behold a hoary Chelsea Pensioner in black jasper trousers and boots. It is still more startling to stumble upon a portly and, dare I say it, rather toylike John Bull. While the former was purchased for £49 15s by King Edward for Alexandra, the latter was snapped up by Emperor Nicholas II before it even reached our shores. It is hard to say who had the perkier sideburns, the tsar or flame-haired Bull.

The real wonder of Fabergé lies in the ingenuity of the creations. As McCarthy says, the craftsmen could ‘take a piece of quartz and turn it into a quince’. Many of the materials they used were peculiarly stubborn and difficult to piece together. Often, the techniques have been lost, or prove impossible to recover working backwards from the finished objects. The seamless coherence of the gold, which like their other materials Fabergé sourced principally from the Ural mountains, defies comprehension.

The Fabergé workers were quite literally at the cutting edge of new developments in materials. They carried out so many experiments with coloured enamel that Bainbridge likened their workshops to research laboratories. One of the young female employees, Alma Pihl, achieved prominence within the firm as a designer and worked wonders with platinum, which had only recently started to be used for jewellery. After designing a range of brooches inspired by snowflakes, she conceived the transparent, ice-like rock crystal and platinum Winter Egg adorned with 1,660 diamonds surrounding a platinum and diamond basket of quartz spring anemones.

During the war, many of the workers were conscripted, and the emphasis fell away from luxury items in favour of necessities. To Fabergé’s manufacture of cooking pots were added orders for components for hand grenades and artillery plugs. Worse was still to come.

The confiscation of jewels by the Bolsheviks following the October Revolution of 1917 saw many of Fabergé’s masterpieces destroyed. With the workshops no longer able to supply it, the London branch closed, and remainder stock was sold off to a French jeweller on New Bond Street. Two of Fabergé’s sons were imprisoned before one of them lent his assistance to the state treasury in examining and breaking up jewellery — very likely some of his family’s own handiwork — for the raw materials.

The penultimate room of the exhibition, the darkest in what the curator describes as a ‘glittery, wonderful, joyful’ show, follows Fabergé’s flight from Russia in the wake of the Romanov assassinations. Having reached Riga, he reunited with the rest of his family, before proceeding surreptitiously to Finland. Finally, in 1920, he reached Lausanne. ‘Such a life is not a life any more,’ he would say, ‘when I cannot work or be useful.’ He died later that year of liver cancer. For all that he had lost, hundreds of his creations had been preserved, some so well that it is believed that at least two of his eggs may still be out there, ready to be hunted.

The true superhero is Douglas Wolk – who has read through 27,000 Marvel comics

In March 1963, the Fantastic Four had a fractious encounter with Spider-Man and a dust-up with the Hulk — a busy month which effectively launched the Marvel Universe as an ecosystem of characters whose individual stories all contributed to one giant narrative.

There is nothing quite like it: an endless, collaborative roman-fleuve of wildly variable quality, constructed over several decades by hundreds of writers, artists and editors, driven by a combination of personnel changes, marketing schemes and hasty improvisations. As a 14-year-old Marvel nut, I had a decent handle on it; but now, if I nostalgically check out a character’s Wikipedia page, I’m swamped by an unfathomable splurge of deaths, resurrections, shifting alliances and parallel universes. Who can keep up with this stuff? Who would want to?

Perhaps only Douglas Wolk. The critic committed himself to reading every single Marvel Universe comic book published between 1961 and 2017: around 27,000 issues, running to more than half a million pages. That’s quite a task. An even bigger one is to condense the experience into a book that isn’t as bewildering and exhausting as its subject matter. Fortunately, Wolk is a capable guide, wry, friendly and astute, who assures us: ‘What the story wants from you is not your knowledge but your curiosity.’ Now that Marvel’s film franchise, the MCU, is the world’s biggest, the story resonates far beyond the pages of comic books.

All of the Marvels is, necessarily, an unusual book. After 50 pages of amiable methodological throat-clearing, Wolk devotes chapters to crucial themes or characters, broken down into landmark issues and festooned with footnotes. It isn’t chronological, but along the way we learn how the middle-aged huckster genius Stan Lee (‘a con man who delivers the goods’) and artists such as Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko reinserted the superhero into the heart of American mythology in the early 1960s. Much depended on grumpy outsiders and the hubris of very clever men.

Lee and his colleagues bequeathed a mountain of raw material to subsequent writers, many of whom outdid the originators; it took 17 years for Dare-devil to realise its potential, 21 for Thor and 32 for Black Panther. You might call it licensed fan fiction: people who grew up with these characters get to reimagine them with few hard-and-fast restrictions. Change is inevitable but not necessarily permanent. Unless you’re Spider-Man’s Uncle Ben, death is rarely the end.

Wolk succeeds on two levels. He’s an astute close reader who can elucidate not just the chemistry between writers and artists but also the underrated role of colourers and letterers; and he tracks the evolution of Marvel’s abiding themes (‘the role of gods and the role of kings, where power really lives, what might be beyond the world we know’) with the right mix of respect and amusement.

It’s clear that current complaints that Marvel has become too woke are misguided. The 1970s gave us student protestors, sincere if shaky efforts towards racial diversity, and a Watergate-era Captain America so disgusted by his own government that he quit. Wolk points out that Marvel’s ‘sliding timeline’, in which the events of 1961’s Fantastic Four #1 are always 14 years ago, means that the 1970s no longer happened, but still. He digs into the letters pages to unpack a long, respectful dialogue between the writer Doug Moench and the reader Bill Wu about racial stereo-typing in Master of Kung Fu. These conversations are not new.

Most successfully, Chris Claremont’s sales-busting 1975-91 run on the X-Men established the mutants as a fluid metaphor for the Other. As Wolk writes: ‘X-Men became to comics approximately what David Bowie was to music — the signal to every misfit out there that they weren’t alone and that things might be okay after all.’ Claremont’s pioneering dedication to female characters coexisted with a marked taste for mind-control plots and fetish gear. Such individual idiosyncrasies, from Frank Miller’s infatuation with ninjas and vigilantes to Bill Sienkiewicz’s jagged impressionism, have made the comics far bolder and stranger than the movies they have inspired.

