-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

From the archives: Rupert Lowe’s first fight for freedom

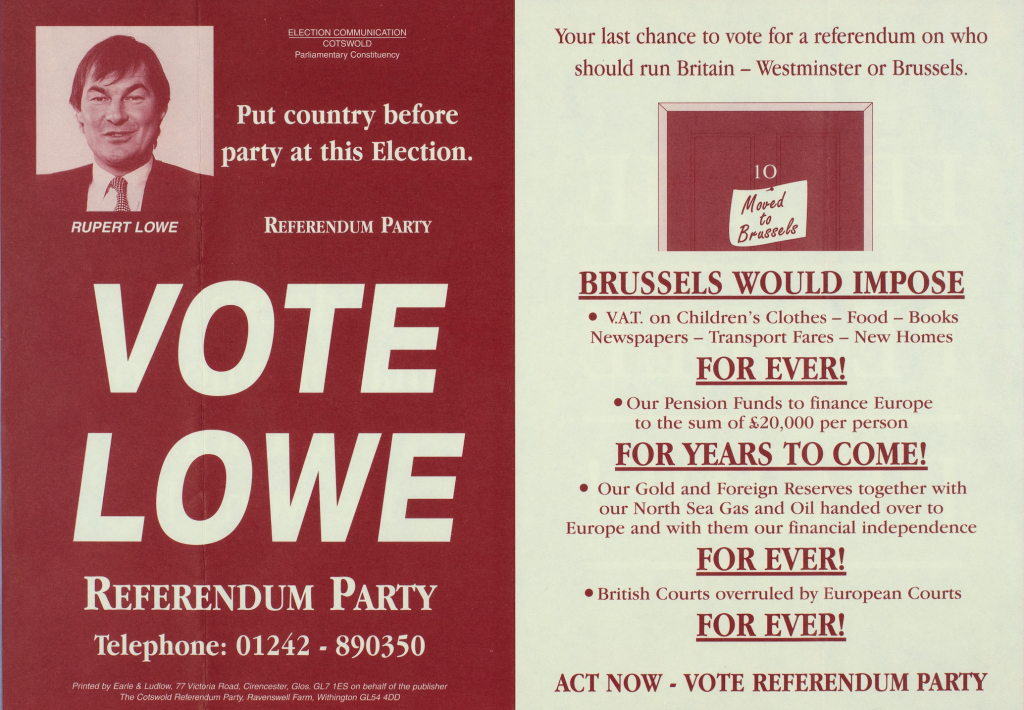

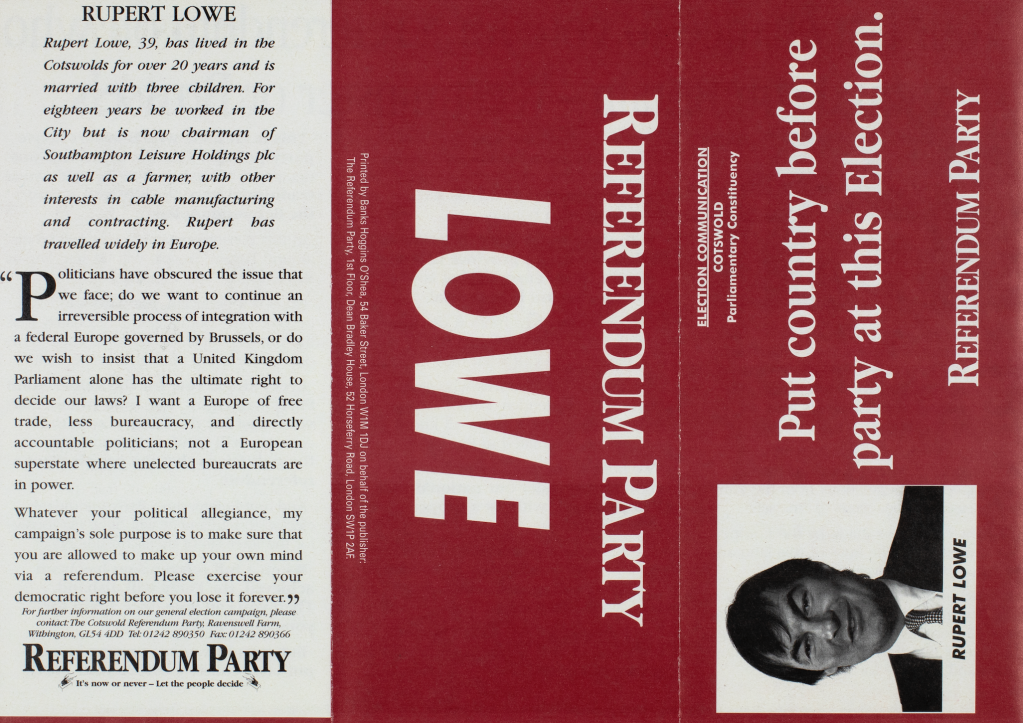

These days, it’s rare to find an MP who is consistent in his politics. So Mr S was delighted to discover on a trip to the archives that there is an exception to this usual rule. Rupert Lowe has served as the no-nonsense Honourable Member for Great Yarmouth since July 2024. Prior to his election as a Reform MP last year, Lowe was an MEP for the brief-lived Brexit party in 2019, which topped the European elections and toppled Theresa May.

But, two decades before that, Farage and Lowe were candidates for rival Eurosceptic parties at the 1997 election: the former for Ukip, the latter for Jimmy Goldsmith’s Referendum party. Steerpike has done some digging and found that some old leaflets of Lowe exist in the Special Collections of Bristol University. They show the Old Radleian has barely changed his politics in 28 years, with images of the-then-39 year old appearing alongside a plea for patriotism and democracy.

‘Put country before party at this election,’ urged Lowe in his address. As a candidate for The Cotswolds, he described himself as someone who ‘has travelled widely in Europe’ with ‘eighteen years’ in the City plus experience in farming, cable manufacturing and contracting. ‘I want a Europe of free trade, less bureaucracy and directly accountable politicians,’ he told voters. Sadly, his plea fell on deaf ears as he only finished fourth with 3,393 votes – enough to keep his deposit.

Luckily for fans, Lowe was undeterred and made it into parliament nearly three decades later.

There is reason behind Trump’s AI Gaza video

Donald Trump really knows how to wind up his political opponents. That has to be the only rational explanation behind his decision to share on social media a video – apparently AI-generated – of what a US-owned Gaza Strip could look like in the future. It is 35 seconds of unadulterated visual idiocy, veering from the bizarre to the senseless. Why do it? What is the point, exactly?

The video starts with the territory in ruins after the war with Israel, with the caption ‘Gaza 2025… What’s next?’ The US president is shown sharing a cocktail, topless and poolside, with the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu. These are not flattering shots by any stretch of the imagination. The video features plenty of Elon Musk, the tech billionaire charged with rooting out government inefficiencies, and an ever-present figure in the Trump entourage. Musk is depicted eating hummus and throwing wads of cash in the air. He looks unconvincingly svelte: AI clearly hasn’t seen Musk in real life. The rebuilt land also features a ‘Trump Gaza’ hotel, and children are seen holding golden balloons adorned with Trump’s face. Also on display is a huge (yes, golden) statue of the American president. It is safe to say that the image does not exactly flatter Trump, who looks distinctly obese.

The video also features a song praising Trump, with the somewhat excruciating lyrics: ‘Donald is coming to set you free, bringing the light for all to see / No more tunnels, no more fear, Trump Gaza is finally here.’ Just as bizarre is the footage of bearded belly dancers. Why are they there? The AI version of Trump is seen boogying with a non-bearded belly dancer. It has not been made clear – so far at least – how, and when, belly dancers became an integral part of Trump’s Gaza reconstruction plans. Did Trump, known for having a short attention span, even watch this video in its entirety?

Others – predictably enough – see in this latest episode signs that Trump is once again eager to display his contempt for established political norms and basic civilities. Doesn’t Trump, demand his detractors, know about the dire humanitarian situation in Gaza? This is almost as batty in its po-faced condescension. Trump is someone who exists on social media. Posting videos is what he does. He did not comment on the video after sharing it. Maybe, just maybe, it’s nothing more than one more social media post made by Trump, soon to be replaced by countless other posts and commentary. People are entitled to expect better of the man occupying the Oval Office but that doesn’t mean Trump has to oblige.

It may just be possible that there is method behind the Trump ‘madness’. Few believe that his plans for Gaza, including the transfer of Palestinians out of the territory, are realistic. His talk of dismantling all the dangerous unexploded bombs and other weapons in Gaza, levelling the place, and turning it into a US-owned ‘riviera of the Middle East’ is just that – all talk. His ideas have been greeted with outright hostility from neighbouring Egypt and Jordan. These countries have no intention of taking in more Palestinians, pointing out that it would merely perpetuate a regional cycle of violence. Britain and other supporters of a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are also strongly opposed.

