-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Shakespeare as cruise-ship entertainment: Jamie Lloyd’s Much Ado About Nothing reviewed

Nicholas Hytner’s Richard II is a high-calibre version of a fascinating story. A king reluctantly yields his crown to a usurper who wants his violent revolt to seem like a peaceful transfer of authority. This delicate, complex narrative is presented as a boardroom power struggle in corporate Britain. Snappy suits for the dukes and princes. Commando uniforms when they take to the battlefield.

Jonathan Bailey (Richard) starts as a swaggering, coke-snorting yuppie who dreams of extending his realm overseas with someone’s else money. Disaster strikes, the crown slips. Calamity sharpens his awareness and he becomes a lyrical philosopher who laments the bewitchments and pitfalls of power. Bailey’s charming, easy-going Richard brilliantly traces the character’s journey from glib party-lover to meditative hermit.

The modern stylings don’t work perfectly. The ‘sceptred isle’ speech sounds banal when delivered by John of Gaunt slumped in an NHS wheelchair. The battle scenes are marred by plastic detritus scraped from a landfill site. And the musical soundtrack surges and fades at random, as if it had a mind of its own. Here’s an idea. If you don’t notice the soundtrack, it needn’t be there. If you do notice it, it shouldn’t be there.

The second half includes two passages of heartbreaking comedy. Richard and Bullingbrook tussle physically over the gold crown like brothers unable to share a box of Quality Street. Later, Michael Simkins and Amanda Root (as York and his wife) beg the new king to spare the life of their wayward son. On their knees, they hobble around the castle floor, pleading and weeping. Tragedy is gloriously fused with absurdity here.

This show is an ideal starting point for Shakespearean newcomers. The play is easy on the eye, always absorbing, simple to follow. And the Bard speaks to us loud and clear. That really matters. Too many Shakespearean productions these days are barmy experiments put together by dogmatic fetishists for their own amusement.

Much Ado About Nothing, directed by Jamie Lloyd, is a case in point. Never mind the script, let’s have an acid-house party. The stage is empty apart from a few office chairs and a plastic crimson heart the size of an ice-cream van. Blizzards of pink confetti fall non-stop, smothering the stage, gathering in drifts, forming hillocks which the actors romp and frolic in. The show offers very few links to Shakespeare’s poignant story about a romance that blossoms in the aftermath of war. The lovers, Beatrice and Benedick, are versions of each other, broken-hearted clowns who use verbal swordplay to hide unknown and unexplained sources of anguish.

The play is easy on the eye, always absorbing, simple to follow. And the Bard speaks to us loud and clear

Does that interest anyone here? Not really. Instead we get a song-and-dance pastiche dominated by club music and cheap clothes from a joke shop. Nasty colours too. Garish blues, livid scarlets, clashes of pinks and browns. The prankster in charge of the costumes has at least spared Tom Hiddleston (Benedick) and Hayley Atwell (Beatrice) from the worst humiliations. The stars look pretty good. He’s in a navy-blue shirt and matching trousers. She wears a glittery jumpsuit held at the waist by a tight scarlet belt. They dance constantly, endlessly, boringly. Atwell poses and twerks like a dehydrated teenager at a rave. When she speaks, she rushes her lines, garbling too many of Beatrice’s subtle and gleaming gems. Unless you know the part well, you’ll miss much of the heroine’s gorgeous, silvery wit. Hiddleston entertains his fans with a corny menu of stripagram routines. He thrusts his pelvis at the crowd. He dry-humps imaginary lovers. He twirls his loose belt around his finger like an unattached Hoover nozzle. Throughout these Chippendale sections, he smirks, nods and winks at the crowd. Shakespeare seems barely an afterthought.

The scenes in the first half are done like skits for a Comic Relief show. The awkward and tender moment when Beatrice invites Benedick ‘to come into dinner’ is ruined by Hiddleston who rips his shirt open in the middle of the dialogue. Sheer vandalism.

Never mind thescript, let’s have an acid-house party

In the second half, the plot grows darker and the show reaches for shades of melancholy that it can’t find. Perhaps that’s not the point. The cheesy energy and the soft-porn details seemed to delight the crowd on press night when the stalls were crammed with hot-flush mums, swooning gay men and adoring celebrities.

Let’s be fair. This show is a big improvement on Jamie Lloyd’s bizarre and depressing version of The Tempest at the same venue. This is fun. The cast have a great time. It’s perfect entertainment for anyone wanting to see two off-duty movie stars pratting around on stage for a couple of hours and reciting the odd dreary speech by some dead bloke written in obsolete English. Purists, stay away. This is an earnest attempt to bring Shakespeare down to the level of cruise-ship entertainment. Mission accomplished.

Who’d be in the Jailhouse of Commons?

Picking a pope

To choose a new pope, 120 cardinals will be confined in the Vatican until they have reached a decision. To pick Pope Francis in 2013 took two days – but in November 1268, when cardinals gathered in the town of Viterbo to choose a successor to Clement IV, there was deadlock. Locals locked the cardinals in the episcopal palace and even removed the roof to speed them up. It still took until September 1271 to pick Teobaldo Visconti, who became Pope Gregory X.

Jailhouse of Commons

Ex-Labour MP Mike Amesbury was jailed for assault. In a House of Commons made up of MPs and former MPs jailed since 1945, who would form the government?

Labour (Amesbury, Raymond Blackburn, David Chaytor, Terry Fields*, Eric Illsley, Elliot Morley, Fiona Onasanya*, John Stonehouse, David Weitzman*) 9

Opposition Unity (Northern Irish party) 8

Conservative (Jonathan Aitken, Jeffrey Archer, Keith Best, Peter Baker*, Bill Carr, Ian Horobin, Imran Ahmad Khan) 7

Ulster Unionist 7

Democratic Unionist 6

Lib Dem (Chris Huhne) 7

* Jailed while still a sitting MP

Streets ahead

According to estate agents Savills, the value of residential property in the UK has reached £9.1 trillion, 3.5 times GDP. How is this spread around the country?

London £1992bn

South East £1698bn

East £996bn

South West £847bn

North West £720bn

West Midlands £632bn

Scotland £546bn

East Midlands £520bn

Yorkshire and Humber £508bn

Wales £302bn

North East £191bn

Northern Ireland £153bn

Renewed effort

The Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit claimed the UK ‘net zero sector’ employs 951,000 people and has expanded by 10 per cent in a year. How does Britain compare internationally for renewable jobs? Number employed in 2024 according to the International Renewable Energy Agency:

China 7.39m

Rest of Asia 2.16m

EU 1.81m

Brazil 1.57m

US 1.06m

India 1.02m

UK 57,000

I was told I was too middle-class to adopt

Too many books? Yes, we had too many books. That’s what our social worker told us when we were being assessed to see whether we were suitable parents to adopt a baby from China back in 1996. It seemed to us, a middle-class, well-educated couple, an extraordinary statement and so it appeared to our friends and acquaintances. But that was, and is still to some extent, the credo at work in assessing potential adoptive parents.

A significant number of social workers continue to believe that a child should be matched as closely as possible with the social class and ethnic background of the adoptive parents, even if that means children being held in institutional care far longer than is good for them. An adoption textbook, published in the 1970s but still being used in the late 1990s, has the following advice, which has endured: ‘Where the choice is between the foreman of a factory and the managing director, all other things being equal, we would favour the foreman as an adopter.’

We took the agency that turned us down to a tribunal and won the right to be assessed by a second one, which approved us. Three-and-a-half years after our first letter (what my husband called an ‘elephantine pregnancy’), we finally brought our daughter home.

The world has moved on since the 1990s. China closed its doors to overseas adoption last November after 32 years. This followed the abandonment of the one-child policy, introduced by Deng Xiaoping in 1979 to ease an exploding population, which resulted in tens of thousands of baby girls being left in fields, parks or outside orphanages.

China now has an ageing population, with more boys than girls. And China’s loss was the West’s gain. There’s now a diaspora of young ethnically Chinese people all over the United States, Europe and Britain, who were part of the estimated 160,000 or so babies adopted in western countries during that time.

The one-child policy was first eased in 2015, when the Chinese government decreed that couples could have two children, raising the number to three in 2021. Not that modern Chinese couples are enthusiastic about the prospect of bigger, more expensive families, but that’s another story.

The process of adopting babies and toddlers in this country is subject to damaging delays

Yet while China has stopped allowing overseas adoption, there are still many countries with children in need. The leading countries putting children up for adoption today are India, Colombia, Bulgaria, Haiti and Nigeria. Bizarrely, for those who think public policy should be consistent, social worker attitudes about interracial and inter-class adoption within the UK seem to go out of the window if people look for children overseas – although an assessment still must follow most of the guidelines applying to a UK adoption. It’s an anomaly that nobody seems able to explain.

