-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

The assisted suicide bill’s shameful lack of scrutiny

Last November, when the House of Commons voted on her assisted suicide legislation, Kim Leadbeater told her colleagues that the Bill would face ‘further robust debate and scrutiny’, including ‘line-by-line scrutiny in Committee’. But judging by the disgraceful scenes at her Bill committee’s first formal sitting on Tuesday, Kim Leadbeater and her supporters have given up on any pretence of caring about scrutiny and fairness.

The procedural shenanigans began much earlier. First, Leadbeater, who gets to choose the committee’s membership as the sponsor of the Private Members’ Bill, subject to approval by the committee of selection, stacked it with strong supporters of assisted suicide (including five co-sponsors of her Bill and two government ministers who voted in favour of it), whilst turning down requests from experienced parliamentarians with relevant expertise to join the committee.

The handpicked committee belatedly issued a call for evidence in January, leaving little time for interested parties to send in submissions. Leadbeater then sent a list of witnesses for the committee to hear in person, only to submit a new list hours before its meeting this week.

Without any sense of irony, Leadbeater called her witness list ‘extremely balanced’. The numbers tell another story. Of the eight witnesses from foreign jurisdictions on Ms Leadbeater’s list, not a single one is opposed to assisted suicide, despite numerous foreign experts warning that Britain should not emulate their countries in legalising assisted suicide.

Of the nine lawyers on her list, not a single one is opposed to assisted suicide, despite numerous distinguished lawyers and former judges raising alarm bells about her Bill. Perhaps Leadbeater, who had to apologise for potentially misleading the House after she wrongly implied the judiciary was in favour of her Bill, did not want to be called out again by members of the legal profession. In total, according to MP Danny Kruger, of the names put before the committee, 38 were in favour of the Bill and the principle of assisted dying, while only 20 were opposed.

The committee will not hear from a single witness representing disability rights’ organisations, even though hundreds of them have raised concerns about the risk of coercion for disabled people. Not a single witness will speak about Canada’s disastrous ‘medical assistance in dying’ programme. Kit Malthouse, a committee member and one of the Bill’s co-sponsors, blithely dismissed Canada as irrelevant, even though British pro-assisted suicide organisations have been explicit about drawing their inspiration from the Canadian regime.

Most egregious of all, the pro-assisted suicide members of the committee, including both government ministers, voted down a proposal to hear oral evidence from the Royal College of Psychiatrists, which has expressed concerns about the Bill’s approach to mental capacity and coercion, because in Malthouse’s words, ‘it is not necessarily in the interests of time’ as the General Medical Council could represent the view of psychiatrists. Leadbeater later U-turned and allowed the College to testify: presumably she realised how contemptible it would be to exclude them.

The pro-assisted suicide majority on the committee voted to hold much of the session in private, which shielded their discussion from public scrutiny. Normally, a bill committee sits in private for a few minutes at the beginning of a session to discuss lines of questioning; on Tuesday the committee sat in private for more than an hour. We will never know what was said during this time, no record is kept.

It appears that Leadbeater has behaved since the Bill’s introduction as though her feelings override genuine concerns about the legislation. She behaved in the same petulant manner during the committee session, making aggressive points of order when she was challenged by other members. At one point, she angrily denied that the Bill had received significant input from pro-assisted suicide campaign groups, despite her close public association with the pro-assisted suicide group Dying in Dignity, which has made donations to her.

Jake Richards, another co-sponsor of the Bill,intervened only to describe two potential witnesses, a distinguished Chancery barrister and a Cambridge academic, as a ‘junior barrister’ and ‘junior lecturer’, while denying that he was ‘belittling’ them. Having called the witness list ‘objectively impressive and rigorous’, during the session it became apparent that he did not know who was on it, when he named two retired judges who were not on the list as witnesses.

The truth is that, to the Leadbeater Bill’s core supporters, the end justifies the means. After promising their colleagues that a vote at second reading meant further debate, Ms Leadbeater and her co-sponsors are trying to steamroll over their opponents. The many MPs who voted tor the Bill at second reading despite their reservations should watch the committee’s proceedings closely and ask themselves if they really want to associate their names permanently with this flawed legislation.

What the Russian spy ship exposed

Britain is heavily dependent on its underwater infrastructure. Ninety-nine per cent of our digital communications overseas are carried through subsea fibre optic cables.

Significant damage to them at the hands of malign actors would jeopardise our way of life. Defence Secretary John Healey reported to parliament on an incident last November when a Russian spy ship, Yantar, was detected ‘loitering over UK critical undersea infrastructure’ off Cornwall, a chokepoint for trans-Atlantic underwater communications. After the rapid deployment of ships, aircraft and submarines by Britain, Yantar took the hint to leave and is now, after a spell in the Mediterranean, on her war back home with the Royal Navy closely monitoring her movements.

Russian mischief is not new. The Soviet Union invested heavily in capabilities to sabotage Nato’s critical infrastructure (just as the UK cut the copper telegraph lines connecting Germany to the United States at the start of the first world war). That money also allowed the Soviets to map Nato’s critical undersea systems.

Putin has maintained Russia’s focus on the underwater. It today deploys a fleet of specialist submarines, naval ships and auxiliaries that use an array of sensors, manned and unmanned underwater vehicles. Yantar for example can send a crewed submersible down to below 20,000 feet.

The November incident was the latest of many over the last 20 years; Yantar has been a regular visitor to UK and Irish waters. In 2023, Ben Wallace the then defence secretary, pointed out that Russian submarines ‘in the North Atlantic and in the Irish Sea and in the North Sea [have been] doing some strange routes that they normally wouldn’t do’.

The Royal Navy is tasked with protecting critical undersea infrastructure. A new ocean surveillance ship, RFA Proteus, was used during the Yantar incident. The UK has also started an operation with its partners in the ten-nation Joint Expeditionary Force to track threats to undersea infrastructure, monitor the movements of the Russian shadow fleet suspected of damaging Baltic infrastructure, and issue real-time warnings of suspicious activity.

At the Nato Vilnius summit in 2023, the alliance established a new base on the outskirts of London for robust coordination, monitoring and countering of malign threats, and to deny any aggressor the cover of plausible deniability. Nato has also sent ships and aircraft to the Baltic.

The UK has a vital role in securing Europe’s maritime flank. In the Commons John Healey said that ‘those who might enter our waters with malign intent, or try to undertake any malign activity, know that we see them and know that they will face the strongest possible response’. For such a strong response to be credible will require sufficient ships, aircraft, and submarines ready to act. These have all been hollowed out over the last 30 years. The Strategic Defence Review is an obvious opportunity to ensure our vast, unseen, critical network of underwater infrastructure remains protected.

Labour U-turns on non-doms after millionaires flee

Well, well, well. It seems that Sir Keir Starmer’s Labour government is looking to row back on its non-dom rules after Britain suffered an exodus of millionaires after the introduction of the policy. Talk about a quick turnaround…

Speaking at a fringe event in Davos with the editor of the Wall Street Journal, Rachel Reeves announced the Labour government is planning to table an amendment to the Finance Bill. The Chancellor said that:

We have been listening to the concerns that have been raised by the non-dom community. The government amendment will increase the temporary repatriation facility, which enables non-doms to bring money instantly to the UK without paying significant taxes.

Trade Secretary Jonathan Reynolds backed up his colleague, remarking: ‘We welcome people coming to the UK and we’ll have a specific kind of tax treatment that they would expect.’ Similarly a Treasury insider told the Times: ‘We’re always interested in hearing ideas for making our tax regime more attractive to talented entrepreneurs and business leaders from around the world to help create jobs and wealth in the UK.’

The watering down announcement comes after figures revealed that the UK saw a net loss of 10,800 millionaires in 2024 – an increase of over 150 per cent on the previous year. The Adam Smith Institute suggests each of the millionaire moguls that left the country would have paid at least £390,000 in tax a year. Almost 80 millionaires deserted Britain last year, along with 12 billionaires, to countries like Italy and Switzerland – while financial advisers have warned that increasing numbers of British businesspeople are preparing to relocate after tax rises were announced in Labour’s Budget. Good heavens.

