-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Labour MP ditched Birmingham bin strikes for Japan

Dear oh dear. As the Birmingham bin strikes rumble on and rubbish continues to pile high on the city’s streets, some of the area’s residents can’t get out of there quick enough – including the, um, MP for Birmingham Hodge Hill and Solihull North, Liam Byrne. The senior Labour politician has found himself in the spotlight after he was accused of abandoning his constituents by taking an extravagant trip to Japan during the crisis. Alright for some!

As revealed by the Mail, Byrne flew to Asia with seven other politicians on the business committee at the end of March. But at the same time the parliamentarian was enjoying his business class flight and five-star hotel stay in Tokyo, Birmingham’s bin workers were taking strike action – with uncollected rubbish piling up so quickly that the city council was forced to declare a major incident in the area three days after the MP left for Japan. To add insult to injury, it has even been suggested that Byrne may have extended his trip for a personal holiday – as he was not listed as one of the politicians with Friday as their departure day. The parliamentarian is now understood to have left the country – but a source close to him declined to give details of his movements since the Friday his colleagues flew home. How very curious.

It’s not the first time the business committee chair has come under fire for dereliction of duty. The politician has also been accused of being ‘missing in action’ during Donald Trump’s Liberation Day tariff drama, reportedly steering clear of a number of Commons hearings this week. And this is the same MP and former Treasury minister, Mr S would remind readers, who in 2010 left a note for his Conservative successor to inform them there was ‘no money’ left. Perhaps if Byrne spent less time enjoying himself on taxpayer-funded trips and more time with his constituents, he might find the cash will stretch a little further…

Is Britain really a nation of dog lovers?

Britain prides itself on being a nation of dog lovers – but is this true? Animal rights campaigners have targeted a leading dog show, accusing the event of promoting ‘deformed’ breeds such as pugs and bulldogs.

Peta wants the Scottish Kennel Club to disqualify brachycephalic dogs, which have shortened noses and flat faces. These dogs ‘can barely breathe — let alone go for a walk or chase a ball — without gasping for air due to their shortened airways,’ said the group.

This isn’t the first time campaigners have targeted dog shows: last month, Peta supporters were removed from Crufts in Birmingham after they complained that it’s cruel to breed dogs with very short legs, like dachshunds and corgis. These breeds, which Peta describes as ‘frankendogs’, can suffer lifelong back and knee pain because of their short legs.

Whether we love dogs or not, we certainly love buying them: between 2019 and 2022, the number of pet dogs in the UK surged from nine million to 13 million as the loneliness of lockdown made people want four-legged friends to keep them company.

But as the world opened up and the cost-of-living crisis set in, record numbers of dogs were dumped at sanctuaries, as some of these new owners decided they didn’t want them after all. They didn’t realise that a dog is for life, not just for Covid.

A lot of these dogs were dumped in a bad way: the BBC has reported that dogs arriving at rescue centres since the pandemic have a higher incidence of health and behavioural problems.

Dogs used in racing don’t get much love either. Greyhounds are often muzzled and kept in lonely cages for up to 23 hours a day. During races, they can suffer broken legs, heat stroke, and heart attacks.

In 2006, the Sunday Times revealed that a builder had killed over 10,000 racing greyhounds with a bolt gun and buried them in a mass grave. The episode was described as ‘canine killing fields’ and people were very angry but not many in this nation of dog lovers stood up and demanded the end of such a cruel ‘sport’.

Between 2018 and 2023, some 3,145 racing greyhounds died, including dogs dying on the tracks or being killed because they were no longer fast or healthy enough to make enough money for their owners.

And did you know that dogs are still used for experiments in British labs? In Cambridgeshire, a controversial American company called Marshall BioResources breeds thousands of beagles each year and sells them to laboratories. Home Office statistics show that in 2020, there were 4,320 procedures carried out on dogs – 4,270 procedures on beagles specifically. Footage secretly filmed at the Cambridgeshire breeding site showed beagles confined to cages and displaying signs of extreme stress. The company insists it’s ‘dedicated to maintaining high standards of animal welfare’.

I wonder if we really love dogs, or if we just love how they make us feel. It’s easy to love a cute puppy but when a dog really needs love a lot of owners go missing. Asked what the hardest part of his job was, a vet said it was when he had to put an animal to sleep. He explained that 90 per cent of owners refuse to be in the room when he injects their pets, so the dog’s ‘last moments’ are ‘usually them frantically looking around for their owners’.

Don’t expect much from Wes Streeting’s waiting list purge

Well, that’s one way to reduce NHS waiting lists: to kick off a load of patients whom you have decided don’t need to be on them. New NHS chief executive John Mackey has ordered that everyone on a waiting list must be ‘validated’ – with the aim of removing 300,000 of the 7.43 million names on them. Examples given are people who have already been seen privately and have no further need for NHS treatment, people who have instead sought help in A&E, people who no longer have symptoms or those who could be seen ‘in the community’ instead (i.e. at GP surgeries or clinics).

Many of the names which have been removed will have been a symptom of failure

I don’t doubt that there are people on NHS waiting lists who don’t need to be there. I have had experience myself of what have been termed ‘pointless appointments’. A few years ago I had a wart removed. My GP didn’t manage to do it, so he referred me to the local hospital. I thought the procedure was going to be performed on the spot, but no, that was just to line me up for treatment. When, several months later, my wart finally was excised, it took all of two minutes, leaving my inner time and motion man to ask: why couldn’t it have been done on the first occasion? A needless NHS waiting list had been created when it didn’t need to exist.

Yet it isn’t hard to see what is going to happen as a result of this review. The government will claim success at reducing NHS waiting lists when many of the names which have been removed will have been a symptom of failure. Just look at the list of people who are going to be purged. Take the patients who no longer need NHS care because they have been seen privately. No prizes for guessing why they ended up being seen privately: they were fed up of sitting on a waiting list. Or people who have sought help in A&E instead. Why did they end up having to do that? Again, it is likely that their condition deteriorated while they were languishing on a waiting list. We can be pretty sure that there will be people sitting on waiting lists who are actually deceased – but funny enough, the NHS has not cited them as candidates for the purge.

Removing all these names might look like a triumph because technically waiting lists will be shorter, but it won’t make any difference to the time it takes to receive treatment. People who are sitting on waiting lists but who have already been treated privately or who have been seen in A&E don’t really hold up treatment for others because they are not going to take up any clinical time – their names will end up getting struck out at the point they are finally allotted an appointment.

There is, on the other hand, no doubt scope to make a genuinely useful contribution to reducing hospital waiting lists by treating people in the community instead. But the great waiting list purge has echoes of Tony Blair’s day, when the NHS was so driven by targets that it ended up creating perverse outcomes. A target for reducing A&E waiting times, for example, resulted in people being taken from waiting rooms, looked up and down and then dumped in a corridor before they were eventually seen properly. Look, boasted the government, hardly anyone has to wait in A&E for more than four hours. Yet the reality was somewhat different. Don’t expect too much from Wes Streeting’s great waiting list purge, either.

Watch: Badenoch blasts Beeb over Adolescence questions

The progressive class’s obsession with Adolescence continues – and Tory leader Kemi Badenoch is having none of it. When Badenoch appeared on BBC Breakfast this morning to discuss her party’s local election campaigns, presenters were quick to quiz the parliamentarian on her thoughts on the Netflix series, which has been lauded by Labour MPs – including the Prime Minister himself – for highlighting the perils of toxic masculinity. But the Conservative leader was quick to dress down her interviewers for their preoccupation with the, er, fictional show…

While Sir Keir Starmer praised Netflix bosses earlier this month for making the drama free to watch in high schools, the Conservative party leader admitted on LBC she had not watched it – before issuing a warning about ‘creating policy on a work of fiction’. But it appears her claim to be uninterested in the show was met with disbelief – as Badenoch was grilled once again this morning by the Beeb’s Charlie Stayt and Naga Munchetty about whether she had finally got around to watching the series. ‘No I haven’t,’ Badenoch responded firmly, going on:

KB: I probably won’t. It’s a film on Netflix, and most of my time right now is spent visiting the country.

