-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

In defence of single-sex schools

When I first became a teacher, I bought into the notion that single-sex schools were an anachronism – a result of historical happenstance that no longer had a place in the 21st century. I imagined all-boys schools as a macho world of Spartan dormitories and testosterone-charged classrooms. I assumed the boys graduated with repressed memories of traumatic hazing rituals and an unhealthy amount of anxiety around girls.

Then, after two exhausting years teaching English at a mixed comprehensive, I moved to an all-boys independent school to see what it was like. I enjoyed it so much that when I moved from London to Oxford, I decided to teach at another (although my current one is co-ed at sixth form). My experiences convinced me that, far from being relics from a more chauvinistic age, all-boys schools are needed now more than ever.

We know that lack of distraction from the opposite sex can help drive academic success: four of the top five state schools listed in the Times’s ‘Parent Power Guide’ are single–sex grammars. With lack of distraction comes lack of self-consciousness. The precious enthusiasm, intellectual curiosity and ambition that younger students have are all too often sledgehammered by puberty and a sudden need to impress. At same-sex schools those qualities can be nurtured a little longer.

At all-boys schools, stereotypically ‘un-cool’ pursuits such as chess or the model railway society or linguistic competitions not only exist, but thrive. There are no designated ‘girl’ instruments or subjects or roles, because there are no girls. Attributes such as talent, passion and a sense of humour take on much more value as social currency.

Despite the benefits, these schools are a dying breed. The number of single-sex independent schools has roughly halved since the early 1990s. Scotland has just three single-sex mainstream private schools left. There is also particular pressure on boys’ schools to go co-ed. There are only a handful of all-boys boarding schools left in the country, while the list of schools going co-ed for day pupils grows ever longer: Westminster, Winchester, Eltham College, Abingdon.

There may be practical reasons for this change: in two-thirds of fee-paying households, both parents work, and families may want the simplicity of dropping off sons and daughters at the same school gates. As fees become increasingly expensive, schools may also need to broaden their admissions to fill places. Yet the dwindling number of state all-boys schools suggests something else about the zeitgeist. The accepted view seems to be that boys do better with the ‘civilising’ influence of girls, while all-girls schools ‘protect’ girls from the waywardness of adolescent boys. This assumption was exacerbated by the moral panic of Everyone’s Invited, a campaign launched in 2020 in which prestigious all-boys schools were accused of being hotbeds of sexism and ‘rape culture’. It’s harder to justify all-male environments in an age when people are obsessed with ‘toxic masculinity’: a deeply alienating term that wrongly devalues many other ‘male’ traits and behaviours that should be promoted, such asself-reliance, stoicism or competitiveness.

All-girls schools face their own challenges. I know one that struggles with containing the contagious effects of anxiety and eating disorders, dealing with levels of hysteria last seen in The Crucible. As anyone who has been the subject of a surreptitious side-eye knows, teenage girls are capable of all kinds of bullying. Yet the cliques, complexities and cruelties of all-girls schools are rarely labelled ‘toxic femininity’ in the same way.

Far from being relics from a more chauvinistic age, all-boys schools are needed now more than ever

‘Single-sex boys’ environments allow boys to be boys, to develop at their own pace, and to inhabit their space as boys,’ says Helen Pike, Master of Magdalen College School, Oxford. ‘These schools are not monasteries, and their pupils encounter girls socially and intellectually in a variety of ways.’ In other words, they ensure that the phrase ‘boys will be boys’ is something to be celebrated rather than condemned.

The exuberance and enthusiasm of a teenage boy is very different to that of a teenage girl, but society doesn’t tend to view it as joyous or desirable in the same way. At best, it’s seen as mildly disruptive; at worst, pathological.

We rarely praise, or even enjoy, the physical, jostling, playground energy boys bring. One of my favourite parts of the week last year was lunchtime duty on a shared sports ground. Come rain or shine, boys from all different year groups would spend every minute they could playing makeshift games of tennis, cricket, hockey, football, tag. It should be pandemonium, but there’s a strange order to this chaos of kickabouts: boys throwing back stray balls; boys tapping in and out; boys making up rules; boys bantering and bartering between breaks. This precious vitality isn’t just for the athletic and sporty; indoors, there are clubs and competitions that I suspect would never be so well-attended if there was the pressure to look cool in front of the opposite sex.

Teenage boys have always got an unfairly bad rap. In the 1990s and 2000s, the media demonised them as ‘yobs’ and ‘hoodies’; now they are in the press as incels, gang members or school shooters. When people think of private school boys, the stereotype of Etonians running Westminster comes to mind. Yet the vast majority I have taught are fun, clever, respectful, charitable, hardworking, cheeky and charismatic in equal measure. They are all these things, perhaps the more so because they have been allowed to inhabit their space as boys, in an environment that allows them to develop at their own pace. All-boys schools are not the problem behind the stereo-types: in fact, they may be the solution.

The artist reviving portrait painting at Marlborough College

The art school at Marlborough looks different. When I was a pupil here in the mid-2000s, conceptual art was cool. Back then, art meant spray-painting a canvas with neon graffiti or making a sculpture out of rubbish. The art school would have been covered in all sorts of zany efforts at abstraction. What there would not have been, however, was much portraiture. And certainly not the abundance of remarkable portraits that now fill the walls. Something has changed.

This newfound enthusiasm for portraiture among Marlborough’s pupils is, in large part, thanks to a 25-year-old portrait artist, Grace Payne-Kumar, the college’s artist in residence since September 2023. For many years, Marlborough has hosted resident artists, encouraging them to pursue their own work while also inspiring and teaching students.

I meet Grace in her studio, a beautiful well-lit space above the school’s Mount House, a Grade II-listed Georgian building that serves as a gallery where students, teachers and the wider community can view artwork by pupils and visiting artists. Grace’s studio is filled with portraits. Some are unfinished; all are compelling. I notice a few are turned upside down. ‘It helps me see them with fresh eyes when I come back to them,’ she explains. ‘If you stare at something for too long, you lose that perspective.’

Grace’s work builds on the rich tradition of European portraiture, a discipline she learnt at the Charles H. Cecil Studios in Florence, where she was trained in the ‘sight-size’ method. This technique, once employed by masters such as Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Lawrence and John Singer Sargent, involves placing the subject and the canvas side by side to achieve exceptional accuracy in proportion and likeness. It remains a cornerstone of classical art atelier training – a legacy that Grace is now passing on to Marlborough’s students.

‘Pupils here are encouraged to try every-thing,’ she says. ‘You can go to the observatory and see the stars. You can go trout fishing in the pond. You can come up here and try sight-size painting.’ Judging by the number of portraits lining the walls, it’s clear the method has captivated Marlborough’s pupils. For students pursuing art at A-level or GCSE, or even those intrigued by the techniques of classical portraiture, Grace provides expert guidance. ‘It’s like a mini-Charles Cecil,’ she says. ‘A taste of atelier training.’

‘Some come to the studio not only to paint but to decompress. Art is a huge stress reliever’

The results are striking. ‘The pupils are creating so much work, which is wonderful to see,’ Grace notes. ‘As a teacher, it’s rewarding to watch their progress. Some come to the studio not only to paint but to decompress. Art is a huge stress reliever. It’s also incredibly fulfilling to see students who wouldn’t usually have gravitated towards art slowly gain confidence as they explore different techniques.’

Grace runs weekly life-drawing classes and even introductory lessons for parents and children. Most days, she has a model in her studio (a portrait normally requires multiple sittings) and students are encouraged to work alongside her. ‘That’s how it’s done in ateliers,’ she says. She is also eager to share her expertise. ‘Last year, I worked with a student whose project was inspired by Titian. We explored his techniques, did some paint grinding, and discussed his methods in depth.’

She is keen to make portrait painting seem a viable career path. I suggest that it must be inspiring for pupils to see a successful portrait artist who is only a few years older than themselves. ‘I suppose it makes it feel more accessible,’ she says. ‘Like they could follow a similar route.’

When she isn’t teaching, Grace focuses on her own commissions – and demand is high. In 2019, she was a finalist for the Scottish Portrait Awards and won the Members’ Choice Award. A prestigious commission followed: the official portrait of Lady Dorrian, Scotland’s first female Lord Justice Clerk, which was unveiled in Parliament Hall in 2022. She was also commissioned to paint Jamini Sen, a pioneering surgeon and the first female Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow.

Her portraits now hang alongside those of Sir Henry Raeburn and Singer Sargent – a fact she takes pride in. ‘Sargent is my biggest influence,’ she says. ‘I introduce his work to students to explain the Italian concept of “sprezzatura” or “studied nonchalance”.’ I find this amusing, ‘studied nonchalance’ somewhat encapsulating the Marlburian attitude to life.