Back in Britain, the number of babies available for adoption has dropped to the low hundreds. More single women now keep their children and bring them up alone. Any babies given up these days are, quite rightly, adopted by young couples, with 40 as the unofficial cut-off age for adoption of children under five.

But even the process of adopting babies and toddlers in this country is subject to damaging delays. One white couple who recently adopted a white baby girl told me she had been abandoned at birth but placed in a foster home and only approved for adoption a year later. These kinds of delays can be even longer where couples or single adopters want to adopt a British child of a different race, despite repeated attempts to speed up the process.

In theory, the Adoption and Children Act 2002 eased the strictures on interracial adoption. Its intention was that although a child’s racial and cultural origins were relevant factors, ‘a child’s ethnicity should not be a barrier to adoption’. But concerns persisted that racial differences were still preventing children of different backgrounds from being placed with families.

This issue was highlighted in 2012 by The Spectator’s editor Michael Gove when he was education secretary. ‘It is outrageous to deny a child the chance of adoption because of a misguided belief that race is more important than any other factor,’ he said. ‘And it is simply disgraceful that a black child is three times less likely to be adopted from care than a white child… I promise you I will not look away when the futures of black children in care continue to be damaged.’ In 2014 the Tory-Lib Dem coalition government confirmed that ‘a child’s ethnicity should not be a barrier to adoption’. Even so, some social workers appear to be fighting a rearguard action. They believe that the adoption of poor children by middle-class parents is ‘social engineering’, which they say contravenes the European Convention on Human Rights in relation to class discrimination and the right to a private and family life.

Such views still influence adoption decisions, whatever the government might decree. One white couple told me that their social workers would not match them with a black or mixed-race baby unless they could prove they had close African or Afro-Caribbean friends.

This might just be understandable if the number of children in care in Britain were not a dire problem. In March last year, 83,630 children were in local authority care, of which two-thirds were with foster carers. Only 2,980 children were adopted during the previous year, while 5,880 were awaiting adoption.

The problem is still particularly severe for non-white children. Although 29 per cent of children in care are from ethnic minorities, they make up only 16 per cent of adoptions. Perhaps the biggest scandal of all is the time between a child entering care and being placed with an adoptive family. Last year the average was 883 days – or more than two years and five months.

There is still much room for improvement. To help raise awareness of these issues, I have written a play drawing on our struggles as a middle-class couple looking to adopt a child. Called Too Many Books, it is a work of fiction, but it’s informed by our and others’ experiences in treading through the treacle that is the British adoption system.

What Europe gets wrong about the far right

The head of America’s ‘Department of Government Efficiency’ (Doge) has written to all federal workers in the US asking them to explain in a brief email what they did last week. The exercise is intended to take no more than five minutes but has already lead to howls from many employees. How could anyone expect them to perform such a task? How can one explain the intricacies of supporting transgender opera among the Inuit in such short order?

Happily, the new editor is not putting those of us on The Spectator’s payroll through any similar exercise. Nevertheless, something in the global vibe-shift perhaps impels me to mention a little of what I have been doing with my time. And the first thing that comes to mind is that while everyone else is swimming in a sea of acronyms, I might have something useful to say about the recent elections in Germany.

It has been my view for a very long time that most mainstream press coverage of politics on the European continent is pretty much bunk. I arrived at that realisation after a period of some years when I was in a different European country most weeks, meeting with politicians and trying to work out who was who. There was a time when a lot of the media did that: within living memory British tabloids had correspondents in all the major European capitals. But today even the broadsheets have gone over to impossibly wide-ranging roles like ‘Europe correspondent’, which is only marginally more useful than the BBC’s ‘Africa correspondent’.

Another problem is that the few outlets that aspire to actually cover politics in Europe are prone to a law of British journalism which must someday be analysed. This is the presumption that all left-wing parties (such as the charming government of Spain) should be assumed to be doing a jolly good job and be allowed to get on with it. By contrast, any centrist political party is to be deemed under caution unless it backs all the major left-wing causes of the day. And any right-wing party – including any that might dare just to be ‘conservative’ – should be treated as though it is about to usher in the second coming of Adolf Hitler.

The AfD did not manage to‘march to power’. But it diddouble its share of the vote

Personally, I have always found this a charming foible of the left-wing media. They are all for internationalism, fraternity, unity and so on, but seem to believe that most foreigners – certainly in Europe – are fascists in barely concealed disguise. And this interpretation of Europe seems to have lain behind most of the coverage of the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party, both before and after Sunday’s federal election in Germany.

Some prominent non-Germans have taken the side of the AfD of late, on the apparent presumption that anyone who has been anathematised to such an extent must be good. But as I tried to explain to some of the American media this past week, the truth is that the AfD is a curate’s egg (a phrase that led to some of my American readers frantically googling).

However you phrase it, the idea that the AfD might be good in parts remains too subtle a point for much of the media in Germany and beyond. On one side are people rightly fed-up with cancel culture and name-calling and mainstream politicians ignoring the views of the public. They then react further to the large number of commentators desperate to write pieces with headlines like ‘Far-right rises in Germany’.

Yet many of the AfD’s policies are perfectly commonsensical. It is not as though the centrist parties have managed to get control of mass migration, to name just one form of political rocket-fuel. So if a party comes along that says it would really like to tackle immigration and stop the emerging new traditions of car-rammings and knife attacks then ordinarily they’d be credited with something. But modern European politics doesn’t work like that.

Several things make this even more complicated. Geert Wilders now heads the largest political party in the Netherlands. But some 20 years ago, when I first interviewed him in his office in the Dutch parliament, he was the only member of his party as well as its sole MP. He was the only member because, as he admitted, if any right-of-centre party starts up in continental Europe it will be called far-right by the media and its opponents. The small number of actual far-right types who still exist will then be the first to join – so destroying the party from the get-go. There is no reason why politics should be dictated or destroyed by such extremes. But that is how it goes. And this is how much of the political mainstream and activist left are actually happy for things to go.

Which brings me back to the AfD. As the election came closer there was much excited talk about how the party would storm the polls. The party encouraged some of this, as did its political opponents. And the problem upon a problem is that, as the party has grown some very unsavoury types have indeed muscled into the AfD. The wiser party leaders spend a large amount of their time making sure to sideline or expel such people. That is a full-time job. But it is also a piece of political brain surgery at which many people would like to see the AfD fail.

If they do fail, to say that would be a catastrophe would be an understatement. A right-wing party in Germany of all places actually turning far-right would spell a nightmare for everyone.

The AfD did not manage to ‘march to power’ this week. But it did double its share of the vote from the last election. A wise mainstream would notice this and decide (as the Danish centre and left have) that sometimes you should listen to the public and adapt your policies accordingly. But most countries do not seem to have a wise mainstream. And so the problem will be put off until everything is worse.

Make Bond great again

One of the great recurring James Bond tropes is to make it look as though 007 has actually been killed before the film’s title credits. You Only Live Twice, From Russia with Love and Skyfall all begin with Bond in a position where his demise seems inevitable. Of course, he always turns up alive. (Quite what the rest of the film would consist of if he didn’t is anyone’s guess: perhaps Moneypenny dealing with probate or M arranging one of those ghastly direct cremations.) Now, however, we may have reached a danger from which even Bond cannot wriggle out.

Amazon, the company responsible for one of the biggest flops in TV adaptation history, the Middle-earth prequel series The Rings of Power, has paid more than $1 billion to take ‘creative control’ of the Bond franchise. This is a bit like the White Star Line sending a telegram to the bottom of the Atlantic to ask Captain Smith if he’d like a second crack at the old ocean-liner gig. Still, this needn’t be the end of the Bond we have known and loved. If Amazon can learn from its mistakes, and really try to understand what fans long for, our man may yet live to die another day.

The first and most important lesson: don’t hire people who fundamentally hate the source material. This is essential to all decent adaptations. Peter Jackson’s passion for Tolkien’s world and lore shines through in every scene of the Lord of the Rings films. Recent Bond adaptors have shown no such affection. Cary Fukunaga, the director of Daniel Craig’s execrable final outing, No Time to Die, described Sean Connery’s 007 as ‘basically a rapist’. Craig made no secret of being there under sufferance, saying in 2015 that he’d ‘rather slash [his] wrists’ than reprise the role. As the YouTube reviewer The Critical Drinker put it: ‘Jesus Christ, dude, you must be the only man on the planet who doesn’t want to be Bond.’