Will the Labour lot see the error of their ways on anything else? Watch this space…

Why are masked men shouting ‘down with India’ in cinemas?

On Sunday night a screening of the controversial Bollywood film Emergency was disrupted in Vue cinema in Harrow, West London, when a group of 30 masked men barged in and started shouting ‘down with India’. Most viewers left the screening, with one eyewitness describing the behaviour as a ‘frightening and intimidating experience’. Censorship of Emergency has extended to other parts of the country too, with screenings cancelled in places like Wolverhampton and Birmingham.

A video of the unruly behaviour Harrow shows the group shouting ‘Khalistan zindabad’, or ‘long live Khalistan’ (Khalistan is the would-be name for a conceptual Sikh homeland). A woman confronting the group responds with ‘Bharat Mata Ki Jai’ – which translates to ‘victory to Mother India’. This brief but illuminating exchange indicates the protestors are supporters of the pro-Khalistan movement, and the woman a pro-India patriot. But what is it about Emergency that has created tension and resulted in censorship?

For a start, the film has been directed (and starred in) by the right-leaning Bollywood actress-turned-politician Kangana Ranaut, of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). She doesn’t exactly have the best of records when it comes to public statements about Indian minorities. In 2021, her Twitter account was suspended for violating rules around hateful conduct and abusive behaviour with comments made about the West Bengal elections, when she urged Prime Minister Modi to resort to ‘gangster’ tactics to ‘tame’ the chief minister Mamata Banerjee, whose party had just defeated the BJP at the polls. The post included a veiled reference to the Gujrat massacre of 2002, when Modi was chief minister of the state. In 2020, a police complaint was also filed against Ranaut, for a video in which she referred to Muslims as ‘terrorists’.

More recently, Ranaut has got in trouble for her statements about Sikhs. In 2021, she made derogatory comments about protesting Sikh farmers on Instagram, resulting in a police complaint. She wrote on Twitter that Sikhs should ‘disassociate themselves from Khalistanis and come out in the support of Akhand Bharat’. Akhand Bharat, or ‘undivided India’, is a dreamt-up superstate promoted by right-wing Hindu nationalist groups like the BJP-linked Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), and includes Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh and Myanmar.

Emergency chronicles India’s dark history. Between 1975-77, the Indira Gandhi government imposed emergency rule for 21 months, following a Supreme Court order to stay a High Court decision, which declared Gandhi’s election to the Lok Sabha null and void. Civil liberties were suspended, thousands imprisoned (including the arrest of leading opposition politicians), the media censored, and 6.2 million Indian men from poor backgrounds were forcefully sterilised in just one year. The current Indian government has declared 25 June as ‘Constitution Murder Day’.

The Sikh protest at Emergency screenings, including in Harrow, is related to the unfavourable depiction of Sikh characters in the film, which is why Emergency was not released in Punjab – India’s only Sikh-majority state. The Sikh Press Association wrote: ‘The film is viewed as anti-Sikh Indian state propaganda for its depiction of ex-PM Indira Gandhi’s role in the Sikh genocide. She was the PM who initiated the Sikh genocide before her assassination by her Sikh bodyguards.’

I find Ranuat’s politics provocative and repugnant, but it’s wrong to censor her film, or any film for that matter. In fact, the worldwide release of Emergency coincides with the ongoing postponement of another Indian film, Punjab 95 – starring international superstar Diljit Dosanjh. So far, India’s Central Board of Film Certification has requested 120 cuts and forced the producers to change the film’s original name, ‘Ghalughara’ (which translates to ‘massacre’). It has been axed from film festivals too. Punjab 95 is about human rights activist Jaswant Singh Khalra, who exposed human rights violations and the mass cremations of thousands of Sikhs by Punjab police, in the period of insurgency following the 1984 Sikh massacres.

Those protesting with the aim to shut down screenings of Emergency across the UK are probably (like me) extremely frustrated with the seemingly endless censorship hurdles facing Punjab 95. It’s hypocritical to want Khalra’s story told, but to disrupt screenings that come from an opposing perspective. Cinemagoers should be free to watch both films and make up their own minds.

Can the Treasury get the public onside with its spending cuts?

As Rachel Reeves attempts to woo investors at Davos, the Chief Secretary to the Treasury has stayed behind in London as work gets underway on Labour’s comprehensive spending review. Darren Jones also found time to set out his thinking in a keynote speech at the Institute for Government’s 2025 conference, where he laid out stricter funding requirements for government departments and plans for Treasury reform in a bid to impose tighter controls over spending.

Jones batted off attempts to pin him down on government controversies playing out elsewhere – using, as Keir Starmer did in PMQs on Wednesday, the ‘speculation’ excuse to avoid commenting on plans to install a third runway at Heathrow Airport, a move that he had previously labelled ‘unconscionable’. Sticking to the script, he was clear that if government departments don’t meet the Treasury’s requested 5 per cent spending cut they won’t receive money for new projects. ‘We are long overdue a reckoning with government spending,’ Jones said firmly. ‘We will no longer just negotiate what top ups to existing projects departments will get, but we will scrutinise and challenge every pound of existing budgets first.’

Yet despite his thinly-veiled warnings about tough cuts ahead, Jones was upbeat as he described his plans for Exchequer reform. From digital dashboards featuring modelling systems that will predict policy benefits to using AI to analyse departmental spending, Jones was keen to stress that the tech revolution is coming to the Treasury. Departments will be brought together in ‘mission groups’ to help better divvy up funds and make spending a ‘shared problem’, ensuring too that money spent is more specifically directed to Labour’s ‘plan for change’ priorities. Meanwhile further scrutiny of spending plans will come via ‘challenge panels’ of academics and experts.

Jones wants to put data ‘at the heart’ of the spending review to better understand how departments can work together to drive growth. The idea is to be able to have a system that continuously evaluates how effective government spending is. The Reeves-founded Office for Value for Money will play a key role, and Jones was keen to highlight that the Treasury has accepted the first recommendation from the quango to set up regular ‘value for money reviews’ in the alternating years between spending reviews. The announcement comes amid reports some MPs aren’t convinced it itself is value for money – and it will take more than that to convince the Treasury select committee of its worth. Committee chair Dame Meg Hillier remarked this week that the organisation was ‘understaffed, poorly defined [and had been] set up with a vague remit and no clear plan to measure its effectiveness’. Hillier is also a Labour MP.

Will more transparency really manage to soften the blow of ‘ruthless’ spending cuts?

If the government’s internal reform pans out the way Jones hopes, by the time the next election comes around ‘the way you engage with the state should feel very, very different’. However Jones wants to first engage with Brits on the spending review. ‘One group that I’m amazed we don’t engage more often in these types of issues is the public,’ he told the IfG audience. ‘When spending reviews happen, the public are not involved in any way.’ Announcing with some enthusiasm that he was being ‘allowed out of the Treasury to go around the country’, Jones is planning to engage more with public service users and workers to ‘just provide a little bit of challenge and depth and colour about the decisions we take with our dashboards and our spreadsheets in the nice offices in Whitehall’.

And that is the crux of the matter: as well as getting colleagues on side, the Treasury man needs public support if he wants to see his reforms take place sans hitch. Despite Labour wasting no opportunity to highlight the challenges facing the new government and the party’s call for patience, both Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s ratings and those of the government have steadily worsened over the last six months while even Labour’s own supporters have been quick to turn their backs on the reds. Jones’s hope is that re-evaluating how the government speaks to voters and being more up-front about hard decisions will help tame the public response.

But will more transparency really soften the blow of ‘ruthless’ spending cuts – as opponents will surely be quick to slam ‘austerity measures’ and warn of tax rises? After all, the spending review could see unprotected departments having to find difficult savings. Things could get even worse if Reeves finds in March that the OBR forecasts are unforgiving – and she may have to find fresh cuts or raise taxes to meet her fiscal rules. While the cost-of-living crisis and state of public services remain top priorities for Brits, it’s going to take a lot of talking to keep them on side.

Listen to more on Coffee House Shots, The Spectator’s daily politics podcast:

The reinvention of Rishi Sunak

Rishi Sunak (remember him?) is back in the public eye. The former prime minister has landed new jobs at Oxford and Stanford universities. The roles are his first since returning to the backbenches last year following the crushing Tory defeat at the general election in July.