While Grace’s portrait style is rooted in tradition, her choice of subjects is refreshingly modern. Her heritage – British, Indian and Kiwi – shapes her artistic vision. ‘That mix is a huge part of who I choose to paint and represent,’ she says. During the school holidays, she has travelled to India and Mexico, expanding her knowledge of global portraiture styles.

English portraiture has historically been ‘commissioned by aristocracy’. ‘I enjoy using old master techniques to depict people from diverse backgrounds in terms of race and gender.’ She gestures to a portrait of the school’s Mandarin teacher, her pearl-embellished cardigan painted with Vermeer-like precision. Another work in progress is a portrait of Satish Kumar, the Indian-British activist and monk. There is nothing staid about Grace’s work; she has made classical portraiture feel youthful, modern and relevant. No wonder the pupils love it.

Grace’s tenure as artist in residence will conclude at the end of the school year, after which she plans to move to London to continue her career. Her presence will no doubt be missed. But if the walls of Marlborough’s art school are anything to go by, her influence will endure.

How should today’s pupils be disciplined?

On top of the canings and endless gym-shoe whackings – those ‘short, sharp shock’ corporal punishments endured by prep-school children (especially boys) until the late 1970s – what were the most memorable punishments inflicted on pupils born from the 1930s onwards?

To put today’s more humane prep-school punishments in perspective (they’re not even called punishments but ‘sanctions’), I asked people in their seventies and above which punishments they most remembered. ‘The Denzil Blip,’ said Julian Campbell, who was at The Hall School in London in the 1950s. ‘Denzil Packard had been a prisoner of war of the Japanese and had a mangled finger. Offending boys were clipped on the head, with this finger being the point of contact.’ There was also ‘the Rozzy Haircut’. This was given by Mr Rotherham, ‘who would take hold of your hair with his hand and pull your head down to grovel on the floor’.

Another described simple verbal terror. ‘The classics master had been in the Navy during the war. When presented with an incorrect translation, he would shout, “Balls, bollocks, bang my arse, frog’s bum and monkeydust”.’ Others mentioned ‘being made to learn the Benedictus by heart’, ‘running round the playing field’, and ‘detention every night, no Sunday exeat, and no sweets when the tuck shop opened’.

By the time I was at a girls’ boarding prep school in the 1970s, the punishment for frolicking after lights-out was to sit in silence facing a wall in semi-darkness for an hour, or to be made to make your bed again and again until it felt as if your arms would fall off. For boys, non-corporal punishments included writing 100 lines, such as ‘I must not fritter away my expensive education.’

The ultimate fear was that your parents would be told about your bad behaviour and there’d be hell to pay at home. Nowadays, parents all too often side with their child against the school. This is the kind of parental interference that makes being a teacher increasingly hard. As the sought-after private tutor and former prep-school master Ed Clarke said to me: ‘These days, invoking discipline in the classroom can create a rod for your own back, because the child tells their parents, the parents contact the deputy head, and you get called in for a bollocking.’ A more confident school stands up to parents.

The pervasive atmosphere of fear and shame recalled with a shudder by many seems to have vanished from today’s prep-schools. Punishments are now restorative more than punitive. The entire philosophy of the relationship between pupils and staff has changed. The theory that good behaviour is best learned through fear has been ditched. Now children are instilled with the mantra ‘be kind’ and ‘respect others’. And that goes for both pupils and staff.

‘Very, very few children are innately unpleasant, but they’re human beings and they will make misjudgments’

‘Very, very few children are innately unpleasant,’ said Matt Jenkinson, headmaster of New College School, ‘but they’re human beings and they will make misjudgments. They’re learning to live alongside people who might irritate them. What we try to do is to forestall errors of judgment, talking to them about kindness and co-existence.’

When pupils do fall short, what all three schools said to me is that there needs to be transparency in how misbehaviour is dealt with. At New College School, there’s a ‘graduated system of sanctions’: a white referral form, a green referral form, and then (the most drastic) an orange referral form, involving a talk with the headmaster. ‘The hope,’ says Jenkinson, ‘is that you never need to get to the point of exclusion, which is nuclear.’ Recently the school has introduced the new first stage, the white slip before the green slip, which denotes: ‘We’re not angry, but if this carries on, it would escalate.’

Hilary Phillips, head of the girls’ prep school Hanford, says: ‘It’s not so much we’re imposing discipline – we’re teaching the girls self-discipline. If a girl has misbehaved, I’ll make sure I find her when she’s with the guinea pigs or the ponies, or sitting in a tree with her book, and I’ll say, “Do you understand why that wasn’t a great course of action?”’

If the girls misbehave, ‘We’ll start with a gentle warning, then there’ll be a second warning, and then a punishment, starting with a conversation: “You’ve chosen to do this three times, which shows you don’t care. Your action is going to create a reaction.”’ Then follows an ‘SYR’ (‘Serves you right’): a tedious task tailored towards the misdemeanour, such as cleaning out the minibus, or wiping muddy cross-country trainers.

‘We welcome mistakes – we’re a prep school,’ says Kath Harvey, deputy head of pastoral and safeguarding at the Dragon Prep. ‘What we aim to instil in the children is intrinsic motivation: a moral compass which tells them “This is the right thing to do.”’ To deal with mistakes, the school has a tiered system to promote awareness of behaviour. ‘We start with a “there-and-then reflection” at the end of the lesson, escalating to a meeting with the head of year, and then to a meeting with the senior leadership, if needed. “Talk me through your decision-making,” the children are asked, requiring them to reflect upon what went wrong and how they’d do things differently next time.’

In the boarding houses for 200 full boarders and 100 flexi-boarders, there’s a relaxed, homely atmosphere. But ‘consistent poor decision-making will result in a loss of privileges, such as not being allowed to go into town, or loss of tuck, so children learn there are consequences for unconsidered actions’.

With these humane and non-humiliating methods, and pupils being treated as mature, thinking beings from a young age, the next generation is being prepared for adulthood. But they won’t be able to entertain their grandchildren with stories of the ‘Denzil Blip’ or the ‘Rozzy Haircut’.

Which school gate drop-off tribe are you in?

It wasn’t until I locked eyes with a Premiership rugby player as I got out of my car at 8 a.m. that I realised I might need to up my game for drop-offs at the children’s new school. I would need to start wearing eye make-up, for starters. I should also give a little more thought to an outfit than picking up yesterday’s T-shirt and cut-off jeans from the bedroom floor – although ‘outfit’ is one of those words that makes me wince, like ‘gift’ or a ‘pop’ of colour.

Still, ‘outfits’ are what a certain type of woman around here goes in for. Among a sort of country-prep-miles-from-anywhere subset, you will find mothers trying their best to fit into what the Times has identified as the ‘Ganni Mum’ tribe. Named for their devotion to the Scandi brand (lots of leopard print/shapeless candy-coloured gingham dresses/blouses with puffy shoulders/chunky Chelsea boots), in urban areas, Ganni Mums are married to Henrys (High Earners, Not Rich Yet) and have elbowed out the beige Yummy Mummies.

But out here in the furthest reaches of East Anglia, the school-gate mothers haven’t quite perfected the Ganni Mum look. Partly this is because the nearest branch of Ganni is a good three hours away and so they must rely on local boutiques (another wince word) selling knock-off styles, or Vinted. Other rural areas are less deprived: Wiltshire mothers can find Ganni clothes stocked on Marlborough high street.

The other reason these women haven’t nailed the look is because what really matters to rural school mothers is inherited wealth. When an urban Ganni Mum arrives in the countryside, with her obvious new money, it’s time to start looking for schools elsewhere. An influx of Henrys from London and their WWWs (Wives Who Work, I just made that up) is vulgar. It is certainly reason enough to pull Arthur and Willow out of the school and send them down the coast road to the Other Prep, the one that can boast pupils with actual titles. (Every family here has a son called Arthur; I swear I once met a woman with two Arthurs among her extensive brood, privately educated across five counties, but then I may have drunk too much Picpoul.)

Here in the country, obvious ‘professional’ clothing is a no-no for the school-gate mothers. It’s an indicator of having neither family money nor a self-made husband to pay the bills. But rural-school mothers still cling on to their white Veja trainers, a nod to the urban Yummy Mummy, whom they simultaneously revere and look down on.

At Oxford’s Dragon School, mothers are no longer eccentric dons’ wives but ‘wealth with an urban twist’

I long to hear David Attenborough’s commentary on school-gate mothers, but as written by Helen Serafinowicz, co-creator of Motherland and Amandaland. Really, The Good Schools Guide should start including a paragraph on each institution’s tribes, so prospective parents can decide if they’re your people or not.