Yet what Trump has succeeded in doing is making the Arab nations of the Middle East focus afresh on finding workable plans of their own for the future of Gaza. Last weekend, the leaders of seven Arab countries held talks in Saudi Arabia on the way forward. The Arab states are set to unveil further details of their thinking on Gaza at a meeting in the Egyptian capital Cairo early next month. This is the context in which Trump’s online sharing of the Gaza video should be seen. The attention of millions of people worldwide has been engaged by this strange, rather mad computer-generated fantasy vision of a future Gaza. It’s got everyone thinking about the issue afresh. That can’t be all bad.

Britain must learn from the Netherlands’s mistakes on assisted dying

As a former member of a euthanasia review board in the Netherlands, I have closely followed the debate surrounding Kim Leadbeater’s assisted suicide bill. In 2001, and with 15 years of experience with makeshift regulations behind us, the Netherlands became the first country to introduce a euthanasia law. In support of this law, I worked from 2005 to 2014 for the authorities in charge of monitoring euthanasia cases. I was convinced that the Dutch had found the right balance between compassion, respect for human life, and guaranteeing individual freedoms.

However, over the past two and a half decades, I have become increasingly concerned as I have witnessed the steady expansion of the euthanasia system and its eligibility criteria. A system designed to apply to comparatively rare cases was, by 2023, accounting for 5.4 per cent of all deaths in the Netherlands, with the numbers continuing to rise. In one region, euthanasia even accounts for up to one in every six deaths. Euthanasia in the Netherlands is now available to children, and indeed infants, of all ages, and there are continuing attempts to extend it to anyone over 74 who considers their life ‘complete’. In May 2023, a Kingston University study found that there were 39 cases of euthanasia in the country for people with learning disabilities, autism, or both between 2012 and 2021. We have also had our fair share of contested stories, including a well-known case in 2018 involving a woman with dementia being euthanised apparently against her will, as family members insisted that her advance directive should trump her present expressions.

Much about the debate in the UK reminds me of our experience in the Netherlands, including Leadbeater’s insistence that the rules will be strict. Our safeguards were presented that way too. Euthanasia campaigners assured us that it would only apply to a well-defined group of patients. It is through bitter experience, through being on the front-line here in the Netherlands for almost two decades, that I have concluded that it is not possible to regulate and restrict assisted dying safely in the way its advocates claim. Once the first step is taken, euthanasia advocates invoke the principle of equality: why is assisted death only for terminal patients, as chronically ill patients may suffer all the more? Why only for sick physically patients, given the absolute horrors of psychiatric suffering? Why not include people with non-medical causes of suffering, such as grief? And once we allow euthanasia for competent patients, why withhold this blessing from the incompetent?

I know that right now leading campaigners for assisted suicide laws in the UK are asking people to believe that somehow the UK will be the exception, that the safeguards will be unique and enduring. My message to my British friends would be to be incredibly cautious about letting such aspirations triumph over the hard-trodden experience of so many other jurisdictions that have introduced such laws.

The bill is being weakened, not strengthened

I followed some of the parliamentary proceedings late last month where a committee of MPs took evidence from various experts about the bill. I was surprised that all eight of the invited international witnesses are on record as being in favour of assisted dying. The large majority of these experts were Australians, a country not even close to the Netherlands and Belgium in terms of years of experience. Leadbeater should have included witnesses from jurisdictions where assisted dying has been legal for a much longer time, and where things have not worked out as originally promised.

Extraordinarily, every single amendment relating to Clause 1 of the Bill, which aimed to strengthen the proposed safeguards, was rejected. Ahead of second reading, I recall Leadbeater trumpeting her ‘High Court safeguard’, which she said made her legislation the strictest in the world. Leadbeater has now said she is going to drop this safeguard and replace it with panels of experts, likely resulting in them being made up of supporters of assisted dying, as those who do not support the practice would not wish to be involved. The bill is being weakened, not strengthened.

I am also concerned that one MP on the committee has already tried replacing the six-month terminal diagnosis requirement with a 12-month one for certain conditions. Any physician knows how hard it is to make predictions about a six-month life expectancy, and adding a 12-month condition for some illnesses will make the life-expectancy criterion an empty formality. Britain is on a slippery slope. This is exactly what happened in the Benelux countries and in Canada.

How will the Chagos deal be funded?

To the Commons, where Prime Minister’s Questions has this afternoon taken place. Sir Keir Starmer was asked a ranged of questions, from energy to aid to the economy. But while the Labour PM appeared to enjoy his to and fro with Tory leader Kemi Badenoch, on the Chagos Islands he was a little more cagey…

When Conservative MP Kieran Mullan quizzed Starmer on whether the deal to cede sovereignty of the Chagos archipelago would be funded from the Ministry of Defence’s budget, the Prime Minister did not have a straight answer – despite the straightforwardness of Mullan’s question. Pushing the PM, the Tory politician asked:

The Leader of the Opposition gave the Prime Minister an opportunity to unambiguously rule out the funding of any Chagos deal coming from the defence budget and I am not clear that he did that. I want him to be taken seriously in Washington so I will make it really easy for him. Will he rule out the funding of any Chagos deal coming from the defence budget: yes or no?

But despite being asked to offer a straight answer ahead of his meeting with Donald Trump, Sir Keir did not oblige. Responding, the PM remarked: ‘As I said, when the deal is complete I will put it before the House with the costings. The money yesterday was allocated to aid our capability, the single biggest sustained increase in defence spending since the Cold War.’ Er, right.

It comes after the Labour leader told Kemi Badenoch that the extra defence spending announced on Tuesday ‘is for our capability on defence and security in Europe’, with Starmer adding that the money will help Brits ‘put ourselves in a position to rise to a generational challenge’. The question today follows concerns that the UK could end up handing the Chagos Islands back to Mauritius for a billion-pound sum – as well as giving ‘complete sovereignty’ of US naval base isle Diego Garcia to Mauritius.

While the Foreign Office has rejected the suggestion that the deal could end up costing £18 billion, Starmer still hasn’t managed to clear up questions concerning its funding. Stay tuned…

The BBC’s Gaza farce takes another sinister turn

So the moral rot at the BBC appears to run even deeper than we thought. The storm over its Gaza documentary just got a whole lot worse. As if it wasn’t bad enough that this Israel-mauling hour of TV was fronted by the son of a leading member of Hamas, now we discover that the Beeb whitewashed the bigoted views of some of the doc’s participants. It omitted their Jew-bashing. This is as serious a breach of broadcasting ethics as I can remember.

The film was swiftly mired in scandal

Gaza: How To Survive a War Zone was first broadcast on BBC Two last week. The film was swiftly mired in scandal when it was revealed that its 14-year-old narrator is the son of a prominent figure in the Hamas government in Gaza. Yes, our public broadcaster, which we are compelled by law to fund, broadcast an hour-long moan about Israel featuring a kid whose dad has links to the movement that butchered Israel’s men, women and children. Even for the Beeb, it was a new low.

It turns out they went even lower. On at least five occasions in the doc, they mistranslated the Arabic words for ‘Jew’ and ‘Jews’, changing them to ‘Israel’ or ‘Israeli forces’. So when a Gazan woman raged against ‘Yahudy’ – ‘the Jews’ – for invading our lands, someone tweaked it. The BBC subtitles had her saying ‘the Israeli army’ invaded our lands. But that isn’t what she said. She said ‘the Jews’. Is it now BBC policy to conceal hostility towards Jews?

Camera, the Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting and Analysis, has re-translated the documentary, and its findings are chilling. In one scene, the BBC’s subtitles show a boy saying he fled his home because ‘the Israelis destroyed everything, and so did Hamas’. But what he really said was that ‘the Jews came, they destroyed us, Hamas and the Jews’.

A woman is shown saying that Hamas’s 7 October attack was ‘the first time we invaded Israel’ – but what she actually said was: ‘We were invading the Jews for the first time’.

In the most egregious mistranslation, the documentary shows a woman commenting on Israel’s killing of Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar in October last year. Sinwar was ‘fighting and resisting Israeli forces’, her subtitles say. But that isn’t what she said, which was: ‘He was engaging in resistance and jihad against the Jews’.

So our national broadcaster withheld the truth from us. The BBC, which loves to puff itself up as a liferaft of truth in a sea of misinformation, engaged in what was essentially a cover-up, a slippery form of censorship. The filmmakers encountered Gazan after Gazan who slammed ‘the Jews’ for their allegedly wicked behaviour, but the Beeb airbrushed it all away. The people of Gaza are mad at Israel, its doc said, but now we know the truth: some of them are mad at the Jews.