To my mind, any new Bond film should also return to traditional self-contained storylines rather than seeking continuity between instalments. With standalone plots, the occasional dud outing can do only so much damage. One reason why later Craig films never lived up to the triumph of his debut, Casino Royale, is because each new instalment was dealing with the detritus of the last one: Quantum of Solace picks up where Casino Royale left off and the film’s plot (such that it is) doesn’t get going until halfway through. My theory for the Hamlet-level bloodbath of beloved characters by the end of No Time to Die (the film not only kills off Bond but also his great ally Felix Leiter and his arch-enemy Ernst Stavro Blofeld) is that this was quite simply the only way to reconcile all the unresolved plot strands.

I yearn for a Bond who looks like he might enjoy a proper lunch rather than a diet of protein shakes

The series also became tediously self-referential – endless ham-fisted explanations for Bond’s continuing relevance, with everything a metaphor for Britain in decline (yawn). Skyfall even took a potshot at fan-favourite GoldenEye. ‘Is this it?’ says Bond, bemoaning his pared-back gadgetry. ‘What did you expect?’ replies Ben Whishaw’s Q. ‘An exploding pen?’ (Well yes, actually!) The Craig era wanted you to take it incredibly seriously. Spectre smugly named its heroine Madeleine Swann after two Proust references. Nowadays, Bond girls probably can’t be called Ivana Humpalot, but there must surely be some compromise between this and the sanctimonious Bond we’ve suffered in recent years. A return to fun, camp enjoyment and a sense of humour, will be vital. Perhaps even – God forbid – the occasional bit of shagging.

Many modern Hollywood instincts should also be ignored. Thanks to the glut of superhero films, actors are expected to be unfeasibly jacked. Sean Connery was a professional bodybuilder before he played 007, yet he’d barely be considered muscular by today’s film standards. We don’t need Bond looking like he’s one steroid injection away from his heart exploding, especially when fine dining is such a staple of the Fleming books. It may seem a small thing, but I yearn for a Bond who looks like he might occasionally have enjoyed a proper lunch; four courses plus savoury at Boodle’s, rather than a diet of protein shakes.

Finally, the films should return to tracing actual geopolitics. In the past, the East-West struggle grounded Bond in political reality, even if the film indulged in campery along the way. The thawing relationship between Bond and KGB boss General Gogol in the Moore/Dalton era mirrored détente and the fall of the Iron Curtain. Dr Kananga of Live and Let Die bears a striking resemblance to Papa Doc Duvalier; Licence to Kill’s drug-lord Franz Sanchez to Pablo Escobar. Media mogul Elliot Carver from Tomorrow Never Dies was clearly based on Robert Maxwell. Even Die Another Day takes place in North Korea.

Recent films have dispensed with such specifics in favour of vaguely defined hacker groups or rogue agents from Bond’s past. Villains tend to be nebulous figures of unspecified nationality, presumably to avoid offending the sensibilities (and wallets) of ‘international audiences’. As geopolitics became deliberately vague, identity politics took its place. Consider the fleeting reference to Q’s sexuality in No Time to Die; he is outed in a throwaway line, enough to burnish the progressive credentials of the writers’ room while remaining sufficiently brief to be easily edited out for screenings in China and the Middle East.

It ought to be a no-brainer to find a place for Bond in the current geopolitical melange. If you can’t have Russian baddies now, when can you? Equally, we don’t have to imagine a shadowy communist super-state which seeks to undermine the West. It exists and is called the People’s Republic of China. However, given changes across the Atlantic and the nationality of the people most likely to ruin Bond this time around, perhaps his next foe will be an American.

Are you Ramadan-ready?

‘Are you Ramadan-ready?’ That was the poster in Sainsbury’s advertising its delicious range of fast-breaking foods (rice was one). And the striking thing about it was… the ‘you’. That ‘you’ means the normal customer, the default Sainsbury’s shopper.

Same with the email I got from the swanky Belgravia hair salon I used to visit:

Here, we understand that Ramadan is a time of reflection, renewal and spiritual focus – and we also know how important it is to take a moment for yourself amid the busy days of fasting and prayer. That’s why we are delighted to announce that our salon will be open late during Ramadan, offering evening appointments so you can indulge in a little luxurious self-care after Iftar [the fast-breaking meal after sundown].

Belgravia is next to Knightsbridge where wealthy Arabs are the norm, so the email wasn’t surprising – but again, the odd thing was that ‘you’: the assumption that the recipient is more likely than not to be Muslim. Naturally, if I’d got an email in April saying ‘Are you Easter-ready?’ I would have regarded it as par for the course – though, come to think of it, I’d probably have been a little surprised. Harrods is offering Iftar dining on its website: ‘Tuck into an Iftar feast, starting with Medjool dates accompanied by a refreshing hibiscus cooler.’

But then Ramadan, which starts this week, is now very much part of the calendar, much more than, say, Diwali. For the third year there will be a switch-on of the Ramadan Lights in London – previously on Oxford Street, this year in Coventry Street, where the message will be ‘Happy Ramadan’ until it changes to ‘Happy Eid’. (Have you noticed the asinine default greeting is Happy Everything, from Halloween to Fridays?)

Once again, it’s the assumption that we’re all up for it that’s a little curious. Ramadan Lights is supported by the Aziz Foundation which is also running an Iftar Food Trail where companies such as Shake Shack and Bone Daddies will be offering special Ramadan treats and discounts. In Leicester Square there’s an interactive light installation where visitors can press a button ‘to send beams of light soaring up the structure, visually representing the Spirit of Ramadan’.

Schools, too, are very much Ramadan-conscious. Several London boroughs have issued guidance to schools about how to do the season. Wandsworth, for instance, advises them to ‘take care in the timetabling of activities that no pupil who is fasting is required to do anything that would make her/him break the fast or become dehydrated or weak. This could include swimming, strenuous physical exercise or tasting food in food technology/cooking sessions’. Further, schools should use ‘Ramadan positively… by holding assemblies about it’. Which means, I suppose, that all pupils will be following the same framework.

This is pretty predictable in a society which is significantly less Christian than it used to be – fewer than half of us say we’re Christian – and with a large Muslim component: at least 6 per cent in the country and 15 per cent in London, according to official figures. But it’s still oddly unsettling that Islam is now the default ‘us’.

I’d be less conscious of it if it weren’t that the Christian equivalent, happening at the same time, is so very much off the radar. Lent, as we used to know, is the Christian equivalent of Ramadan and it starts next Wednesday. That begins the 40 days before Easter of fasting, abstinence and good works which is, as I never tire of pointing out, a much better time for giving things up than bloody Dry January.

How many schools are marking Lent, offering fish on Ash Wednesday, asking pupils what they’re giving up, or doing an assembly about the ash crosses on Christian foreheads? We’re pretty good about Shrove Tuesday as an excuse for pancakes, but it only makes sense as a pre-Lent thing in that the batter uses up the dairy and eggs that we once renounced for the next 40 days. A while back I suggested to a newspaper that I should write about giving up things for Lent. The editor looked baffled: ‘Why on earth would I want to read that?’

There are any number of elements of the Christian year that we’re too ignorant or indifferent to mark. What about Whitsun/Pentecost, previously quite a big deal? Remember Good Friday? But we can hardly blame Muslims if Ramadan and Eid are edging Lent and Easter off the calendar. Unless Christians, including those calling themselves cultural Christians (i.e. those who can’t be arsed to go to church), actually make a big deal about our feasts and fasts, we can’t expect others to take them seriously either.

The Roman approach to ending a war

We await the full details of Donald Trump’s ‘take it or leave it’ solution to the Ukraine war, but at least Romans liked that sort of clarity. Take the war between Rome and the Carthaginian Hannibal, begun in 218 bc.

Rome had already defeated Carthage in a long drawn-out battle over the possession of Sicily. In search of revenge, the father of young Hannibal made him swear never to befriend Rome. His family conquered southern Spain, rich in silver mines, agriculture and manpower, and when in 219 bc Hannibal sacked Saguntum, a town allied to Rome, Rome sent an embassy to clarify the situation. The Carthaginians complained of Roman treachery and asked what they wanted.

According to Livy, the Roman statesman Fabius ‘laid his hand on the folds of his toga gathered to his breast and said: “Here we bring you peace and war. The choice is yours.” At once came the reply: “Whichever you want: it is all the same to us.” Fabius dropped the folds and said: “We give you war.”’

Another example: in 202 bc Carthage was defeated, and Rome turned to punishing Carthage’s allies, one of whom had been King Philip V of Macedon. In 168 bc, after Philip’s death, Antiochus, the Greek king of an empire from Turkey to Iran, decided to intervene on the Greek side. His first target was Egypt, long a Roman ally. But there a Roman envoy, Popillius Laenas, met him and ordered him to withdraw, or it was war. Antiochus said he would take advice. Popillius used his staff to draw a circle around him in the sand and said: ‘Give me your reply before you step out of this circle.’ Antiochus thought about it and agreed to pull out.