St Hugh’s in Oxfordshire is ‘all Lululemon and Verbier baseball caps’, a friend discloses. ‘It’s very sporty – everyone’s going back to their tennis courts after drop-off for lessons with the coach they’re probably shagging.’ This surprises me as I’d have imagined it to be tweedier, but then Oxfordshire isn’t proper countryside. I don’t think these women walk their own dogs or have much need for country clothing.

In Oxford itself, mothers at the Dragon School are no longer eccentric dons’ wives but ‘wealth with an urban twist, so Chanel pumps’, advises another friend. And at Farleigh in Hampshire, ‘there’s a bit of stealth wealth but a lot of Schöffel gilets’, aka Cirencester life-jackets.

I don’t fit in with any tribe (unless you count muddy), so watch all this with bemused anthropological detachment. Back when I lived in south London it was much more simple: the mothers who’d managed to keep hardcore careers going (corporate law, fund management) wore dark suits under smart coats, while the freelancers’ uniform usually involved some grey cashmere and what fashion writers call ‘athleisure wear’. My leggings were always Sweaty Betty rather than Lululemon – I was on a budget. One mother at a London school reports on the rise of the ‘bumbag and bum-lift leggings’ look. It says: ‘I’m busy (hands free!) but I still find time to keep myself in shape.’

Nowadays, I like to sling a tailored waterproof coat over my freelance uniform and pop a knife in the pocket for cutting baler twine, so I can go out and hay the animals before the school run. For the mornings when I must hammer through the lanes to catch the London train, I swap the leggings for a pair of high-waisted tailored trousers. My beloved black velvet Isabel Marant boots, a relic of the Dean Street days, live in the car. They are pulled on at the station, to avoid them being coated in the mud that penetrates everything, even the inside of our organic eggs. At Liverpool Street, I reach into my pocket for my bank card and realise that the knife is still there and I am, in fact, ‘carrying’.

The lessons I learned as education secretary

Michael Gove has narrated this article for you to listen to.

Education secretary really is the best job in government, though sometimes it doesn’t feel that way. Lives can be transformed – hopefully for the better – as a direct consequence of the decisions you make. But you are also firmly in the firing line. There’s no other area of public policy in which everyone is an expert. Only a minority of us have fought in battle, studied the impact of nitrates on chalk streams or contemplated what the correct approach to sanitary and phyto-sanitary standards should be in a trade agreement. But we’ve all been to school. And we all have views – sometimes deeply entrenched and emotional – about what constitutes a good education and therefore sensible education policy.

So any education secretary who wants to change things can expect to run into controversy. Ken Baker was held up to execration by teachers’ unions and academics in university education departments for introducing what was considered an over-rigorous national curriculum, paper and pen tests which would leave too many students feeling like failures and an inspection regime which judged schools against each other. David Blunkett, Charles Clarke and Ruth Kelly in turn were criticised by the same unions and scorned by the same university departments for, respectively, insisting on higher standards of numeracy and literacy, bringing in ‘unqualified’ teachers to the classroom (through Teach First) and giving more schools greater autonomy through the academies programme.

During the four years I spent in the Department for Education I built on their work. Sure enough, I found myself being attacked by the same people for much the same reasons. But while I didn’t (most of the time) go out of my way to seek confrontation, I felt the whole point of being in office was to drive change. I wanted England’s children to have the very best education they could.

My own life was transformed by education. I spent the first four months of my life in care. But I was lucky to be adopted by loving parents. Both had left school at 16 and they wanted opportunities for their own children they had never been able to enjoy. Their hard work allowed them to invest time and money into my, and my sister’s, schooling. My mother worked at the school for the deaf in Aberdeen my sister attended and my father’s small business profits (small in every sense) were devoted to sending me to the city’s only fee-paying school for boys.

I was lucky. But I was conscious that if I had not had that parental love and support, a child like me who had been in the care system would have most likely faced a truncated or disrupted time in school, would have left with few or poor qualifications, and would have limited horizons in the future. My aim in government was to ensure that a child’s future did not depend on contingency or chance, on accidents of birth or the lottery of geography. Every school should be supported to strive for excellence.

In opposition I pointed out that, for all the gains we had seen in state education over preceding years, we were still falling behind nations that we should regard as comparators. And, worse, the gap in our schools between the educational achievement of richer and poorer children was growing. The ambition I set was to both raise the bar and narrow the gap. It was, I maintained, both economically inefficient not to make the most of every talent and socially unjust to allow the already privileged to benefit more from schooling than those with fewer advantages.

Making the case on both economic and ethical grounds seemed to me the right way to secure funding for schools at a time when austerity was looming elsewhere and the best way to convince others that failure to reform was a moral failure.

My aim in government was to ensure a child’s future did not depend on contingency or chance

I was helped enormously by my colleague Nick Gibb, that rare thing in politics: a man without ego, only principles. He had developed a policy programme which would improve reading in primary schools through the effective implementation of systematic synthetic phonics, a programme to improve numeracy by ensuring every student could achieve maths mastery, a programme to improve discipline by giving head teachers new powers over behaviour and a programme to end grade inflation by making exams and league tables more honest. He had based his approach on close study of effective classroom practice from around the world and underpinned it with an understanding of the science of knowledge acquisition culled from wide reading of authors such as Daniel Willingham and E.D Hirsch. He was both Sam and Gandalf to my faltering Frodo.

The economic case we made helped convince George Osborne in the Treasury to ringfence school funding. The ethical case we made convinced David Cameron to throw enormous political capital behind the revenue George gave us. And the detailed work Nick had undertaken gave us a programme ready for implementation straight after the coalition government was formed.

We were also lucky in that the Liberal Democrats, at that time, had developed ideas on education strikingly similar to our own. That was down to the party’s education spokesman at the time – David Laws, the single brightest and nicest Liberal in history, not excepting William Gladstone, Richard Haldane or Herbert Asquith. When we went into coalition with the Lib Dems we faced, at least initially, not a messy compromise but a happy consensus.

If we had the money, the plan and the allies, why did we run into problems? Well, that’s down to one big thing and many small ones. The big thing is that arguing that any system or organisation needs to change will be interpreted by many within that system or organisation as an attack on them. I argued that there was much to be proud of in our school system and in every speech praised brilliant state schools, lauded great heads and maintained (which was true) that we had the best generation of teachers ever in our schools. But in the ears of many, that praise was drowned out by the case we were making for urgent change. The generous words were a string serenade lost in the drum roll and trumpet cry for reform.

Could that have been avoided? Could I have done better at ‘carrying the profession with me’? Can a public service ever be reformed without those within it hearing the case for change as, at the very least, an implicit rebuke to them for their acquiescence in under-performance?

It might be possible. But I haven’t seen it done. As ministers of every party have found, and are finding, challenging incumbents in any field, even in the gentlest fashion, inspires resistance. Indeed, without that challenge, without showing you are resolute for reform, you won’t find allies within the quiet majority of professionals who know things can be better and who want the apologists for under-performance to be held to account. By demonstrating that we would not back down, voices within education were raised in our support and new voices were attracted to our cause. The heads of multi-academy trusts who were empowered to transform under-performing schools, the principals of new free schools liberated to aim higher, those teachers who believed in greater rigour and ambition, they became more numerous and more vocal precisely because the rising chorus of opposition to what we were doing in government convinced them that we were serious about change.

Challenging incumbents in

any field, even in the gentlest fashion, inspires resistance

And the small things that caused problems? Everything from my maladroitness in cancelling funding projects my predecessor had invested in (such as the gift of free books through the charity BookTrust) to the knock-on effect of requiring a 19th-century novel to be taught in GCSE English literature (some schools abandoned the texts they’d been teaching already instead of augmenting the curriculum with just one more book – so stories developed about me ‘banning’ Of Mice and Men and To Kill a Mockingbird when some teachers had chosen to ditch them rather than do a little more work).

The allegation that I had indeed banned these enlightening texts even led to a crowd of Socialist Workers party activists invading the Department for Education one morning and occupying the entrance hall in protest. It was, remarked my aide, the first time a Tory minister had been denounced by Trotskyites for being too anti-American. Such are the curious workings of the woke mind that Of Mice and Men was subsequently erased formally from the GCSE curriculum in Wales because it was deemed ‘racist’ and ‘psychologically and emotionally’ harmful for some black children. Wales’s children’s commissioner, Rocio Cifuentes, wanted to spare the principality’s 16-year-olds unnecessary trauma. As I said, education policy is the one area everyone has an opinion on – and is therefore treacherous ground for any politician.