There are so many breaches of journalistic standards here – and of basic morality – that it is hard to know where to begin. Mistranslating the words of foreign interviewees is a huge no-no in journalism. It deceives viewers, blinding us to the truth of how other people think.

As for turning invective about ‘the Jews’ into criticism of ‘Israeli forces’: that isn’t journalism, it’s propaganda. The job of the journalist is to reflect back to us the world as it really is, not to feed us half-baked morality tales. The BBC found people in Gaza who were more than happy to rail against ‘the Jews’ and even to praise ‘jihad’ (holy war) against them. Yet it fed us an image of Gaza as brimming with people who just want to make heartfelt political criticisms of ‘Israel’. It was fake news.

Why would the BBC memory-hole Gazans’ fury against ‘Yahudy’? Why did it even disguise a woman’s celebration of holy war against Jews? It seems to me the Beeb sacrificed objectivity at the altar of political narrative. It knows that the kind of people who watch late-night documentaries on BBC Two probably dislike Israel and pity Palestine. And it couldn’t possibly show these viewers the reality on the ground, which is that many Palestinians sympathise with the monsters of Hamas and disdain ‘the Jews’. So it buried the truth in order to prop up the chattering classes’ infantile conviction that Israel is evil and Palestine is pure.

The end result is that it has essentially provided moral cover for Hamas and its supporters. In erasing Gazans’ fury with ‘Yahudy’, in sanitising their support for ‘jihad’ against ‘the Jews’, it obscured the truth of what Israel is up against. This was a propaganda coup for the terror group that carried out the worst assault on the Jewish people since the Holocaust. It is not good enough that the BBC has now removed this dishonest documentary from iPlayer – heads need to roll.

Trump won’t find a minerals bonanza in Ukraine

US President Donald Trump has announced that Ukraine is ready to sign a deal that gives US investors a share in the country’s mineral riches. Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelensky, who two days ago vowed not to sign any deal that his countrymen would be paying for ‘for ten generations’ is due in Washington on Friday to sign a revised accord. The US’s most controversial demand – that Washington keep $500 billion in revenue from exploiting Ukraine’s resources as payback for military aid – has reportedly been removed from the final text.

While the final details of the deal remain undecided, one thing is certain: the scale of Ukraine’s mineral wealth and its actual value on world markets have been spectacularly overstated by both the US and Ukraine.

US diplomats, as well as both Trump and Putin, often speak of Ukraine’s ‘rare earths’ – a list of 17 metal elements used in tiny quantities in electrical circuits. But according to the US Geological Survey, Ukraine has no significant deposits of rare earth metals (REM). And in any case, the entire world market for REMs amounts to just $15 billion a year – much of which is currently controlled by China.

What Ukraine does have are reserves of non-rare minerals such as titanium, lithium, uranium, cobalt, graphite, copper and nickel – plus gas and coal. The problem is that currently most of these deposits are being exploited only on a tiny scale or not at all, and nor does Ukraine have the capacity for refining most of its minerals into finished products. Ukraine, for instance, exported just $29 million of raw uranium ore in total in 2023 and a mere $11.6 million of titanium ore but none of the much more valuable and exportable titanium sponge. Ukraine also reportedly has half a billion tons of lithium ore – but currently has no lithium mines. Investors will have to pour billions into sinking mines and creating processing infrastructure.

There’s another problem. The world is already oversupplied with many of the minerals in which Ukraine is rich. Global lithium sales last year were just $37 billion – down 22 per cent over the previous year on the back of oversupply and weak demand. Ukraine’s only graphite mine, sunk in 1934, suspended operations last December over falling world prices. In 2023 the entire world market for titanium amounted to just $31 billion. Ukraine may have 7 per cent of the world’s reserves of the hard, super-light metal – but it currently exports just 0.3 per cent of global supply.

Ukraine also faces the problem of who controls these deposits. Some of the largest troves of lithium ore – at Kruta Balka in the Zaporizhia region – are under partial Russian occupation. Ukraine’s undoubtedly enormous untapped reserves of natural gas span the north of the Donets river basin, also mostly occupied. Same for its richest reserves of anthracite coal in Soviet-era mines around Donetsk which have been beyond Kyiv’s control since 2014.

The source for the myth of Ukraine’s epic mineral riches was a November 2024 study called ‘Ukraine: Critical Minerals Portfolio’ put out by the Ukrainian government. Formatted like an investment pitch-deck, the report presented Ukraine as a literal gold mine for its future partners. The intention was to engage with the newly-elected Trump team in Washington. It ended with a personal message from Zelensky that Ukraine was ‘The greatest opportunity in Europe since World War II.’ Weeks after, that message was echoed and amplified by another report by a Lithuanian-based NGO which, though not formally affiliated with Nato, styles itself the Nato Energy Security Centre of Excellence. This report claimed that Ukraine’s minerals were ‘vital for nations aiming to lessen reliance on non-democratic countries like China, Russia, Iran, and other non-democratic regimes… the strategic importance of Ukraine’s critical materials cannot be overstated.’

Kyiv’s pitch worked. Ukraine was ‘the richest country in all of Europe,’ Republican Senator Lindsey Graham announced excitedly last December, claiming that Kyiv was sitting upon ‘$2 to $7 trillion’ worth of minerals. The Pentagon had made a similar claim back in 2010 when it announced that Afghanistan was also sitting on a trillion dollars of lithium, enough to make it the ‘Saudi Arabia of lithium.’

Both Graham and the Pentagon were wrong, and for the same reason. Mineral ore in the ground is not the same as refined metals shipped to customers. World demand is finite. ‘Tens of billions of dollars will have to be invested into the strategic metals sector to turn it into revenues,’ writes Ben Aris of BNE Intellinews. ‘And it’s not clear where this money will come from.’

Yesterday Trump boasted that he was about to sign ‘a big deal, very big deal’ with Zelensky. Reportedly the current draft calls for the creation of a Ukraine ‘Reconstruction Investment Fund’ backed by 50 per cent of all revenue from the extraction of minerals, oils and gas. It also declares that ‘the Government of the United States of America intends to provide a long-term financial commitment to the development of a stable and economically prosperous Ukraine – so as to invest in projects in Ukraine and attract investments to increase development.’ The deal also includes a US commitment to keeping Ukraine ‘free, sovereign and secure.’

The optimistic scenario is that the deal will open the door to US firms investing the vast sums needed to rebuild Ukraine’s shattered mines and transport infrastructure, as well as sinking new mines and building up the vast industrial infrastructure needed to refine it. That will give US businesses – and the government – a material vested interest in Ukraine’s future security, as well as creating jobs and opportunities for a war-shattered country. A revamped metal and minerals sector will also help wean Kyiv off its critical dependence on Western aid – currently close to half of Ukraine’s public servants’ salaries are paid for by the EU – and also help the country build its defences.

But the idea that Ukraine’s minerals are some kind of get-rich-quick bonanza for rapacious American capitalists is simply untrue. Kyiv’s resources undoubtedly have value. But it will be a long, hard and expensive slog to get them out of the earth and transformed into ready cash.

Badenoch accuses Starmer of ‘patronising’ her

It is getting rather repetitive writing that Kemi Badenoch had an uncomfortable Prime Minister’s Questions, so how about this: today’s PMQs showed that Keir Starmer does not regard the Conservative leader as any kind of political threat. He openly ridiculed her in his answers – perhaps too openly to appear statesmanlike.

The question that invited that ridicule followed a fairly benign one on ensuring that Ukraine be at the negotiating table in talks on the country’s future. Badenoch told the Commons she would then turn to the details of the defence spending announcement, saying:

Over the weekend, I suggested to the Prime Minister that he cut the aid budget, and I am pleased that he accepted my advice. It’s the fastest response I’ve ever had from the Prime Minister. However, he announced £13.4b billion in additional defence spending yesterday. This morning his defence secretary said the uplift is only £6 billion. Which is the correct figure?

Starmer rose:

I’m going to have to let the Leader of the Opposition down gently. She didn’t feature in my thinking at all. I was so busy at the weekend that I didn’t even see her proposal. She’s appointed herself, I think, the saviour of the western civilisation. It’s a desperate search for relevance. If you take the numbers for this financial year and then the financial year 27-28, that’s a £13.4 billion increase. That is the largest sustained increase in defence spending since the cold war.

Badenoch came back, complaining that Starmer wasn’t being clear, which was an odd verdict on an unusually clear answer. She then said that the Institute for Fiscal Studies had said the government was playing ‘silly games with numbers’ and asked him for the difference. Starmer continued to ridicule her:

We went through this two weeks ago in going through the same question over and over again, so let me say this again. If you take the financial year and then you take the financial year for 27-28, the difference between the two is £13.4 billion. That’s the same answer. If you ask again I’ll give the same answer again.