His time in Downing Street doesn’t look as bad as it once did

Sunak is joining Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government as a member of its world leaders circle. He will also be taking up a visiting fellowship at Stanford’s Hoover Institution in California. Both universities are Sunak’s alma maters. He studied politics, philosophy and economics at Oxford before completing a masters of business administration degree at Stanford. Sunak met his future wife Akshata Murty, the daughter of an Indian billionaire, while studying at Stanford. Sunak said he was “delighted” to be joining the two institutions, adding: “Both Blavatnik and Hoover do superb work on how we can rise to the economic and security challenges we face and seize the technological opportunities of our time.”

Sunak has always had his admirers in politics and beyond, people who see in him something that somehow escaped the majority of voters at the recent election and for much of his short tenure in Downing Street. Lord Hague, a former Tory leader who is now chancellor of Oxford University, is firmly in the Sunak camp. He said the former prime minister’s experience and “deep understanding of the challenges facing governments today “would be “a huge asset”. Sunak may well have a deep understanding of such matters, but it would be a stretch to suggest that he had the foggiest when it came to finding actual solutions.

Another Sunak fan is Condoleezza Rice, the former US Secretary of State and director of the Hoover Institution. She said the former prime minister’s “extensive policy and global experience will enrich our fellowship and help to define important policies moving forward”, adding that she looked forward to “the impact of his work on the many challenges facing democracies and the world to come.” Perhaps Rice isn’t aware that Sunak is planning to stay on as the Tory MP for Richmond and Northallerton, in North Yorkshire. How will he find the time?

Sunak was eager to share his good news about Oxford and Stanford on Instagram, where he posted a photograph of himself and Akshata from their student days, writing: “These two incredible institutions shaped the person I am today”.

It is a form of words that prompts the obvious question: Who exactly is Sunak? What is this authentic self that he refers to? He remains something of an enigma, a politician who ascended to the summit of politics almost without trace.

Sunak became prime minister unexpectedly in October 2022 following the short-lived and financially disastrous premiership of Liz Truss. At the age of 42, he was the youngest leader of the country in more than two centuries. He inherited a difficult hand in Downing Street but played it poorly. His 20 months in office consisted of grappling with a series of crises. He had enough grasp of the policy issues, but came across as hapless at the politics – a rather curious observation to make of someone who reached the very pinnacle of power, but true enough. Looking back, there is no discernible ideology that might be described as “Sunakism” – the most that can be said of his political ideas is that he clung to some form of economic Thatcherism, was pro-Brexit, and unconvincingly boosterish on the benefits to the economy of AI.

He had no real answer to Britain’s problems and his political judgment left a lot to be desired. His decision to hold the general election in July last year surprised everyone, friend and foe. Sunak made the announcement in pouring rain outside Number 10, his voice drowned out by the Labour anthem “Things Can Only Get Better”. The campaign was an unmitigated disaster. The highlights reel of unforced errors by Sunak includes his decision to leave the D-Day commemorations in Normandy a day early to do a TV interview. In short, Sunak as prime minister was no stranger to political self-harm.

Even so, the announcement of his two new university roles marks the official beginning of Sunak’s attempts to forge a post-prime ministerial career. He has had time aplenty to lick his wounds after the fiasco at the polls. He might even be permitted a wry smile at the thought that his warning to voters that electing a Labour government risked economic disaster appears more prescient by the day. Sunak may not have been up to the top job, but his time in Downing Street doesn’t look as bad as it once did. He has the new Labour government to thank for that.

Elon Musk’s ‘Nazi salute’ – an expert’s view

As a biographer of the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini and thus possessed of a certain expertise in the matter I want to add my thoughts about Elon Musk’s bizarre raised right arm salute.

Many on the left, including historians who ought to know better, say that the gesture delivered with such passion at the rally in Washington for the party faithful after Trump’s inauguration was a fascist or Nazi salute.

If Musk had made such a gesture in front of the Duce, he would have been instantly banished to the beautiful Tremiti Islands off the coast of Puglia along with the gays

But not just on the left. Even alt-right Steve Bannon’s Rome-based international editor Ben Harnwell – like his boss a sworn enemy of all things left-wing – has joined the howls of protest in unholy alliance.

Bannon was the architect of Trump’s 2016 presidential victory but is now in exile, with a popular podcast, The War Room. He has declared Musk his enemy above all, maybe because the tech multi-billionaire wants to import lots of skilled migrant workers.

Well, be that as it may, whatever Musk did on Monday evening on stage in the Capitol One Arena, it was most definitely not a fascist or a Nazi salute, or to give it its correct title, a Roman salute.

A proper Roman salute involves standing dead still and raising the right arm, from the resting position next to the right hip, straight out in front, up to an angle of 45 degrees, with the palm of the hand facing down, fingers touching and outstretched.

It was the poet warrior Gabriele D’Annunzio, often called the first Duce, who made the Roman salute popular when in 1919 he led a force of volunteers to capture the port city of Fiume (now Rijeka in Croatia).

The fascists who seized power in 1922 soon made it their own. They said, without much evidence, it had its origins in Imperial Rome from which they took much of their inspiration. It was later copied by the Nazis.

However weird it may seem to us today, fascism was an alternative left-wing revolutionary movement to Communism invented by the revolutionary Socialist Mussolini to replace international with national Socialism.

This explains the Roman salute. Mussolini insisted that it replace the handshake as the standard form of greeting on the grounds that the handshake was bourgeois and unhygienic. The handshake reeked of what he called ‘pipe and slippers unproductive parasites’. Yes, indeed, the bourgeoisie was the fascist class enemy just as it was for the Communists. Who’d have thought it when today fascism is called far right?

The fascist version of the Roman salute involved raising the right arm higher than in the Nazi version. The Nazis also added a techno Teutonic twist: once the arm was raised to the correct angle the palm of the hand would be pivoted down.

During the Covid crisis I wondered if the Roman salute might make a come-back in Italy but instead the Italians opted for touching elbows.

Let us try to be honest. The arm gesture delivered by Musk during his three and a half minute speech was more like a Star Wars style version of a high-five.

His right hand began placed across his heart and from there shot out, yes, upwards but more or less sideways, not in front. He then repeated exactly the same gesture to the crowd behind him on the stage. Nor was he ever standing still as required but gyrating.

The gesture done, he then placed his right hand back across his heart and told the crowd: ‘My heart goes out to you. It is thanks to you that the future of civilisation is assured.’

Obviously, he was using his right arm like an arrow or a spear that came from his heart and would reach the stars.

If Musk had made such a gesture in front of the Duce, he would have been instantly banished to the beautiful Tremiti Islands off the coast of Puglia along with the gays. If he had done it in front of the Fuhrer, he would have been deported somewhere far worse.

Few know this but in America in the first half of the 20th Century a salute very similar to the Roman salute – known as the Bellamy salute – was widely used when taking the oath of allegiance which Americans do all the time. This meant – as the instructions to schools explained that ‘every pupil gives the flag the military salute – right hand lifted, palm downward, to align with the forehead and close to it.’

The lower angle of the arm made the salute closer to the Nazi rather than the fascist version. There was though a key, rather touching, difference. When the oath of allegiance was completed ‘the right hand is extended gracefully, palm upward, toward the Flag, and remains in this gesture till the end of the affirmation; whereupon all hands immediately drop to the side.’

In 1942, Congress then passed a law clarifying that the straight-arm salute during the oath of allegiance ‘be rendered by standing with the right hand over the heart; extending the right hand, palm upward, toward the flag at the words “to the flag” and holding this position until the end, when the hand drops to the side.’

That surely is much closer to what Musk did. Only later did Congress ban the straight arm salute and insist that the oath be sworn with the right hand over the heart alone.

Regardless of all this, the left, with little else left to talk about, swung into action. Ruth Ben-Ghiat, professor of history and Italian studies at New York University, wrote on social media: ‘Historian of fascism here. It was a Nazi salute and a very belligerent one too.’

Oh no it wasn’t.