NM: It is prompting conversations about toxic masculinity, smartphone use, young men feeling that they’re being ignored, the idea of misogyny being increased in school. Why would you not want to know what people are talking about?

KB: I think that those are all important issues, and those are issues that I’ve been talking about for a long time. But in the same way that I don’t need to watch Casualty to know what’s going on in the NHS, I don’t need to watch a specific Netflix drama to understand what’s going on.

Yikes. That’s them told! Watch the clip here:

Trump’s tariff pause has given Japan time to plan its next move

Asian markets are rebounding after President Trump announced a 90-day ‘pause’ in the implementation of the ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs that had sent shock waves through the financial community. Most dizzying perhaps were events in Japan, where after a vertiginous plunge on Monday, the Nikkei surged over 8.5 per cent on this morning’s trading. Japan’s iconic companies had a good day: Toyota was up 6 per cent, Sony 12 per cent and Mitsubishi 10 per cent. Elsewhere in Asia, the South Korean KOSPI rose 6 per cent, the Hang Sang climbed 2.69 per cent, the Singapore Composite Index 1.29 per cent and Taiwan’s stock exchange was up over 9 per cent.

It is worth noting, amidst the audible sighs of relief, that the suspension applies only to the ‘reciprocal tariffs’ (in Japan’s case 24 per cent, in South Korea 25 per cent) and that the 10 per cent base line which came into effect on Saturday remains. The new auto parts tariffs are still set to be implemented on 3 May, though Tokyo in particular is pushing for a rethink on those, and the global car tariffs too.

Trump does seem to have been impressed by Japan’s willingness to engage and compromise

Coming out of all of this rather well is Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba. The last week has been a masterclass in Japanese tact and strategic understatement. The initial announcement of the tariffs was described as ‘regrettable’ and ‘hard to understand’ by Ishiba, while last night’s dramatic reprieve was met with an almost comically mild response. ‘We take the recent announcement by the US government in a positive light,’ said chief cabinet secretary Yoshimasa Hayashi.

There were pledges of a ‘rational’ response and a complete avoidance of intemperate or potentially aggravating language and no talk of retaliation – though it was never clear how that could have worked anyway. Ishiba moved quickly and apparently urged Trump to rethink his tariff policy in a reportedly ‘polite’ phone call on Monday.

Did it have any effect? Trump does seem to have been impressed by Japan’s willingness to engage and compromise and purred as he referenced the ‘top team’ Ishiba was despatching to Washington for trade negotiations. He may at least have been grateful to Japan for offering a response (which included the proposition of a wide-ranging recalibration of the US-Japan business and security relationship) which could be cited as an example for others to follow.

However, far more likely than Trump being influenced by Ishiba’s urgings, is that the US president has reacted to the panic in the American domestic economy and the surge in bond yields. The White House has sent out mixed messages, with Trump himself at one point admitting the pause was a reaction to ‘people getting a little bit afraid’. This was an explanation later contradicted by Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, who claimed that the pause had been the plan all along and time was needed to negotiate with the stampede of petitioning nations supposedly begging to reset their trading arrangements with the US.

All eyes will now be on the US-China showdown with the 125 per cent tariff rate remaining in place. China has been uncompromising in its response so far, adding 50 per cent to an already existing 34 per cent rate on US products starting from today. Trump says he is waiting for a call from Xi Jinping, but the latest word from Beijing is that there will be no climb down. Things have escalated to such an extent (China has said it would fight ‘provocations’ ‘to the end’) that any movement from either side would be unspinnable, involving a substantial loss of face, a highly significant factor in Asian culture – and, of course, Trump culture.

It will be interesting to see how the clear divergence between China and the rest of Asia affects the geopolitics of the region. There had been a gradual thaw in relations between Japan, China and South Korea in the last year as the three explored ways of improving supply chain cooperation and export controls. The trade ministers of the three countries met on 30 March ahead of ‘Liberation Day’ – their first economic dialogue in five years. Talks appeared to go well; and there were even rumours (from China – denied by South Korea and Japan) of coordinated retaliation against the Trump tariffs.

If that were ever true, the idea was quickly ditched and China now stands alone in direct opposition to the US. Japan and South Korea can lick their wounds and try to figure out what lessons can be learnt from the events of the last week and perhaps how they can better prepare themselves for what comes next.

In neither case will that be easy, though. Apart from the inevitable economic fallout out of the US-China confrontation, both South Korea and Japan face elections (presidential in the former case and upper house in the latter) in the next few months.

For Japan though, the uncertainty and instability of recent days may prove beneficial to the incumbent Ishiba. He had looked a goner after his snap election last October backfired spectacularly. Through his deft handling of the tariff issue, his odds of survival have somewhat improved.

Why the AfD is leading in the polls

Germany has a new government. It may also have a new government in waiting. On the same day that the centre-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and centre-left Social Democratic party (SPD) announced they had concluded coalition talks to form a government, a poll showed the hard-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) is the most popular party in Germany. A quarter of all voters now support the AfD. Since the election in February, the CDU has lost 5 per cent of its support.

It’s easy to see where it all went wrong for the CDU. Having promised fiscal responsibility, moderate right-wing governance, and the return of controlled borders, the party has instead rolled into bed with the SPD. Somewhat sneakily, the old parliament was recalled after the election in order to pass a giant debt package that lowered the ‘debt brake’, which is seen as protecting taxpayers from yet more government over-spending. The new parliament would never have supported such a move.

In return for lowering the debt brake, the CDU has had to give the SPD seven ministries, including the Ministry of Finance. They’ve also agreed to a €15 minimum wage and rent freezes. Not bad for the SPD, which only won 16 per cent of the vote. To win over the Greens, the CDU have said that another €100 billion will be spent on climate change, while reaching net zero by 2045 has been put into the German constitution. As you need a two thirds supermajority to change the constitution, there seems little chance that pledge will be removed.

Add in Trump’s tariffs, ever-rising taxes, and high energy prices and you have a recipe for yet more lay-offs and bankruptcies. German’s export model looks increasingly fragile and as Boomers increasingly retire, social spending is bound to rise.

Nor does it help that it remains far too easy to get German citizenship. Even though the coalition agreement includes abolishing the three-year long ‘turbo naturalisation’ process, immigrants can still get citizenship after only five years rather than the eight years it used to take. As it is mostly low-skilled migrants or asylum seekers moving to Germany at the moment, that means the state will be taking on an even greater benefits and pension burden.

Unsurprisingly, the German public are upset. Not only has the CDU dropped below the AfD in the polls but their leader Friedrich Merz is considered untrustworthy by 70 per cent of people. Merz has responded by saying that he won’t take criticism from the ‘far-right’, telling those worried by the polls ‘not to stare like a rabbit at a snake’. That may be enough for the party leadership and their members in parliament but the CDU grassroots are increasingly upset.

They have good reason to be. When the CDU dared to vote with the AfD in the last parliament, they faced a wave of outrage from the media and protest groups, many of which had state funding and links to left-wing parties. After the election, the CDU tabled 551 questions into state funding of these murky NGOs, only to withdraw them so they could form a coalition with the SPD. Rather than find out how much taxpayer money was spent on those who blockaded the CDU HQ in Berlin or the antifa who occupied some of their offices, they are going to give another €180 million to likes of ‘Living Democracy’. No wonder that even pro-CDU voices are saying the party has chosen to lose the culture war.

All of this explains why the party has been losing ground to the AfD in the polls. But rather than responding to the concerns of voters, the CDU and German society have instead embarked on a witch-hunt against those who support the AfD.

Normally the oldest member of the Bundestag becomes ‘senior president’. This should have been Dr Alexander Gauland, who was a member of the CDU for 40 years. But because he now belongs to the AfD, and to prevent him from giving a speech at the opening of the Bundestag, the CDU changed the rules to give the position to the far-left Dr Gregor Gysi.

Germany has become hysterical about the AfD. The party is banned from participating in the parliamentary football team ‘FC Bundestag’, despite winning a court case over the matter. The editor-in-chief of a pro-AfD paper was given a seven-month suspended sentence and fined for posting a meme jokingly showing the old interior minister holding a sign reading ‘I hate freedom of speech’. In Bavaria an altar boy was dismissed by his priest after taking a selfie with the controversial but charismatic AfD politician Maximilian Krah.