I would have liked more analysis of classic, self-contained narratives and fewer recaps of knotty, multi-character cross-over events. But then Wolk’s fundamental subject is the mad puzzle of continuity: the form of storytelling more than the content of individual stories. Current writers, such as Al Ewing and Jonathan Hickman, operate with a Wolk-like blend of knowledge, affection and irreverence, in playful conversation with Marvel’s heritage. The worst writers simply find ways to keep characters busy, while the best propose new answers to foundational questions.

Twenty years ago, this book would have been a niche proposition. Now, largely thanks to the MCU, universe-building is increasingly essential to movies and television, with billions of dollars riding on narrative plate-spinning and the rejuvenation of old IP. Marvel has been doing it for 60 years, if not always well, and this generous, freewheeling book explains how.

How Shane MacGowan became Ireland’s prodigal son

I once stood on a Dublin street with Shane MacGowan and watched little old ladies who can’t ever have been Pogues fans blessing him as they passed by: ‘God love you, Shane!’ On his 60th birthday, in 2017, Michael D. Higgins, the President, presented him with a lifetime achievement award, while Nick Cave, Bono, Johnny Depp, Sinead O’Connor and Gerry Adams applauded. He is, if not Ireland’s national treasure, then certainly its prodigal son.

Yet he was not even born in Ireland. He likes to make out that he grew up as a barefoot urchin on his grandparents’ farm, The Commons, in Tipperary, but in fact he was raised in Tunbridge Wells, in a big, detached house. His parents, Maurice and Therese, were Irish, but they moved to England before he was born. He went toa fee-paying school, Holmewood House, for seven years, where he was ‘brilliant’ at English and won a scholarship to Westminster. He didn’t have a hint of an Irish accent in those days.

But he spent all his holidays in Tipperary, and dreamed of it as his land of lost content. It became even more precious when his family moved to the Barbican in London, where the constant building noise drove his mother into deep depression. And he hated Westminster, because he was mocked for his crumbling teeth and sticking-out ears. He retreated into drugs; when he was l5 he was arrested for possession of speed, grass and acid. By l7, he was addicted to Valium and sent to Bethlem psychiatric hospital for six months. He spent his 18th birthday there.

In New Zealand, Shane painted himself and his hotel room blue, because ‘the Maoris were talking to me’

Soon after being discharged he saw the Sex Pistols — ‘the pop band I’d been waiting for all my life’. He loved punk’s energy, its rawness, its anger. His sister Siobhan says the family were all delighted. ‘Punk was a good thing for Shane; it had a lot of positive energy and he could do something, he belonged to something.’ Also, as Shane noticed, it increased his pulling power:

I always found it hard to pick up girls at discos cos I was so ugly, but the punk thing fuckin’ changed my life. It didn’t matter that I was ugly… nothing mattered. It was good.

So he went to all the punk gigs and suddenly he was famous when the NME ran a photo of him covered with blood under the headline ‘Cannibalism at Clash Gig’ — apparently a girl had bitten off his earlobe. After that he was recognised everywhere and acquired the nickname Shane O’Hooligan. He produced his own handwritten fanzine, Bondage, and A&R men consulted him when they were looking to sign punk bands. He advised Polydor to sign the Jam, and Paul Weller was so grateful he bought Shane’s Union Flag shirt for £500.

In l977, an art student called Shanne Bradley asked if he would like to audition for her band the Nipple Erectors, and he said: ‘Oh that’s my dream.’ He charged into her bedsit and ‘started rolling around on the carpet doing a really good Iggy impersonation. He proper screamed and everything and I just went, Yeah, you’re it, you’re the frontman. Perfect.’ They made their debut at the Roxy in September l977 and went down well with the crowd. For a moment they planned to marry, and Shane actually went to Finsbury town hall to apply for a licence, but then they drifted apart.

He found other girlfriends, other bands. Punk was fading by the 1980s, but then Dexy’s Midnight Runners had a hit with ‘Come on Eileen’ and Irish bands were all the rage. Shane formed Pogue Mahone (meaning ‘kiss my arse’), which had a regular gig at the Pindar of Wakefield pub in King’s Cross, and was soon signed by Stiff Records, though the name had to be changed to the Pogues. They had a string of minor hits — ‘Dark Streets of London’, ‘A Pair of Brown Eyes’, ‘Dirty Old Town’ — and were soon invited on their first US tour. Shane had never even been on a plane, and was thrilled by America: ‘They’ve got cars big as bars!’ That initial excitement fed into his immortal 1987 hit ‘Fairytale of New York’.

Back home he met the love of his life, Victoria Clarke, a beautiful girl from the Gaeltacht (whom he finally married in 2018). But they spent little time together. Frank Murray, the Pogues’s manager, was a slave-driver who kept the band endlessly touring — more than 200 gigs in one year — till Shane was driven berserk. He often forgot lyrics or even sang the wrong song, and in New Zealand he painted himself and his hotel room blue because ‘the Maoris were talking to me’.

Although his drinking was well known and enthusiastically accepted by his fans, he was increasingly addicted to hard drugs, including, eventually, heroin. He was desperate to leave the Pogues but, always afraid of confrontation, he waited for them to sack him. They finally did, on tour in Japan, and his only reaction was: ‘What took you so long?’ Bono lent him and Victoria his Martello tower at Bray and then they moved to a modest flat in Dublin.

He was still writing songs and formed his own group, Shane MacGowan and the Popes (‘no democracy — it’s a dictatorship’) which had some success, though never as much as the Pogues. But inevitably his drinking was taking its toll. And then in the summer of 2015 he had a bad fall which left him unable to walk. He has been in a wheelchair ever since.