Together that big problem – resistance to change among many incumbents – and the little problems – the clumsy execution of some policies – were weaponised by those same teaching unions and their friends in academia who disliked being held to account for not doing better for our children. I now look back on that time with a greater degree of equanimity because I feel the changes we made were vindicated by the progress our children have made in every international measure of school performance. But I am left with one lesson I would pass on to anyone who gets the chance to do what is a wonderful job: if you find the unions are praising you and the academics in university education departments proclaim themselves your allies – ask yourself, as Mrs Gaitskell did of Hugh: ‘Are the wrong people clapping?’

How to educate your child privately – without paying VAT

For some parents, VAT on school fees is the straw that’s broken the camel’s back. The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates that between 20,000 and 40,000 pupils will be withdrawn from the independent sector. An answer to a parliamentary question revealed that 46 private schools closed between January and October last year. It is safe to assume more will follow.

But if you really want to, there are still a couple of ways that you can educate your children privately without having to pay VAT. What about sending them to school abroad? What has proved devastating for some private schools in Britain has proved good business for Chavagnes International College, which is like an English country-house school complete with quadrangle and chapel but set in the Vendée countryside, 30 minutes’ drive from Nantes.

‘We’ve had enquiries from six or seven families interested for September, who say VAT on school fees in Britain is a factor,’ says headmaster Ferdi McDermott. The Catholic institution can trace its history to 1802 but was refounded as a boys’ school in 2002. At present, only five of the 40 pupils in the school have parents resident in Britain, with others coming from the US, Spain and Ukraine, as well as France. The practicalities of educating your children in the French countryside are surprisingly easy: the school ‘bus’ is Ryanair flight number 8503 from Stansted to Nantes, which takes 90 minutes and can cost less than £20.

Chavagnes’ fees, too, are enticing for UK parents. Including boarding fees, they range from €18,950 (£15,900) a year to €25,950 (£21,800) a year for sixth-form pupils. And you don’t need to worry about the prospect of VAT being added to private school fees in France. ‘The government hasn’t thought of taxing private school fees,’ believes McDermott. ‘Most private schools here are run on a shoestring by religious orders. The debate revolves more around whether the state should be helping to fund them.’ There are plenty of such schools to choose from. The International Schools Database lists 41 English or bilingual secondary schools in France, 20 of which are in Paris and six in and around Nice. If you want to send your kids to school by Eurostar there is an international school in Lille and a further 20 secondary schools in Brussels which teach in English. Thanks partly to Britain’s days in the EU, Belgium has rich pickings for English-language schools, with another four in Antwerp and one in Ghent. As for the Netherlands, there are 13 English-speaking international schools in and around Amsterdam.

Chavagnes International College is like an English country-house school but set in the Vendée countryside

If you want a full country-house boarding school education without the VAT, there is nowhere better than Ireland. St Columba’s, outside Dublin, offers cricket, chapel and the lot for between €24,132 (£20,300) and €28,966 (£24,300) a year for full boarding.

If you don’t want to leave Britain, there is still one way you can give your children a private education while depriving the taxman. Private tuition remains VAT-exempt so long as the tutor is a sole proprietor or in partnerships and the subject is one which is widely taught in schools or universities. According to Tutorful, which matches parents with private tutors, the average cost of private tutoring is £37.45 per hour. Assuming 25 hours’ tutoring a week for 30 weeks a year, you can turn your home into a private school – with one-to-one tuition, to boot – for around £28,000 a year. If you can match up with other parents and have your children taught in groups of two or three, you might be able to create what is effectively a mini private school for half this or less, assuming you can fly under the radar of regulators and convince them that you are simply educating your child at home rather than in an illicit, unregulated school. By contrast, the average fees for boarding schools are £42,460 a year and for day schools £18,063 a year, according to the Independent Schools Council.

While tutoring is primarily used for supplementing rather than replacing schooling, there are surprising numbers of parents who choose to educate their children entirely by private tutor – following the example of the royal family before the then Prince Charles was sent kicking and squealing to Gordonstoun. According to Tania Khojasteh, education director of Über Tutors, 5 per cent of the company’s clients don’t send their children to school at all. ‘It is an increasing trend,’ she says. ‘They are all British parents.’ It is a route that is especially favoured by parents of special needs pupils, or children who have struggled to fit in at school. Since Covid ended face-to-face schooling for months on end, the possibilities for home education have become clearer. According to a government census, there were 111,700 pupils educated at home on a single day in autumn 2024, with councils receiving 66,000 new notifications in 2023-24 that parents were educating children at home. The census did not investigate how many of these cases involve parents teaching their own children and how many were using tutors for part or all of the time.

Using home tutoring exclusively does mean your child will miss out on the social aspects of school but it prompts the question: if the government is happy for private tuition, along with higher education tuition fees, to remain VAT-exempt, what is the justification for charging VAT on private school fees? The exemption for tutoring seems to indicate that the government believes education is a social good which should not be taxed, but that if it is in some kind of organised, institutional setting then it deserves to be clobbered. This is not entirely logical – and makes the VAT raid look all too much like class warfare.

The enduring power of school dinners

Cornflake tart. Spam fritters. Green custard. Turkey twizzlers. Chocolate concrete. These are some of the dishes that instantly transport you to the school lunch hall – and inspire either pure nostalgia or horror.

Over the past five years co-hosting Table Talk, The Spectator’s food and drink podcast, I have spoken to people from all walks of life – politicians, chefs, writers, campaigners, entrepreneurs and artists – and they all have unique relationships with food.

But school food defies all reason. It presents a binary, true love or hate. Some look back with delight, seeking out spotted dicks and instant mash for ever more, though none tastes as good as the dishes they had at school in Kettering in 1989. Others can barely look at a rice pudding without gagging.

There’s something powerful about school dinners: they stay with us. And often they play a role in defining how we think of the institution we attended, and of food itself.

Many a book captures this power. The endlessly replenishing wish-fulfilment feasts that fill the dining hall of Hogwarts, the ritualistic taking of kaffee und kuchen at Elinor M. Brent-Dyer’s chalet school series, and the punishingly bad and scant porridge ‘which looked like diluted pincushions without the covers’ at Dickens’s Dotheboys Hall. Such descriptions tell us far more about the experience of being at the schools than pages of prose could.

But love them or loathe them, there’s a certain pride in those unusual dishes we had to endure. Like weird house names and the humiliation of cross country in public places, the food we survived at school forms an unbreakable bond. And the weirder the school dishes were, the more iconic.

Lara, who attended Westbourne House in the 1990s, tells me of a school-invented pudding called ‘Swedish Apricot’, a slab pie with an apricot compote base, a layer of whipped cream, and a cornflake and golden syrup top. A regular feature on the menu, it was a firm favourite. ‘It seemed so sophisticated,’ she recalls wistfully. Swedish Apricot has survived, still a staple of the current Westbourne experience; more than 25 years later, a recipe for the pudding appeared in the school magazine.

Lara’s was not the only school to make the most of cornflakes. Dora, who was at St Mary’s School Ascot, recounts a birthday treat that parents could pay for (how formal!): a traybake made up with the odds and sods from the breakfast buffet, a fondly remembered cereal hotchpotch.

It would be hard to get away with many of those esoteric school delicacies today. Manchester’s Labour mayor, Andy Burnham, who grew up in Newton-le-Willows in Merseyside, told me about a particularly popular lunchtime choice at his school, known among pupils as an ‘icy dinner’. An ice-cream van was allowed on to school premises in the middle of the day, and the icy dinner connoisseur would enjoy an oyster ice cream, a 99, and another ice cream boasting fan wafers.

Kirsty, who attended Knowles Hill School in Newton Abbot in Devon, mistily recalls her school serving deep-fried jam sandwiches, made with ‘cheap white bread, battered and covered in sugar, like extremely wrong doughnuts. They were amazing’. Of course they were, how could anything possibly compete?

Naturally, the older the school, the greater the possibility for traditions, and Hugo’s memories of school food at Eton in the early 2000s are deliciously in keeping with the school’s reputation. He remembers the 1940s-style pots of fish and meat paste that were always served with toast at chambers (the school’s mid-morning break) despite being entirely untouched. In the final year, certain students were invited to take part in ‘a champagne breakfast’ – a full English served with champagne – which took place at the normal boarding-school breakfast time of 7.30 a.m. and was followed up with a full day of lessons, which perhaps took the shine off it a little.

I am disappointed to find few tales of Eton mess being served at every meal, boys bathing in whipped cream and strawberries, lobbing broken meringues across classrooms. Most Old Etonians I speak to have no recollection whatsoever of it during their time there. Max does remember it being a mainstay from his school days, where presumably in a bid not to be ostentatiously self-referential, it was known as ‘strawberry mess’. He recalls the pudding making a regular appearance at the annual 4 June picnic (which, incidentally, does not take place on 4 June). But rather than being served by the school, Max remembers Eton mess as a dish brought from home by parents attending the picnic. This, he tells me, accounts for the deconstructed nature of the eponymous pud – ‘avoiding the absolute faff of making and transporting a pavlova intact down the M4’.