So, around whom will Trump draw the circle – Volodymyr Zelensky or Vladimir Putin – and with what aim in view? Given that Putin’s economy and army are broken (anyone seen a Russian plane or helicopter recently?), Trump could deal a death-blow to Putin’s ambitions and perhaps see him gone. Or, as Trump is contemptuous of the EU and Zelensky, he could tell them to sort it out. The power and responsibility lie with Trump. He will certainly not get a Nobel Peace Prize without considering the international implications of his decision.

The great betrayal of the SAS

We should all feel scared to our bones about the persecution of the SAS, soldiers harried through the courts for jobs they did many decades ago. It’s not that the SAS should be allowed to behave like trigger-happy psychos, but as Paul Wood wrote in this magazine before Christmas, Special Forces are now being hounded and punished for simply following orders and conducting operations. And what will we soft sofa-sitters do when no one wants to be a soldier any more?

Wood described in particular the plight of 12 soldiers of a Specialist Military Unit (SMU) deployed in Ireland in February 1992 to apprehend a gang of IRA terrorists – the East Tyrone brigade of the Provisional IRA (PIRA). The Tyrone PIRA had procured a socking great Russian machine gun and planned to use it to attack a police station. The SAS got their men and retrieved the gun, and as a reward they’ve been subjected to decades of interrogation and now an inquest into the deaths of the terrorists shot during the operation.

When Wood wrote his piece, Justice Michael Humphreys, presiding over the inquest, had not yet reached a verdict or released his report. Well, now he has. He has decided that the use of lethal force was not justified and referred the case to the Director of Public Prosecutions.

I spent the weekend reading Justice Humphreys’s report, expecting to find at least some evidence of SAS wrongdoing – some reason to put the soldiers through so many gruelling years of investigation. But what I found is much weirder than that. The SAS unit seems to me to have behaved bravely in tricky circumstances, and certainly just as it had been trained to do. What’s bizarre is the picture painted by Mr Justice Humphreys of how he thinks the SAS should have behaved. It’s a glimpse into life lived by the light of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), and it’s both scary and surreal.

All accounts agree that the moon was full and bright in County Tyrone on the night of 16 February 1992, which was not great for soldiers lying low. The intelligence had been that the PIRA would meet at St Patrick’s in Clonoe before the attack, and the original plan was to apprehend them there, so the men of the SMU hunkered down behind a patchy hedge to wait. Even Justice Humphreys agrees that the hedge provided inadequate cover. But the PIRA didn’t stop by St Patrick’s Church. They drove their gun straight to the Royal Ulster Constabulary station and shot it up with 60 rounds of armour-piercing bullets. Only after that did they drive to St Patrick’s, whooping and shooting, intending to dismantle the gun and escape with the other members of their brigade, 20 IRA in all.

The picture painted is a glimpse into life lived by the light of the ECHR and it’s both scary and surreal

When the truck arrived at St Patrick’s Church, the SMU was waiting. But as the headlights swept towards him, the soldier in charge of the unit – Soldier A, the inquest calls him – judged it likely, given the scrappy cover, that he and his men would be spotted. He describes seeing PIRA members in the back of the truck, one of whom was holding a rifle in the air. So Soldier A opened fire. His men engaged and four IRA men wound up dead.

Article 2 of the ECHR states that everyone has a right to life and cannot be intentionally killed. The ‘Yellow Card’ instructions for opening fire in Northern Ireland insist that a ‘challenge’ must be given before opening fire, but also that a soldier may disregard this if he has reason to believe that announcing his presence to make an arrest would endanger his life, or the life of his men. Hard as I try, I can’t think of a more certain way for a soldier to endanger the lives of his men than by cheerily announcing their presence to 20 IRA terrorists with a burning hatred of the British Army and a heavy machine gun. What choice did Soldier A have?

But here’s how Justice Humphreys thinks things should have played out. In his summary of the events of 16 February, he’s remarkably breezy about the PIRA attack: ‘Some 60 rounds were fired but no one was injured’ – as if it was a naughty jaunt, no harm done.

What the soldiers should have done, insists Humphreys, is to calmly wait in their inadequate hiding place in the bright moonlight for the moment at which the PIRA boys began to unbolt their machine gun from the tailgate of the truck. Then, with every man occupied, it would have been a cinch to saunter up and lawfully arrest the lot of them, in accordance with Yellow Card protocol, no violation of the ECHR.

I long to see inside Justice Humphreys’s mind, the picture he has of this perfect and compliant operation: all 20 IRA men caught unawares and unable to shoot because their hands are full of spanners. Perhaps it stars himself as a sort of Justice James Bond. ‘Rats!’ the PIRA ringleader, Kevin Barry O’Donnell, might say, ‘you’ve outsmarted us with your spanner trick.’

Kevin Barry O’Donnell had, by the by, been acquitted a few years previously of bombing an army barracks. ‘I come from a devout Catholic family and do not support the taking of life,’ he said in court.

But the lesson of the Clonoe inquest, and the miserable decision to refer the case for possible prosecution, isn’t just that Justice Humphreys is delusional. It’s that attempts to ensure that military operations, especially Special Forces operations, comply with ECHR law often leads to terrible injustice and punishes the very people we rely on most. No one who didn’t secretly have it in for our country could think otherwise.

I only know three young people who’ve chosen to join the armed forces in recent years and they’re three of the brightest and most moral twentysomethings I’ve met. The idea that, for acting in our country interests, they might one day be hounded through the courts fills me with despair.

Watch more on Spectator TV:

Quite a problem

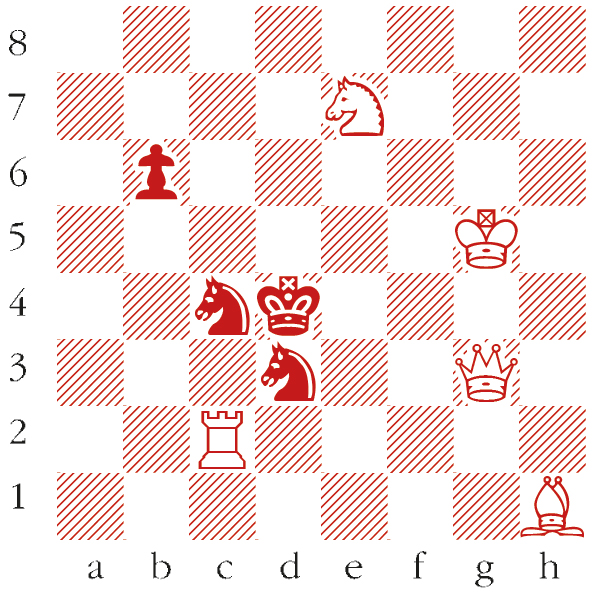

Forty minutes, two problems to solve. Earlier this month I was seated in an examination hall at Harrow school in London, taking part in the final of the Winton British Chess Solving Championship. This was the second solving challenge of the day: two ‘mate in 3’ problems. The first (see the puzzle below) was a beauty and I was delighted to crack it within ten minutes. So far so good, and I had half an hour left to tackle the second.

That’s where I got stuck. For one thing, the irrational position (see diagram below) made me dizzy. Composed by Aleksandr Feoktistov in 1969, the task is for White to play and give mate in three moves or fewer. Black’s king is immobilised in the centre, and there are countless ways to threaten mate on the next move, but three moves is a tough constraint to meet, given the range of defensive resources. For example, 1 Nxg4 threatens mate with Ng4-e3, and then 1…Rxg4 2 Qxg4 N1e2 (to prevent Qg4-d4#) 3 Rd6+ Kc5 4 Rbc6 mate is four moves – that’s one too many.

When solving a chess problem, for every eureka moment there are a dozen dead ends. I tried unsubtle moves, like 1 Qf6, (to threaten Qf6-e5 mate), but the king just legs it: 1…Ke4. In composed problems an inspired ‘waiting move’ can be a valid approach, so I looked at mysterious moves, like 1 Qc2 or 1 Bh8, hoping the secret would soon reveal itself. Those went on the scrapheap too: in each case 1…Rc4 is one of several adequate replies. Back to the crude stuff: 1 Nxg3 (to threaten Qg6-g5+ and mate next move), but there is no mate after 1…Ne4. The slippery king eluded all my attempts at capture.