And here is Italy’s ever more insufferable left-wing cultural supremo, Roberto Saviano, author of the book about the Neapolitan Mafia, Gomorrah: ‘May you be cursed. The end of all this will be violent. His (Musk’s) fall will be equal to that of those to whom it historically refers with this gesture.’

But it’s not just the left.

It is also Bannon which means many of Trump’s MAGA base of so-called ‘deplorables’. Bannon is at daggers drawn with Musk. He told the Corriere della Sera earlier this month: ‘He is a truly evil guy, a very bad guy, I made it my personal thing to take this guy down.’

Harnwell, Bannon’s man in Rome, posted a vitriolic tweet on the social media platform Gettr about what he called Musk’s ‘quick little Sieg Heil’ in which he said:

‘The guy is too much of a techno-nurd to be a neo-Nazi. If ever you hear him speak without notes, he can’t rise above third-rate platitudes — he has no political thought. He’s not well-read enough to be of those feverish white-supremacist marshes. No. He thinks that’s who you are. Never forget he did call you all racist retards during his H-1B (skilled worker) visa meltdown. He thinks by flashing you a fascist salute he will win you all over. That’s how little this opportunistic grifter understands MAGA.’

Musk often gives me the impression that he is like a child unable to control his emotions. He is, it is said, autistic. I think it is this that’s behind his gesture. I do not think he is a fascist.

However, I do find it tricky to understand how such a brilliant mind could fail to see the inevitable reaction that such a gesture would provoke. Unless he wanted such a response. And why would that be? Simply to taunt the left?

He posted on X: ‘Frankly, they need better dirty tricks. The “everyone is Hitler” attack is sooo tired.’ But that’s not really much of an answer is it?

Germans no longer feel safe after these horrific crimes

In a knife attack in the Bavarian town of Aschaffenburg, a two-year-old boy and a 41-year-old man were killed in a park on Wednesday. Three more people were injured, among them two-year-old girl. A suspect has been arrested and identified as an Afghan national with a history of violence and psychiatric issues.

The horrific details of the incident were released by police and the Bavarian Minister of the Interior Joachim Herrmann shortly after and caused widespread outrage. The 28-year-old suspect reportedly targeted a particular boy, who was in the park with other children from his kindergarten group. He walked up to him and stabbed him to death with a kitchen knife. A bystander intervened and was also killed.

The suspect then stabbed a small girl in the neck three times before attacking another 72-year-old man. A kindergarten teacher broke her arm as she tried to flee. The injured victims were taken to hospital and don’t appear to be in critical condition. Other bystanders and police chased down the perpetrator. He was arrested and taken into custody.

Germany’s mainstream parties will be worried that the anger, frustration and fear triggered by this attack will fan the flames of the Alternative fur Deutschland

The local public reacted with deep shock. ‘I’m just frightened because this could have been us,’ one young woman told the German news outlet Die Welt, adding: ‘we’re afraid to walk down the street.’ Another woman said, ‘this kind of thing does something to you…when you leave the house now you feel unsafe.’

German politicians appeared visibly shaken by the incident. Economics Minister and Vice Chancellor Robert Habeck said ‘terrible isn’t strong enough a word. From what I’ve read so far this couldn’t have been more brutal and perverse.’ The Bavarian Minister President Markus Soder called it a ‘vile deed’.

Fellow Bavarian politician Klaus Holetschek went even further, saying that while he was sad and full of empathy for the victims, his main emotion was ‘anger’. ‘At the end of the day,’ he said, ‘the state must fully protect its citizens – there must not be any more misguided tolerance.’

The incident came just a month after the Christmas market attack in Magdeburg in which six people were killed and at least 299 wounded when a car ploughed into the crowds at high speed. The driver was arrested on the scene and identified as Taleb al-Abdulmohsen, who came to Germany from Saudi Arabia in 2006 and was known to the authorities for making terrorist threats.

The two attacks are not directly related, but they fall into a recent spate of incidents in which the suspects had claimed asylum in Germany and had then gone on to commit serious acts of violence. What many Germans will take from this is that the authorities were unable to stop any of the men from killing, injuring and terrorising innocent people, including children.

Even Chancellor Olaf Scholz issued a sharply-worded statement that went much further than the usual expressions of empathy and promises to investigate the incident and punish the perpetrator. ‘That isn’t enough,’ he wrote, adding that he was ‘fed up with such brutal acts occurring every few weeks in our country – committed by perpetrators who had originally come to us to seek protection. In light of this, misguided tolerance is completely inadequate. The authorities must investigate promptly why the assassin was still in Germany in the first place. From those findings consequences must follow – talk is not enough.’

Scholz’s opponent Friedrich Merz, the man most likely to become the German chancellor following the snap elections on 23 February also demanded action: ‘It can’t go on like this. We must restore law and order.’

Germany’s mainstream parties will be worried that the anger, frustration and fear triggered by this most recent attack will fan the flames of Alternative fur Deutschland (AfD) whose core issue is immigration. They are currently polling in second place on around a fifth of the vote, and have recently sharpened their manifesto further, embracing the idea of mass deportations of foreigners from Germany under the term ‘remigration’, which the party had previously dropped.

Responding to the Aschaffenburg attack, AfD leader Alice Weidel immediately took to Twitter to point out that the incident happened in Bavaria, which is run by the conservative CSU. The CSU has also promised tighter rules on immigration should it come into power together with its sister party, Merz’s CDU.

Weidel has argued for some time that the conservatives may talk tough on immigration but won’t do enough on it. Indicating that her party would go much further than border closures and deport people already in the country, she responded to the Aschaffenburg attack with the demand: ‘Remigration now!’

These brutal murders will have political consequences. Germany’s mainstream parties are beginning to recognise that an increasing number of Germans no longer feel safe, and that they expect politicians to take their concerns seriously. Whether they can win back trust fast enough with only weeks to go until the elections remains to be seen.

What is already clear, however, is that many voters want to see genuine change in the areas of public safety and immigration regardless of who wins the election. If the mainstream parties manage to form another coalition and keep the AfD out of power, as looks currently likely, they will have to work together on these issues, and fast, or else the next election may produce a very different result.

Calin Georgescu has exposed the rotten European Union

To the great surprise of very few the European Court of Human Rights this week rejected an appeal by Calin Georgescu to overturn last month’s annulment of Romania’s presidential election. The Eurosceptic Georgescu had won the first round of November’s election, but days before the second round Romania’s Constitutional Court cancelled the result because of alleged Russian interference on social media. In its decision, the ECHR said that Georgescu’s appeal fell outside its jurisdiction.

That was the bad news for Georgescu. The good news was the publication of a poll this week that puts him firmly in front to win the election when it is re-run in May. He is forecast to take 38 per cent of the vote in the first round and then defeat his nearest rival, Crin Antonescu, in the second round to become president.

Europe’s elites seem to have no scruples with thwarting those with ‘wrong’ opinions from taking power

Antonescu has been selected as the candidate of the ruling coalition, that coalition being comprised of three pro-EU parties: the Social Democrats, the Liberals and the UDMR, which represents the Hungarian minority in Romania.

It would be a stretch to call Antonescu an inspired choice. A jobless history professor who has been out of political life for a decade, the 65-year-old Antonescu struggled to make his mark even when he was in his prime. From 2009 to 2014, he led the National Liberal Party and he was, for 48 days in 2012, the interim president of Romania after the suspension by parliament of Traian Basescu – a process initiated by Antonescu. Basescu challenged the ban and was quickly reinstated.

In a profile in 2014, Politico said Antonescu had ‘emerged a loser, with his image tarnished’. It described his rhetoric as ‘wild and shrill’ and his character as ‘confrontational and emotional’. Evidently, the Romanian electorate shared that view, and Antonescu’s ambition to run for the 2014 presidency was terminated when his Liberal party performed poorly at that year’s European elections and he resigned.

Thus ended Antonescu’s political career… or so he and Romania thought. Now he may finally fulfil his ambition to become president.

The polls suggest that Antonescu stands little chance of beating Georgescu, but he would if his rival was disqualified. That might happen. Speculation is growing that the Constitutional Court will intervene again, this time banning Georgescu from running ‘because of accusations of undeclared funding’.