Nowadays he needs carers to get him in and out of bed and he spends all day watching telly and drinking. But even if he never writes another song — and he probably won’t — he has left an unforgettable legacy. This biography is based on interviews with dozens of people who knew him well at various stages of his life and — like Shane himself — comes over as a bit chaotic but essentially good-hearted.

More penny dreadful than Dickensian: Lily, by Rose Tremain, reviewed

Rose Tremain’s 15th novel begins with a favoured schmaltzy image of high Victoriana: it is a night (if not dark and stormy, then certainly dark and wet) in the year 1850, and a baby has been left at the gates of Victoria Park. Then we have an uncanny detail: the baby is sniffed out by a pack of wolves, one of which bites off her little toe. Thankfully, a police constable finds her and walks through the night to Coram’s Fields to deliver her to the Foundling Hospital. From there she is sent to be fostered by a loving family on a farm in Suffolk for six years, only to return to the Hospital for a childhood of cruelty and abuse at the hands of the staff. We have already encountered her working as a wig-maker by day and dreaming at night of her execution by hanging.

Her crime is murder. This proves a weak drive for the narrative, however, as the novel moves at such a muddled clip, flitting back and forth in time, that the plot is a series of anti-climaxes. Lily’s childhood is intercut with her life as a young adult, but the former is elided to such an extent in the latter that its primary purpose seems to be to demonstrate that Tremain has done extensive research on the workings of the Foundling Hospital, its affiliated fostering system and the practice of stone-picking.

The novel is packed with treacly images and cliché. Consider, for instance: ‘She had no words anymore, only a feeling of sorrow and despair unlike anything she had ever known’; and ‘they clung together, crying and rocking to the rhythm of their broken hearts, until at last they were still and the nurse returned to snatch at Lily’s curls and pull her away by her hair’. Supposed seven-year-olds speak with a queasy maturity (‘It’s too painful for her’; ‘You’re meant to be sisters of mercy’). An eight-year-old hangs herself with a hand-knitted scarf 17ft long.

This is pulpy, mawkish pastiche veering on the penny dreadful, more Lemony Snicket than Charles Dickens. In what’s billed as a ‘tale of revenge’, the abuse that merits Lily’s crime is stuffed in at such speed it feels almost flippant, and the murder itself fails to hold the whole taut. Add to this a bizarre, para-paedophilic love plot and the result is a confused, disappointing novel.

Satire misfires: Our Country Friends, by Gary Shteyngart, reviewed

It is, as you’ve possibly noticed, a tricky time for old-school American liberals, now caught between increasingly extreme versions of their traditional right-wing adversaries and the new Puritans on the left. In Our Country Friends, Gary Shteyngart sets out to explore their resulting confusion — but ends up inadvertently exemplifying it.

Like his creator, the protagonist is a Russian Jew, born in Leningrad in 1972, who as a boy moved to America with his parents and later made his name writing satirical novels about people from the same background. Unlike Shteyngart, though, Sasha Senderovsky is now facing a stalled career, having abandoned literature in an ill-advised bid for success in TV screenplays.

Luckily, Sasha still has his house in the Hudson Valley, and the bungalows around it, that he bought in more prosperous times. He also has just about enough money (or, at least, access to credit) to invite four city-dwelling old friends to sit out the first Covid lockdown there with him and his family.

The three oldest friends are second-generation immigrants too: an Indian and two Koreans — one of them a woman called Karen who’s made millions from an app that makes couples fall in love. The other is his former student Dee, a polemical essayist doing her liberal best to defend the poor whites she grew up with against liberal attack. Both completing and unbalancing the group is a narcissistic film star, known only as ‘the Actor’, who’s come to ‘discuss’ (i.e. reject) Sasha’s latest script — and about whom all the women are soon fantasising.

As good liberals, these people try hard to feel guilty about living in some splendour while people are dying in the places they’ve left behind. The trouble is that they can never quite manage it. Instead, they eat and drink a lot, form sexual partnerships of varying plausibility and learn secrets about each other (not all terribly plausible either) that change their understanding of their shared past. In a book full of allusions to Chekhov, Karen’s app also serves as Chekhov’s gun — even if Shteyngart’s explanation of how it works remains distinctly baffling.

Not that they can completely stop what’s happening in the rest of the country from breaking in. There are, for example, plenty of pro-Trump mottos on local cars and houses. Less locally, a reference Dee once made to poor whites — Trump supporters included — as ‘my people’ leads to widespread accusations of racism on Twitter. And after George Floyd is killed, we get a particularly heartfelt passage in which Sasha wonders if America might be coming to resemble the Russia that it had once seemed such a refuge from. Or, worse still, that it had resembled it all along without him noticing, as he satirised the much easier targets of Russia and Russians with gloating vigour.

You might assume, then, that Shteyngart would now apply a similar vigour to the folks complacently partying in the Hudson Valley. Except that, like his characters, he can’t quite manage to walk the walk either. The Actor, of course, proves fair game. Yet, when it comes to what Shteyngart clearly regards as his people, he’s unable to shake off a sympathy that undermines the somewhat sporadic satire at every turn. He also supplies them with a far happier, even soppier ending than the novel would lead you to expect.

At times in fact, and despite the Chekhov references, the book that Our Country Friends brings most sharply to mind is The Wind in the Willows — in which the civilised, leisured main characters ultimately triumph over all those deplorable stoats and weasels.

How fears of popery led to a century of turmoil in ‘the land of fallen angels’

Stuart England did not do its anti-Catholicism by halves. In the late 1670s and early 1680s, a popular feature of London’s civic life were the annual Pope-burning pageants which took place every 17 November to commemorate the accession of Elizabeth I and the nation’s historic deliverance from the forces of international Catholicism. In 1679, one contemporary estimated that 200,000 people watched the spectacle, as a series of floats wound through London’s thronged streets bearing oversized effigies of Roman Catholic clergy, nuns, Jesuits and the Pope to be tipped into a bonfire at Temple Bar or Smithfield with lavish firework accompaniment. In some years, the Pope’s effigy would bow to the crowds, thanks to some elaborate stage mechanics; in 1677 it even screamed as it burned — in reality the sound of the cats imprisoned inside being consumed by the flames.