The coalition agreement between the CDU and SPD calls for lying to be banned in Germany. Perhaps the CDU should therefore reflect on their own broken promises to voters. So long as they keep giving in to the left, they will continue to sink in the polls. Meanwhile the AfD will benefit from being in opposition, as it waits for this coalition to become so unpopular that it collapses. The AfD may not be in government yet – but it seems only a matter of time.

The BBC is right to restore this paedophile’s sculpture

The BBC is once again at the centre of criticism – this time for spending more than £500,000 in restoring the vandalised sculpture of Ariel and Prospero from Shakespeare’s play The Tempest, that adorns the entrance to its London headquarters Broadcasting House.

The statue was sculpted in 1931 by Eric Gill, rightly described today by both the Daily Telegraph and the Guardian as ‘a paedophile’ who not only sexually abused his two daughters and his sister – but had illicit relations with the family dog as well.

But along with his sexual deviance, Gill was arguably the greatest British sculptor of the 20th century, whose name lives on in the Gill Sans typeface font that he designed in 1928. A fervent Roman Catholic, he is also renowned for sculpting the Stations of the Cross in Westminster Cathedral. His hidden life of incest and bestiality was first revealed by his biographer Fiona MacCarthy in 1989, using Gill’s own diaries in which he confessed to his secret perversions.

Since then, Gill has been posthumously targeted by anti-abuse campaigners who say he should be cancelled and his work covered up or destroyed because of his offensive secret life. In 2022, the Ariel statue was attacked by a campaigner with a hammer, watched by Police who did nothing to stop the hour long attack. In 2023, it was attacked with a hammer again.

In a statement explaining their decision to restore the statue behind a protective vandal proof screen, the BBC said that in doing so they were not condoning Gill’s abusive behaviour to his family. The whole affair raises anew the age-old question of whether an artist’s questionable personal life can or should be separated from their work.

Very few artists have led private lives of unblemished moral probity, and some have been positively criminal. The great Italian masters Caravaggio and Cellini, for example, are both believed to have killed men in brawls, and the early 20th century Austrian expressionist artist Egon Schiele was briefly jailed for allowing underage girls to see his erotic paintings, with the judge burning one of his depictions of a very young girl. Yet the works of all three are worth millions today, and no one has yet suggested that they should be cancelled. If the only works displayed in galleries were by morally upstanding artists living virtuous lives, they would be practically empty.

Gill was undoubtedly an eccentric figure who flouted respectable social standards in his own lifetime. He favoured dressing in loose smocks with no undergarments, and people passing in and out of Broadcasting House while he was working on Ariel would have received something of a shock and seen more than they bargained for, had they happened to glance upwards.

Some authorities have already succumbed to the anti-Gill campaign. In my home town of Chichester a blue plaque marking the site of Gill’s childhood home, was removed on the orders of West Sussex County Council in 2022.

Others have so far stood firm: I used to live opposite Gill’s birthplace in Hamilton Road, Brighton, and when last I looked, the plaque recording his arrival there was still in place.

In making a clear distinction between a great artist’s works and his shabby private habits, for once the BBC has done the right thing.

Lily Phillips isn’t an authority on sex

I wasn’t intending to write about Lily Phillips again. Her story would ideally be ignored. But if it does appear in the media, we must be vigilant about how it is represented, especially if the BBC is doing the representing. On some issues, neutrality is a bogus aspiration. It means allowing a very dubious narrative to stand, because contesting it would be awkward.

I am talking about Newsnight’s interview with Phillips this week, and the studio debate that followed it. Victoria Derbyshire, whom I generally rate highly, failed to challenge Lily Phillips in any serious way. Instead she allowed her to present herself as an authority on sex. She asked her, at length, about her early exposure to pornography, and noted that such exposure was common in her generation. This implied that Philips was a sort of spokesperson for her generation. ‘Sex is a part of life’, said Phillips at one point – Derbyshire should have asked her what she meant by ‘sex’. Then she distanced herself from extreme pornography, saying that she had ‘normal sex’ with guys. This too should have been challenged. Her final comment was this: ‘I think there’s always been women like me who have sex – the difference is that we talk about it online, we’re open about it.’ This too should have been contested – what on earth did she mean by ‘women who have sex’? Instead, those were the last words of the interview.

Then Derbyshire was joined by the journalist Sarah Ditum and Reed Amber, a sex-worker. Amber immediately came out with this: ‘I love the fact that [Lily Phillips] was saying that lots and lots of women across the globe also enjoy sex – I think that we have a really negative spin on the way we see sex – there’s a lot of stigma around not only sex but people who enjoy sex, and also people who enjoy sex for money.’ Ditum contested this pretty effectively: ‘I think there’s a really important difference between talking about female sexuality and talking about commercialised sexuality – they are very, very different things, and I think it is a mistake to parcel them together as the same thing.’ Spot on – but she should have been blunter. Her fellow-guest seemed not to understand the point, and maybe half the audience missed it too.

Let me put it bluntly, then. Sex-workers who claim to speak for modern liberated females should be sternly rebuked. They have an eccentric idea of sex, to put it politely. When a sex worker says that sex is a healthy desire, not something to be prudish about, we should respond like this: ‘No, no, no. You do not have the right to speak about sex, as it is generally understood. What you do, making money from your body, whether you charge people for having sex with you or for watching, is not sex as it is generally understood. It is a weird offshoot of it. Sex, for almost all of us, is rooted in committed relationships, and the serious slow business of psychological intimacy. If you by-pass these roots you are not qualified to speak about sex in the full sense.’

Donald Trump has got what he wanted

Donald Trump has peered into the abyss. The US President watched the Wall Street meltdown and the global trading system (from which America benefits as much as anyone) start to collapse, and he hit pause. The conventional narrative will be that Trump has blinked, but I think he simply got what he wanted.

Yesterday’s decision to put a 90-day pause on reciprocal tariffs, while increasing the rate on China to 125 per cent, has certainly come as a relief to the markets. The S&P500 was up almost 9 per cent on the news. Investors can breathe again.

It would be easy to argue that President Trump has simply chickened out of the fight. The tariffs were about to trigger a global recession, and the fallout from that would dominate the rest of his time in the White House. It is not worth it.

And yet that ignores an obvious point. The rest of the world has been terrified into submission. Over the next three months will see a series of concessions. Countries in Asia such as Vietnam that were about to be wiped out will welcome American goods. The EU will realise that Ford pick-up trucks don’t need any levies on them. Heck, even the British Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer may be photographed tucking into chlorinated chicken as he opens up the UK market. Trump will have won.

All this may well end with a global agreement to reorder trade and finance: the ‘Mar-a-Lago accord’ that had been rumoured in the markets for weeks. We will see over the next few weeks. True the uncertainty will linger for months and that will damage confidence. In the meantime, however, the crisis has been averted – and global trade can stagger on.

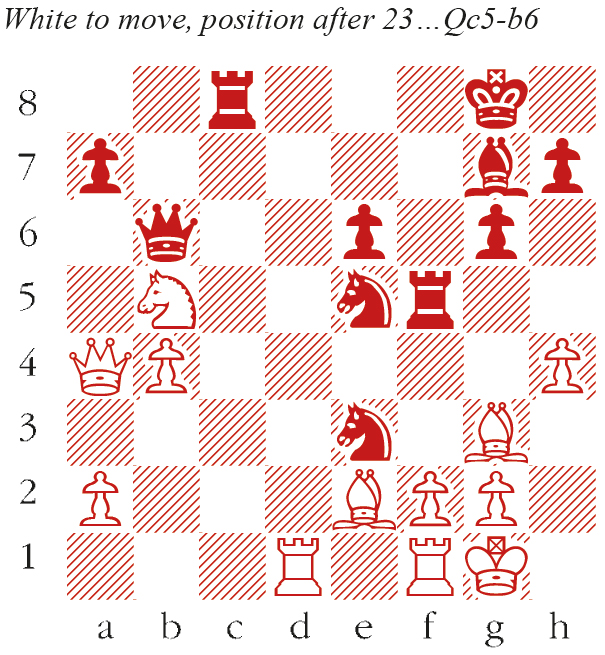

Fide Women’s Grand Prix

I like tournaments which award prizes for the best game, offering a welcome reminder that there is more to chess than points on the scoreboard. Naturally, who wins those is a subjective matter, and even what you call the award is up for debate. Should it be a ‘best game’ prize, in the sense of high-quality play with few mistakes? A brilliancy prize for a quick attack? Perhaps a beauty prize, for the game’s visual impact?