It wouldn’t be the first time. In October, the nine-strong court invalidated the candidacy of Diana Sosoaca, the leader of SOS Romania, described as ‘a small ultra-nationalist Eurosceptic party’, which had won two seats in the European elections last June. The Court ruled that Diana Sosoaca was disqualified from running for president because she was incapable of respecting the country’s constitution and would threaten Romania’s membership of Nato and the EU.

‘This proves the Americans, Jews and the European Union have plotted to rig the Romanian election before it has begun,’ said Sosoaca by way of response.

The decision to exclude Sosoaca was criticised by her political rivals, who expressed concern that a dangerous precedent had been set. The centrist MEP Eugen Tomac declared that while he abhorred Sosoaca’s views ‘this kind of reckless politician should not be stopped using Putin-style methods’. Rather, he said, the democratic process should be allowed to run its course at the voting booth.

These actions by the Romania’s courts have reinforced the view among some Romanians – and shared by many millions across the EU – that Europe’s elites have no scruples with thwarting those with ‘wrong’ opinions from taking power. Look at the results in recent elections in Spain, Holland and France, where all of the winners were kept out of office by cobbled-together coalitions.

Earlier this month, Radu Magdin, a Romanian political analyst, said that what happened to Georgescu had harmed the country’s image in the eyes of the world: ‘In order to regain our clout as a serious country, we need a serious inquiry into what happened.’

At a speech at Davos on Tuesday, the EU Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, touched on what Donald Trump’s ‘Golden Age’ might mean for Europe. ‘We will be pragmatic, but we will always stand by our principles,’ she declared. ‘To protect our interests and uphold our values – that is the European way’.

Does protecting the EU’s interests and values extend to turning a blind eye to electoral interference by politically-appointed courts in member states? If it does, then the EU, like Romania, doesn’t deserve to be taken seriously.

There’s only one way to end the war in Ukraine

Donald Trump has told Vladimir Putin to end the war in Ukraine. ‘Settle now, and STOP this ridiculous war!’ he wrote on Truth Social yesterday. ‘IT’S ONLY GOING TO GET WORSE.’ But if the new president wants the war in Ukraine to end, American diplomats may have to open talks with Russia on issues much wider than Ukraine. Russia’s problem, after all, is not just with Ukraine, but with the West. Is there a deal that will make Russia, Ukraine, the US, Europe and the rest of the world, happy?

Russia went to war to prevent Ukraine joining Nato and to regain for Russia a say in European security issues, and Donald Trump made it clear in a meeting with French President Emmanuel Macron that his administration will not support Nato membership for Ukraine. Moreover, the fact that the Biden administration and every other Nato government has publicly ruled out going to war for Ukraine makes the idea of a Nato Article 5 guarantee prima facie empty.

Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov recently explained where he thinks a post-war Ukraine should fit within Europe’s security architecture. He said that Russia ‘recognised the sovereignty of Ukraine back in 1991, on the basis of the Declaration of Independence, which Ukraine adopted when it withdrew from the Soviet Union.’

Another option that has been discussed is the so-called ‘Israeli model’

Lavrov added: ‘one of the main points for [Russia] in the declaration was that Ukraine would be a non-bloc, non-alliance country; it would not join any military alliances… on those conditions, we support Ukraine’s territorial integrity.’ Until 2014, neutrality was indeed part of Ukraine’s constitution – although governments in Kyiv had already violated this by seeking Nato membership.

One alternative to formal Nato membership – in fact, to membership of any military alliance – would be having a large, well-armed ‘peacekeeping’ force provided by European countries and based in Ukraine. This has been discussed recently. In December, officials from Nato, the EU, the UK, France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Ukraine met to discuss possible security guarantees for Ukraine, including this. Officials familiar with the talks say that ‘any European troops on the ground would be part of a specific peacekeeping or ceasefire monitoring force and wouldn’t be a Nato operation.’ In practice though, this would be a Nato operation in all but name, since all the contributing states would come from Nato. The Russian government has therefore made clear that they will reject this idea. Zelensky probably didn’t help by saying that the peacekeeping force would require at least 200,000 soldiers to be massed near Ukraine’s border with Russia – more than the entire deployable armies of Britain, France and Germany put together.

Although the Trump administration is considering this idea, it will also certainly in the end reject it. For as the Wall Street Journal has reported, ‘French officials have made clear that the idea would need to involve some kind of US backup.’ According to the Financial Times, officials familiar with the December talks on security options have said that ‘binding security guarantees from European capitals that would potentially involve them in a war with Russia if Ukraine was attacked again are unfeasible without a guarantee that the US would support those European armies.’

The Trump administration will never give such a guarantee – nor should it, since in the event of a new war this would leave the US with the choice between utter humiliation and direct war with Russia, involving a severe risk of nuclear annihilation.

Key European states have already ruled out participation in such a force – unless the Russians agree to it, which they will not do. When Macron discussed the European peacekeeping option with Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk, despite being one of Ukraine’s strongest allies, Poland spurned Macron. Tusk replied: ‘To cut off speculation about the potential presence of this or that country in Ukraine after reaching a ceasefire… decisions concerning Poland will be made in Warsaw and only in Warsaw. At the moment we’re not planning such activities.’

The leader of the German Christian Democratic Union (and probable Chancellor after the elections due in February), Friedrich Merz, called talk at this time of German troops being part of such a force ‘irresponsible.’ He said: ‘If a peace agreement is reached and Ukraine needs security guarantees, we can only discuss this if there is a clear mandate under international law. I don’t see it at the moment. I would like such a mandate to be given in consensus with Russia, not in conflict.’

Another option that has been discussed is the so-called ‘Israeli model’, or heavily-armed neutrality – for Israel, although armed and strongly supported by the US and other western countries, is not a US or Nato ally. This might be acceptable to Russia if the weapons supplied to the West were defensive (ruling out for example long-range missiles and advanced fighter jets), but in Russia, Ukraine is facing a vastly more formidable adversary than any that Israel has ever faced.

One partial answer to this difficult situation is to get the United Nations and the international community as a whole to endorse the peace settlement. While the great majority of countries have refused to join western sanctions against Russia, they also did not want this war and would not want it to resume. Since Moscow has made reaching out to what it calls the ‘global majority’ a central part of its diplomatic strategy, it would be very unwilling to alienate them by starting a new war.

In the end however, the only truly strong guarantee of peace in Ukraine and between Russia and the West will be a new security architecture that over time reduces fear and distrust between them. This was the great chance offered by the end of the Cold War, which (due to faults on both sides) was tragically lost. Russia proposed a treaty along these lines to the US two months before launching the invasion of Ukraine. Some of its provisions were clearly unacceptable, but others made good sense. Yet the Biden administration refused to discuss it at all.

This would not be an absolute and permanent guarantee of Ukrainian security – but then, in history there is no such thing as a permanent guarantee. As long as Russia exists, so will the possibility of Russian aggression against Ukraine; and as long as the US exists, there will be the possibility of a future US administration launching a new anti-Russian crusade.

We cannot tell what the world will look like generations from now. There may be some kind of global disaster that renders our present security concerns irrelevant. But as the great Gandalf says in the Lord of the Rings: ‘It is not our part to master all the tides of the world, but to do what is in us for the succour of those years wherein we are set.’

Britain is losing friends – and making enemies

Whatever way you voted in 2016, I suspect that many of us have the same image of post-Brexit Britain. It is easier to capture in a cartoon than in prose but it looks something like this. A chap tries to make a leap across a canyon, falls ever so slightly short and as a result gets wedged in a crevice. And there he is – stuck. Neither on one side or the other and gaining the benefits of neither ledge.

The Conservative party obviously carries a large amount of responsibility for this – not least for the fact that European law still dictates our insane migration policy. But the current government must also take its share of responsibility. If we were run by competent men and women of vision then getting out of the spot we are in could be possible. Instead it appears that Labour policy is to actually push us further down the crevice.