Badenoch was not happy. ‘Mr Speaker, someone needs to tell the Prime Minister that being patronising is not a substitute for answering questions. He hasn’t answered.’

Starmer told the chamber she was asking the same question again, and gave the same answer, then said the second part of her question was ‘serious’, which was about Ukraine. He added that there needed to be ‘security guarantees’ for Ukraine and that ‘we are working on that’ but was not in a position to put details before the House ‘as she well knows today’.

The Tory leader then said the Conservatives wanted to support the raise in spending, but needed the detail. She asked whether the additional spend would include the Chagos deal. Here, Starmer really could have given a very clear answer, but instead he offered a long lawyerly response where he explained ‘the funding I announced yesterday is for our capability to put ourselves in a position to rise to the generational challenge’ – but he didn’t say no.

Badenoch complained that the government plan for raising defence spending was ‘too slow’, and asked the Chagos question. Starmer said he had ‘just dealt with that’, and then offered his long lawyerly answer. He added, rather Trumpishly, that Badenoch ‘gave what people described as a rambling speech yesterday’ – making clear that he hadn’t bothered to pay it any attention himself.

But other Tory MPs had been paying attention to Starmer’s own rambling answers, and later in the session Kieran Mullan asked him to explicitly rule out using money from the defence budget for the Chagos Islands deal. Starmer did not do that, offering the same formulation of words about what the money was for, while not saying what it was not for. Meanwhile former chancellor Jeremy Hunt wanted a timetable for raising defence spending so Starmer could ‘look the president in the eye and say that Europe is finally pulling its weight on defence’. Starmer agreed about the importance of Nato, but didn’t give Hunt a timetable. Badenoch was right about the need for more detail on defence: it’s just that she failed to ask the right questions to expose that.

Keir Starmer is right to cut foreign aid

It was inevitable that the announced cut to Britain’s international aid budget would cause a stir. The curtailment earlier this month of the USAID programme provoked outrage among progressive voices worldwide, despite the fact that scheme funded some dubious causes. Why, then, would our compassionate classes react any different?

Yesterday, Prime Minister Keir Starmer explained that his plan to increase defence spending would be partly balanced by a reduction in the aid budget, from 0.5 per cent to 0.3 per cent of GDP. Some of his Labour colleagues aren’t happy. Sarah Champion, the Labour chair of the international development committee, reacted: ‘Conflict is often an outcome of desperation, climate and insecurity; our finances should be spent on preventing this, not the deadly consequences.’ Elsewhere, Clare Short concluded her thoughts on the matter: ‘I am afraid that, in many respects, this is simply not a Labour government’.

These countries do suffer from poverty, but that should be a problem for their governments to address

Further afield, Romilly Greenhill, the chief executive of Bond, which represents British aid organisations, denounced this ‘shortsighted and appalling move’ which would ‘have devastating consequences for millions of marginalised people worldwide’. The broadcaster Marina Purkiss lamented on LBC that ‘we are going to take money from the poorest countries on earth’ at a time ‘we’ve seen an enormous explosion of wealth in this country’.

Purkiss was implying that we have in Britain a sufficient number of people who can afford to share their riches, both with people overseas and at home. But the argument that the state is able to give money to countries abroad owing to ‘an enormous explosion of wealth’ here will not wash. It doesn’t remotely reflect a general sentiment in Britain today. This is not a nation luxuriating in its own opulence.

The incoming Trump administration, which does seem grounded on domestic matters, took an axe to the USAID scheme, which was given to questionable munificence – including a DEI scheme in Serbia, sex change programmes in Guatemala, conceptual art classes for Afghan women. This was because it understands that the American public largely detests these vanity projects, schemes designed foremost to boost the egos of those doing the giving, rather than improve the material lot of those receiving.

Likewise, much of the British public has come to regard foreign aid with suspicion, a mood that has grown to one of hostility and exasperation. This is especially the case when aid is not only spent on vacuous projects, but when it is given to countries that can well afford to do so themselves.

The British government currently spends £13.3 billion a year in foreign aid. As Douglas Murray pointed out recently, while £60 million of this figure has been used to prop up a ‘prosperity fund’ in Mexico (which has the 15th largest economy in the world), money from this pool has also been directed to China (2nd largest economy in the world), to help an all-female traditional Chinese opera in Shanghai ‘engage new urban audiences’. Funds have also headed to Shenzhen for a ‘space’ to encourage locals to get more involved in their ‘traditional crafts’.

If an emergent super-power wants to indulge in this kind of thing, so be it. But the British public is irked when their money is squandered by others in this way. The same rule applies to India (5th largest economy in the world), a country with nuclear arms and a space programme. Yet the UK has given £114 million to the country in the past three years ‘for inclusive green enterprises’. Britain has given neighbouring Bangladesh more than £133,000 for it to study shrimp health. Meanwhile, in December, the Foreign Office paid a contractor £9.5 million to support ‘accountability and inclusion’ in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

These countries do suffer from poverty, and India’s rise to riches in recent years masks shocking levels of inequality, but that should be a problem for its government to address. And whether any underprivileged demographic – anywhere – needs or deserves lessons in ‘equality and inclusion’ is suspect from the outset.

Not for the first time, the emotive imperative to be seen to care, to appear good rather than primarily or necessarily do good, has raised its head. We saw this come to the fore in the 1980s, with Band Aid and Live Aid urging us to give money, much of which, as a 2010 BBC Panorama investigation reminded us, ended up with Marxist ideologues, followers of an egalitarian creed that had helped to cause the famine in the first place.

After Diana, emotion still pulls the heart-strings. An allied ‘something must be done’ mentality persists, too, not least among advocates of ‘soft power’, a vague phrase and nebulous ideal, one with no defined or explicit aim. Pleas for foreign aid today feel like virtue signalling raised to the next level, elevated to a global mission.

How independent are Britain’s nukes?

Keir Starmer has sought to get into Donald Trump’s good books by boosting defence expenditure – and doing it in a very Maga way: slashing the UK aid budget to pay for it. That has no doubt caught the eye of the US president, as has the Prime Minister’s promise to put British boots on the ground in Ukraine as part of a European peacekeeping force after a deal is struck.

Mind you, that assumes that Vladimir Putin will keep to any deal to end the war. What if he doesn’t? Who guards the peacekeepers? Trump has made clear that European nations will have to look to their own security in future against an expansionist Russia. It’s not at all clear that America would send troops to stop Putin bullying, for example, the Baltic states, which have substantial Russian-speaking minority populations – or that President Trump would authorise the use of the full arsenal of US nuclear weapons against Russia if Putin delivered on his threat to use tactical nukes on the Ukraine battlefield.

Britain and France are the only nuclear powers in Europe capable of providing a credible deterrence to that threat. Germany wants the two nuclear nations to collaborate on an umbrella covering the whole of Europe. But just how independent is Britain’s independent nuclear deterrent?

The UK has command and control of these weapons, meaning that, in theory, we could launch the Trident missiles from any one of our four Vanguard nuclear submarines stationed at His Majesty’s Naval Base (HMNB) Clyde. The UK also controls the Royal Naval Armaments Depot (RNAD) Coulport, where warheads and missiles are stored for loading and unloading onto the submarines. One of these submarines is always at sea, providing what is called ‘continuous-at-sea deterrence’.

However, it’s not entirely clear that Britain could actually launch a nuclear war without the support of the US president. Our 50 Trident II D5 missiles are American and only leased by the UK. We collect them from a pool shared with the US at Kings Bay, Georgia, and they regularly return there for maintenance and upgrading.

The warheads are British, having been developed and maintained at the Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE) Aldermaston – which used to be the target of annual Ban the Bomb marches half a century ago. However, developing them is a joint exercise with the US firm Lockheed Martin. The guidance systems are also American, as is the network of satellites that are essential for accurate targeting.

Would Donald Trump be happy with the UK threatening to use nuclear weapons against his new mate Vladimir Putin? The question has to be asked because there are any number of ways that a US president could prevent the UK using nuclear weapons, or undermine confidence that they could be used independently of US support. He could simply ask for ‘his’ missiles back, or refuse software updates to the targeting systems.

This all seemed rather academic in the past since it was assumed that Britain’s nukes would only be used as part of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato). Under the Nassau Agreement of 1962 between John F. Kennedy and Harold Macmillan, Britain agreed to formally assign its nuclear forces to the defence of Nato, except in an ‘extreme national emergency’. No one bothered to ask what an extreme national emergency would look like since the weapons were there to deter the Soviet Union; no one thought Britain would go to war unilaterally.