Another of my primitive ideas was 1 Nxg8, to threaten Ng8-e7 mate, but Black can play 1…e5, creating an escape square on d4. The correct answer is an elegant refinement of that: 1 Rc7! threatens 2 Nxg8 followed by 3 Ng8-e7 mate, whereupon …e6-e5 can be met by Rb6-d6 mate. Black has various defensive tries, but they all fall short, e.g:

– 1…Rc4 2 Rd7+ Kc5 3 Bf8#

– 1…Rd4 2 Nf6+ Ke5 3 Qg5#

– 1…Re4 2 Qg5+ e5 3 Qd8#

– 1…Nd1 2 Rxb5+ Kd6 3 Be5#

– 1…Nd3 2 Qxd3+ Rd4 3 Qxd4#.

– 1…Bf7 2 Nxf7 followed by 3 Qxe6# or 3 Rd6#

In a chess-solving contest, the marking is merciless, and there are no points for finding wrong moves. For the most part, you either find the right idea or you don’t. Half an hour of spinning my wheels produced a catalogue of duff ideas. Nul points.

Even by the standards of a solving competition, this problem was unusually difficult, and only two solvers received full marks for it. One was Eddy Van Beers, a grandmaster of competitive solving from Belgium, who achieved the highest overall score from the six rounds that day. (The event welcomed participants from overseas, though they were not eligible to win the British title.) The other was David Hodge, the reigning British Solving Champion, who repeated his success to earn his fourth British title. He finished ahead of Jonathan Mestel – also a many-time British Solving Champion, as well as a grandmaster of over-the-board chess. I was happy to finish in third place among the Brits.

No. 839

White to play and mate in two moves. The original problem was a mate in three, composed by Godfrey Heathcote for British Chess Magazine in 1904. In this, the most beautiful variation, White has just two moves left to give mate. What is the first move? Email answers to chess@spectator.co.uk by Monday 3 March. There is a prize of a £20 John Lewis voucher for the first correct answer out of a hat. Please include a postal address and allow six weeks for prize delivery.

Last week’s solution 1 Rxb7+! Rxb7 (or 1…Ka8 2 Rxb6 wins easily) 2 Qxa6+ Kb8 3 Qxb7 mate.

Last week’s winner Andrew English, Abingdon

Spectator Competition: Stockpiling

For Competition 3388 you were invited to submit a poem written from the point of view of a prepper.

While the topic of this challenge was a bit of a downer, the standard of your poems – inventive, sad and funny – was cheering. I was sorry not to be able to fit in Chris O’Carroll’s nod to the Beatles: ‘We’re the Ardent Preppers’ Chance Stockpile Band…’ and David Silverman’s twist on Masefield’s Cargoes:

Wrinkle-cream of Nivea on discount offer:

Packed, for life on sunny Exoplanet 59,

With box sets of Homeland,

Line of Duty,

Game of Thrones and Last of the Summer Wine.

There were near-misses, too, for Bill Greenwell and Nicholas Hodgson, but the £25 John Lewis vouchers go to those below.

When comes war and devastation (as foretold in Revelation)

Then most will weep and groan, but I’m no mug

When the bombs fall helter-skelter

I’ll be grinning in my shelter

Snug and smug

While the likes of you are dying, it’ll be so satisfying

To know that I’m surviving everyone.

Nuclear aftermath is viable

If you’ve stockpiles and a Bible

And a gun.

So I’m ready dressed in camo, lightly fingering my ammo

Prepared for all the carnage and the woe.

Midst the ruins and the looting,

I’ll be there and I’ll be shooting.

Way to go!

George Simmers

’Twill come when it will come was Shakespeare’s line,

though he meant Death not some apocalypse,

springing from Fate or rogue AI’s design,

or human error if a finger slips.

Best be prepared with water, tins of beans,

tin-opener (plus some spares), Swiss Army knife,

vitamin tablets, caseloads of sardines,

the bare necessities sustaining life.

But we are more than beasts. I’ll take my cue

from Desert Island Discs: Shakespeare, of course,

and Bible, then not too much Temps Perdu

but every Jeeves and Wooster for the sauce

of laughter, Archy and Mehitabel

(those true philosophers), and Ulysses,

its end something to aim for, before Hell

or lack of crosswords brings me to my knees.

D.A. Prince

I am the very model of a modern day survivalist,

My bunker’s so desirable I’ve had to start a waiting list,

Its freezer’s full of bagels by a Bake Off semi-finalist,

And if it needs defending I’m an automatic-rifleist;

I purify the water using iodine and filter kits,

I’ve got a well-stocked cellar if instead I want some gin-and-its,

I’ve piled up so much booze it takes all day if I recite a list –

I might spend Armageddon getting very gently Brahms & Liszt;

I monitor the frequencies to check if there are aliens,

I bought a load of jammers from some special ops Ukrainians,

I’ve infrared defences which will perforate noctambulists,

And landmines which are guaranteed to marmalise detectorists;

My seed-bank’s full of veggies and some ancient strains of barley too –

I’ve got a DuoLingo app in case I need to parlez-voo –

I’m practical and focused – I’m a prepper, not a fantasist:

I am the very model of a modern day survivalist.

Tom Adam

Gonna hunker in me bunker

Wi’ me water, tins’n’guns

And me gasmasks – I’m no funker –

For when Armageddon comes

And a Chinese or a Russkie

Blows the world to smithereens,

I’ll be ’ere to tell ’em gruffly

What Survivalism means.

Gonna swelter in me shelter

Waitin’ on that bitter End,

Arms’n’groceries? I’ve a welter

’Ere arrayed for me to spend

As, outside, nucular winter

Keeps their prices surgin’ up.

I’ll be last, in this land hinter,

With a runnin’ over cup.

Adrian Fry

On Monday I bought a prep bunker –

The size of it made us all cheer,

I filled it with pasta, tinned veggies and rice –

Plus med kits, for end times are near.

And that bunker, it made me so thankful,

Its power supply, off-grid loo,

Some weapons. Huge batteries. A stash of dried soups.

We’ll learn to survive. We’ll make do.

We’ll batten down with hoarded foodstuffs,

Do workouts, store water, and weave,

While outside the world falls to civil unrest,

So poorly equipped, so naive.

Bring on the apocalypse fallout,

I’ve seed banks and games on my list,

And we’ll sail through doomsday in comfort,

I love it. At least we’ll exist.

Janine Beacham

No. 3391: Ode-worthy

You are invited to submit one of Keats’s odes rewritten as a sonnet or a limerick. Please email entries to competition@spectator.co.uk by midday on 12 March.

2692: Flexibility

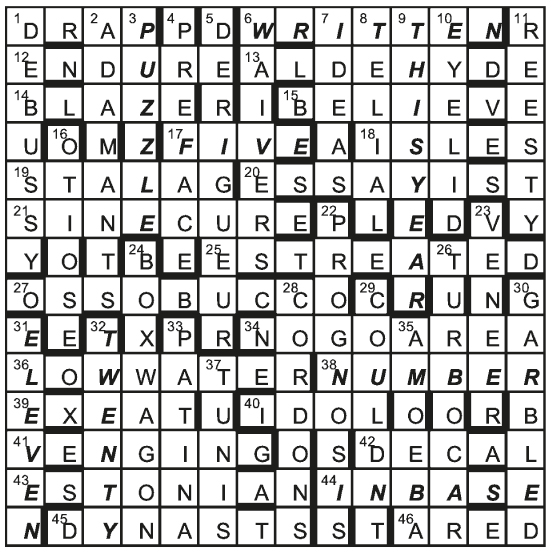

We welcome the duo called Madrigal to the compiling team this week. The unclued lights (including four of two words) can be arranged to provide a quotation (in ODQ) and its author.

Across

10 Learn of American through grammar school covers (6,4)

12 African country’s note covering one rule (6)

13 First-rate head polled children (3-5)

16 Song featured in Top of the Pops, almost every week (5)

17 Instrument Luke played on the railway with energy (7)

18 Newcomer, one that yearns in Scotland? (7)

20 Pure wits dismantled reviews (5-3)

26 Impress English with praise (7)

28 Distribute evenly in New York for speed (7)

31 Cabalist crumbled like rock (8)

34 Young boys are pickpockets (7)

36 Nothing souses drunk like a Costa? (7)

39 Close, perhaps, reporting depression (5)

40 Working a lever to lift (8)

41 Average out as in French summer (6)

42 Priests, perhaps, redeveloping Bern Castle (10)

43 Hardy fish in enclosure (6)

44 Northern calypso dancing cause of fainting fit (8)

Down

1 Titipu’s heroine anticipating a delicious meal? (3-3)

2 Male’s ire turns more petty (8)

3 Question European protection (6)

4 Strap in with ongoing cover (5)

6 Sisters displaying one in new style (4)

7 ‘Nothing to clear up in post’ is showing off (11)

8 Scottish stranger involved in gun control (4)

14 Briefly analyse standards (4)

16 Do pie recipe cooking from historical novel (6,5)

19 Expressing hesitation to depart so (4)

21 Fluid waste from ancient city river (4)

22 Indulged animals offended feelings (4)

23 Clear out modern vehicle with a clever limiting of acceleration (8)

24 Dog that has lifetime that is long (7)

27 Head over after liturgy’s slow passage (8)

30 Dubious character giving odds on four (4)

31 British routine that’s not sweet (4)

35 Slow, lazy obnoxious bodies suggested primarily (5)

Download a printable version here.