At the end of the Fide Women’s Grand Prix held in Monaco in February, a beauty prize was awarded for the game below. The former women’s world champion Alexandra Kosteniuk won a Cartier watch, much to the displeasure of Kateryna Lagno, who considered her own win against Elisabeth Pähtz to be the more deserving, describing it as one of the best games of her career. Lagno decried the judges’ decision as politically motivated, claiming that they would not award the prize to a Russian player. Lagno has represented Russia for many years, though she competes in Fide’s world championship cycle under the international flag, since Russia and Belarus were sanctioned by the governing body. Kosteniuk, once her teammate in the Russian women’s team, switched her federation to Switzerland in 2023.

Lagno’s game is well worth a look, even if her claim was doubtful: spectator.co.uk/lagno.

In the prize-winning game below, Tan Zhongyi grabs the initiative with a pawn sacrifice in the opening. But once it peters out, her attempt to reignite the game with 20…b7-b5 and later 22…Ng4-e3 is too ambitious, meeting a sharply calculated refutation from Kosteniuk beginning with 24 Nb5-d6. Once the dust has settled 15 moves later, the rest is a matter of technique.

The reigning women’s world champion, Ju Wenjun, is currently defending her title in a match in China against Tan Zhongyi. The 12-game match runs up until 20 April, with a possible rapid tiebreak on the following day.

Alexandra Kosteniuk-Tan Zhongyi

Fide Women’s Grand Prix, Monaco, Feb 2025

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 d5 4 Nf3 Bg7 5 h4 dxc4 6 e4 c5 7 d5 Bg4 8 Qa4+ Bd7 9 Qxc4 O-O 10 Qxc5 e6 11 dxe6 Bxe6 12 Ng5 Nc6 13 Bf4 Ng4 14 e5 Ncxe5 15 Rd1 Qe8 16 Nxe6 fxe6 17 Bg3 Rc8 18 Qb5 Qe7 19 Be2 Rf5 20 Qa4 b5 21 Nxb5 Qc5 22 O-O Ne3 23 b4 Qb6

24 Nd6! This counter-fork, the key move of the game, is by far the strongest response. 24…Nxf1 25 Nxc8 Nxg3 26 Nxb6 Nxe2+ 27 Kf1 Ng3+ 28 Kg1 Ne2+ 29 Kf1 Correctly walking into further checks. 29 Kh1 looks safe, but 29…h5!! creates a bolthole on h7 in anticipation of Qa4-e8+, and the various ideas of …Rf4, …Rxf2, …Ng4 and …axb6 give Black excellent chances to save the game. 29…Ng3+ 30 Ke1 Nf3+ 31 gxf3 Bc3+ 32 Rd2 axb6 33 Qe8+ 33 fxg3 would also win, though 33…Rd5 offers some resistance. 33…Kg7 34 Qe7+ Rf7 35 Qxe6 Nf5 36 Kd1 Bxd2 37 Kxd2 Rf6 38 Qe4 Rd6+ 39 Kc1 Kf6 40 a4 Rd4 41 Qc6+ Rd6 42 Qc7 Ke6 43 Qxh7 Ne7 44 h5 gxh5 45 Qxh5 Nd5 46 Qg4+ Ke7 47 Qe4+ Kd7 48 f4 Kc7 49 Kb2 Nf6 50 Qe7+ Nd7 51 Kc3 Rf6 52 Qe4 Rd6 53 Kc4 Rc6+ 54 Kb5 Rd6 55 a5 bxa5 56 bxa5 Rf6 57 Qc4+ Kb8 58 a6 Rb6+ 59 Ka5 Rb1 60 Qd4 Kc7 61 a7 Nb6 62 Qxb6+ A neat finish, although many moves suffice for the win. Rxb6 63 a8=N+ Kd6 64 Nxb6 Ke6 65 Kb5 Black resigns

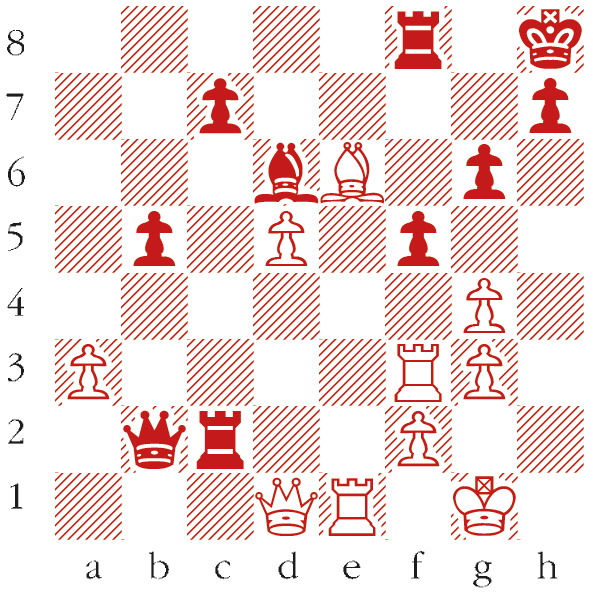

No. 845

White to play. Bjerre-Bodrogi, European Individual Championship, 2025. The game was eventually drawn, but in this position Bjerre missed a beautiful winning move. What was it? Email answers to chess@spectator.co.uk by Monday 14 April. There is a prize of £20 for the first correct answer out of a hat. Please include a postal address and allow six weeks for prize delivery.

Last week’s solution 1 Rf8+ Bxf8 2 Nf6+ Kh8 3 Qh7 mate

Last week’s winner Samantha Morgan, Rayleigh, Essex

Spectator Competition: Vernal triolet

For Competition 3394 you were invited to submit a vernal triolet.

In 1894, the poet Banjo Paterson wrote a heartfelt triolet in dispraise of the triolet and Brian Allgar did the same this week:

I really hate the triolet,

And, Spring or not, I find them hell.

‘Oh, tra-la-la, it’s cold and wet.’

I really hate the triolet.

All those repeated lines that get

Nowhere (just like the villanelle).

I really hate the triolet,

And, Spring or not, I find them hell.

Nonetheless, you rose to the challenge with gusto, producing a funny and poignant entry that was hard to whittle down to a winning line-up. Hats off to unlucky losers Tom Adam, Martin Parker, Iain Morley, Jasmine Jones, Alan Bradnam, Dorothy Pope, Nick Syrett, Bob Newman, Anna Cox and Susan McLean. Those below snaffle the £25 John Lewis vouchers.

Our snowman is a thing of woe,

A pile of coals is all that’s left,

He’s gone where melted crystals go,

Our snowman is a thing of woe.

Spring’s warmth has dealt a mortal blow;

Strange how it feels an act of theft.

Our snowman is a thing of woe,

A pile of coals is all that’s left.

Janine Beacham

Along the verge the daffs are out,

But sigh and have another vape.

Thrilling to see the green shoots sprout.

Along the verge the daffs are out,

Augurs of Spring without a doubt;

The human world is in bad shape.

Along the verge the daffs are out,

But sigh and have another vape.

Basil Ransome-Davies

Cruel spring, tell youth your lovely lies

Of greenery and resurrection

And happiness that never dies.

Cruel spring, tell youth your lovely lies.

Hide winter from their wishful eyes

And blind them with your false affection.

Cruel spring, tell youth your lovely lies

Of greenery and resurrection.

Frank McDonald

Sore eyes, runny nose and the impulse to sneeze,

these are the torments I suffer each spring,

It’s the pollen that spawns, as it wafts on the breeze,

sore eyes, runny nose and the impulse to sneeze,

though it may be like nectar to numerous bees

to me there’s the spectre of what it will bring:

sore eyes, runny nose and the impulse to sneeze,

these are the torments I suffer each spring.