On issue after issue Britain is in this same netherworld

Because of the Labour party’s obvious attraction to the EU, they will not take this country an inch further away from it. Keir Starmer and his party have already signalled that if a trade war were to erupt between the US and the EU, then the UK would side with the EU. But at the same time, Britain has never been more unlike our European friends. Right-wing politics dominates the continent and is only rising. And it’s not just ‘right-wing politics’ as it might be defined by any remaining producer at Newsnight, but proper right-wing stuff of a kind that even causes me to make a whistling noise at times.

Geert Wilders is now the head of the largest party in the Dutch parliament. This is a man who was idiotically refused entry into the UK by a Labour home secretary (the hopeless Jacqui Smith) because of his ‘divisive’ and ‘extreme’ views. Not so long ago Giorgia Meloni was endlessly described as ‘fascist’ and ‘far-right’. Today, as Italian Prime Minister, she is recognised as one of the more moderate leaders in the EU bloc.

And here is where our current government has managed to play an absolute political blinder. Because while we’ve never been further away from the Europeans, the geniuses in charge seem to have decided to make sure that the American government doesn’t like us either.

You don’t have to resort to the extreme case of Sadiq Khan, but let’s. This is a man who chose to spend his time over inauguration weekend warning, originally enough, that Donald Trump’s return to the White House spells the return of ‘fascism’. On inauguration day he posted a picture on X of himself standing in front of a billboard in Piccadilly Circus that boasted the slogan ‘London is, and will always be, a place for everyone ♥’.

This message was obviously meant to stand in stark contrast to the terrible extremism that has broken out in the US. Although if Khan were capable of looking locally, rather than attempting to cast his gaze abroad, he might see that London being ‘for everyone’ is a large part of its problem. Many Londoners feel that London ought not to be a place for machete gangs and knife murderers, phone-robbers and bicycle stealers, rape gangs and anti-British lunatics. But that’s a matter of personal preference, I suppose.

On almost every major issue Britain is now a country that is failing to tack itself to anyone on the world stage while also lacking a viable long-term view on almost anything. This week, Mayor Khan also announced that he intends to launch a legal challenge if the Prime Minister backs a third runway for Heathrow airport. This is the sort of thing that signals a country in a serious stalemate, not to mention decline. After all, you can either decide to grow outside investment or you can decide to throw your lot in with people like Ed Miliband, who never saw an investment opportunity they didn’t wish to demolish.

Which brings me to another matter: the idiotic decision of successive post-2016 governments to get everything wrong in new ways. One of the reasons Boris Johnson’s government wasted what little time it had was that it sucked so hard on the net-zero bong and presumed to ‘lead by example’. This Labour government is likewise full of people who think that Britain should immiserate its economy and energy policy by ‘leading the world’ into anti-fossil fuel ultimatums. The fact that the Chinese Communist party is busily building coal-fired power stations and nuclear power plants might suggest to you – as it does to me – that the CCP is not much looking to Miliband. If they ever do think of him I imagine they think him rather silly and presumptuous.

Johnson’s only excuse for mainlining this nonsense was that he wanted to demonstrate to Joe Biden that he wasn’t Trump. But now Johnson and Biden could not be further from power and we have a US President who has promised in his first speech in office to ‘drill, baby, drill’. Once again the energy policies of Johnson and Miliband look more like the debunked ideas of yesterday’s men than a case of leading by example.

On issue after issue Britain is in this same netherworld. Our government has no idea how to grow the economy, is trying to tax its way to growth, is busy chasing out the rich and making the ambitious scram. Having one side of Britain stuck against the European side of the cliff, we have a government with no apparent desire to clamber out of the ravine on to the booming American side. Instead our politicians preen and fall back on student slogans and banalities so past their sell-by date that they would shame the discount shelf at the Co-op.

There was a time when one of the great slogans in our country’s history was ‘Very well, alone’. Whether on immigration, crime, the economy, energy or foreign policy, we are now in that strange position again. But not in a good way. Not in a good way at all.

Watch more from Douglas Murray on Spectator TV:

Seneca’s guide to coping with disaster

How does one attempt to console someone on the destruction of their home, a fate recently visited on so many citizens of Los Angeles? Seneca, the millionaire philosopher and adviser to the emperor Nero, associated consolation with ‘reprimanding, dissuading, exhorting, commending’. He exemplifies that in a letter musing on the reaction which his friend Liberalis had had to the destruction by fire of his beloved Lugdunum (Lyon) in Gaul ad 64. This had caused Liberalis to worry about the strength of his own character, usually so steadfast, when confronted with this disaster.

Seneca contended that we should be ready for anything, since there is ‘nothing that Fortune, when it so wishes, does not topple at the height of its prosperity’. War arises in the middle of peace, friends become foes. There would be some consolation if all things perished as slowly as they came into being, but ruin is rapid. Nothing, whether public or private, is stable; the destinies of men no less than of cities are tossed about.

We must therefore confront the operations of Fortune. What man builds up will fall to the ground; mountains collapse, and seas overwhelm the land. Cities stand, but to fall. ‘It would be tedious to recount all the ways by which fate may come, but this one thing I know: all the works of mortal man have been doomed to mortality and in the midst of things which have been destined to die, we live.’

So we must not cry out at these calamities. Into such a world have we come and under such laws do we live. We will grow old, we will be sick, we will suffer loss, and we will die. None of these is a burden which it is impossible to bear; it is only common opinion that makes it so. ‘Your fearing of death is like your fearing of gossip: and what is more stupid than a man who fears words? In fact, nothing has power over us, when we have death in our power.’

All this is well in line with the ancient view that reaction to success and disaster alike is a matter of character, formed by education and self-control (Plutarch), which will, of course, make you a man, my son. Discuss.

The Pope’s revenge: why the new Archbishop of Washington is such a controversial choice

For an 88-year-old man who has spent only five days in the United States and doesn’t speak English, Pope Francis is a surprisingly partisan observer of American politics. For most of his life he was, like a typical Argentinian, viscerally but vaguely anti-American.

Robert McElroy’s nickname among Catholic conservatives is ‘the wicked witch of the west’

But by the time he became Pope in 2013 both he and the Democratic party had embraced the ideology of the globalist left. And so they became allies. In 2016, Francis gave his blessing to the Hillary Clinton campaign’s Catholic front organisations, motivated not just by a shared obsession with anti-racism and climate change but contempt for Donald Trump.

On 20 January 2021, just before Joe Biden was sworn in as America’s second Catholic president, the Pope publicly undermined Archbishop José Gomez of Los Angeles, who as president of the US bishops’ conference had drafted a statement praising Biden’s piety and social conscience but deploring his hardline support for abortion. The bishops’ statement was reportedly spiked until after the ceremony on the orders of the Vatican.

Naturally the Pope is horrified to find Trump back in the Oval Office. This time, however, the Vatican didn’t try to harvest votes for his opponent. There was little point, given Kamala Harris’s history of baiting Catholic judges, her embrace of gender ideology and her decision to boycott the Al Smith dinner, the major charity event in the US Catholic Church’s calendar. In November Trump extended his lead among Catholics from five points in 2020 to 15.

But if Francis could do nothing to stop increasingly conservative US Catholics from supporting his arch-enemy, he could at least punish them. On 7 January he announced that Cardinal Wilton Gregory, the retiring Archbishop of Washington, would be succeeded by Cardinal Robert McElroy, the current Bishop of San Diego.

This Pope is one of the most relentless score-settlers in the history of the papacy. It’s a character trait he shares with the 45th and 47th President of the United States – an unpleasant one, to be sure, though sometimes it’s hard to keep a straight face at the sight of such old men taunting their enemies like schoolboys.

Making McElroy the archbishop of the nation’s capital, however, is more than an act of petty revenge. No one in the American Church has benefited more from Francis’s vengefulness than McElroy, who will be 71 when he moves to Washington in March. He has been the Bishop of San Diego, a suffragan see of the metropolitan archdiocese of Los Angeles, since 2015. Unlike José Gomez, therefore, he does not have the title of archbishop.

There’s nothing unusual about a pope promoting a middle-ranking bishop to a major see such as Washington (which has no ‘DC’ in its title because it spills into neighbouring states). The oddity is that since 2022 Bishop McElroy, who ministers to 1.3 million Catholics, has been a cardinal, while his boss, the Mexican-born Archbishop Gomez, shepherd of 4.3 million Catholics, has failed to receive a red hat in any of Francis’s ten consistories. As a result – incredibly – the Catholic Church in the United States has still to acquire its first Hispanic cardinal.