A first prize of a £30 John Lewis voucher and two runners-up prizes of £20 vouchers for the first correct solutions opened on 17 March. Please scan or photograph entries and email them (including the crossword number in the subject field) to crosswords@spectator.co.uk, or post to: Crossword 2692, The Spectator, 22 Old Queen Street, London SW1H 9HP. Please allow six weeks for prize delivery.

2689: Annus impuratus? – solution

The puzzle title alluded to a ‘base year’ and the message spelt out using unclued lights was ‘PUZZLE NUMBER is THIS YEAR, TWENTY TWENTY-FIVE, when WRITTEN IN BASE ELEVEN’.

First prize R.J. Green, Guildford

Runners-up John and Di Lee, Axminster; Kathleen Durber, Stoke-on-Trent

The weirdness of the pre-Beatles pop world

Quizzed about pop by the teen music magazine Smash Hits in 1987, the year of her third consecutive electoral victory, Margaret Thatcher singled out ‘Telstar’, a chart-topper from a quarter of a century earlier, for special praise. She pronounced it ‘a lovely song… I absolutely loved that. The Tornados, yes.’

As a whizzily futuristic sounding instrumental ode to a transatlantic communications satellite, and only the second British recording to top the American Billboard charts, its charm for Thatcher was perhaps as much political as musical. That it was the work of an independent producer might also have appealed to her love of freewheeling, self-reliant private enterprise. Roger George ‘Joe’ Meek largely eschewed major label studios to record in a makeshift set-up in his flat above a leather goods shop at 304 Holloway Road.

Rather less on message for the espouser of family values, however, was that Meek, in 1963, was fined for ‘importuning for an immoral purpose’ at the public lavatories at Madras Place. This was a notorious ‘cottage’ not far from his home, frequented by gay men seeking casual sex. And just four years later, on 3 February 1967, Meek would murder his landlady, Mrs Violet Shenton, blasting her with a double-barrelled shotgun following a row over the rent book, before turning the weapon on himself.

Darryl W. Bullock, who died in December, profiled Meek in his 2021 book The Velvet Mafia: The Gay Men Who Ran the Swinging Sixties, alongside such contemporaries as Larry Parnes, Robert Stigwood, Joseph Lockwood and Brian Epstein – all of whom reappear here. But this book is the first standalone biography of Meek for more than 30 years. In that time, the producer has been the subject of at least two documentaries, a play and a biopic, and has appeared fictionalised in crime novels by the likes of Jake Arnott and Cathi Unsworth. He has also been lauded as an audio genius, rather than mocked for his gimmicky effects – a weakness for speeding up vocals being a bit of a call sign.

On 3 February 1967, Meek murdered his landlady, blasting her with a shotgun after a row over rent

Bullock dismisses some of the wilder conspiracy theories that have flourished about that grisly day in February. Most of these feature the Kray twins and their supposed attempts to muscle in on managing the Tornados – by then decidedly past it and devoid of any of the original members. We do, however, learn of the eerie coincidence that Phil Spector, the similarly volatile American record producer whom Meek once accused of stealing his ideas, went on to shoot the actor Lana Clarkson on the same day in February in 2003.

Bullock crowns Meek ‘the Wizard of Odd’, and the producer’s substantial output certainly showed a marked interest in the otherworldly and interplanetary, with the Wild West, ancient Egypt and the Anglo-Saxons thrown in for good measure. Seances in graveyards to commune with Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran and Ramses the Great were among Meek’s surefire means of generating hits for Mike Berry and Heinz Burt. The latter was a Southampton supermarket bacon-slicer turned Tornado bassist who was groomed by an infatuated Meek for solo singing success. Meek encouraged him to emphasise his Germanic heritage by bleaching his hair platinum blond. That Burt could barely hold a note, and faced a nightly barrage of tins of baked beans being thrown at him by teddy boys in dance halls across the land, was beside the point. ‘Just Like Eddie’ – penned as a tribute to Cochran by Geoff Goddard with help from the ‘other side’ – would see Burt land in the top five. But it was Burt’s shotgun which subsequently dealt the fatal blow to the whole enterprise.

Bullock’s book emphasises how driven and phenomenally productive Meek was – though the amphetamines he ate like Smarties severely damaged his mental health. Some 67 tea chests full of tape reels were found after his death, the contents of which are only now being released.

Equally apparent is just how weird the pre-Beatles world of pop was. This was a time when the future Fab Four knob-twiddler George Martin was hailed as a musical visionary for signing the pianist Mrs Mills, ‘a 43-year-old east London secretary’, as a rival to the million-selling ‘queen of ragtime key-thumping’, Winifred Atwell. Meek, like many others, would pass on the Beatles. Though he remained friendly with Epstein, it’s clear that he initially struggled to adjust to the new musical landscape. He was reduced to recording sessions with the Pete Best Four, led by the drummer whom Martin, Lennon and McCartney had deemed surplus to requirements; and he scoured his native Gloucestershire and the West Midlands for alternatives to the Merseybeat boom with somewhat mixed results.

Yet the roll call of musicians who clambered up the stairs of 304 Holloway Road to lay down tracks in Meek’s living room, stairwell and even toilet (favoured for its echo), is prestigious. They included Tom Jones, Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page, Deep Purple’s Ritchie Blackmore, Steve Howe of Yes and Charles Hodges of Chas and Dave cockney duo fame. Meek did, however, reject Rod Stewart, apparently telling him: ‘You look fucking awful, you’re ugly, you’re short, you sound terrible – fuck off!’

Decades before Stock Aitken Waterman or Simon Cowell, Meek was making records with soap stars and television personalities, cutting discs with Jenny Moss from Coronation Street and, more successfully, the actor John Leyton. He sang the Meek-produced Goddard composition ‘Johnny Remember Me’ on Harpers West One, a show that attracted 25 million viewers. The record duly went to number one. David Bowie claimed never to have met Meek, though two groups he played with, the Konrads and the Riot Squad, certainly did. Yet Bowie’s first chart hit, ‘Space Oddity’, bore all the hallmarks of a Meek production circa ‘Telstar’. And Thatcher was right: ‘Telstar’ is a lovely song.

Is Keir Starmer really Morgan McSweeney’s puppet?

Every government has its éminence grise. The quiet, ruthless man (or occasional woman) operates in the shadows, only to be eventually outed when the boys and girls in the backroom fall out among themselves or when someone pens a memoir. Think Peter Mandelson, Nick Timothy, Fiona Hill and Dominic Cummings.

The authors of Get In, both lobby journalists, have produced a detailed insider account of the rise of Keir Starmer, as seen through the eyes of those inhabitants of the political underworld whose names rarely surface in the public prints. In this case, the focus is on one alleged strategic genius, a man in his late forties with the memorable name of Morgan McSweeney, referred to throughout by the somewhat sinister moniker of ‘the Irishman’. These days the Irishman is the head of the prime minister’s office and can be seen marching up Downing Street on his way to work. He was not always so visible.

McSweeney, who spent several months working on an Israeli kibbutz, cut his teeth in the byzantine politics of the London borough of Lambeth, then under the rule of Red Ted Knight, and later in Dagenham at a time when the British National Party was on the rise. In each case he concluded that Labour was losing touch with its natural electorate and resolved to do something about it. To this end, he founded an organisation called Labour Together. Despite its anodyne name, it was, say the authors, ‘a conspiracy… Even the name was a lie. Its mission was division.’

Funded partly by the Jewish businessman and pro-Israel lobbyist Sir Trevor Chinn, it first set about destroying the influential online Corbyn fanzine theCanary by persuading advertisers to withdraw. It also fanned the flames of Labour’s alleged anti-Semitism, feeding grossly exaggerated claims to a compliant media. It was duly rewarded with stories such as a lead in the Sunday Times headlined ‘Inside Corbyn’s Hate Factory’. This succeeded all too well. An opinion poll found that the majority of the public was under the impression that 34 per cent of Labour’s 500,000 members faced accusations of anti-Semitism, whereas the real figure was 0.3 per cent – and many of those were unproven.