Sylvia Fairley

Poets: they’re so excited over Spring –

all Oh-to-be-in-England, daffodils

and burgeoning when Love can have its fling.

Poets — they’re so excited over Spring

and yet it comes round every year, that thing

with birds and bees. It’s how they get their thrills,

poets. They’re so excited over Spring –

all Oh-to-be-in-England, daffodils.

D.A. Prince

It’s Spring! The sunlight’s in the mood;

The garden really won’t relax –

It can’t be still, it’s keen to brood.

It’s Spring! The sunlight’s in the mood

To breed a weed, to grow some food.

I pay new rates of Council Tax,

It’s Spring, it’s sunlight. In the mood?

The garden really won’t … Relax!

Bill Greenwell

‘Jug-jug, pee-wit, tu-witta-wu,’

These blasted birds are always singing.

Are there no other ways to woo?

‘Jug-jug, pee-wit, tu-witta-wu,’

Are not the sounds that I or you

Would choose to make when love is springing.

‘Jug-jug, pee-wit, tu-witta-wu,’

These blasted birds are always singing.

Gail White

The cuckoo’s call is quite unique –

It tells us all that spring is here.

Two notes announce her slick technique,

The cuckoo’s call is quite unique;

She has no shame, a wicked beak,

That ousts another’s eggs each year.

The cuckoo’s call is quite unique –

It tells us all that spring is here.

Elizabeth Kay

When May be out we cast a clout

And wear a shirt against the skin.

It’s pleasant when the sun is out

When May be out we cast a clout

Enjoy the sun and lark about;

Then shiver when the sun goes in.

When May be out we cast a clout

And wear a shirt against the skin.

Philip Roe

When little lambs come out to play,

it means that Spring’s begun its course.

Daffodils greet each brightened day

when little lambs come out to play.

While other lambs, from far away,

are silenced now. I serve mint sauce.

When little lambs come out to play,

it means that Spring’s begun its course.

Tracy Davidson

Oh, to be in Devon

Now that Spring is here,

Where it blows a gale force seven –

Oh to be in Devon,

Where it’s pissing down from Heaven

As though the End is near –

Oh, to be in Devon

Now that Spring is here!

David Silverman

No. 3397: In out, in out

You are invited to recast the ‘Hokey-Cokey’ in the style of a poet of your choice. Please email entries to competition@spectator.co.uk by midday on 23 April.

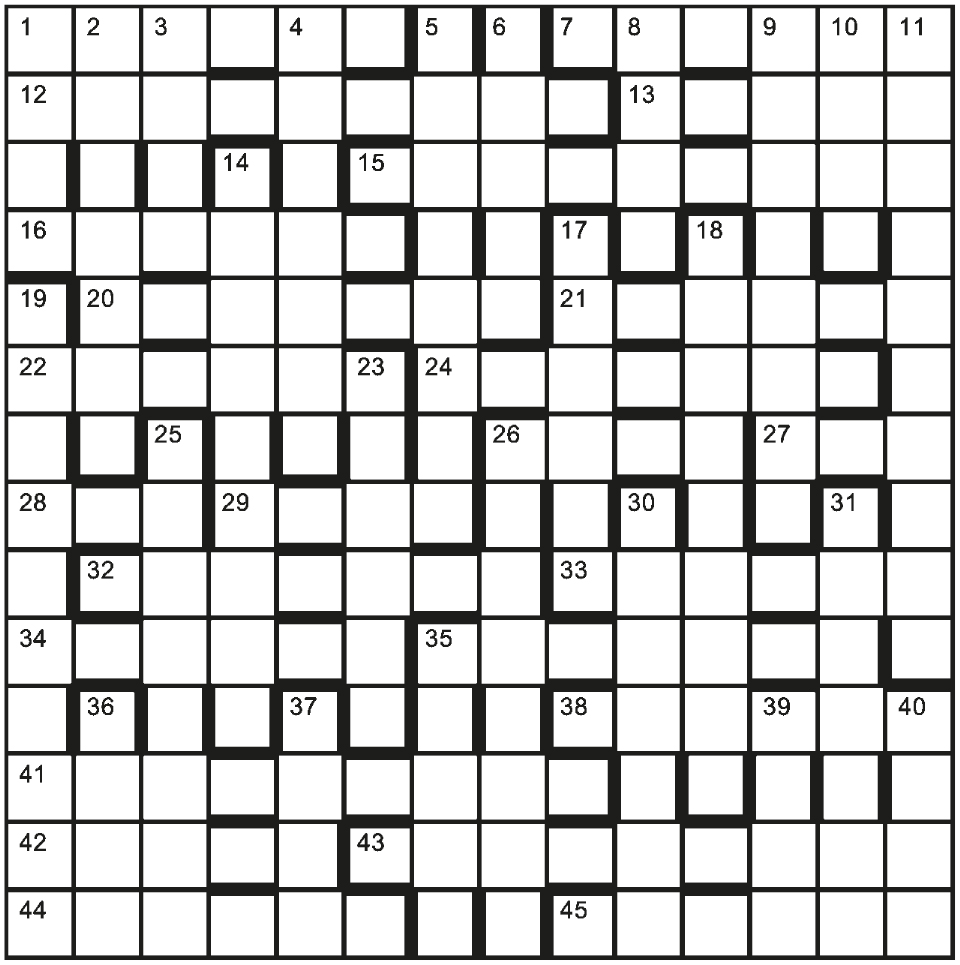

2698: Au pairs

Fourteen unclued lights comprise seven pairs.

Across

7 Looked for nothing when leader makes a U-turn? (6)

12 Medical instruments deal with something breaking old cast (9)

13 Maybe Queen’s speech is without purpose, on reflection (5)

15 Shot bird left, eaten by parasite (9)

16 Twins, perhaps extremely amoral, notable (6)

21 European dictionary contains chestnut for ‘imitated’ (6)

22 Wasted new mortgage in Scotland (6)

24 Coterie didn’t regularly boast duke (2-5)

27 Cut shaft, losing line (3)

28 Bird’s bone uncovered (3)

32 Think ancient Persian priests will stop in east (7)

33 Times introducing trendy revolutionary snack (6)

34 Port that iså red (6)

38 Press release before opening of enormous great structure (6)

41 More than one cocktail is a quid, surprisingly, around Ireland (9)

42 Exhaust unserviceable, emissions primarily amiss (3,2)

43 Hard test crushes son, at sea, way behind the rest (9)

Down

2 Just this splits bare metals (7)

3 Aussie idiot’s no good around legside (4)

4 Acetone almost corrupted sulphur compounds (7)

5 Foot, mine being bathed in English ceremony (8)

6 Pier having a black appearance? (5)

10 Catch broadcast of what golfer may have done (4)

14 Formerly not employed, aunties worried about it (9)

17 Chef’s beginning to chop up meatballs (6)

18 Those maintaining form in Oxford and Balmoral, say (9)

23 Bound to include papers put in order (6)

26 Youngsters lost fancy neckwear clips (8)

30 Where one may go awry in alert (7)

31 Alcoholic residue somehow vanishes when dehydrogenated (7)

35 Woolworths embraces value (5)

36 Mum starts to serve up salmon (4)

37 Old man holds aloft pre-adult peacock? (4)

39 Hawk emerging from lake covered in mist (4)

Download a printable version here.

A first prize of £30 and two runners-up prizes of £20 for the first correct solutions opened on 28 April. Please scan or photograph entries and email them (including the crossword number in the subject field) to crosswords@spectator.co.uk, or post to: Crossword 2698, The Spectator, 22 Old Queen Street, London SW1H 9HP. Please allow six weeks for prize delivery.