Certain Eton students were invited to ‘a champagne breakfast’, a full English served with champagne

Of course, boarding schools present many more opportunities for the oddities of adolescent eating. Hugo remembers, more keenly than the fish paste or champagne breakfasts, the Dolmio sauces and ‘extraordinary’ amount of spaghetti and Pot Noodles that dominated his boarding school days. ‘I once had four packets in a day,’ he says. ‘That really stayed with me.’ It’s hard not to be reminded of the transactional weight that such instant noodles and packet soups hold in prisons.

Such is the power of food – especially where the consumers have very little power elsewhere – that even seemingly everyday foodstuffs can take on disproportionate weight. When I speak to an Old Radleian, he speaks rhapsodically of an unassuming-sounding chicken sandwich, which I mentally dismiss as generic school canteen fodder. But lo, it turns out the boys of Radley feel differently: I stumbled upon ‘The history of Radley in 100 objects’, an online archive of things that sum up life at Radley College, and no. 11 is a – sorry, the – chicken roll. Described as ‘one of the great mysteries of Radley’, it shows the importance that everyday foodstuffs held to a bunch of kids who were at the mercy of grown-ups and time-tables, tracing its ‘iconic’ status back to written records from at least 1999.

Some schools are alive to the power of the food that they serve, and occasionally use it to make wider points to their pupils. Angus, who attended Westminster Under School, recalls an annual event where pupils would draw ballots to determine how they would eat for the day. ‘Rich man, poor man’ meant that one in ten of the students would eat like a rich man (‘a chicken pie, perhaps’), while the other nine were on short rations.

Though this was presumably meant to instil a sense of moral responsibility and a taste of injustice in the students, it didn’t always have the impact it should: to schoolboys, the bread and butter afforded to the poor men was more delectable than the fancier fare. Once the meal was over, the rich men were mercilessly chased by the poor, in Les Misérables style. Angus suspects the scheme no longer operates.

Things are different today. A combination of big contract companies that manage the dining of a whole bunch of schools, and the most bougie establishments boasting private chefs and nutritionists among their staff to cater to the demands of pupils and parents, mean that the days of idiosyncratic dishes that become the stuff of legend are over. Homogeneity reigns. Will this generation grow up with equally fond memories of authentically made tagine or gut-health-balanced acai bowls? Can Swedish Apricot survive? We can only hope so.

What’s the most insulting thing a teacher said to you? A Spectator poll

Matthew Parris

From the late Alan Lomberg, my English teacher at my school in Swaziland, in my school report: ‘I’m sure I have only slightly less high an opinion of Matthew’s literary abilities than he has himself.’

Sebastian Shakespeare

The late Alan Clark once described me in his diaries as a ‘tricky little prick’, but he was beaten to the punch decades before by a teacher who dubbed me a ‘giant prick’. To this day I’m not sure which is the greater compliment or insult.

Quentin Letts

The word that appeared in my school reports time and again was ‘facetious’. Facetious is a fine word, not least because it presents all five vowels in alphabetical order, but would a teacher nowadays dare use it of a pupil? I was an annoying child. A junior matron took one glance at me and slapped me, saying: ‘It’s little Letts, always smirking.’ I hadn’t done anything wrong, but she whacked me and I banged into the medicine cupboard door, cutting my eye. Still have the scar. But I didn’t really mind.

Craig Brown

The most memorable insult I ever received – memorable in the sense that it still haunts me – came from a sympathetic teacher at my prep school called Mr Buxton. Towards the end of a school debate about something or other, I plucked up the courage to stand and make a point. Heaven knows what I said. All I remember nearly 60 years on are his words to everyone else: ‘Give the poor chap a chance.’

Jonathan Miller

My life changed as a fifth-former at Bedales after getting back what I’d thought to have been an especially perspicacious and entertaining history essay. ‘THIS IS JOURNALESE!!!’ scrawled my teacher, Ruth Whiting, in her signature green ink. She certainly meant it to be an insult. I took it as career advice and have never looked back.

Roger Lewis

At my South Wales comprehensive, insults and personal remarks from the teachers flew thick and fast. It was meant to be character-forming. Fatty, Twiggy, Sticko, Pizza Face, Gravel Guts, Scabby Legs, Speccy Four-Eyes and Twp, a Welsh word meaning dim – perhaps derived from une taupe, French for mole. Owing to John Hurt as Quentin Crisp in The Naked Civil Servant, the effeminate (anyone who didn’t worship rugby) were called the Quentins. ‘You are worse than a Quentin,’ I was told. ‘You are quaint!’ Why is it always the games masters who perfected this sort of bullying? Decades later, I am so pleased if news reaches me of their death by cancer.

Matt Ridley

On arriving at Eton in 1970, I was sent to be tried out for the choir. A teacher played a chord on the piano and asked me to ‘sing the middle note’. Being tone deaf, I had no idea what to do. I tried ‘la’. He accused me of deliberately trying to avoid joining the choir.

Stephen Fry

‘An intellectual grasshopper’ is one that I remember from my German master. I don’t know whether I earned the epithet or what it even means, to be honest. Another was: ‘If he were truly as clever as he thinks he is, he would be the teacher and I would have the pleasure of ignoring him as he ignores me.’ Ouch.

Griff Rhys Jones

‘If brains were dynamite, you wouldn’t have enough to part your hair.’ My masters didn’t generally insult us, they just whacked us. We learned basic grammar – subject and object – by Dickensian process. ‘The master hits the boy,’ intoned our first-form Latin teacher, directing a stubby finger at his own red face and clumping each infant he passed. We loved it. We were ‘poodle fakers’. ‘Lazy tykes’. ‘Doomed’. Our backcombed barnets were ‘lank tresses’. Our zip-up Chelsea bootees ‘grossly illegal footwear’. We were ‘slackers’. ‘Dreamers’. ‘Dim’. Nothing was accidental. ‘Sorry your concussion has ruled you out of rugby. Are you still concussed or just naturally ignorant?’ Real abuse was reserved for reports. My headmaster specialised in withering scorn. ‘He thinks his charm is enough. I doubt it.’ ‘What happened to that charm then?’ a friend asked recently.

Bruce Anderson

I had just arrived at Campbell College and was labouring through my first gym period. The master in charge watched my efforts with a sardonic appraisal: ‘Did your previous school have a gymnasium?’ But the greatest insult I heard from a teacher had nothing to do with me. These days, it might have led to trouble. At a prep-school cricket match, one small boy could not land a delivery on the wicket. At the change of overs, the master from the other school addressed the incompetent: ‘What’s your name, boy? ‘Badcock, sir.’ ‘Your balls are worse.’

Catriona Olding

Kraftwerk-loving Stuart Mulholland started it. He called me ‘Swan Vestas’ because I was tall, thin and had red hair. In those days you could buy a cigarette and a match for 2p from the van parked outside the school gates. One morning my English homework jotter came flapping across the classroom and hit me on the head. Inside were the words: ‘Swan Vestas, you can do better. Take a leaf out of Boxer’s book and tell yourself, “I must work harder.”’

Richard Madeley

The worst insult a teacher ever threw at me was also the bitchiest. I was best friends with a boy this man clearly had a massive crush on. It was a classroom joke. One day my friend was injured on the rugby field. I was helping him off when the teacher ran over.

‘Why is Madeley helping you?’

‘He’s my best mate, sir.’

‘Madeley? Your best friend? You can do much better than him. I’ll help you. Madeley, go pick up the orange peels.’ Nice guy.

James Delingpole

My teachers never had to invent any insults for me because my surname did the job for them. If you yell ‘Delingpole’ in the right tone of voice – angry, appalled, disbelieving, or whatever you feel the particular moment requires – at a small, impertinent boy, it squishes him more than adequately.

Rory Sutherland

I regret to say I’ve chosen an easy target: it was always games masters who were the most horrible. There is a strangely Darwinian streak to games masters. If a pupil is not academically or artistically gifted, most teachers will at least persevere and do their best. But sports teachers are genetic determinists to a man: from the first millisecond they discern you have no athletic or sporting talent, they would treat you as a complete blot on the landscape and were happy to abuse you for the merriment of everyone else. In the 1980s, ‘poof’ and (for some reason) ‘ponce-eared poof’ were standard terms to describe anyone who disliked organised games. So when one particularly nasty games master’s son was flashed by a paedophile, most of us nerdy types saw it as karma in action, the natural justice of the universe reasserting itself.