The elevation of McElroy shows Francis at his most authoritarian. McElroy is the most left-wing member of the US hierarchy. His nickname among Catholic conservatives is ‘the wicked witch of the west’. He detests Trump, opposes immigration reform, supports women’s ordination, cancels Latin masses and opposes ‘dividing the LGBT community into those who refrain from sexual activity and those who do not’. He also thinks the Church focuses too much on abortion. He is, however, careful to express his opinions in the dad-dancing jargon of ‘synodality’ adopted by ambitious clerics under Francis. Amusingly, he claims that Harvard taught him to write with ‘greater clarity and elegance’. One shudders to think what his prose was like beforehand: his recent lectures on ‘radical inclusion’ remind one of Mark Twain’s description of the Book of Mormon, ‘chloroform in print’.

Although McElroy has always been conspicuously pro-Francis, he nearly didn’t get the Washington job. According to the Pillar, an American Catholic news website to which high-ranking clerics in Rome leak stories, the Pope decided against appointing McElroy after his nuncio to the United States, Cardinal Christophe Pierre, advised him that he would be too ‘polarising’.

But last month, Trump announced that he had selected Brian Burch, founder of the uncompromisingly pro-life (and pro-MAGA) organisation CatholicVote, to be his ambassador to the Holy See – at which point Francis made the tit-for-tat appointment of McElroy to Washington.

Non-Catholics understandably feel that the Church, by electing Francis to a position of supreme authority, only has itself to blame. But in fact there is a reason why all Americans, including the Trump administration, should feel uneasy about the nomination of Cardinal McElroy.

Washington is the nation’s most corrupt diocese, thanks in part to its former archbishop ex-cardinal Theodore McCarrick, a serial abuser of seminarians. After his retirement in 2006, Benedict XVI, having heard rumours about the bed-hopping ‘Uncle Ted’, ordered him to keep a low profile.

McCarrick was spectacularly rehabilitated by Francis, who sent him around the world as his unofficial emissary. During these years he helped negotiate the Vatican’s notorious pact with Beijing; only when he was charged with child abuse did the Pope laicise him. Now, aged 94, McCarrick is too senile to stand trial. Many bishops and two popes were warned about McCarrick, though the Vatican has kept all the most sensitive details secret. What we do know, however, is that in 2016 America’s foremost authority on clerical sex abuse, the late Richard Sipe, wrote to Bishop Robert McElroy of San Diego, with whom he had previously discussed the matter, telling him that ‘I have interviewed 12 seminarians and priests who attest to propositions, harassment or sex with McCarrick.’

The Pillar alleged that: ‘After he received that letter, McElroy declined to meet with Sipe again. Even when Sipe hired a process server to hand-deliver a letter, McElroy turned down a meeting – saying later that Sipe’s apparently desperate behaviour indicated he was untrustworthy.’

McElroy later said that Sipe’s ‘information’ was passed on to Rome, but we still do not know whether that information consisted of the letter, or who was responsible for sending it on. At any rate, there was no ‘radical inclusion’ for Uncle Ted’s victims until the Vatican was forced to remove him from public ministry in 2018.

Cardinal McElroy’s responsibility for this state of affairs is impossible to assess because he has said so little. And that, rather than any point-scoring between Francis and Trump, is why his appointment to Washington is a disgrace.

Damian unpacks what the Trump administration could mean for religious freedoms in America with Andrea Picciotti-Bayer, director of the US-based Conscience Project, and The Spectator’s deputy editor Freddy Gray on the latest Holy Smoke podcast:

Immigration’s theatre of the absurd

On the cusp of an almighty row over Trump’s planned mass deportations, let’s look to Europe for light relief.

Last month, the pridefully left-wing management of the storied 19th-century Parisian theatre Gaité Lyrique, owned by the pridefully left-wing Paris council and traditionally the home of operettas, digital arts and musical performances, staged a free conference on ‘reinventing the refugee welcome in France’. The organisers literally invited their own downfall: 200 West African migrants who apparently felt very welcome indeed and refused to leave.

Gaité Lyrique invited its own downfall: 200 West African migrants who refused to leave

These passionate opera fans have since swelled to 350. The pridefully left-wing management cannot, of course, bring themselves to eject their newly permanent audience, who we presume are hoping to subscribe for a full season. Meanwhile, activists have seized on the ‘anti-racist, anti-colonial’ cause célèbre, shuttling boxes of fruit and vegetables into the venue, though no theatre is set up to function as a soup kitchen. The building’s zero showers and lone pair of toilets dizzy the imagination. When the story was reported, British comments exploded with bitter hilarity: ‘For goodness sake. The theatre is far too small. Bus them all to Versailles and they can invite their friends.’

Although another commenter noted that for Gaité Lyrique this is probably ‘the best show they’ve put on in years’, the spectacle isn’t, alas, proving profitable. All other events have been cancelled. Gaité Lyrique depends on ticket sales and cannot afford to sponsor a ceaseless piece of improvisational performance art that’s free to the public. The pridefully left-wing theatre is not only suffering physical degradation I’m reluctant to picture too vividly, but is struggling to pay 60-some employees. It’s going bankrupt.

Obviously, this fiasco is a metaphor for European immigration more generally. Either by inviting bums on seats or being lax about checking tickets at the door, our pridefully left-wing governments and civil servants have allowed in a rabble of poorly educated visitors from the ‘developing world’ – at a certain point, you have to ask, developing into what? – who aren’t leaving. The presence of these sizeable contingents amounts to blackmail. The migrants sleeping on tables in Gaité Lyrique are holding out for free accommodation, which, until it’s on offer, they will simply seize. In kind, because people take up physical, economic and political space, illegal immigration is an annexation of someone else’s territory.

If seemingly presumptuous, the occupiers in Paris illustrate an emotional progression altogether human and therefore predictable. Humble supplicants at sea in a strange land don’t remain supplicants for long. Beseeching accelerates to demand. Whatever you give people, they soon take for granted and believe they deserve. Benefits thus become entitlements, and entitlements are always insufficient. Foreigners from hard-scrabble countries rapidly adapt to a culture in which it’s reasonable to expect a warm, safe place to live, a full fridge and a car. Inexorably, then, the initial gratitude of destitute immigrants can slide to resentment.

Besides, gormless, vainglorious progressive altruism is an open invitation to being taken advantage of. The folks staging their ‘refugee welcome’ would have anticipated gushing thanks from their West African beneficiaries for generously ‘inclusive’ speeches from the likes of the Red Cross. But these Africans didn’t want speeches. They wanted housing. Want your theatre back? Gimme an apartment.

Desperation being a keen pedagogical motivator, most migrants are quick studies. They learn our immigration loopholes – such as the obligation of the French state to provide free digs to migrants who are unaccompanied minors. Accordingly, the theatre’s occupiers chant from its steps: ‘Shame on this power who declares war on unaccompanied minors!’ Although both French authorities and local observers estimate that nearly all these men are at least in their twenties, everyone quoted in the press claims to be 16. If migrants take us for mugs, that’s because we are mugs.

Canny migrants also learn to use a host country’s own propaganda and political vanities as weapons. Gaité Lyrique’s occupiers shout through megaphones ‘We’re all equal, not illegal!’ and ‘We want liberty, equality, fraternity!’ In the UK, migrants latch on to lingo about free speech and human rights. America’s preening about being a ‘nation of immigrants’ can easily be deployed to argue that it’s hypocritical to keep anyone out. Throughout the West, officialdom’s sensitivity to discrimination against sexual minorities and sympathy for the perils faced by any Muslim who converts to Christianity leave immigration judges open to being suckered.