All that has changed. There is now a hot war in Europe, during which Russia has made clear that it could use tactical nukes on the battlefield. It has deployed nuclear weapons in Belarus in defiance of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. Europe now has a regional nuclear threat to contend with – just as the US appears to be withdrawing from Nato’s Article 5 commitment to declare war if any member state is attacked.

If Britain’s nuclear weapons are to provide the backstop that other European nations want, Keir Starmer is going to have to seek cast-iron guarantees – if such a thing is possible – that the UK’s nuclear weapons can retain US support come what may. During the cold war, politicians and commentators used to debate ‘whose finger’s on the button’. In 2025, it looks rather as if it is President Trump who controls the off switch.

Chagos judge also supported slavery reparations

Well, well, well. It turns out that an international judge who ruled against Britain on the Chagos Islands has also, er, called for the UK to pay over £18 trillion in slavery reparations. Patrick Robinson is a Jamaican judge who has previously served on the International Court of Justice – and was one of the judges who, in 2019, agreed the UK should hands over the archipelago ‘as rapidly as possible’. How very curious…

As reported by the Telegraph, Robinson is a big supporter of Britain paying reparations to African and Caribbean countries for slavery – and even helped write a recent United Nations report that proposed the UK should give away over £18 trillion as part of a £87 trillion payment from ex-slaveholding countries. In fact, at the time, the lawyer said the sum was an ‘underestimation’ of the pain inflicted by Britain during the slave trade – and he insisted to the Beeb that ‘once a state has committed a wrongful act, it’s obliged to pay reparations’. Goodness.

The news comes as it transpires that lawyers for Mauritius have argued that the UK would be partaking in ‘decolonisation’ by ceding sovereignty of the Chagos Islands. And, Mr S would note, the ICJ ruling that the islands should be transferred to Mauritius, is one of the primary arguments that supports Britain’s relinquishing of the archipelago.

As Steerpike reported at the start of the month, rumours of the deal that Sir Keir Starmer was proposing – to offer out the Chagos Islands for billions and give ‘complete sovereignty’ of US naval base isle Diego Garcia to Mauritius – sparked outrage. Reform leader Nigel Farage took to Twitter to blast the PM, writing: ‘This is a dreadful decision by Starmer. Our relationship will be in tatters when the USA wakes up to what our Prime Minister has done’. Meanwhile shadow justice secretary Robert Jenrick branded it the ‘worst deal in history’. Will yet more money be offered to Mauritius to take the islands back? Watch this space…

Trump reveals glamorous Gaza vision

To Donald Trump. The US president has shared a rather interesting video on his Truth Social platform, depicting an AI-generated Palestine with the caption: ‘Gaza 2025… What’s next?’. The president has hinted before about how his nation could rebuild the country – and this generation appears to show just how he expects that project to turn out…

A computerised version of the Middle Eastern country – which, according to Sky News was first shared in early February with no apparent connection to the White House – shows the area transformed into an exotic haven filled with beaches, skyscrapers, yachts and parties. From a ‘Trump Gaza’ tower to a huge statue of the US leader, no expense appears to have been spared in the rather bizarre video. Elon Musk, the tech billionaire owner of Twitter and co-leader of the Department of Government Efficiency, pops up a number of times in the footage – with the US businessman seen enjoying humous and flatbreads on the beach and walking through a mist of dollars.

Trump himself features a rather lot – whether he’s sipping cocktails with Israel’s Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, or dancing with a scantily-clad belly dancer in a nightclub. In the background, a song about the President plays, with the lyrics noting:

Donald’s coming to set you free, bringing the light for all to see, no more tunnels, no more fear: Trump Gaza’s finally here / Trump Gaza’s shining bright, golden future, a brand new life / Feast and dance the deal is done, Trump Gaza number one.

It comes after the US president had Netanyahu visit as the first foreign leader to the White House earlier this year. After the meet, Trump held a press conference in which he declared that the US would ‘take over’ Gaza, adding:

Everybody I’ve spoken to loves the idea of the United States owning that piece of land, developing, and creating thousands of jobs with something that will be magnificent in a really magnificent area that nobody would know. Nobody can look because all they see is death and destruction and rubble and demolished buildings falling all over. It’s just a terrible, terrible sight. I’ve studied it. I’ve studied this very closely over a lot of months, and I’ve seen it from every different angle. And it’s a very, very dangerous place to be, and it’s only going to get worse.

Crikey. Will Trump’s dream vision of Palestine transpire? Watch this space…

What does Trump’s minerals deal mean for Ukraine?

Has Donald Trump’s heavy-handed negotiation style scored a win, or have the Ukrainians managed to wrench a victory of sorts from the jaws of defeat?

Although the details are still unclear, Kyiv and Washington are confirming that a deal on mineral rights has been agreed, and that Volodymyr Zelensky will be on his way to the White House on Friday to sign on the dotted line. Trump has abandoned his ludicrously overblown demand for a $500 billion (£400 billion) return on what has actually been no more than $120 billion (£95 billion) given in total aid, through revenue from Ukrainian oil, gas and rare earth metals. Zelensky had understandably rejected this, saying ‘I am not signing something that ten generations of Ukrainians will have to repay.’

Instead, it seems that a fund for the reconstruction of the country will be established, with a substantial US stake, which will draw on a share of those revenues. The precise terms of the deal and the American share have yet to be confirmed, but it is clearly less onerous and humiliating than the original demand. It does not include though the long-term security guarantees that Kyiv had previously demanded as part of the deal. Still, the Ukrainians are hoping that by giving the Americans a vested economic interest, it will incentivise Trump, who continues to think more in terms of balance sheets than geopolitics, to think of their security.

This will not mean an instant bonanza for either Ukraine or the USA. Most of the country’s mineral resources are, after all, in the east of the country, and either now under Russian control or else close enough to the front line that efforts to develop and exploit them would essentially require an end to the fighting. In many cases, they will also need investment to exploit.

Nonetheless, it does provide some hope for Ukraine that Trump is not looking to write them completely off. When asked what the deal gives the Ukrainians, he said ‘the right to fight on’.

Ukrainians don’t need Washington’s permission to fight on, but they do need continued US assistance, and this provides a welcome counterbalance to the spectacle on Monday of the USA siding with Russia to vote against a European-drafted resolution at the United Nations condemning Moscow’s invasion. Meanwhile, Trump gets to promise his America First base that he has won them a return on their investment, their money back ‘plus’.

This is a small mercy, but at least it means that Ukrainian security has not entirely been forgotten. A Ukrainian diplomatic source sighed that it was ‘better than I had feared, although not as good as I had hoped.’ Trump said that seccurity was an issue to be addressed ‘later on’, but with characteristic bravado added, ‘I don’t think that’s going to be a problem. There are a lot of people that want to do it, and I spoke with Russia about it. They didn’t seem to have a problem with it.’

Would that it were so simple. After all, while his forces are still grinding away on the front line, Vladimir Putin is also slyly trying to outbid Zelensky. He has proposed a deal to develop Russia’s mineral resources – and he would want to include those in the occupied Ukrainian territories – adding that Russia ‘undoubtedly’ has ‘significantly more resources of this kind than Ukraine’. This is probably a non-starter (though in Trumpworld, ‘probably’ is about as certain as anyone can be about anything), not least because an American president, unlike his Russian counterpart, cannot order companies to sign deals. Mindful of the legal and reputational risks of operating in occupied lands, as well as the losses suffered by other companies that were either forced to leave Russia or targeted by the Kremlin, it’s unlikely any would even contemplate this before a full peace deal had not only been signed but seemed to be holding.

More than anything else, it is a reminder of Trump’s overtly transactional approach and his unabashed use of America’s military and economic muscle. He opens negotiations with a tough, unrealistic bid, because he expects to be haggled down, but he ultimately wants to make a deal. This makes his position towards Moscow seem, on the face of it, contradictory or, to those still convinced he is somehow being controlled by Putin, suspicious. Yet it need not be so difficult. Trump will do what he feels he has to do to open negotiations, blithely convinced he can make a good deal. He offered concessions that weren’t really concessions – pretty much everyone knew that Ukraine would not be joining Nato in the foreseeable future, or reconquering all the occupied territories – to get Putin to the table. Whether he can make a deal, let alone a good deal, remains to be seen.

Will Trump’s ‘golden visas’ threaten Rachel Reeves’s tax plans?

Fed up with Rachel Reeves’s tax rises, with the calls for wealth and mansion taxes, and the loss of non-dom status? For $5 million (£3.95 million), there is now a very easy escape route. President Trump has just announced a ‘golden visa scheme’, allowing investors an easy path to American citizenship. That is aimed at attracting global entrepreneurs to the US. But it could also pose a real threat to the British economy.