Martin Vander Weyer

I have no recollection of being insulted by any of my schoolteachers. But at Worcester College, Oxford, at my last appearance before tutors and the Provost for a verbal final report after three fun-packed and occasionally riotous years, my economics tutor described me as ‘the sort of undergraduate who was supposed to have been abolished by the 1944 Education Act’. To which the Provost, the great and good Lord (Oliver) Franks, endeared himself to me for ever by responding: ‘Not at all, Martin is a valuable member of our community who has clearly enjoyed his time here, and we wish him well.’

Rachel Johnson

When I was at the European School in Brussels, all the English children were in the same class at the beginning, in the early 1970s. I was taught aged seven with my older brother, whom our teacher, Mr Black, considered gifted – but me not so much. For homework one day we were told to write ‘an exciting story’. I did my best but when my English book came back, Mr Black had written, ‘Oh how very boring Rachel’ at the end in thick red felt-tip pen. I still try to bear that in mind whenever I write a sentence.

Harry Mount

Bob Bairamian (1935-2018) taught classics at my prep school, North Bridge House, by Regent’s Park. His insults were jokes really. To punish me for getting a Greek verb wrong, he cried: ‘Put drawing pins on the juniors’ chairs!’ When he smashed his head in a car crash, he devised a new punishment: ‘Mons Minor [my nickname], come to the front and pick the scabs off my forehead.’ I adored him.

Melissa Kite

My maths teachers were baffled by me, and struggled to express how hard it was to teach me anything. I had one who used to call me Esmeralda, which everyone found very amusing. Another one used to bang his big ruler against the blackboard at some algebra or geometry he couldn’t get me to solve and scream: ‘Are you stupid? Why can’t you see?’ I wish I could have answered: ‘Because I can’t do maths and I never will be able to so I’d give up if I were you…’

Philip Hensher

I still admire my English teacher who boldly gave the class The Waste Land. At 16, I was a mad Wagnerian. We got to the lines Eliot quotes from Tristan. I thought it would be iconoclastic to remark: ‘Of course, Isolde dies in the end of an orgasm.’ Mr Buckley’s timing was concise and impeccable. ‘Inconvenient,’ he said with a flick of a glance. As a put-down of weary experience, as if he had heard every conceivable teenage attempt to shock, it had the quality of making me feel he’d got my number.

Sean Thomas

My cruellest nickname came from a history teacher I liked, who innocently noted that my surname came from the Welsh/Cornish: ‘As’ = son, of Tom. Gleefully my schoolmates seized on this, and I very nearly became ‘Ass’ – and ‘Asshole’ – for ever, a fate I avoided by urgently thinking up nastier, more diverting names for everyone else. Thus are writers born.

Petronella Wyatt

My maths teacher and I were standing in a classroom at St Paul’s Girls’ School, which I attended back in the 1980s. I had just failed my maths O-level. ‘Petronella,’ he said, ‘you cannot get through life on charm alone.’ As I began to purr, he added: ‘Incidentally, that was an insult.’

Julie Burchill

One of them told me that I would probably ‘end up’ as the editor of Private Eye. I was only 15 and I didn’t even know what Private Eye was. I still don’t know if it was praise or a diss.

When did RE teaching become so muddled?

I recently offered my services as a part-time RE teacher to my local comp, an inner-city affair with a Muslim majority. Yes please, said the nice headmistress: the Covid-blunted Year 11s needed all the help they could get with GCSE revision. The syllabus consisted of Christianity and Islam. What could go wrong?

The first thing that went wrong was that I talked about the Jewish roots of Christianity and Islam: Judaism was the original monotheism. ‘I don’t know if that’s right,’ said one girl, frowning. Well, you do now, I wanted to say. But of course what she meant was: I don’t know if you are to be trusted on this.

I consulted the textbook, for objective evidence. This is a book published by Pearson with the unlovely title: Revise Edexcel GCSE (9-1) Religious Studies B Christianity and Islam Revision Guide. I know: it sounds like it’s a supplementary revision guide. But it’s the only textbook that covers the course, so most cash-strapped schools tend to avoid buying supplementary books and use just this.

Oddly, there was no introductory section on the common parentage of both faiths. When we did move on to Islam, I was expecting the students to become more vocal, but the opposite happened. One question was on the Quran: how do Muslims treat it as a special book? Sullen silence. I suggested that the students draw on their experience. Does anyone have one at home? After some prodding, one boy said that it is kept in a special place, that nothing can be placed on top of it, and that if it is dropped it must be kissed twice. Someone else said their copy was used for family prayers, especially during Ramadan.

The next question on the worksheet was on Muhammad: list three things he did in his life. Someone volunteered that Muhammad taught people how to live a good life. Another boy remembered that he had been a shepherd before he was a prophet. Then: silence. This seeming ignorance was odd: these were pious youths.

So we consulted the textbook – obviously there would be a few pages on the Prophet. Er, no. Just a paragraph, in the section on prophets, and few scattered mentions elsewhere. There are 67 sub-sections in the Islam half, on things like ‘Wealth and poverty’ and ‘Issues in the natural world’. But nothing about the origin of this religion and the life of its founder. This also felt odd.

Of course any RE textbook is going to avoid controversy, but this one does so in a way that is almost comical

‘What else did Muhammad do?’ I asked. ‘He spread the faith,’ someone said. ‘Right,’ I said. ‘How did he do that?’ ‘Didn’t he fight some wars?’ Ah. Now I believed that the boy might have been correct about this, but I was anxious to have the support of the textbook before venturing into these deep waters. Maybe the information was in the ‘Peace and conflict’ section. There was a page on ‘Peace’, another on ‘Peacemaking’, another on ‘Pacifism’ (I’m not making this up, by the way). Then, at last, a page on ‘Holy war’. This might help us. It tells us that ‘Holy war, or Harb al-Maqadis, is only justifiable in cases where the intention is to defend the religion of Islam’. Anything on the origins of this tradition, though? Yes! Hurray: ‘Muhammad and his followers were involved in holy wars, such as the Battle of Badr and the Conquest of Makkah.’ A single sentence of actual information, within pages and pages of evasive guff.

The first half of the Christianity and Islam Revision Guide is on Christianity, the second half on Islam. The Christianity half starts with the Trinity, which is a fairly weird way to get going. Surely a quick narration of events in ancient Judea would be better, and a summary of the New Testament. A few pages on, to be fair, there is a section called ‘The last days of Jesus’s life’, with some bite-size excerpts from scripture. But there is no section on the life and teachings of Jesus – and there are 67 sections, on things like ‘Weapons of mass destruction’ and ‘Treatment of criminals’. It all seems designed to muddle and to discourage engagement with the core of this religion.

The Islam half starts even more confusingly. A section on ‘The six beliefs of Islam’ is followed by a section on ‘The five roots of Usul ad-Din in Shi’a Islam’. But there is no attempt to explain the origins of the Sunni-Shi’a split. Are the writers nervous of summarising such a controversial matter? Is this why there is no section on Muhammad?

The course is not a historical approach to the two religions, a defender might say. An online document explains that the course looks at each tradition ‘as a lived religion within the UK and throughout the world, and its beliefs and teachings on life, specifically within families, and with regard to matters of life and death’. But you can’t understand ‘beliefs in action’ unless you have a grounding in the origins and history of these beliefs.

Of course any RE textbook these days is going to avoid controversy, but this one does so in a way that is almost comical. It claims to address big topical issues, but actually teaches students how to talk harmless guff about them. In the Islam section on ‘Religious freedom’ we learn that ‘Muslims believe that having the freedom to be able to choose your religion is important’. In other humanities subjects, students are inducted into critical thought. In religion, it seems, they are shielded from it.

I have come away wondering if the teaching of RE is a good idea. If a subject cannot be taught with confidence that there is a body of knowledge worth imparting, it probably ought not to be taught at all. Better to leave religion to the priests and imams and parents, and to teach teenagers, all teenagers, very confidently about history, politics and British values.

School portraits: snapshots of four notable schools

Ludgrove, Berkshire

Ludgrove, which was founded in 1892 by the footballer Arthur Dunn, is a boarding prep school in Berkshire and has 130 acres for its pupils to learn, run around and play in. The school is one of the last preps to provide full boarding (which is fortnightly). At weekends, boys can use 11 football pitches, four tennis courts, two squash courts and a nine-hole golf course. It’s not just Prince William’s alma mater: other old boys include Alec Douglas–Home, Simon Sebag Montefiore and Bear Grylls (who opened the new Exploration Centre in June 2021). Most of the boys go on to Eton, Harrow, Radley or Winchester. The headmaster, Simon Barber, says that the school is a ‘magical place to spend five years of childhood’, and that its ‘homely environment provides a wonderful place where boys flourish and realise their potential’.