This brutal street theatre was one aspect of a period of political, religious and social turmoil known as the Exclusion Crisis, which centred on whether parliament could prevent the Roman Catholic Duke of York, brother of King Charles II and next in line to the throne, from ever succeeding to it. Clare Jackson’s absorbing new book demonstrates that, rather than simply being a local, historically specific phenomenon, the Exclusion Crisis was, along with other revolutionary moments and constitutional configurations, actually characteristic of an entire century in which Stuart England itself became a ‘synonym for instability’, especially when compared with Hanoverian Britain.

An effigy of the Pope ‘screamed’ as it burned – the sound of cats imprisoned inside being consumed by the flames

The ‘Devil-Land’ of her title is the name given to England during this tumultuous period by an anonymous Dutch pamphleteer who, writing in 1652, saw the nation as a land of fallen angels which had executed a Stuart monarch, Charles I, and replaced him with a republican government. Whereas the pamphleteer used the label to describe an anti-monarchical regime, Jackson uses it to track the turbulence and chaos long before (and long after) the English civil war and interregnum. She traces everything back to Elizabeth I’s execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, another Stuart put to death amid widespread fears of popery, which haunted successive administrations. Her study ends with an analysis of the Glorious Revolution and accession of William and Mary, whose Protestant credentials ultimately trumped James II’s hereditary rights.

One of the great strengths of the book lies in its compelling depiction of the centrality of foreign brokers to key events in early modern British history, whether that be the dynastic manoeuvrings of the Jacobean and Caroline courts, Charles II quietly taking bungs from Louis XIV in order to raise enough money not to have to bend to the will of parliament, or Dutch republican involvement in fomenting the unsuccessful Monmouth rebellion of 1685.

While such an account of events is familiar enough, Jackson’s great trick is to present the Stuarts themselves as aliens, invited south of the border to govern England amid fears of the expansionist designs of powerful Catholic neighbours. She gets past the xenophobic anti-Scottish sentiment in some English primary sources by focusing on ambassadorial reports to ascertain how foreign observers viewed this imported dynasty.

Even if envoys and ambassadors could occasionally provoke the ire of their hosts — ‘Good God! What damned lick-arses are here!’ opined one observer of countless sycophantic delegations to the Cromwellian protectorate — foreign correspondents allow us to view well-known figures and reputations from different, unexpected angles. For instance, such letters can show how Charles II and the Duke of York’s experience of European exile following the execution of their father expanded their horizons (as well as hardened their attitudes towards English parliaments). The Venetian resident in England, Francesco Giavarina, was shocked and impressed when they were able to conduct a meeting with him in Italian. Another dispatch from Aachen in August 1654, where Charles had gone with his sister Mary to view the relics of Charlemagne, depicted the future libertine king in a less sophisticated light; while Mary devoutly kissed Charlemagne’s skull, Charles grasped his sword and compared it with his own.

For all of the narrative drive and richness of this study, it is, however, compromised by one of its central contentions. Stuart England throughout this century, Jackson claims, was not just turbulent and revolutionary but actually ‘a failed state’, and was viewed as such ‘by contemporaries and foreigners alike’. However, what this book shows beyond question is that, for all of its profound regime changes — from monarchy to commonwealth to protectorate and back again — the quotidian business of government never stopped, economies continued to function and no foreign army was ever actually required to ensure the rule of law (even if foreign armies always lurked at the edges of fearful imaginations).

Momentous transformations such as the accession of James I, the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 and the arrival of William and Mary were all achieved without heavy losses of life. Even during those desperately bloody years of the English civil wars, there was a sitting parliament. And throughout the period of commonwealth and protectorate — while many might have railed against the different regimes’ legitimacy — the authorities were courted or feared by foreign powers as major players in European and global politics.

When it comes to Africa, the media look away

Kenya

We were flown around the country, hovering low over mobs using machetes to hack each other up

Each time I sit in St Bride’s on Fleet Street during the memorial of another friend, I look around at the crowds they’ve been able to pull in and feel terribly envious. Riffling through the order of service and then the church’s book of correspondents to find the faces of old comrades, I’m like a man wondering if any guests will bother turning up to one’s own hastily arranged bring-a-bottle party. Our 1990s generation of Nairobi hacks has been severely depleted. While we survivors are not a distillation of complete bastards, it’s natural to feel many of the best have gone before us. Too many were killed young on the story. In later years, the mundane explanations for colleagues’ deaths often seemed to hide the allostatic load and its delayed effects on mind and body. It was the impact of seeing too much for too long but also, of course, of living hard and fast and well and having far too much fun.

Mark Huband, who has just died at the age of 58, was a brave man and an excellent Africa correspondent. By the time he arrived in East Africa, he had already seen the horrors of Liberia’s civil war and he was pitched immediately into Somalia’s anarchy and famine. Personally we were never close and we both found it intensely irritating that many people mistook us for one another, especially given we were such different characters. Professionally we were rivals, but in the violent cauldron of Mogadishu we spent a great deal of time together, ducking into the same craters, taking notes in the same famine camps, and in the evenings sharing bottles and stealing each other’s cigarettes. Mark worked for the Guardian and I was a Reuters man. One of the hardest things about our task in Africa then, as now, was to get editors to take the story seriously. In Somalia during 1992 we reported on the violence, the rise of extremist Islam and the exodus of refugees heading for the West, hoping for intervention that would stem the chaos. But nobody gave a damn, it was hard to get a story in the foreign pages and look at the world today.