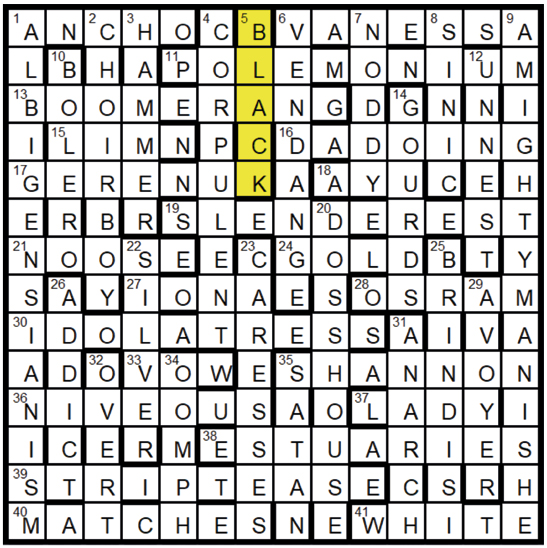

2695: Struck hard – solution

The theme-word is SMITH which can be preceded by GOLD (24A), LADY (37A), HAMMER (3D), BLACK (5D) and SILVER (22D). The pertinent quotation ‘A mighty man is he’ at 9D comes from The Village Blacksmith by Longfellow. BLACK had to be shaded.

First prize Andy Grady, Tutbury, Staffs

Runners-up Steve Reszetniak, Margate, Kent; Oenone Green, Feltham, Middlesex

Labour has once again betrayed grooming gang victims

Parliament’s last day before recess is usually a dull affair. A one-line whip allows MPs to return to their constituencies early and the matters for debate are deliberately parochial. When the Commons rose for Easter this week, the government could have expected attention to have been even more desultory than normal, since politicians and the media were focused on the fallout from Donald Trump’s global tariff war. Which is why it is all the more concerning that the Home Office chose that afternoon to slip out the announcement that it was retreating from its commitment to investigate the operations of grooming gangs in five local authorities. Someone must have thought it was a good day to bury bad news.

The government’s new approach to grooming gangs is an invitation to the guilty to evade their day in court

The commitment being watered down was already thin gruel. Rather than establish a national inquiry – as the opposition requested in January – into a scandal that ruined the lives of thousands of young women, the government opted for five discrete local investigations and pledged £5 million to support them. Seeing as the investigative work of GB News reporter Charlie Peters had established that grooming gangs operated in 50 towns and cities across the country, the selection of just five for scrutiny was inadequate. Given that a past inquiry into child sexual abuse in just one local authority, Telford, cost £8 million, the sums allocated for investigation were insultingly paltry.

Initially, though, there was the hope of some rigour being applied to the process. In January, a respected KC, Thomas Crowther, was appointed to draft the framework for the inquiries. This raised the prospect of an attempt to hold local authorities accountable for their failures.

Now even that hope has been extinguished. Crowther has been sidelined and ministers have decided they will oversee the scope of any investigations. Worse, they have given local authorities a veto over any rigorous examination of events.

Following ‘feedback’ from the councils involved – in other words, a concerted pushback against failures being uncovered – local authorities may now adopt a ‘flexible approach’ when it comes to using the money originally earmarked by the Home Office for independent inquiries. Councils can instead opt for ‘more bespoke’ work, such as hosting ‘local victims’ panels’ or undertaking ‘locally led audits of the handling of historical cases’.

The government’s new approach is an invitation to the guilty to evade their day in court. The abuse of young women in so many towns and cities occurred because individuals in local authorities were at best neglectful and at worst involved in criminality. The failure to insist upon properly independent scrutiny is deeply worrying. How can anyone, most of all the victims, have confidence that the institutions which have repeatedly failed will welcome the searching questions required?

The shadow minister responding to Labour’s retreat, Katie Lam, was admirably forthright in delineating just how much the process has betrayed the victims. The scale and nature of abuse; the targeting of vulnerable girls, often in care settings; the intertwined nature of criminal activity and clannish community cover-ups – all demand a much more thorough approach than the government is ready to offer.

Jess Phillips, the minister responsible for tackling violence against women and girls, has a strong record in supporting victims and campaigning for action against abusers. Her commitment to highlighting past failures, including by Labour local authorities, should be applauded. It is therefore all the more regrettable that her courage has failed her at this moment.

She may believe that some of those most anxious to see these crimes pursued have ignoble motives. That was also the initial reaction of the Times reporter, Andrew Norfolk, who first uncovered the scandal. He was concerned that by laying bare the ethnic and religious backgrounds of the overwhelming majority of abusers, he would give succour to the arguments of right-wing extremists. But he concluded that the truth, however uncomfortable, must be pursued when victims have been marginalised, ignored and forgotten. He also recognised that a failure to discuss difficult questions openly only helps such extremists even more.

It is of course true, as Phillips has argued, that child sexual abuse is a crime which extends far beyond the operation of grooming gangs. It is right that any response to abuse and exploitation takes account of all the ways in which victims can be targeted. That requires more focus, attention and investment to support vulnerable children in care and to encourage fostering, kinship care and adoption.

But in acknowledging these truths, ministers must not hide from others. The sheer number of gang victims, the way in which social services, police and others failed them, the communal cultures which shielded abusers and the attitudes that indulged them all need the determined and unsparing attention of an independent national inquiry. Ministers must think again.

Portrait of the week: Trump’s tariffs, a theme park for Bedford and a big bill for Big Macs

Home

In response to President Donald Trump’s global tariffs, Sir Keir Starmer, the Prime Minister, said: ‘This is not just a short-term tactical exercise. It is the beginning of a new era.’ He wrote in the Sunday Telegraph: ‘We stand ready to use industrial policy to help shelter British business from the storm.’ The FTSE100 fell by 4.9 per cent in a day, its biggest such fall since 27 March 2020. The government published a 417-page list of US products upon which Britain could impose retaliatory tariffs after 1 May. Figures from the Office for National Statistics showed that, although in 2023 the UK imported £57.9 billion of goods from the US (10 per cent of all goods imports) and exported £60.4 billion’s worth (15.3 per cent of all goods exports), it exported £126.3 billion of services (27 per cent of all service exports) to the US, compared with service imports of £57.4 billion (19.5 per cent of all service imports). The Coventry-based Jaguar Land Rover said it would ‘pause’ all shipments to the US. The government tinkered with net-zero rules for vehicle-makers, whose import tariffs to the US had been put at 25 per cent. It also approved the expansion of London Luton airport, including a new terminal, and the Prime Minister signed a £50 billion agreement for Universal to build a theme park on an old brickworks near Bedford.

Russell Brand was charged with rape, indecent assault and sexual assault, charges relating to four women between 1999 and 2005. Dan Norris MP was arrested on suspicion of rape, child sex offences, child abduction and misconduct in a public office; he was suspended from the Labour party. Dion Arnold, a Metropolitan police constable, was charged with sexual offences including rape, allegedly committed while off-duty. Livia Tossici-Bolt, 64, was given a two-year conditional discharge and ordered to pay £20,000 after being convicted of breaching an abortion clinic protection zone in Bournemouth by holding a sign saying: ‘Here to talk, if you want.’ Her case had caught the attention of J.D. Vance, the US Vice-President.

Two Labour MPs, Abtisam Mohamed and Yuan Yang, on a trip to visit the occupied West Bank, were denied entry to Israel. In the seven days to 7 April, 154 migrants arrived in England in small boats. Birmingham sank deeper under rubbish and rats during its dustmen’s strike. Nick Rockett won the Grand National at 33-1, ridden by the amateur Paddy Mullins, whose father Willie trained the first three past the post.

Abroad

China, against which President Trump had announced a rise in tariffs to 84 per cent, itself announced a 34 per cent tariff on US goods. So Mr Trump confronted China with an extra 50 per cent tariff, provoking the reply: ‘China will fight to the end.’ Asian stock exchanges experienced falls. Shares in Asian banks and car-makers were down. Elon Musk said that President Trump’s trade adviser, Peter Navarro, was ‘dumber than a sack of bricks’. Australian farmers claimed that a 10 per cent tariff on their $3 billion beef exports to America would make Big Macs there more expensive. Among Australian territories landed with a 10 per cent tariff were the uninhabited McDonald Islands, 1,000 miles north of the Antarctic.

Kryvyi Rih in Ukraine, President Volodymyr Zelensky’s home city, was twice attacked by Russian missiles, leaving at least 20 dead, including nine children. Ukraine reportedly struck the only plant in Russia that produces fibre-optic cables for drones. Two Chinese citizens were captured fighting for Russia in eastern Ukraine, Mr Zelensky said. During a visit by Benjamin Netanyahu, the Prime Minister of Israel, against whom an International Criminal Court arrest warrant has been issued, Hungary announced its withdrawal from the ICC. Israel’s army admitted mistakes in an account by its soldiers of the killing of 15 emergency workers in southern Gaza on 23 March. Israel bombed military targets in Syria.