St Anthony’s School for Boys, London

St Anthony’s is a Catholic prep school in Hampstead that educates boys from the ages of two-and-a-half to 13. Situated on Fitzjohn’s Avenue, a pleasant north London street, the school says that while it is ‘primarily a Roman Catholic school, it also welcomes children from diverse backgrounds and all faiths’. The head is Richard Berlie, who says that ‘promoting a greenhouse as opposed to a hothouse environment means St Anthony’s boys are happy, hard-working and highly successful’. The school was founded in Eastbourne in 1898, but moved to its current location after the second world war. It was rated ‘excellent’ in all areas in 2019 by the Independent Schools Inspectorate. Two years ago, it was acquired by the Inspired Education Group, which owns 111 schools across 24 countries.

The American School, London

The American School, in St John’s Wood, was set up in 1951 by US BBC journalist Stephen Eckard, originally in his home and for 13 students. The school now educates 1,350 pupils – across up to 70 different nationalities – from what Americans call ‘kindergarten’ to ‘high school’. It is the only school in north London that follows the US curriculum, and a strong number of pupils go on to Ivy League universities each year. Former presidents Harry Truman, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama have all visited during stays in the UK. The school celebrated its 70th anniversary in 2021, and an Ofsted inspection in January last year rated it ‘outstanding’. The head is Matthew Horvat, who was previously Head of School at the Overlake School in Redmond, Washington.

Queen Elizabeth’s, London

It’s been an excellent year for Queen Elizabeth’s, a boys’ grammar school in Barnet. It achieved the highest performance in London for GCSE grades, with 96.3 per cent of results marked between a 7 and a 9. The school was founded in 1573 by the 1st Earl of Leicester, and was named after Queen Elizabeth I, who issued a charter ‘for the establishment of the Free Grammar School of Queen Elizabeth in Barnet’. According to the school, it ‘remains a non-denominational, non-fee-paying, selective school with a mission of producing confident, able and responsible young men’. For the headmaster Neil Enright, it is a ‘state school experience like no other’. Former pupils include Demis Hassabis, CEO and co-founder of Google DeepMind, Mustafa Suleyman, the CEO and co-founder of Inflection AI, and the influencer Jay Shetty.

Why I’ve never forgotten Sister Cecilia

It is never people, always buildings. Faces change, time blurs them, but – unless they undergo a complete makeover – buildings remain pretty much the same, bar a few coats of paint. Along the second-floor corridor lined with arched windows that overlook the street. Buses grind by below. Up the last short steep staircase and along the very top corridor, which is narrower and lined with books. They call it the library and I am often here, tucked into the window seat reading, but otherwise heading for the arched door – everything is arched here – at the far end. It opens on to a low-ceilinged room with roof lights through which the sun seems always to be shining. Wooden floor, tall cupboards and shelves housing drawing boards, reams of paper – cartridge paper, sugar paper, Kraft paper, A1, A2 – boxes of pens, crayons, chalk, charcoal. Scissors, tables, easels, guillotines, standing desks. Not many chairs, just low benches.

Paintings, drawings, pinned to the wall on cork boards, sketches of ballet costumes, portraits, bunches of wild flowers, individual petals and leaves, every thread of vein outlined, the tops of roofs and the spire of the church on the hill behind.

The art room. The quietest, calmest, most peaceful room in the whole large convent school, the room where every worry and fret and problem falls from your shoulders and any scowl or frown is smoothed from your face as you enter. Even time stops and ceases to matter.

It is best of all when Sister Cecilia is here, at her table in the corner with light falling on to her drawing or painting, collage or embroidery, or tiny papier-mâché model of an animal, a statue of the Virgin Mary, the Vatican, a ship with cotton sails. Sister Cecilia, tallest of the community of nuns, with their heavy black woollen robes and white wimples, big wooden crucifixes around necks, rosary beads clicking softly as they move about. Whatever stories are told about nuns – bitter, warped women with cruel, repressed minds and hollow hearts – I only knew one in my entire convent education who fitted that particular bill, but the saintly, happy, loving presence of Sister Cecilia more than cancelled her out.

I get the feeling Sister Cecilia would not have liked felt-tips. Too superficial. Too glib

I loved her. We all loved her because she loved us and all her fellow nuns too, and the convent cat and the birds in the garden. She was carved and formed out of love. I wondered about her then, and I still do – where she had come from, why she was there, what her life had been before taking religious vows. She would never see her family again, unless an immediate relative died – a parent or sibling – and then she would be allowed to travel accompanied by another sister.

But there was no bitterness or even sorrow in her. She was serene, she could laugh until the tears rolled down her cheeks and she had to fetch a hankie from somewhere in the voluminous depths of her habit. She was always full of praise for our artwork, making simple, spot-on suggestions for transforming, alterations and improvements, basking in the sun shining on her head like a halo. And a halo was way less than she deserved.

I was not especially good at art, but Sister Cecilia made me feel that one day I might be. I loved to watch her pick up a B4 or a scraping of charcoal and, with the three or four swift lines and a light rub, turn it into a thing of interest, even beauty. ‘Ask it a question,’ she would say, touching one’s paper. ‘Look at it and let it tell you. Listen as well as look. And don’t rush.’

I only learned how to draw one thing, from the dozens of little tricks she taught us about making a mark on paper become whatever you wanted. I can still turn an ‘8’ into a fish. I can create shoals of tiny 8s to fishes, swimming across a page, and in idle moments, do. If I have a handy felt-tip I colour them in, though I get the feeling Sister Cecilia would not have liked felt-tips. Too superficial. Too glib.

I had some very good school friends – one of whom I still have, almost 80 years after we met walking in at the kindergarten entrance together. As in every school, perhaps more markedly so then, there were some good teachers and a few bad, and one sadist. Maybe I will bring myself to write about her some day. But because there was also Sister Cecilia, one saint, loved and loving and wholly good, there was protection. Her art room was a haven, a quiet place of happy creativity, a refuge from noise, lukewarm cabbage and maths. I could have lived there. I never wanted to go home.

Does might make right?

The criminals Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin both believe that might is right. The whole question fascinated the ancient Greeks.

In his famous history of the long war between Athens and Sparta (431-404 bc), Thucydides (d. c. 400 bc) explored the question through speeches on both sides, but on one occasion – when Athens demanded the surrender of the small island of Melos – he put it in the form of a debate. Here is an edited sample, strangely apposite too:

Ath: You know as well as we do that, in the real world, justice comes into it only between equals in power, while the strong do what they can and the weak have to comply.

Mel: But we think it is to our advantage – we speak as we must, since you compel us to forget about justice and talk only of interests – that you should not destroy a universal good, that is, for those in danger to invoke what is fair and right. This applies no less to you, as your fall would entail the heaviest vengeance.

Ath: … We want to make clear to you that we are here in the interests of our own empire, yes; but what we shall say is designed to save your own city. We wish to take you under our rule without trouble: it is in both our interests that you should survive.

Mel: And would it be an advantage for us to be enslaved as much as for you to rule over us?

Ath: Certainly, because we both benefit: you by surrendering before experiencing the worst of consequences, and we by your survival.

Mel: So you would not consent to our being friends rather than enemies, allies of neither side?

Ath: No: to our subjects, friendship signals weakness, and your hatred, proof of our power… This is not a noble struggle between equals. You are debating your very existence.

And so on. The subtext of all this is: it’s only results that count – a very Greek view of the world – and what was the result? Sparta won the war. By the way, Socrates argued that might was not right. What was right was justice. And we all know what Trump and Putin think about that.

The cat that tamed Dom

I don’t like cats. I don’t like their reptilian stealth, or the way their heads are set low and poke out from their bodies. I don’t like the constant showing off of their puckered bums, or their disregard for the normal rules of mammal eye contact.

There are nearly 13 million cats in Britain – one in three of us owns them. There are roughly 74 million in the United States and until recently I found it inexplicable. Why would anyone choose to love and nurture a psycho that dismembers songbirds, often torturing them first in a casual, playful way? I’ve enjoyed in the past writing about the idiocy of ethical vegetarians who own cats. And I would, in different circumstances, be keen to stick it to cat owners again over the news that cat fur, treated with chemical flea-killer, could be partly responsible for the terrible decline of birds worldwide. The birds use the fur to line their nests and the baby birds are slowly poisoned by it before they ever even take flight.

But now George has arrived, and I’m hobbled by my own hypocrisy.