The UK depends on a small group of taxpayers to keep its huge state machine financed

It is certainly a dramatic move. Golden visas that allow citizenship in return for investment have traditionally been restricted to a handful of micro-states and tax havens. President Trump has now decided to add the United States to the list. We will see how successful this is. Compared to places such as Dubai, the Caribbean islands, and Malta, best known for their golden visas, American taxes are relatively high. The footloose, tax-averse global mega-rich may just decide a US passport is not worth having.

In reality, the country that might be really hit is the UK. Sure, the visa will only appeal to a small pool of people. After all, not many of us have $5 million to spare. And yet, for anyone who does, the US is the country that the wealthy British have always found it easiest to move to. It has a vast range of cities to choose from, everyone speaks the same language, it has huge commercial opportunities, and world-leading universities. Most people already have friends and family in America. It is not a tax haven, of course, but taxes are significantly lower than they are in the UK, and under the Trump administration they are coming down. The people who are not sure about Dubai or Monaco may find it very appealing.

The real problem is this. Over the last 20 years, the UK has dramatically narrowed its tax base relying on collecting more and more money from the well-off. Sixty of the wealthiest people pay more than £3 billion a year in income taxes, according to a report by the BBC. They account for just 0.0002 per cent of UK taxpayers but paid 1.4 per cent of the country’s total income tax receipts. Likewise, last year, the top 1 per cent of income tax payers paid 28.2 per cent of income tax, up from 22.7 per cent twenty years ago.

In effect, the UK depends on a small group of taxpayers to keep its huge state machine financed. The Greens, the Liberal Democrats and the Labour Left keep arguing for that to be increased, insisting that the ‘rich’ should pay even more. But President Trump has just effectively put a cap on that, by offering them the US as a refuge. That will make it very hard for a British Chancellor to push taxes on the ‘wealthy’ any higher – indeed at some point she may even be forced to reduce them.

Ukrainians are keeping calm and carrying on in defiance of Trump

In 2023, I had coffee with the celebrated Ukrainian novelist Andrey Kurkov, on Yaroslaviv Val Street in the ancient heart of Kyiv. The modern city is built over the ruins of the rampart built by Yaroslav the Wise, the eleventh-century Grand Prince of Kyiv, to keep out invaders. Now, on the third anniversary of the most recent invasion of Ukraine, Kurkov, whose novels are known for their dark humour, is in a much more sombre mood. Donald Trump’s savage and surreal attacks on president Zelensky have left the country reeling.

‘Of course, Ukrainians are shocked and upset,’ he says. ‘If two weeks ago Russia considered Americans and Poles their main enemies, now Trump has moved Americans almost into the camp of Putin’s allies.’ Yet Kurkov sounds a note of defiance that will be familiar to anyone who has spent time in the country.

‘The rest of the world is playing funeral music but still Ukraine is not prepared to give up and to succumb to the Putin-Trump effort. The military say the war will go on and they are ready for this.’ It’s stirring stuff and the optimism remains contagious. It is only his final words that feel unconvincing: ‘This is also a chance for the European Union to become stronger and more united.’

My friend Maria Avdeeva, security expert, social media warrior and senior Eurasia fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, shares the sense of outrage at Trump: ‘It’s ridiculous, everyone is shocked.’ Beyond the disbelief, however, is the sense that Trump is getting the fundamentals wrong in his quest for a deal. There’s no evidence that Putin wants to end the war or achieve anything other than complete control of Ukraine, she says. It misses the point to focus on whether Russia keeps the territory it has taken. ‘Putin wants to put in a puppet government and make us a satellite state like Belarus. He wants Ukraine not to exist as an independent state.’ Trump’s tirade against Zelensky has had the predictable effect of rallying support for the embattled president. Maria sends me a link to Zelensky’s ‘Thank you for your support!’ post on X. It has 12 million views and 377,000 likes.

Roman Hnatiuk, a lugubrious businessman, has given up checking his media. ‘I can’t read the news,’ he moans, over a bowl of borscht. We are in Spelta, a hip bakery-turned-restaurant in Podil, Kyiv’s answer to Greenwich Village. ‘I’m serious. I get sick in the stomach, I don’t know what’s going to happen to Ukraine, Europe, the world. The worst scenario is for us to be pushed into elections and pro-Russian populists come to power. Then we repeat the Georgia scenario. With the number of weapons in Ukraine, that means civil war.’ First America pushed Ukraine to give up its nukes and promised it independence. ‘Now they’re ready to sell us to Russia. One thing I know for sure is that if America insists, Europe, the West, everybody, will sell us down the drain.’

One positive consequence of Russia’s invasion, which Trump’s scuttle will only accelerate, is the meteoric rise of Ukraine’s defence tech industry. In subzero temperatures, 3,000 parka-clad arms dealers, entrepreneurs, spooks and hacks from 40 countries descend on Mystetskyi Arsenal, a handsome (and appropriate) repurposed venue for the largest event in the sector’s history. Welcome to the world of advanced robotics, autonomous AI-driven drones, anti-radiation autopilot systems, laser weapons, visual inertial odometry, Raptor EO/IR gimbaled sensors, kamikaze swarming drones in GNSS-denied environments, distributed acoustic weapon location systems and other mind-spinning innovations. Strix Air, which provides radio control technology for drones, cuts through the jargon with a succinct summary of its product: ‘Your assistant in killing more Russians.’ ‘Ukraine has the capability to produce effective, innovative defence solutions at scale and at a fraction of the cost of similar systems from abroad,’ says Artem Moroz of Brave1, the government’s defence tech platform. ‘In the future, this industry can become a cornerstone of Ukraine’s economic recovery and a reliable arsenal for Ukraine’s allies from Europe and overseas.’ The West should take note.

Is tech really the answer to this war? Misha Rudominski, twentysomething entrepreneur and co-founder of Himera, the encrypted tactical radio manufacturer, thinks so. Like most of Ukraine’s would-be tech titans, he’s not letting Trump distract him and is focused instead on securing $1.5 million (£1.2 million) from venture capitalists. Himera already supplies the Ukrainian armed forces and is now dipping its toes in foreign markets, starting with the US Air Force, Estonia and the Philippines. Perhaps it’s the optimism of youth, but Misha is remarkably sanguine about the prospect of Ukraine going it alone without Uncle Sam. ‘Most battlefield kills these days are from Ukrainian technology – deep strike drones, FPV drones, any kind of drone,’ he says. ‘In 2022, without US help it would have been all over, same in 2023, less so in 2024. Now, with Ukrainian tech and European funding, we can sustain this fight.’

With the costs of weaponry manufactured in Ukraine five to ten times cheaper than the American equivalent, he reckons Europe could bear the costs. He’s probably right, but will Europe agree to it?

I’ll give the last word on Trump’s geopolitical blitzkrieg to Oleksandr, my mole in the special forces. ‘We’re not worried about it so much,’ he says, gloriously unruffled as ever, as Russia launches a massive drone attack on Kyiv. ‘I think the Americans should be more worried. It’s their country (Trump’s) going to destroy. We’re just going to carry on fighting.’

How North Korea will use its $1.5 billion of stolen crypto

For a country that is notorious for its lack of connection to the outside world, North Korea is one of the world experts in cyberwarfare.

Only this week, North Korean hackers managed to steal $1.5 billion from the cryptocurrency exchange Bybit, in what is the largest cryptocurrency hack on record. The fact that the stolen money is just over 5 per cent of the country’s GDP does not mean the profits will be going to the North Korean people or economy though. After all, nuclear weapons and missiles hardly come cheap.

There has been a deluge of North Korean cyberattacks in the 21st century. The country even has its own state-run cyberwarfare agency, the elusive ‘Bureau 121’, which forms an integral part of the Reconnaissance General Bureau, the country’s central intelligence agency responsible for managing and orchestrating clandestine intelligence operations. Bureau 121 was established in the late 1990s, and is explicitly tasked with conducting cyber disruption, such as infiltrating computer networks. The bureau quickly became infamous for hiring the brightest and the best minds, not least from young North Koreans studying computing at universities.

One of the most notable North Korea groups responsible for carrying out cyberattacks has been the so-called Lazarus Group, also known (ironically) as ‘Guardians of Peace’. Supported by the North Korean government, it has been responsible for many North Korean cyberattacks in the last two decades. Who can forget how in 2014 the Seth Rogen film The Interview – where two American journalists meet Kim Jong Un in North Korea and eventually manage to assassinate him – was stymied by a successful attempt to hack into the computer systems of Sony Pictures. Confidential data was leaked, including personal details of Sony employees and future film scripts. The not-so-peaceful Guardians of Peace demanded that Sony withdraw the film from public distribution and even threatened terrorist attacks on cinemas that showed the movie. The film’s intended premiere date in New York was postponed.