The authors make some large claims. They credit McSweeney and his friends with persuading Starmer to run for the leadership after Corbyn’s resignation, and then organising his successful campaign. I doubt whether Starmer took much persuading to run. He was obvious leadership material from the moment he entered parliament. Nor did one have to be a strategic genius to foresee his election as leader. Having lost four elections in succession, there were many Labour members of all persuasions who saw Starmer as easily the most credible candidate. Even so, some deft footwork and a high degree of cynicism were required to render him acceptable to the overwhelmingly pro-Corbyn party membership. McSweeney and his associates can certainly take credit for that.

Once Starmer became leader it was a different story:

Having declared himself a friend of Corbyn’s and promising unity, he proceeded to purge the Labour party with unprecedented vigour. Every principle he said he held dear in 2020 has been ritually disavowed.

Corbyn himself, falsely smeared as some sort of racist, was successively suspended from party membership, reinstated but excluded from the parliamentary party, and suspended again before heading off into the political wilderness. A small clique on the Labour national executive also set to work trawling social media in search of dissidents to expel (a number of whom were pro-Palestinian Jews) and purging the list of parliamentary candidates.

These days McSweeney can be seen marching up Downing Street to work. He was not always so visible

Given the mess the Tories were in, it is quite a large claim to suggest, as the authors do, that McSweeney and his associates had much more than a minor impact on the remarkable outcome of the 2024 election. They played a part, to be sure; but the size of the majority was almost entirely due to a quirk of the first-past-the-post electoral system and the fact that for the first time in living memory the Tories had to compete for votes with a credible party to their right. To win almost three times as many seats as the Tories on just 34 per cent of the popular vote suggests that Labour stands on a very narrow beachhead.

Starmer does not come out well from this book. He is variously portrayed as a pawn in the hands of clever manipulators, an HR manager, a passenger on a train driven by others. Like him or loathe him, there is a great deal more to him than that. The authors are so obsessed with process that they sometimes miss the big picture.

The most glaring omission is a proper discussion of the thinking behind what was arguably the biggest blunder of the pre-election period and one that may haunt this government to the end. In the year before the election, the chancellor Jeremy Hunt slashed national insurance contributions by one third, at huge cost to the exchequer. It was a trap into which Labour fell headlong. Instead of denouncing this as a cynical, irresponsible gimmick and fighting the election on the dire state of the public sector, Starmer and Rachel Reeves pledged not to reinstate Hunt’s cuts. As a result, they have had to resort to some very unpopular measures to try to make up the shortfall. The pit is deep and it may get deeper yet.

One wonders, too, why none of the young master strategists portrayed in this book saw fit to advise their employers that it probably wasn’t a good idea to accept freebies from the multi-millionaire donor Wahid Alli. Not that they should have needed telling.

Heaven knows where all this will lead. As a former senior member of the Blair government remarked to me the other day: ‘Four years from now Nigel Farage could well be prime minister.’

The world is now inexorably divided – and the West must fight to survive

In The Builder’s Stone, Melanie Phillips reminds us forcefully that we must never forget how 7 October 2023 changed the world. On that day Hamas terrorists from Gaza invaded southern Israel and brutally raped women and butchered or burned alive 1,100 Jewish men, women and children. They also dragged 250 Israelis, including three-year-old twins, grandparents and young women whom they had already attacked, into Gaza as hostages. They filmed it all on their body cameras, and perhaps the most terrifying thing they recorded was the glee with which they carried out these atrocities.

Phillips, a British writer who lives in Jerusalem and London, has spent many decades fighting Goliaths. Like David, she has fired well-aimed stones at left-wing educationalists, enemies of traditional families and others determined to remake the world according to what she deems destructive progressive agendas. In this fearless and invaluable book she describes the horror she felt that after the worst slaughter of Jews since the Holocaust, the West did not immediately rally to Israel. Instead:

A tsunami of brazen, frenzied Israel-hatred and anti-Semitism erupted across the West. Ever since the pogrom, western capitals (and especially campuses) have been besieged week after week by thousands of Muslims, the hard left and Palestinian supporters, who have chanted for the destruction of Israel, jihadi holy war and the murder of Jews everywhere.

Phillips is right. I never imagined that we would see demonstrators in London screaming: ‘Death to the Jews.’

It recently emerged that even as the torture of Israelis was taking place on 7 October, pro-Palestinian groups in London were informing the police that they were organising a protest against Israel for the following Saturday. No wonder that friends in Britain’s tiny but essential Jewish community are frightened for their children and for the first time ever considering leaving the country.

All this crystallised Phillips’s fears about the decline of western civilisation – also known as Judeo-Christian civilisation. Her book’s title references a verse in Psalm 118: ‘The stone that the builders rejected has become the cornerstone.’ She argues that for the West to survive it must once again base itself on the Jewish and Christian values that gave it strength and goodness. And remember, Judaism came first:

The moral principles assumed to have been invented by Christianity, such as compassion, fairness, looking after the poor or putting others first, were all introduced to the world by the Hebrew Bible… Judaism is the foundation stone of western civilisation.

But, she goes on to argue, the West has been tragically weakened since 1945 because it has stopped believing in itself. ‘To be more precise, political and cultural leaders have stopped believing in the West.’ The demoralisation began with the Holocaust, which took place at the epicentre of western high culture. This horrific failure encouraged many post-war left-wing intellectuals to blame ‘the entire Enlightenment project, and reason itself, for the rise of fascism’. Under such corrosive ‘progressive’ influences in the past half century, the western world has witnessed the deconstruction of the family and education, the erosion of religion and demographic decline.

The dreadful events of the past 16 months show that the world is now inexorably divided, she says. One side wants to preserve core values, such as national identity and cultural self-belief; the other seeks to replace the traditions and principles of the West with ‘a brand new world of deracinated individuals dedicated to breaking the bonds of attachment between successive generations and their nation’s inherited culture’.

She also argues that this cultural crisis is being exploited by the growing number of Islamist extremists in Europe and the US, who make the most of our increasing weakness. She believes that we must be resilient, above all, and learn from the Jewish people’s extraordinary culture of survival. She quotes Napoleon: ‘Any nation that still cries after 1,500 years is guaranteed to return.’ Faith is as crucial as courage to the survival of the Jews. Phillips describes how Jewish prisoners in Auschwitz secretly used the camp’s kitchens in the middle of the night to bake matzo (unleavened bread) for Passover, risking instant execution. The West, she says, must be equally fearless, and must renew faith in itself if it is to survive.

Churchill declared that ‘war is mainly a catalogue of blunders’, and Israel has made its share of those since 7 October. But, says Phillips, quite correctly: ‘Israel is demonised for defending itself as effectively as possible against an enemy determined to wipe out the Jewish state and kill every Jew.’ Hamas is a viciously racist enemy which has deliberately used Gaza’s civilians as shields in its battle against the IDF. Why? Because, as its late leader Yahya Synwar declared, the more Palestinians who died, the more Israel would be condemned. The odious evil of Hamas has been agonisingly demonstrated in their treatment of the Bibas hostage family. The murder of two little boys and the unexplained failure to return the body of their mother have caused national grief and anger in Israel.

A final note from history. In January, on the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, the Jewish Chronicle published moving photos of Jewish women as they were freed from the death camp in January 1945. The same week, Israeli women hostages in Gaza were photographed surrounded by terrifying crowds of masked Hamas gunmen. For Jews, the threats never change. The big difference, which Phillips displays admirably, is that in 1945 the Nazi Jew-killers were defeated. Today, the Islamist Jew-killers are rampant. The West needs to trust in its roots to defeat these new Nazis.

How can a biography of Woody Allen be so unbearably dull?

How do you make the life of Woody Allen unbearably dull? Mainly by retelling the plots of every one of his movies, along with lists of cast and crew, box-office receipts and critical reactions. And there are so many movies – 50 so far, but there’ll probably be another by the time you read this. Long ago, Allen got into the habit of making a film a year, and so he goes on. He once said he was ‘like an institutionalised person who basket-weaves’ – he couldn’t stop.

So we have to wade through an awful lot of filmography before the juicy stuff – the scandal – begins. Mia Farrow doesn’t even appear until page 313. In 1979, when she first met Woody, she was divorced from Frank Sinatra and André Previn and had recently adopted her seventh child. Woody took her out to dinner and thought she couldn’t have been ‘nicer, sweeter’, though he said in his autobiography years later that he should have been ‘more alert’ to the fact that her family was ‘rife with extremely ominous behaviour’. (Her father, the film director John Farrow, was an alcoholic and possibly an abuser.)

Anyway, Woody started taking Mia out. One day in the cinema she suddenly said: ‘I want to have your baby.’ But he changed the subject to lawn-mowers, and then promised to have to think about it, which she knew meant talking to his therapist. After they’d dated for six months, Mia decided she wanted to introduce him to her children, and he found them ‘very cute’, though at 45 he had zero interest in children.