In April 1994 we all headed for Rwanda as the mass killings began. I joined a column of Tutsi guerrillas trekking south from the Uganda frontier to Kigali and the bodies were already piling up in the churches, clogging the rivers and stinking in the banana groves. Within days it became clear that things in Rwanda were getting very nasty, on a scale that even the Nairobi hacks had never witnessed. But it was still hard to persuade editors to run the story in the depth it deserved. After all, only a few months before, in the neighbouring Central African state of Burundi, our same group of correspondents had reported on the massacres of tens of thousands of Hutus. One day, the BBC correspondent Mark Doyle and I had somehow persuaded the assassinated president’s pilot to fly us in his helicopter around the pocket-sized country, hovering low over mobs of people using machetes to hack each other up. They didn’t even pause in the killings as we filmed them in the downwash of the chopper’s rotor blades — but our reports hardly made a blip or a blob in the world’s news during those days.

Now as the days and weeks passed, Rwanda did start to attract more international attention and it began to run above the fold. But Mark became deeply frustrated by the Guardian’s apparent refusal to give Rwanda enough space. He was aligned with his paper’s politics — many years later, in the UK’s 2019 elections, he stood as a Labour candidate against Jacob Rees-Mogg in Somerset — but his editors’ neglect incensed him. At the time, it seemed to us that the editors were frightened of covering the genocide in too much depth because they didn’t want a negative story to come out of sub-Saharan Africa during the very same month as Nelson Mandela’s inevitable election victory in South Africa. The view, we believed, was that newspaper readers could take only one story out of Africa at a time and the Guardian wanted it to be a happy one. Mark took the decision to resign from his paper in protest, an incredibly difficult one given that he now had nowhere to file to. But he stayed in the thick of the war and continued covering Rwanda’s bloodbath until the millions of refugees escaped across the frontier into Congo, where they then began dying in multitudes from cholera — and the next phase of Central Africa’s conflicts began. I always admired Mark after that and will remember him with great respect.

Bridge | 20 November 2021

The Champion’s Cup is an annual competition for the national champions from 12 European countries. As my team won the Premier League in 2019, two years later we found ourselves on the way to Pezinok in Slovakia to take on 11 other strong teams. My regular team mates Thor Erik Hoftaniska and Thomas Charlsen, playing for Norway, won the event on the last board and we missed the play-offs by 1VP! Typical! Italy fielded a squad without any of the big names, but the killer instinct is in their DNA, which makes them very dangerous. Just look at what they did against the favourites from Switzerland:

Tiziano Di Febo for Italy, in the South seat, might very well have considered passing out 3♥X with everyone vulnerable, but then it wouldn’t have been much of a story. Instead he responded 3♠, and now his partner, Lanfranco Vecchi, was unstoppable. Tiziano fought off a number of slam tries, but then sheepishly had to admit to having a third-round control in the club suit, and soon found himself in a grand slam where play was like walking a tightrope.

He ruffed the Heart lead and played A,K of Clubs and ruffed a Club high, West shedding a Diamond. He went back to dummy in Diamonds and ruffed another Club high, West again throwing a Diamond.

One round of trumps to dummy, and then two rounds of Diamonds ruffing with the 6, which held. All that was left now was to ruff a Heart low in the dummy and — when that also held — he could breathe again and put +2210 on the score card for a massive pick-up.

2530: Ups and downs – solution

The quotation is ‘LAUGH, AND THE WORLD LAUGHS WITH YOU; WEEP, AND YOU WEEP ALONE’ from Solitude by Ella Wheeler Wilcox. Her two unclued novels are SWEET DANGER (34/24) and A DOUBLE LIFE (3/29). ELLA (on the perimeter), WHEELER (12) and WILCOX (diagonally from 12) were to be shaded.

First prize Roy Sharp, Kelburn, Wellington, New Zealand

Runners-up Sue Topham, Elston, Notts Glyn Watkins, Portishead, Bristol

2533: Monday’s Child

A nine-word phrase (in five unclued lights, two used twice) opens a work for 1A (three words) by 8 (two words). The work inspired the other two unclued lights.

Across

9 A horse’s bridle eventually just as old (7, three words)

11 Outrageous, a chimney turning half black (7)

12 Army team endlessly tense in unofficial lodging (5)

14 US herb and Pacific salmon: can it (6)

16 Rich American left in terminal (5)

21 Are struggling with debt? Paid some back (7)

22 Various parts of body set to catch one’s glance (7, two words)

25 Consider material dangerously fiery (5)

31 Shortly taking over, finally tie the knot (7)

32 Stunned, a bit dry internally (7)

35 Left Germany shortly after noon (4)

36 Revolution almost engulfs European city (5)

38 Smacks small children (6)

39 Languish a bit, full of love (5)

40 Drama, digging out hard earth for shrub (7, two words)

41 Like spades as trumps initially? Much dislike holding these (7)

Down

1 Whistle softly and scatter loudly (4)

2 Throw over European social group (5)

3 Sound stopper is to make watertight (5)

4 Sound off in the bilingual tour? (6)

5 Licentious Burns’s memory is timeless (7)

6 One that cries, coming across large slaver (7)

7 A ticket seller is quarrelling in America (6, two words)

13 Notice two females, one in pain (7)

18 Master of camouflage caught in small picture at foot of page (10, two words)

19 Lapses that ruined product’s early trials (10, two words)

20 Ravenous retinue messily gobbling seconds (8)

23 Social worker has a lot of cash in both hands (7)

27 In royal house, hearts regularly that fall at one’s feet (7)

29 Warning of trouble, having a rising stomach (7)

30 Book is excellent: I am surprised (6)

31 On face spot difficult situation before greeting (6)

33 Speaking, supporters talk tediously (5)

34 At one stage insects put pressure on poisonous tree (5)

37 Carol, or her brother? (4)

A first prize of £30 for the first correct solution opened on 3 December. There are two runners-up prizes of £20. Please scan or photograph entries and email them (including the crossword number in the subject field) to crosswords@spectator.co.uk – the dictionary prize is not available. We will accept postal entries again at some point. Please note that because of the Christmas printing schedule the closing date is earlier than usual.