As technology has evolved, so too have North Korea’s tactics. Pyongyang initially targeted South Korean government websites and came close to raiding the Bangladeshi Central Bank. It then launched ransomware cyberattacks – such as the WannaCry malware of May 2017 which affected NHS computers – and began targeting journalists and academics with phishing campaigns. As the world became obsessed with cryptocurrency and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) so too did North Korea. In March 2022, the Lazarus Group orchestrated a major heist, wherein it acquired $620 million in cryptocurrency from the NFT-based video game, Axie Infinity. Yesterday’s theft, of over double that amount, sets a concerning precedent.

Before the first Trump administration began in 2017, Barack Obama made clear to his successor how big a problem North Korea would be. Over seven years have passed since then, and the North Korean threat is now increasingly complex. For all the West’s efforts to sanction North Korea’s bad behaviour, the hermit kingdom continues to find ways to evade them. One of the targets on the FBI’s wanted list is Park Jin Hyok, a member of the Lazarus Group who allegedly played a central role in the 2014 Sony Pictures and 2017 WannaCry ransomware attacks. Park may also have been the mastermind behind this week’s theft. But the FBI’s arrest warrant has just been ignored by North Korea. In Pyongyang’s view, Park simply does not exist.

Illicit cyber activities have funded at least half of North Korea’s weapons of mass destruction programmes

Meanwhile, North Korea’s cyberwarfare campaign looks set to continue. It is a highly lucrative means of funding its nuclear and missile capabilities. As of January 2024, illicit cyber activities have funded at least half of North Korea’s weapons of mass destruction programmes which, in addition to nukes, also includes biological and chemical weapons.

Pyongyang’s renewed rapprochement with Moscow could mean things get worse. The Moscow-Pyongyang relationship is not just restricted to the exchange of munitions and manpower in return for oil, food, cash, and advanced missile technology. The possibility of these two rogue states engaging in cyber cooperation cannot be ruled out. You only need to read the ‘comprehensive strategic partnership treaty’ signed between the two countries in June last year to see why. It not only contained a mutual defence clause, but saw both states pledge to strengthen cooperation in ‘information and communication technology security’.

It is therefore vital that the West takes the North Korean threat seriously. The West – which includes Britain – cannot be seen to be afraid of our enemies. We instead need to act reliably and robustly, while standing true to our values of democracy, freedom, and prosperity.

Starmer’s surprisingly ruthless foreign aid cut

Ten years ago the idea of a British prime minister announcing a cut in foreign aid to 0.3 per cent of GDP would have been unthinkable.

David Cameron’s Tories had exempted the Department for International Development from austerity, repeatedly declaring that it would be wrong to balance the books on the backs of the world’s poorest people. Naturally, Cameron’s coalition partners the Lib Dems supported this stance, while Labour revelled in having been the party that raised aid spending to this level and legislated to create a legal duty for subsequent governments to maintain it.

The case for radically cutting the aid budget only saw the light of day in the 2015 Ukip manifesto, to which I contributed. We suggested a reduction from 0.7 per cent of GDP to 0.2 per cent and were of course pilloried as vile for doing so. Given the proportion of the aid budget currently being spent at home on tens of thousands of asylum-seekers, this Ukip policy is in effect what has just been announced by 10 Downing Street. By a Labour prime minister.

Even given the security context, requiring big extra spending on defence, this is the most right-wing thing a Labour premier has done for decades. David Miliband, the Blairite prince over the water with a vested interest in the aid industry, has gone on the record to state his opposition to the move, saying: ‘Now is the time to step up and tackle poverty, conflict and insecurity, not further reduce the aid budget.’

Yet Keir Starmer is completely unabashed by it. He has even underlined the thinking behind his decision via an exclusive article for the once hated Daily Mail.

So we may safely conclude that something political is going on beyond the simple need to be seen to better fund our armed forces in the future. The veteran Labour-watcher Andrew Marr hinted at this in a column for the New Statesman a couple of weeks back in which he drew attention to a series of moves to the right by Starmer, starting with the publication of a government video showing illegal immigrants being deported. This in itself told us something about Starmer given his hostility towards immigration control measures throughout his career as a radical lawyer and even during his early years in Parliament.

What these two moves – cutting aid and upping tough-talk on defending the borders – point to is the extraordinary ruthlessness of this Prime Minister, even by the standards of those who reach the very top of the greasy pole of politics. Marr pointed towards fear of Nigel Farage’s Reform, now topping the polls, as a major motivating factor, along with an appreciation that the election of Donald Trump had changed the political terms of trade all over the world. In which case, just as on the road to Brexit, Farage’s ability to force incumbent premiers who detest his politics to bend to his will must be appreciated as a thing of wonder.

Given Labour’s collapsing poll ratings, perhaps Starmer has asked again the question he posed of others with better political antennae after Labour’s catastrophic by-election defeat in Hartlepool in the spring of 2021: ‘Why does everybody hate us?’ The answer now would be the same as back then: Labour is too metropolitan, too left-wing, and too absorbed in anti-British identity politics and cultural ‘progressivism’.

The most interesting question now is where this shift to the right will show up next, because show up it most certainly will. Perhaps it will be in a sweeping cabinet reshuffle that removes or marginalises the likes of Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson and Attorney-General Richard Hermer, two of the Government’s most dogmatic leftist culture warriors. Perhaps it will be in further and equally significant changes of policy.

Soon it may not only be David Miliband finding Starmer’s new politics unconscionable, but Ed Miliband too. Because energy and climate change policy is clearly at the heart of Britain’s industrial malaise and living standards crunch. Surely a Labour prime minister could never slow down the dash to net zero? Think again. This Labour prime minister will do almost anything to try and save his own skin.

The Climate Change Committee is living in cloud cuckoo land

Energy bills may be going up and the economy may be flatlining, but not for long. Thankfully, the government’s Climate Change Committee has the answer. In a press release introducing the committee’s Seventh Carbon Budget, published this morning, interim chair Piers Forster declares: ‘The committee is delighted to be able to present a good news story about how the country can decarbonise while also creating savings across the country.’ By 2040, when the CCC sees the UK’s carbon emissions falling by 87 per cent on their 1990 level, the cost of heating and lighting our homes is going to fall by £716 a year and the cost of running a car by £699.

Surely never has such a Panglossian document been put before the public by an arm of government. The CCC has progressed from making what a committee of MPs called ‘heroic assumptions’ into the realm of outright fantasy. The report can’t even describe the current situation accurately, so why we should believe its projections for 15 years’ time?

The report tells us, for example, that ‘for many technologies (including solar, wind turbines, and batteries) consistent and rapid cost reductions have been seen over the past 20 years’ – which will come as news to the civil servants who ran the government’s auction for offshore wind in September 2023 and received not a single bid. The then Conservative government had to increase the long-term guaranteed ‘strike prices’ on offer by 66 per cent. The price of wind power plummeted while interest rates were on the floor – and suffered a sharp reversal when rates went up.

Surely never has such a Panglossian document been put before the public by an arm of government

The document also claims that electric cars are ‘already cheaper to run and maintain than petrol or diesel and will shortly be cheaper to buy.’ That will come as a surprise to anyone trying to run an electric car from public chargers. And while the cost of running an electric car from your home supply can be lower than a petrol car, that rather ignores the tax situation – around half what you pay at the pump is fuel duty. EVs won’t be so cheap to run once the government comes up with new motoring taxes – probably road pricing – to claw back the £28 billion a year it faces losing in fuel duty. As for the claim that EVs will be on purchase price parity with petrol and diesel cars by 2026 to 2028, that skirts around that reality that recent discounts have been made out of desperation, as manufacturers try to avoid fines for not selling enough EVs under the Zero Emissions Vehicle mandate.

By 2040, the document claims, 63 per cent of HGVs are going to be electric. That is a dream figure given that there are hardly any electric lorries on the road at the moment, and the few light, 20 tonne lorries that are available can manage little more than 100 miles between charges (compared with 800 miles for diesel lorries). Moreover, Tevva, which was touted as the Tesla of trucks – which was going to manufacture them in Essex – went bust last year.

Similar fantasies are spun regarding carbon capture and storage, hydrogen and grid batteries, all of which are projected to play a significant role in balancing intermittent wind and solar power by 2040 – in spite of playing little or no role at present on account of their excessive cost. How these costs are going to come down so dramatically that they will save us £716 on our energy bills the CCC doesn’t explain.

But there is another striking assertion in the CCC’s Seventh Carbon Budget. It projects that meat consumption in Britain is going to fall by 25 per cent by 2040, with the numbers of cattle and sheep plunging by 27 per cent as land is given over to trees to try to soak up carbon. Not such a prosperous future for farmers, then – while the rest of us, it seems, will have to be strong-armed into changing our diets. There is little sign at present of the population wishing to play along with this. On this, at least, the CCC shows a rare bit of insight. While it first welcomes an 11 per cent fall in meat sales between 2020 and 2022 it does then admit that this might just have more to do with eliminating waste during the cost of living crisis than a desire to change what we eat – given that overall food sales fell by 10 per cent over the same period.