Yoon Suk Yeol was deposed as President of South Korea by the Constitutional Court, which upheld his impeachment by parliament after his attempt to impose martial law. Wisconsin elected Susan Crawford, a Democrat-backed judge, to serve on the state’s Supreme Court, despite huge spending by Republican opponents. The earthquake in central Myanmar on 28 March was said to have killed more than 3,500 people, with hundreds more missing. Eggs laid by a Galapagos tortoise held by Philadelphia Zoo since 1932 hatched for the first time. CSH

Heaven is an oeuf en gelée

Petroc Trelawny has narrated this article for you to listen to.

The cherry blossom was at its finest as I made my last early morning trip through Regent’s Park to Broadcasting House to present Radio 3’s Breakfast. When hire-bikes arrived in London, the planners were thoughtful enough to install a docking station outside my flat. I have used the heavy cycles for my commute ever since. Over the past 14 years I have become accustomed to the regular faces on my route: the man in an elegant dressing gown, surveying the morning scene while waiting for his dog to pee; the jogger who for some reason processes backwards along the pavement (whatever the supposed health benefits of his technique, I’ve always wondered how he avoids colliding with one of the elderly lampposts, some of which date back to the reign of George IV). The dedicated speed-cyclists of the 545 Racing Club – named after the time their peloton departs – acted as a marker on my morning schedule: if they were already gathered outside Denys Lasdun’s gloriously stark Royal College of Physicians, I knew I was running late. Whether I was cycling under moonlight on an icy January morning, in June when the sun was already dazzling, in autumn when I would slip-slide on the leaf mulch, my voyage through one of London’s great public gardens never failed to set me up for the day. I hope my colleague Tom McKinney will find similar inspiration during the journey from his home in the Peak District to the BBC’s studios at Salford, from where Radio 3 will now launch the new day.

BBC Television’s first home was Alexandra Palace in north London. For five decades its once magnificent Victorian theatre was used as a storeroom for sets and props. It then lay empty for 35 years until an ambitious restoration project brought it back to life. I went there recently to record a special episode of Friday Night is Music Night for broadcast during the week of the VE Day 80th-anniversary celebrations next month. The BBC Concert Orchestra shared the stage with the Central Band of the Royal Air Force. The biggest cheer of the night went to a 99-year-old member of the audience – Joyce Terry, who spent the war as a singer in the pioneering all-female Ivy Benson Band. After the Germans surrendered, it was Field Marshal Montgomery himself who ordered the ensemble to go to Berlin to entertain British and Allied troops. I asked what sort of reception they got. ‘What do you think?’ Joyce laughed. ‘We were two dozen attractive young ladies. We were pretty well received.’ After the recording finished, musicians in immaculate RAF 9A concert dress queued up for selfies with this elegant woman, a living link to VE Day 1945.

In a long weekend in Paris, where the espaliered trees in the Tuileries are bursting into leaf, I caught a bloody, beautifully staged and excitingly sung reconstruction of Rameau’s lost stage work Samson at the Opéra Comique. I stayed with my friend Henrietta, who gave me a battered copy of A.J. Liebling’s excessive (probably downright dangerous) food and drink memoir Between Meals: An Appetite for Paris. His description of a decent oeuf en gelée sent me hungrily to Brasserie Lipp, where I found the perfect example: yolk runny, aspic well herbed and salted, thinly sliced tongue holding it all together. Why does this attractive dish of low-cost ingredients not feature more on British menus? As Liebling says, it ‘is within the competence of any respectable charcutier’.

‘Bach Before 7’ has become the way many Radio 3 listeners start their day. In the few times when I have mischievously suggested we might ‘rest’ the feature, our inbox has overflowed, with 99 per cent of respondents demanding its survival. Salford colleagues assure me that it is safe. Over the years we have thoroughly mined the rich stock of sacred cantatas Bach wrote for the Thomaskirche in Leipzig. The secular cantatas are also well worth listening to. Some are comic, such as the ‘Coffee Cantata’; others celebratory, written for court feasts at Weimar or Köthen, or royal birthdays among the prince-electoral family of Saxony. Producer Susan Kenyon found a brilliant one for my final morning programme: the Cantata No. 71, written for a new town council in Mühlhausen, where Bach worked when he was in his early twenties. It includes the chorus ‘Crown the new regime in every way, crown with blessing!’ It was the perfect sentiment as I handed Breakfast on to Tom. And how splendid that the great Johann Sebastian Bach found inspiration not just from his faith and his princely patrons, but also from a local government election in early 18th-century Germany.

Marriage, motherhood and money: Show Don’t Tell, by Curtis Sittenfeld, reviewed

Show Don’t Tell, a collection of 12 short stories by the American writer Curtis Sittenfeld, explores marriage, sex, money, racism, literature and friendship from the 1990s to the present. There is a fine line here between memoir and fiction, with many of the female protagonists being Midwestern, bookish Democrats – quite like Sittenfeld herself.

In the eponymous story, Ruthie, a writer, dismisses the notion that ‘women’s fiction’ is perceived as giving off ‘the vibe of ten-year-old girls at a slumber party’. She reflects on internalised misogyny: ‘It took a long time, but eventually I stopped seeing women as inherently ridiculous.’

This volume can indeed be described as ‘women’s fiction’, whose subjects include mammograms, motherhood, menopause, pubic hair and clitoral stimulation. Sittenfeld explores the dilemmas of middle-class life and the sweet and sour nature of female friendship; and she successfully captures feelings and places – nostalgia for awkward youth, ‘usually hungover and let down’; dating and attraction, viewed as a ‘murky collaboration’; and some real zingers, such as ‘Harvard is a hedge fund with students’.

One character says about couples therapy: ‘The only thing worse than being in my marriage would be paying someone $250 an hour to discuss being in my marriage.’ The married state is described as ‘edible, but stale, like a cracker left on a sideboard too long’. And there is sound cautioning against ‘building a life on status markers’. Parents may relate to ‘the isolation of modern life’; to being called ‘cringe’; and to teens, glued to phones, condescending on the subject of veganism.

While the stories are funny and smart, they have an aftertaste of vanilla and are not as savage as, say, Lucia Berlin’s ‘A Manual for Cleaning Women’ or Nora Ephron’s essay ‘I Feel Bad About My Neck’. One contrarian character proposes that ‘great literature has never been produced by a beautiful woman’, but this is left unexamined. Similarly, a sharp story, ‘White Women Lol’, explores the uncomfortable ambiguity of micro-aggressions and the peril of becoming an accidental racist. But, again, it doesn’t go far enough.

Political hot cakes are dropped and then left to cool. ‘Non-binary’, ‘white privilege’ and being ‘performatively virtuous’ are phrases tossed about, and it’s hard to know whether Sittenfeld is being satirical or hedging her bets. But when she’s not in doubt, you certainly feel it: ‘Nancy, who is 50, tends to be overtly sexist in a way most men in 2014 no longer are.’

These stories, which invite us into the interior lives of kind but complex people, feel like a quiet celebration of coupledom, love and ordinary lives. They are catnip for marrieds. Vanilla ice cream is delicious after all.

What did John Lennon, Jacques Cousteau, Simon Wiesenthal and Freddie Mercury have in common?

Robert Irwin – novelist, historian, reviewer and general all-round enthusiast and scholar of just about everything – died last year. It might seem odd that a man whose previous works included the definitive one-volume introduction to The Arabian Nights and a controversial critique in 2006 of Edward Said’s Orientalism – not to mention what is one of the great novels about Satanism, Satan Wants Me (1999) – should have spent his final years working on a book about stamp collecting.