Dominic Raab’s ‘Nightmare Song’

In Competition No. 3225, you were invited to provide a version of the Lord Chancellor’s ‘Nightmare Song’ from Iolanthe for any member of the British cabinet.

Long Gilbertian lines mean there’s space only for me to applaud stellar contributions all round, but especially from D.A. Prince, Katie Mallett, Rachael Churchill, Janine Beacham, George Simmers and Bill Greenwell, who imagines what might rob the levelling–up secretary of his rest. Here’s a snippet:

When you’re lying awake and it feels like a snake Is adjusting your weak moral compass Then you groove to ‘Le Freak’ as an elderly geek Throwing shapes in an Aberdeen rumpus…

The winners below net £35 each.

When you’re lying awake and you shiver and shake, as you’ve done for the whole of the evening, And you can’t stand the fuss about you and Liz Truss over which of you ought to have Chevening, Well, you’re sleeping at last, but it proves a disaster, as nightmares begin to take over, And you have to admit to an MPs’ committee you didn’t know trade came through Dover. And now you’re in Calais, rehearsing a ballet, and putting your two best feet forward, But you stumble and cough and your tutu falls off and you’re savaged by Craig Revel Horwood; And a voice booms out ‘Raab! Have you had your tenth jab?’ and you’re trying to plead and to wheedle, But Vallance and Whitty, who don’t look too pretty, approach with a 20-foot needle; Then you fall in a trance, someone’s starting to dance: you! The Member for Walton and Esher, Now there’s nowhere to hide as you’re trans-mogrified to a mad fundamentalist preacher; And you’re stuck in Kabul in a prison that’s full, and the jailers are all trying to fleece you, And you’re starting to moan because no one will phone and demand that they’d better release you, But you’re tied to a post and they tell you you’re toast, and there’s no way you’re going to be leavin’, In your pink and green tights you demand human rights, (yes, the ones you’ve refused to believe in); And you’re feeling so numb as the Taliban come and condemn you for what you’ve been wearing, But you don’t give a fig, so you throw off your wig and awake with a shudder despairing… Nicholas Hodgson/Dominic Raab

When you’re lying awake, in need of a break and mopping your forehead with tissues, When you worry and fret and your mind is beset with a thousand intractable issues, When nothing turns up as the planet burns up and environment matters are pressing, And cheaper air fares only add to your cares in a budget that offers no blessing; When the populace sighs as food prices rise and the plight of the poor never ceases And asthma runs rife as you’re gasping for life while the carbon dioxide increases, When a Minister’s call is to please one and all and resolve each unsolvable riddle. How you long for the charm of life on a farm like your dad in his calm Cornish idyll. When laden and lumbered and always encumbered with onerous cabinet cares, And you ponder and brood on Environment, Food and intransigent Rural Affairs Not knowing at all if you’ll rise or you’ll fall as you can’t see the wood for the trees, Then the minister’s lot is most certainly not a ‘walk in the park’ or a ‘breeze’! So, tired and troubled, confused and befuddled with countless conundrums to fix, You’re unable to see what the outcome will be from the fallout of COP 26. But rising from bed with problems ahead, after dressing and shedding your nightwear, With all that’s in store, you know that for sure, the day will be more of a nightmare! Alan Millard/George Eustice

When you’re lying awake with a fiscal headache and a nightmare has tangled the bedsheets: All the columns were plus but a Routemaster bus had just driven a hole through your spreadsheets. Now you’re longing to snore but the people next door are engaged in protracted relations, so instead of some sheep you are counting the heap of the debts that we owe to all nations. But your calculus slips with the weight of the chips that the Wykehamist shoulders for Eton, for the don’t-give-a-toss of your dissolute boss leaves uxorious husbandry beaten. You’ve decided it’s cuts and with no ifs-or-buts when your dreams fall apart without warning as zoogamous howls and Churchillian growls tell the world and his wife that it’s morning. Nick MacKinnon/Rishi Sunak

When you’re lying awake, you’re in need of a break, So you search for the right destination: The venue’s unique and decidedly Greek, It would seem an idyllic location. By the Aegean Sea you can set yourself free Of the chattels of responsibility, So, ignoring the news, you have a short snooze, As you’re lulled in a state of tranquillity. Yet your sleep is invaded, you dream you’re downgraded With talk of an investigation, The voice in your ear makes you shudder with fear, There’ll be questions about your vacation. You’ll be toeing the line and you’ll have to resign — Yet the outcome is never so sinister, For when you awake, you’ve a slice of the cake, You’re deputy to the Prime Minister! Sylvia Fairley/Dominic Raab

No. 3228: small minded

You are invited to recast an extract from adult fiction (please specify source) rewritten for inclusion in an anthology of children’s literature. Please submit up to 150 words to lucy@spectator.co.uk by midday on 1 December.

No. 680

White to play and win. The conclusion of an endgame study by Henri Rinck. The imminent promotion of the g-pawn makes White’s situation look desperate, but there is one way to win the game. What is White’s winning move? Email answers to chess@spectator.co.uk by Monday 22 November. There is a prize of £20 for the first correct answer out of a hat. Please include a postal address.

Last week’s solution 1 Qxf6+! Kxf6 2 Rxh7 Rxc1+ 3 Nxc1 and Black cannot prevent both Rxf7# and Ng4#

Last week’s winner Willie Dong, Santa Cruz, California

Sacrificing the queen

One of the most eye-catching games from the recently concluded Fide Grand Swiss in Riga saw an early sacrifice of queen for knight, bishop and pawn. This exotic balance of material usually favours the queen, based on the rule of thumb that pawn = 1, knight = 3, bishop = 3, rook = 5, queen = 9. But when the minor pieces coordinate well, particularly with rooks alongside, they can be more than a match for the queen.