George is a large grey kitten with disproportionately big ears and I didn’t plan for him or want him. He appeared on my neighbour’s doorstep one morning, squashed into a shoebox with his tiny sister, both about three months old and dozy from lack of oxygen. While my neighbour worked out what to do with them, she invited my son and me in for a look, and if I had to pinpoint the moment that the cat started messing with my mind, it was probably right there and then. George waved his grippy little paws about and climbed on to our knees.

I wasn’t especially moved but nonetheless, to my surprise, I found myself saying that we’d take him. This made no sense as a decision. We had travel plans. My husband loathes cats. But I said it, and now that George has been with us a while I’ve begun to understand why. I’ve begun also to see how cats have been able to dominate the internet and infest every form of social media. Lost cats, missing cats, cat care, cat memes, cats in bonnets, cat cartoons, cat anime, cat crypto.

Why would anyone choose to love a psycho that dismembers songbirds, often torturing them in a casual way?

The answer is that cats are not normal animals, but best thought of as fur-coated viruses designed to manipulate the human brain. Consider the ease and the speed with which George captured my husband. Dom is a kind man but his feelings about the politicians he often works with are not kind. In the pre-George era, his usual monologue, reading the political news of the day, went like this: ‘Gah! Bastards. Clowns. Idiots.’ Just 24 hours after George arrived, it took a new turn: ‘Gah! Bastards. Clowns. Idiots… Oh, hello kitten! What a lovely kitten! What a brave and perfect kitten!’ Then back to the clowns and idiots.

It’s bizarre. Sometimes, in a moment of quiet, I catch Dom and George staring solemnly and seriously into each other’s eyes. It’s love – or perhaps it’s just the cat updating the software it’s installed. Who knows.

I’m serious about this. It’s a real theory. After all, there are several examples of inter-species mind-capture that occur naturally in the wild. Perhaps you’ve read about Toxoplasma gondii – T gondii if you’re feeling affectionate – a parasite that infects rats but must inhabit a cat to reproduce. To get to its happy place inside a cat, T gondii changes a rat’s behaviour, turning its natural fear of felines into a desperate need to be loved by them. Even the smell of cat urine becomes suddenly irresistible to a gondii-fied rat. It’s drawn to the cat, its heart full of passion, and then the cat eats it.

I love George. Of course I do. I’ve been gondii-fied too. But I can see how cat tricks work. We know already that cats are neotenic– that is, they have evolved to look overtly infantile. Their huge wide-apart eyes and flat faces are optimised not for preying on mice so much as for preying on the instinct we have to nurture our own young. We also know that a cat’s miaow is just for human benefit. It’s not a natural noise for a cat. Lions don’t miaow. Cats don’t communicate with each other in miaows. They’ve cooked up the sound in order to mimic a human baby’s cry.

As it happens, I’ve also noticed over the weeks we’ve had him that George’s miaow has also adapted to his environment. What was once a thin whine now has a rounder vowel sound. Mouuuuuuw! Last Wednesday I heard my son crying out for me at around midnight: ‘Mu-uum!’ I ran upstairs to comfort him but found him sound asleep. George on the other hand was wide awake on the top stair, looking like a cat whose plan had come together nicely. At night, I shut the bedroom door on him, but whenever I open it, whatever the time, there George is sitting, staring straight ahead with his black grape eyes, biding his time. The day will come, he believes, when he sleeps next to Dom.

Over the weekend, having never meant to let George into the garden, I found myself putting him in a cat harness I’d somehow bought online, letting him roam about on a long lead in the sunshine. When a family of joyous long-tailed tits flitting about in the garden saw George, they began a series of shrill alarms. George eyeballed them and chittered with bloodlust, like Hannibal Lecter recalling a human liver. Then he leapt at them, fangs bared, before being pulled short mid-air on his lead.

The lead is not a sustainable solution. I can see that. Summer is coming. Given the scorn I’ve poured in the past on cat owners, it would be astonishing and morally indefensible for me ever to let George loose to murder tits and sparrows in nesting season. But am I a match for the virus? Only a fool would bet against a cat.

Event

Spectator Writers’ Dinner with Matthew Parris

Senior service

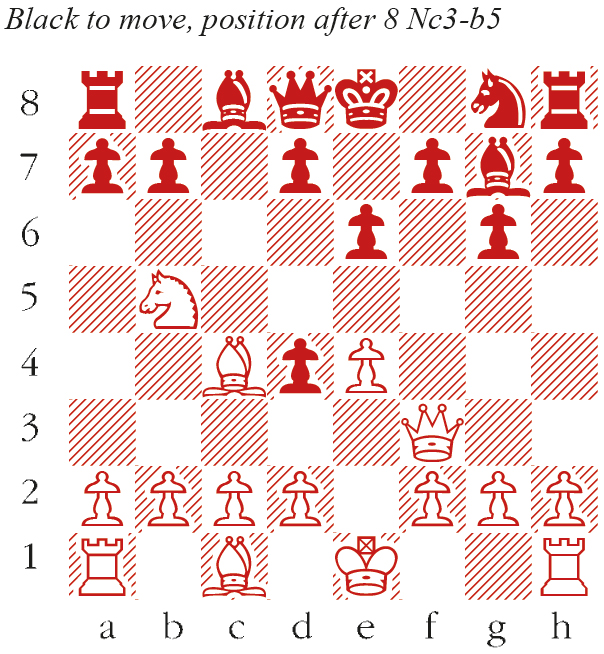

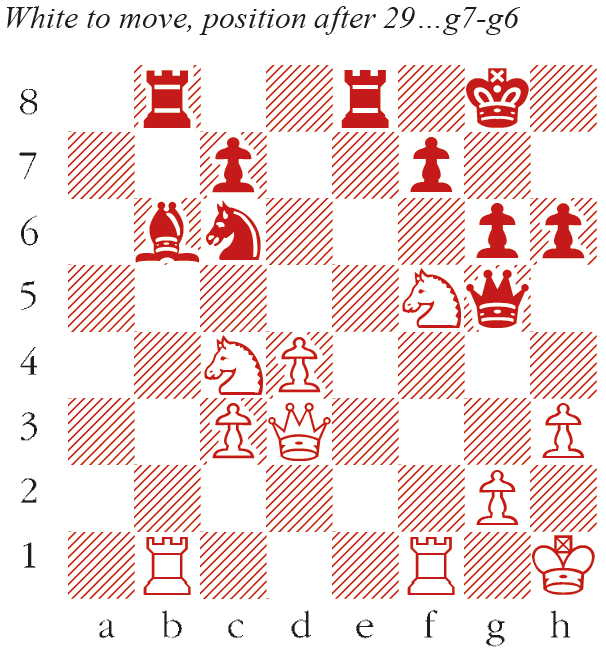

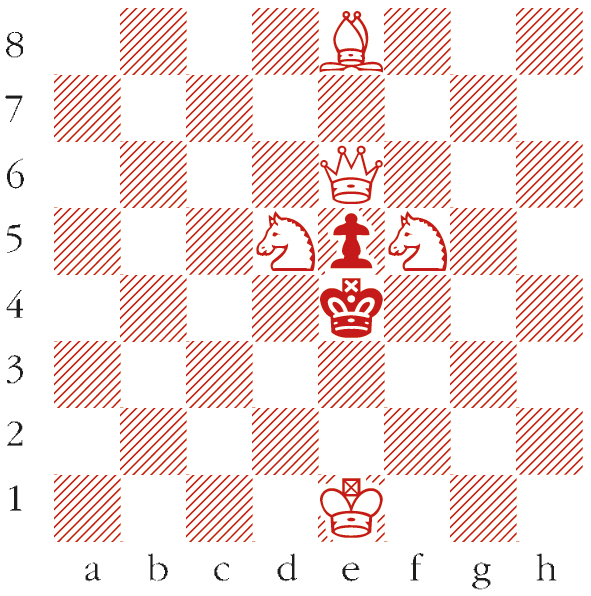

England’s over-65 team triumphed at the World Senior Team Championships, held in Prague last month. They began this event as second seeds behind the German team Lasker Schachstiftung, whose strongest player Artur Yusupov, originally from the Soviet Union, was once ranked third in the world. That crucial England-Germany match ended in a 2-2 tie, but England’s team of John Nunn, Glenn Flear, Tony Kosten, Peter Large and Terence Chapman scored more consistently against the rest of the field, helped by an outstanding 7/8 score for Peter Large.

In the game below, his primitive threat to the f7-pawn at move seven bears a funny resemblance to Scholar’s mate, which arises after 1 e4 e5 2 Qh5 Nc6 3 Bc4 Nf6?? 4 Qxf7 mate. Early queen development tends to backfire, as a decent player will parry the threat and later harass the queen. But Large’s move, used in many master games, is a venomous exception.

Peter Large-Leon Lederman

Fide World Senior Team Ch, Prague 2025