Mia wanted to get married, but he didn’t, so they lived in separate apartments facing each other across Central Park. He saw her every day and would take her out to dinner, but he never stayed the night because there were cats, dogs and gerbils running loose in her apartment and her bedroom was ‘strikingly nunlike’, with a crucifix over the bed. Nor did he like her country house, Frog Hollow, because the bathroom shower had a drain in the middle – he had a thing about showers. Still, Mia believed it was a ‘steady, secure and satisfying relationship’. And it seemed a good sign when he swapped his white Rolls-Royce for a stretch limo big enough to take all the kids.

Mia still kept saying she wanted to have his baby, and finally the therapist gave permission to go ahead. But then she didn’t get pregnant (she was almost 40), so she looked for a baby to adopt. She knew it would have to be a blue-eyed, blonde girl to appeal to Woody, and she found one and called her Dylan. Woody was immediately smitten and loved holding the baby and giving her his thumb to suck, but said: ‘I don’t want to be there when the diapers are changed or anything awful happens.’ Then Mia unexpectedly fell pregnant and had baby Satchel (later called Ronan); but Woody took no interest in his own son, ‘the completely superfluous little bastard’, and remained fixated on Dylan.

Woody wanted to adopt Dylan, but was told he couldn’t because he was not married. Mia was secretly relieved. Meanwhile, he was getting to know her other children, especially the adopted Soon-Yi, who shared his passion for watching sports. Allen took her to New York Knicks games and to screenings when she was 19, and kissed her while they were watching The Seventh Seal. Soon they were in bed together and he was taking Polaroids of her naked. He put most of them in a drawer, but left some on the mantelpiece where, inevitably, Mia found them and went berserk. She rang all her friends saying Woody had ‘raped her retarded daughter’ – she always maintained Soon-Yi was retarded, though no one else thought so. She became increasingly convinced that Woody had molested Dylan, and put a sign on the Frog Hollow bathroom door that read: ‘Child Molester at Birthday Party! Molded then Abused One Sister. Now Focused on Youngest Sister. Family Disgusted.’

Woody took no interest in his son, ‘the completely superfluous little bastard’, and remained fixated on Dylan

Mia wanted to stop Woody seeing any of the children, but he successfully fought for visitation rights and fixed a custody visit for 4 August 1992. Mia went out, but told the children to watch him like a hawk. They reported that he and Dylan had disappeared to a crawl space in the attic for 20 minutes, and Mia noticed that Dylan was not wearing knickers. Next day, she asked Dylan what happened and filmed her answer: ‘He touched my privates’; and ‘It hurt when he pushed his finger in.’ Mia rang her lawyer, who told her she had to report it to the police. Woody then launched a lawsuit claiming that Mia was ‘emotionally disturbed’ and had falsely accused him of abusing Dylan and Satchel. The news immediately swept round the world.

The press were soon on to his affair with Soon-Yi, and he put out a statement: ‘Regarding my love for Soon-Yi, it’s real and happily true.’ He said that taking nude photos of her was ‘a lark of the moment’. She was by then a college student and they were dating. Soon-Yi gave interviews saying of Mia: ‘I don’t think you can raise 11 children with sufficient love and care. Some of us got neglected, some got smothered.’

Although Woody was never charged, and has always denied the sex abuse allegations, they have hovered over him ever since. Many people said they could never again watch a Woody Allen film, and actors (except Diane Keaton) said they regretted ever working for him. In 1997 he married Soon-Yi, then 27, in Venice, and they adopted two girls. He also stopped having therapy after 30 years and said it had not been as helpful as he hoped – though when he first met Mia she said he couldn’t even buy sheets without consulting his therapist.

Mia and Ronan (formerly Satchel) have kept up the war against Woody which was later joined by the #MeToo movement. Dylan continued to say that Woody had abused her. But Mia’s son Moses, who had denounced Woody at the time, later said that the Soon-Yi relationship was ‘not nearly as devastating to our family as my mother’s insistence on making this betrayal the centre of all our lives from then on’. He added: ‘Life under my mother’s roof was impossible if you didn’t do exactly as you were told.’

Woody is now 89 and still churning out a film a year. He is in good health, apart from deafness, and remains happily married to Soon-Yi. Patrick McGilligan has written countless film biographies, so it is reasonable to ask, as he does in his acknowledgements: ‘Why Woody Allen, and especially why now?’ Perhaps, like basket-weaving, he just can’t stop. There are plenty of biographies of Woody Allen. This must be one of the dullest.

BMW’s Oxford retreat signals deep trouble for UK carmaking

Among British car factories, Nissan at Sunderland is the most productive and Jaguar Land Rover at Solihull probably the most advanced. As for industrial landmarks, the former British Leyland complex at Longbridge is reduced to a research and development facility for Chinese-owned MG; but ‘Plant Oxford’ at Cowley, the original home of Morris Motors now owned by BMW of Germany, still produces 1,000 Minis per day. And BMW’s decision to halt a £600 million project to build electric Minis there is, I fear, a moment of destiny for the whole UK auto industry.

The truth is that the transition to electric cars has descended into chaos. Total UK car production in 2024 was at its lowest (in non-pandemic conditions) since 1954. EVs are too expensive; charging infrastructure is too patchy; manufacturers plead that the current ‘zero-emission vehicle mandate’ (ZEV: 80 per cent of new cars must be electric by 2030, all by 2035) is too tight – though Ed Miliband would like it tighter.

Results are awaited from an industry consultation on how to make the ZEV more workable. But one thing’s for sure: ministerial diktat won’t shift consumer choices; non-urban motorists don’t want to drive electric. And British carmaking, for all its engineering prowess, is wholly dependent on investment decisions from Germany, France, India, Japan and the US, whose domestic markets face the same negative trends and advancing low-cost Chinese competition. BMW’s reversal of Plant Oxford’s fortunes is a signal of much deeper trouble ahead.

Under water

Thames Water is another fiasco. The debt-laden privatised utility is about to borrow £3 billion from existing creditors – on very expensive terms that must feed through into higher water bills for 16 million unhappy customers – as a last resort to stave off collapse that would land big losses on investors and most likely lead to temporary renationalisation. All this for what really ought to be a simple business, supplying water at regulated prices sufficient to keep pipes and reservoirs in good condition and provide steady returns for shareholders.

But Thames never recovered from the decade after 2006 when the Australian bank Macquarie loaded it with debt and gouged it for dividends. Now its best hope for remaining in the private sector may be a bid from CK Hutchison, the Hong Kong group that already owns Northumberland Water and is a flagship company of Li Ka-shing, Asia’s richest and shrewdest conglomerate builder. Li himself is 96, but if his people can’t sort out Thames Water, I doubt anyone can.

Save the cash Isa

Is the Chancellor seriously considering scrapping or restricting cash Isas, the tax-free savings device that attracted a record £50 billion last year? This surge was partly a response to falling interest rates and partly a reflection of UK savers’ customary lack of enthusiasm for riskier investments, including equity Isas. BlackRock, Fidelity, Abrdn and other top fund managers met Rachel Reeves last week, reportedly to discuss ditching the cash Isa in order to divert more capital into the lacklustre market for London-listed equities.

But the idea of an additional UK equity Isa allowance has already fallen away because the sector did not think the product would appeal to customers – so why would cutting tax breaks on cash drive them in that direction? Cash Isas may be a low-margin nuisance for global fund managers, but they were introduced by Gordon Brown long ago to encourage the savings habit, not as a tool for intervening in capital markets.

By scrapping them, Reeves might scoop more revenue from taxable deposits. But if she claims she’s doing it to boost investment-starved high-growth British companies, she’s misguided or bluffing. Meanwhile, don’t forget to take up your £20,000 annual Isa allowance before the end of the tax year. There are four main categories, one of them is cash, and the choice is still yours.

Vote Bogtrotter

I popped into the Cambridge Theatre – at last, having lived next door for four years – to see Matilda the Musical. It’s a terrific show, but does it offer parables for this column? A used-car scam perpetrated by Matilda’s father has echoes of the current car finance scandal – and is brought to order far more effectively by comic Bulgarian gangsters than it might have been by the real-life Financial Conduct Authority.

As to politics, the horrible headmistress Miss Trunchbull instantly recalled Donald Trump but I fear goody-goody Matilda herself may grow up to be a Kamala Harris. For me the brightest hope was Bruce Bogtrotter, the plump kid (played by Adam Hussain) whom Trunchbull forces to eat a huge chocolate cake. When he launched the finale by climbing on his desk to belt out ‘Revolting Children’, I thought: America must find its next-generation President Bogtrotter.

Pedicab menace