A queen’s greatest strength is her ability to attack, and perhaps fork, any pieces that are not nailed down. So when you jettison your queen for a miscellany of pieces, they had better resemble a florentine more than a fruit salad. It helps when the minor pieces have a clear target of their own.

That is the situation that occurred after 14 Be2 (see diagram 1). Black’s problem was that he had nothing to attack, and 14…Qg5 15 Be3 would only make things worse. 14…f5 was a bid to open up lines for the queen, but after Predke’s accurate response, it was Black’s king that came under fire.

Alexandr Predke–Nodirbek Yakubboev

Fide Grand Swiss, October 2021

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 Bg7 4 e4 d6 5 h3 O-O 6 Bg5 Nc6 7 Nf3 h6 8 Be3 e5 9 d5 Nd4 10 Nxd4 exd4 11 Qxd4! 11 Bxd4 allows a powerful riposte: Nxe4! Then 12 Nxe4 (or 12 Bxg7 Re8!) Qh4! wins back the piece. One pretty idea is 13 g4 Re8 14 Bg2 Bf5! 15 gxf5 Rxe4+ Ng4 12 hxg4! 12 Qd2 Nxe3 13 Qxe3 grants Black good compensation on the dark squares. Bxd4 13 Bxd4 Kh7 14 Be2 (see diagram 1 ) f5 15 exf5 gxf5 16 Rh5 Kg6 16…fxg4 17 Bd3+ is devastating 17 Kd2 fxg4 18 Rah1 Bf5 19 Rxh6+ Kf7 20 R1h5 Ke7 21 Nd1 After this elegant regrouping, the knight will be nicely anchored on e3, and the Bf5 is unmoored. c5 22 Bc3 Kd7 23 Ne3 Bb1 24 Bxg4+ Kc7 25 f3 Qe8 25…Bxa2 allows the rook in to h7: 26 Ba5+ b6 27 Rh7+ Kb8 28 Bc3 and Rh7-d7 is looming 26 Rh1 Bg6 27 Re1 Rg8 28 Be6 Qf8 29 Reh1 Re8 30 R1h4 Preparing 31 Bxg8 Qxg8 32 Rg4. Rxe6 31 dxe6 Qe8 32 Nd5+ Kc6 33 Nf6 Qe7 34 Rg4 Black resigns

Predke’s sacrifice reminded me of a beautiful game played by England’s John Nunn in 1977. In the diagram position, 12…Ngh5 13 Nxf6+ Nxf6 14 Qf3 would recover the piece. Instead, Nunn dealt with the pin in a more radical fashion.

Josef Augustin–John Nunn

European Team Championship, Moscow 1977

12… Nxd5 13 Bxd8 Nf4 14 Bg5 Nge6 15 Bxf4 Nxf4 White has no way to budge this mighty knight, and is soon overrun on the kingside. 16 Kh1 Be6 17 Bf3 Rh4 18 Rg1 Ke7 19 Rg2 Nxg2 20 Bxg2 Rah8 21 Qd2 Rxh2+ 22 Kg1 R2h4 23 Re1 Rg8 24 Re3 Bxe3 25 Qxe3 Bh3 26 Kf1 Bxg2+ 27 Ke2 c5 28 Qd2 b6 29 Qc3 Rgg4 30 Qa3 a5 31 Qb3 Bh3 32 f3 Rg2+ 33 Ke3 Bg4 34 fxg4 Rfxg4 and R4g3 mate. White resigns

The vaccine cheer is gone

I am 45, which means I’ve now had my third Covid vaccine. The experience of getting that injection crystallises a thought: Britain is starting to take the miracle of vaccination for granted, and that spells trouble for Boris Johnson.

I don’t use that word ‘miracle’ lightly. The development and distribution of working vaccines with such speed and scale is surely a historical event, and one that should give both big-state left-wingers and the free-market right pause for thought, since it relied on the partnership between public and private.

The politics of the vaccine have always been slightly under-appreciated in the Westminster village. The Hartlepool by-election, for instance, was undoubtedly another moment of historical importance, but I suspect future historians will give the vaccine effect more credit for the result than many contemporary accounts do.

Jabs gave Boris a bounce, but something that bounces up must eventually come down again

But enough about history. Let’s talk about me.

I got my third jab at the same GP surgery that did the first two, in March and May. That meant standing in the same queue with people drawn from the same cohort: 40-something residents of Tooting and Balham in south London.

Those first two visits were very cheery. After a grim winter of lockdowns and despair, who could fail to smile at the jab that might mean freedom and a return to some sort of normal? So queuing felt like the continuation of the Thank You NHS-clapping on the doorstep of the early pandemic. That meant smiles and effusive thanks for the volunteers and staff running the vaccination centre. And stickers: in what other circumstances would adults proudly sport ‘I’ve had my job’ stickers designed for kids?

This time, not so much. Maybe it was the damp and the cold, but the bonhomie was definitely gone. Instead of thanks there were mild grumbles about the queue, the lack of communication, and especially about the advice to wait at the surgery for 15 minutes after the injection in case of after-effects. There were no stickers, and I didn’t hear anyone ask for one.

I don’t want to overstate this or overinterpret it: it was one visit to one surgery. But I think that dissipation of gratitude and relief is also visible in the national mood and political debate. The vaccine programme just isn’t a thing any more. It’s become routine, something that can be taken for granted, much as that original industrial-scientific miracle is now a mundane part of our recent past. Jabs gave Boris a bounce, but something that bounces up must eventually come down again.

This is quite normal, of course — there is generally little gratitude in politics. Winners are usually politicians who tell the best story about the future, not the past, which is why it’s never wise to write off Boris Johnson, a chronic optimist and first-class storyteller.

For now though, the evaporation of that temporary gratitude is, I think, inadequately explored in current political conversation. Yes, the Prime Minister has made horrible and largely unforced errors over sleaze, and — more importantly — the cost of living is rising.

But an overlooked reason those things are hurting a politician who has previously looked invulnerable to mortal weapons is that the golden glow of the jabs miracle is wearing off. Vaccine efficacy wanes in more ways than one.