But fear not. This is not some weird aberration in a career of weird aberrations; it is, in fact, another weird aberration. The Madman’s Guide to Stamp Collecting, Irwin announces in his first paragraph, ‘will be of little or no practical use or interest to stamp collectors’ – a declaration that serves as both a disclaimer and a challenge. If you’ve come here looking for advice on watermarks and perforations, walk away. The book does not deal with stamp collecting ‘practicalities’. Instead, the following topics are covered:

The Psychology and Psychopathology of Collecting; Seriality; Miniaturisation; Classification; Nostalgia; Anal Retentiveness; Specialisation; Fraudulence; Commemoration; Rarity; Completeness; Sexuality of Collecting; Secrecy and Subversion; Digressiveness; Boyhood; Dutchness; Boredom; Death.

So, not a manual for the aspiring philatelist but rather a philosophical disquisition on subjects of interest to Irwin, and indeed to anyone who’s ever experienced, say, boyhood, obsessions, boredom or desire. The stamps are merely the means by which the subject matter gets delivered.

Borrowing a phrase and an insight from the Polish writer Bruno Schulz, Irwin figures stamps as portals, tiny little paper ambassadors for ideas and for people and places that often no longer exist and for events long forgotten. So there are notes and remarks on, for example, Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne project, Dennis Wheatley’s occult thrillers, the poems of Osip Mandelstam, and – at great length – praise for the work of the late Ciaran Carson, the consummate snapper-up of unconsidered trifles, whose great book The Star Factory (1997) provides Irwin with a kind of model for his own practices and procedures. ‘For me,’ he writes, ‘just the discovery of the writings of the Belfast poet and fiction writer Ciaran Carson has made this project worthwhile.’

Items pile up like stamps in a dealer’s stockbook. On one page we might get a passing remark about Frederick William of Prussia, who ‘collected a regiment of giant soldiers’ and who also ‘acquired women in the hope of breeding giants’. On another, there’s a discussion of the work of Ayn Rand, prompted by her article ‘Why I Like Stamp Collecting’, published in the Minkus Stamp Journal, in which she argues that stamp collecting ‘has the essential elements of a career, but transposed to a clearly delimited, intensely private world’. Then, suddenly, we have T.E. Lawrence’s role in the evolution of Arab stamp design, some stuff about Ellery Queen, and a description of the peculiar character of Iranian stamps: ‘Commonly they depict scenes of carnage, successful terrorism, imperialist outrages which must be avenged and glorious but bloody military triumphs.’ In arranging his remarks and thoughts about writers, artists and books, often only loosely linked by stamps, by cataloguing them and preserving them, Irwin not only describes but demonstrates the collector’s process of creating order out of chaos.

Iranian stamps depict imperial outrages which must be avenged and glorious but bloody military triumphs

The psychological dimensions of collecting receive, of course, due consideration, with Freud, Walter Benjamin and D.W. Winnicott all making their expected appearances, though frankly who cares about Freud and his ideas on anal retentiveness when you can simply luxuriate in a constant stream of Irwin’s wonderful asides: ‘Elizabeth David was informally associated with the Warburg Institute and she collected cookery books dating from the 17th century onwards, many of which she left to the Warburg library’; ‘By the way, useful information about the necessary procedures for issuing postage stamps, passports and flags and choosing a national emblem is obtainable from How to Start Your Own Country by Erwin S. Strauss.’

This is not to suggest that the book is all whimsy and flimsy. On the contrary: there are lots of rather serious and useful insights. Irwin is particularly good on the function of stamps in fiction – though he suggests that only two novelists have ever known much about stamps, Wheatley and David Benedictus, both of whom, he admits, ‘did not produce better novels as a result’. ‘Though stamps mostly play quite minor roles in novels, it is sometimes useful to focus on things that are marginal to the story’, because they ‘may tell us more about the author than swathes of passionate and high-spoken dialogue’.

Towards the book’s conclusion, we’re offered a glimpse of Irwin himself, the ‘would-be part-time hippy anarchist’ drifting from Oxford to London in the 1970s, and his progress towards acquiring a ‘truly weird mindset’. He was a bit of a stamp collector himself, in his youth, ‘but is there really a type?’ he asks. ‘Can one smell a stamp collector?’ The long list of stamp collectors that follows – including Freddie Mercury, John Lennon, Edward Said, Jacques Cousteau and Simon Wiesenthal – suggests not. Or perhaps it suggests that the type is simply ‘human’ and probably ‘male’, and possibly a little bit unusual.

I’ll admit that I shed a tear at the end of this, Irwin’s final work, recognising not just a fellow collector – of ideas, ephemera, stuff – but a fellow man emptying his pockets, as it were, at the end of a long life.

Event

The Book Club Live: An evening with Max Hastings

‘I felt offended on behalf of my breasts’ – Jean Hannah Edelstein

Jean Hannah Edelstein is a British-American journalist and the author of a 2018 memoir entitled This Really Isn’t About You, which was about her dating life, the death of her father and her discovery that she had Lynch syndrome – which predisposes her to some cancers, as it had her dad. There is a sickening inevitability that her Breasts is at least partly about her being diagnosed with breast cancer. Yet, this is an uplifting volume, as well as a short, sharp shock.

The three sections of the book, ‘Sex’, ‘Food’ and ‘Cancer’, mean that readers will know what’s coming. But before the final section, Edelstein writes perceptively about adolescence, her first bra and being made to feel even by her schoolteachers that she and her female classmates ‘walked around in our flagrant, provocative teenage bodies day in and out. If men regarded them as invitations – well, had we tried hard enough to stop them?’ Later, she is honest about weaponising a great rack, not least when she meets men in bars: ‘“I’m Jean,” I’d say. “I believe you’ve already met my breasts.”’

She writes measuredly about the assaults she was subjected to by colleagues – one when she worked in a bar and another when she was employed by a tech company – and strangers, including the teenage boys who pelted her with eggs so incessantly that she feared she would crash the bike she was riding. And she is funny about the glamorous illustration drawn of her to accompany a dating column she wrote for a men’s magazine, lamenting: ‘I’m not hot enough to be myself.’ But a friend said: ‘It kind of looks like you had a baby with Gisele Bündchen.’

In the part entitled ‘Food’, she becomes pregnant and considers the fact that her breasts are about to have a different purpose – to feed her son – as ‘a freedom. Even a revenge’. For starters, she is no longer subject to catcalls during this period. Her baby was conceived by IVF and is delivered by C-section, and she comments that this makes her feel somewhat like ‘a passive participant in his creation’. She goes on: ‘I wanted to breastfeed because I wanted to do something by myself, unmediated and unmedicated. I wanted something to be natural.’ Her maternal grandmother had called breastfeeding ‘the life of a cow’. Edelstein notes: ‘I also wanted to breastfeed because I wanted to experience the full utility of my breasts. For so long it had seemed that their sole purpose was as objects of pleasure: sometimes mine, very often other people’s.’ She candidly recounts watching her husband spill half of the milk she painstakingly expressed – before leaving her baby to go to a doctor’s appointment – and being unable to speak to him for hours.

She has another child, a daughter, and at the end of breastfeeding her, she reflects: ‘My breasts belonged to me.’ It is poignant that these are the last words before the final section. Aged 41, Edelstein is diagnosed with breast cancer. She contemplates the mastectomy that her surgeon says is necessary, although her cancer is at a very early stage. She remembers a long-forgotten boyfriend who had early male-pattern baldness and had once remarked how little time he and his hair had spent together. ‘I didn’t grow any until I was two and I started losing it when I was 20,’ he said. ‘In the total span of my life, my relationship with hair will have been relatively brief.’ She experiments with thinking of her breasts in the same way and the detachment helps to some extent.

She also contemplates the reconstruction after surgery, and I felt enraged for her when she reports that some misguided people

tried to help me see the bright side, implying that this was the opportunity for me to have the breasts of my dreams. I felt offended on behalf of the breasts that I had. What I wanted to say was: ‘These are the breasts of my dreams. The ones attached to my body.’

Her interactions with different surgeons – including the one who told her ‘Of course, you can’t expect them to look as good as natural ones’ – are fascinating and important. Roughly one in seven women in the UK will develop breast cancer in their lifetime. How wonderful that we now have this sane, detailed and funny account of Edelstein’s experience from detection to reconstruction. The writer and breast cancer survivor Rosamund Dean has described it as ‘a tit punch of a book, in a good way’. At 100-odd pages, it also powerfully makes the case that sometimes, a short book is best.