If meat consumption does fall by 2040 it will more likely be down to us having to survive on bread and water. The golden low-carbon economic future portrayed by the CCC is simply not credible – though sadly it will fool many MPs just like its previous reports.

Europe can’t silence its working class forever

Last December the European Commission published its ‘priorities’ for the next five years. All the bases were covered, from defence to sustainable prosperity to social fairness. And of course, the most important priority of all, democracy. ‘Europe’s future in a fractured world will depend on having a strong democracy and on defending the values that give Europeans the freedoms and rights that they cherish,’ proclaimed the Commission, which pledged it was committed to ‘putting citizens at the heart of our democracy’.

December was the same month that a Romanian court cancelled the presidential election, after the surprise first round victory of the Eurosceptic and anti-progressive Călin Georgescu. It was claimed the election had been tainted by Russian interference. As Thierry Breton, a former European commissioner, boasted later on French television: ‘We did it in Romania and we will obviously do it in Germany if necessary.’

There will be no need to cancel the result of the German election. The Alternative for Germany (AfD) polled 20.8 per cent of the vote – double its score of 2021 – but still came in second behind the CDU.

In a healthy democracy, the AfD would now have a major influence on its nation’s politics having earned the support of one in five of the electorate. But Germany isn’t a healthy democracy. There is what Germans call a ‘firewall’, Brandmauer, which will shut out the AfD from any meaningful involvement in the many major issues confronting the country. Instead, Friedrich Merz is expected to form a coalition government with the Social Democrats, who came third in the election.

‘Friedrich Merz has decided to maintain his blockade stance towards the AfD,’ said AfD co-leader Alice Weidel. ‘We consider this blockade to be undemocratic. You cannot exclude millions of voters per se.’

One can in Europe, particularly when the voters are working-class. When it began its rise a decade ago, the AfD’s core voter was described as ‘likely to be male, middle-aged, relatively uneducated, blue-collar worker or unemployed.’

They have broadened their appeal since, particularly among the young: 21 per cent of 18- to 24-year-olds voted for the AfD on Sunday, more than any other party except Die Linke (The Left).

But the AfD continue to poll best among blue-collar workers. According to German broadcaster DW, in Sunday’s election ‘people with a basic education level were twice as likely to vote AfD as those with advanced degrees.’

Germany, of course, isn’t the only European country that ignores its working class. It’s been going on in France for years; a country whose national motto is ‘liberty, equality, fraternity’.

France’s firewall is called the ‘Republican Front’ and for decades it has been routinely erected at elections to keep the hoi polloi at bay, or as they’re otherwise known, Le Pen voters.

The average National Rally voter is similar to the AfD stalwart: middle-aged, in a blue-collar profession, with no higher education qualification and living outside a big city.

In last July’s French parliamentary election, the National Rally won 37 per cent of the popular vote, and they took 125 seats in parliament, making them the biggest single party. All other parties refuse to work with them. Many left-wing politicians even refuse to shake the hands of National Rally MPs; by extension, they are refusing to shake the hands of 37 per cent of their fellow citizens.

One of the most perceptive observers of the disintegration of democracy in France this century is the social scientist Christophe Guilluy. The book that established his reputation, La France périphérique [peripheral France] was published in 2014, and it explained how the metropolitan elite had lost touch with the working-class provinces.

A decade on, this disengagement is more profound than ever; I can testify to it, having moved 18 months ago from Paris to peripheral France, in my case rural Burgundy. The cultural chasm is huge. Paris might as well be another country and when Parisians venture into the provinces they stand out a mile.

The Paris elite make little attempt to conceal their contempt for the ploucs [yokels]. The Yellow Vest movement of 2018 began when the government introduced a green fuel tax. Cars aren’t that important to city dwellers but in the sticks – where there is hardly any public transport – they are vital. The government didn’t care. Its spokesman, Benjamin Griveaux, dismissed the protestors as ‘people who smoke cigarettes and drive diesel cars… not the 21st-century France we want’.

In an interview this week to promote his new book, Guilluy said that ‘the cultural centre of gravity of Western societies is tilting towards the ordinary majority’. In other words, the will of the Yellow Vest protestor is winning out over Benjamin Griveaux and his ilk.

Guilluy endorsed the gist of J.D. Vance’s recent speech in Munich, praising ‘the clarity of his thinking’. He added: ‘The main cause of the so-called “collapse or end of the West”… is first and foremost the consequence of the choice made by Western elites in the last century. The choice to exclude those who are the lifeblood of society, those who keep a culture alive and well: ordinary people.’

Germany’s ‘firewall’ and France’s ‘Republican Front’ are examples of this exclusion. So too was the cancellation of Romania’s presidential election.

The EU brags of ‘putting citizens at the heart of our democracy’ but in reality Brussels is interested only in the ‘right sort’ of citizen. Those that are progressive and globalist, the ‘Anywheres’ of this world.

The ordinary people, the ‘Somewheres’, are of no importance. But the Somewheres are on the march, in Germany, in France and all across Europe, and the firewall won’t hold for ever.

My strange day with the Palestine Solidarity Campaign

The day after the bodies of Ariel and Kfir Bibas were returned to Israel, the Palestine Solidarity Campaign (PSC) holds a protest outside Westminster Magistrates Court on the Marylebone Road.

I am here for the hearing of Ben Jamal, director of the PSC. He is charged with failing to comply with a police request that the January 18th protest avoid the BBC as it is near a synagogue. (The Palestine movement thinks the BBC is a Zionist asset, despite it having to remove a documentary narrated by the son of a Hamas official last week.) The PSC couldn’t stay away and their leaders were charged with public order offences after moving towards the BBC with flowers in their arms. My instinct is: they loved it.

Now they are protesting outside the court for the freedom to protest. You might think the PSC, which, with Stop the War, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, the Muslim Association of Britain and Friends of Al-Asqa, has brought central London to a standstill many times in the last 15 months is aware of its freedom to protest, but narcissists are insatiable.

I queue outside the court from 8 a.m. and they come up to ask if I think keffiyehs and badges are allowed in. They are dependent on costume: they communicate by slogan, signage and badge. They look like social studies professors at failing universities, or bad ceramicists. They initially smile, because they cannot grasp the idea of opposition, or even disagreement.

But Jewish children dear to me have been called ‘dirty Jews’ on London streets. This rarely happened before 2015, and I blame these protestors and associated cretins. There are respectable ways to advocate for Palestine, but they can’t do it because demonizing Jews is an ancient, if sometimes subconscious, European tradition. At the first PSC protest in my hometown Penzance I asked the leader what he wanted. He looked puzzled to be asked, and said he didn’t know.

Inside the court building I watch them from the window laying flowers, waving ‘EXIST, RESIST, RETURN!’ placards and listening to John McDonnell, Socialism’s Batman villain, and Chris Nineham who, as the Westminster and Cambridge-educated son of a former warden of Keble College, Oxford wins Affluent Socialist Bingo for all time. He is chief steward of the marches, and, by his own testimony not an anti-Semite, though he is seemingly unable to prevent blood libel signage and marchers making cut-throat gestures and Hamas triangles – the sign you are a target – at the Jewish counter protests. The protestors seem quite happy for people who think democracy is dying because they cannot protest near a synagogue on a Saturday.

Few come to the public gallery, possibly because placards and megaphones are not allowed in courtrooms. Jamal, who wears a leather jacket and an expression of startled yet sustained self-importance, pleads not guilty to a judge who looks uncannily like Julius from The Thick of It. Jamal asks not to give his address in public because he fears a counter-protest in Kingston-upon-Thames. The judge tells him not to use his phone in the dock, and I wonder if he is playing Candy Crush.

Later, outside, we wait for Jamal to exit. I meet a woman who thinks Palestine should be a secular state: a sort of Rainbow nation. I wish her luck with an endorsement from Islamic Jihad (or the Kahanists). I ask her if she minds that Europe and the Middle East is filled with empty Jewish quarters. She replies, though hesitantly, that might have something to do with the Holocaust. Well, yes. I tell her you can cross Israel in half an hour, and she gawps: does she think it is the size of Russia? A man notices my questions and tells her I am hostile. He appoints himself bodyguard, and when Jamal comes out he stands between us, preening in the manner of the silent who has learned to speak at last.

Coffee cups and placards litter the street. Don’t forget to take your rubbish home with you, I tell a woman as I leave. She replies that I am nasty: why do they talk like children? A masked man notices us and walks towards me, megaphone at his lips, to drown out anything I might say. I forget the slogan. I walk away, flipping the bird with two fingers.