Nadine battles the BBC

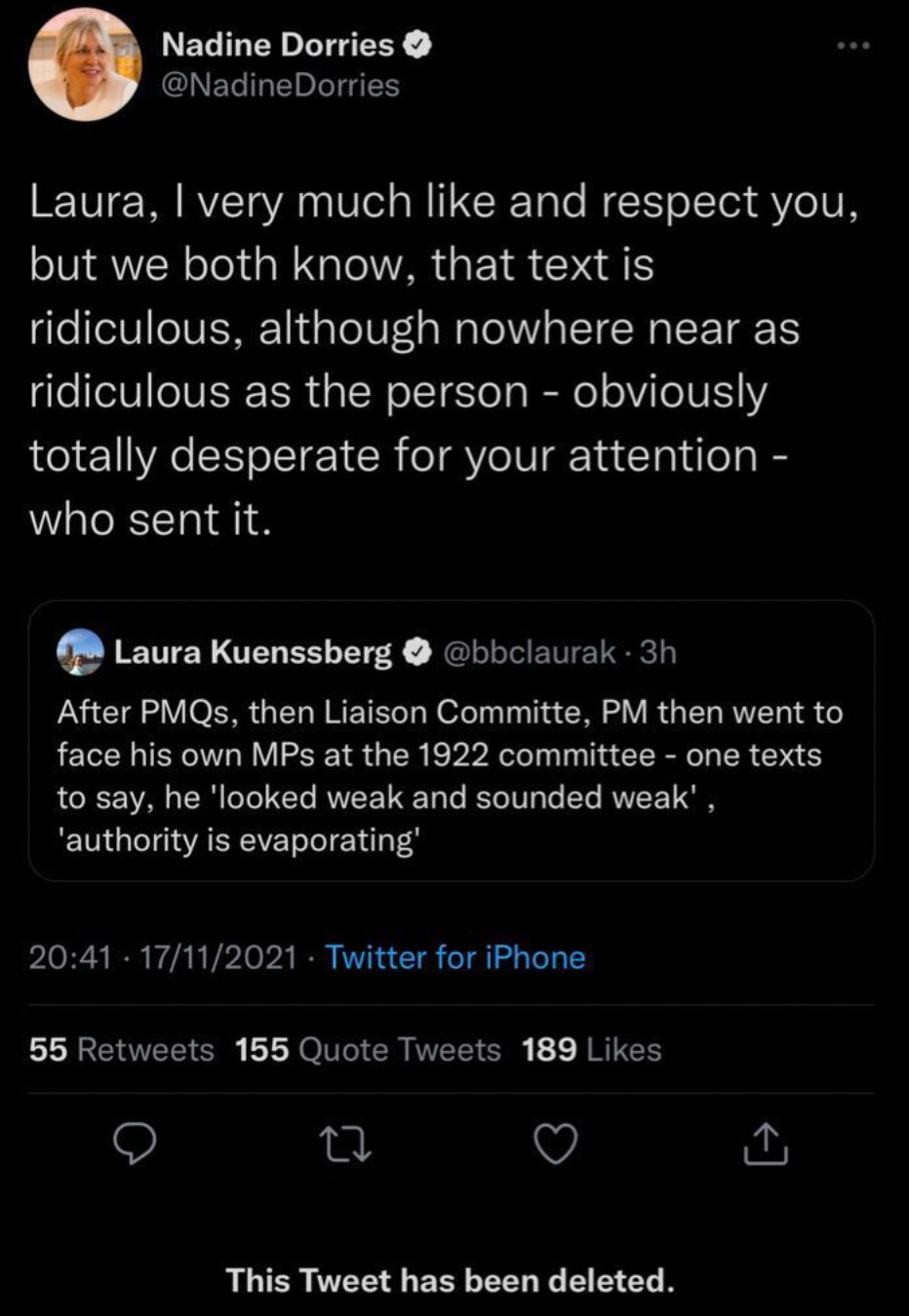

It seems that the fruits of high office haven’t changed Nadine Dorries. The Culture Secretary, who took up her brief eight weeks ago, last night hit out at Laura Kuenssberg on Twitter after the BBC’s political editor reported receiving a text from a Tory MP at the 1922 committee which said Boris Johnson ‘looked weak and sounded weak’ and that his ‘authority is evaporating.’ Dorries responded angrily, declaring:

Laura, I very much like and respect you, but we both know, that text is ridiculous, although nowhere near as ridiculous as the person – obviously totally desperate for your attention – who sent it.

Shortly thereafter the tweet was deleted but not before numerous screenshots went viral. Dorries is well-known as a vocal critic of the Beeb, once claiming that eating ostrich anus on I’m a Celebrity was ‘more pleasant than talking to [the BBC]’ and arguing that the broadcaster ‘excludes people from working class backgrounds.’ She also believes its current licence fee and ‘aggressive persecution’ of non-payers ‘would be more in keeping in a soviet style country,’ lambasted BBC management for providing ‘cover for despicable paedo Saville’ and dubbed the Corporation a ‘biased left wing organisation which is seriously failing in its political representation.’

Still, the Culture Secretary’s decision to attack a reporter’s coverage so directly has caused some considerable unease in Tory circles. While other MPs like Conservative backbencher Tom Hunt also ridiculed the claims cited in Kuenssberg’s tweet, Dorries has responsibility for the BBC in her remit, amid fears in both government and the government of another war of words between ministers and the state broadcaster. The intervention comes as the BBC are trying to appoint Kuenssberg’s successor amid some reports that the new hire will need to be ‘acceptable’ to No. 10.

Dorries’s intervention of course comes just a day after Health Secretary Sajid Javid urged a Twitter user to ‘show some respect for the NHS.’ Is this the start of a more bolshie Cabinet presence on social media? Sleaze, rows and now British beef going viral – it really is back to the nineties.