Lastly, do-gooders always expect other people to pay the price of their goodness. That may be what makes this story so rich. With considerable success in both the US and UK, droves of righteous charity workers are helping foreigners enter illegally and avoid deportation. In other words, progressives are continually giving our countries away, when our countries aren’t theirs to give. At least in Paris the do-gooders themselves are sacrificing for their largesse on our behalf. The money the theatre is losing should pay its lofty staff’s salaries. For once the open-borders crowd has incited trespassing that encroaches on their own space, and arty immigration advocates have invited freeloading that costs them personally. Far more commonly, publicly financed NGOs that champion migration dump the costs of newcomers’ hotels and shelters, healthcare and education on the host nation’s taxpayers.

The occupation in Paris is loud and raucous. Dope hazes the block, fights often break out and the park across the street has long since been abandoned by local French families. Thus nearby eateries are suffering from a precipitous loss of custom, which the restaurateurs do not deserve. Nevertheless, it’s satisfying to see immigration worthies hoisted on the petard of their own gullibility. British newspaper readers would find this story even more satisfying were they not justifiably convinced that the abundance of the theatre’s occupiers will in short order rock up on the coast of Kent – at which point the Home Office will clasp these ‘vulnerable’, unparented wayfarers to the bosom of the United Kingdom. After all, they’re only 16.

London Classic

My first round game from the first edition of the London Chess Classic in 2009 remains a vivid memory, not least because it ran for 163 moves and nearly eight hours. (I won!) England’s premier international event returned for its 14th edition in December, having skipped two pandemic years, with new sponsorship from XTX markets, and a new venue at the Emirates Stadium in London. The programme included a dozen separate events, headed by an elite invitational tournament in which the top seeds were the former world championship candidates Shakhriyar Mamedyarov and Vidit Gujrathi. They tied for second place in the final tables, alongside the England team members Michael Adams and Nikita Vitiugov.

The winner, a point ahead of all of them, was Gawain Jones, who completed a magnificent treble, having also won the English Championship in June and the British Championship in August. Winning the London Chess Classic is a career-best tournament victory for Gawain Jones, and all the more remarkable for the adversity in which it was achieved. In 2023, his wife, Sue Maroroa Jones, died from sepsis at the age of 32, just a week after giving birth to their second child.

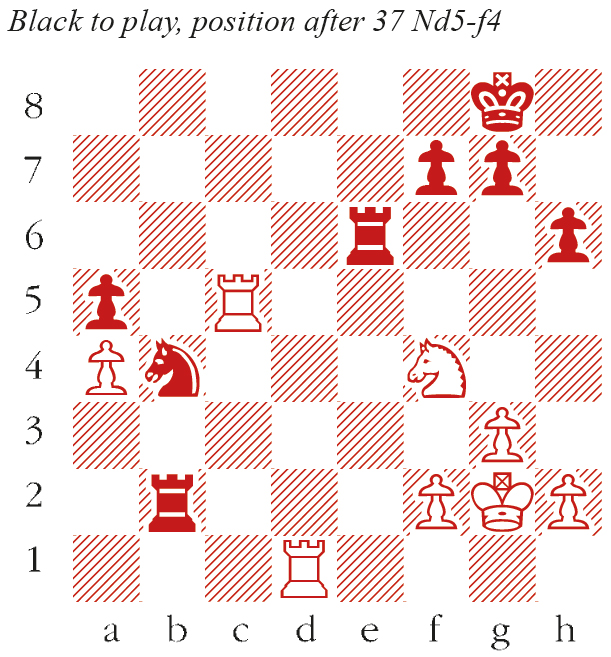

The position in the first diagram is taken from his win against Adams in the first round. Jones has just played 37 Nd5-f4, hitting the rook on e6. Adams was running short of time, having worked to neutralise Jones’s slight initiative for most of the game. His decision here looks plausible, moving the attacked rook and defending the pawn, but it cost him the game.

Gawain Jones–Michael Adams

London Chess Classic, Emirates Stadium, 2024

37… Ra6? Seeking counterplay with 37…Rc6! would have secured a draw. After 38 Rxa5 Rcc2 39 Rf1 g5, Black’s active pieces are active enough that the extra pawn won’t tell. 38 Rc8+ Kh7 39 Rd7! Most likely, Adams had counted on 39 Rdd8 g6, when 40 Rh8+ Kg7 41 Rdg8+ Kf6 42 Rxh6 Rd6! prepares Rd6-d2. Poking the f7-pawn first is far more effective, for example after 39…f6 40 Rdd8 g5 41 Rd7 is mate. Rc6 40 Rf8 Rf6 In comparison with the variation above, the black king’s escape is sealed off.

41 Rdd8 Black resigns He finished the tournament with some neat technique against the women’s world champion from China.

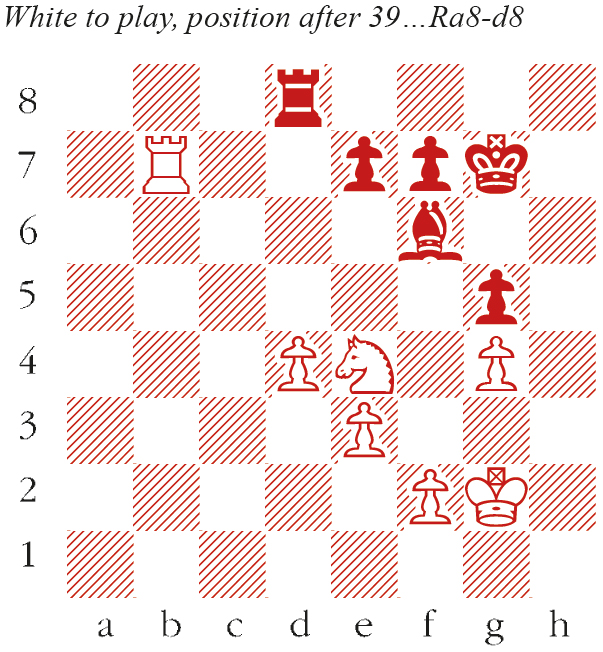

Gawain Jones–Ju Wenjun

London Chess Classic, Emirates Stadium, 2024

40 Rb5! Instead 40 f4? gxf4 41 g5 would be too hasty. After 41…Bxd4 42 exd4 Rxd4 43 Rxe7 Rd3 White probably cannot win. Kg6 41 Rf5! Now the winning plan is straightforward: d4-d5-d6, followed by Nxf6 exf6 and Rf5-d5 to support the pawn. White will win easily by advancing the king to e4 and waiting for Black to run out of moves. So Black resigns

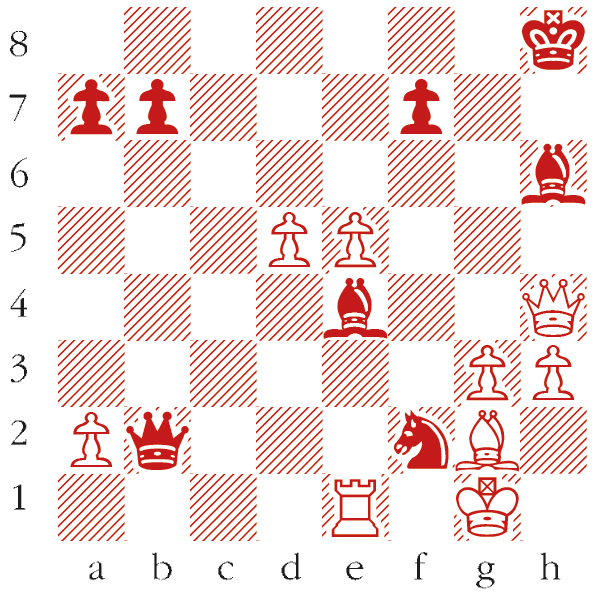

No. 834

Black to play. Gukesh-Giri, Wijk aan Zee, 2025. With less than a minute, Giri erred and lost here. Which move would have won him the game? Email answers to chess@spectator.co.uk by Monday 27 January. There is a prize of a £20 John Lewis voucher for the first correct answer out of a hat. Please include a postal address.

Last week’s solution 1 Qxd5! exd5 2 Re8+ Bf8 3 Rxf8+ Kxf8 (or 3…Kg7 4 Rxf7+ Qxf7 5 Nxf7 Kxf7 6 hxg6+) 4 Nh7+ Kg7 5 Nxf6 Kxf6 6 h6! wins

Last week’s winner Stephen Belding, Rugby, Warwickshire

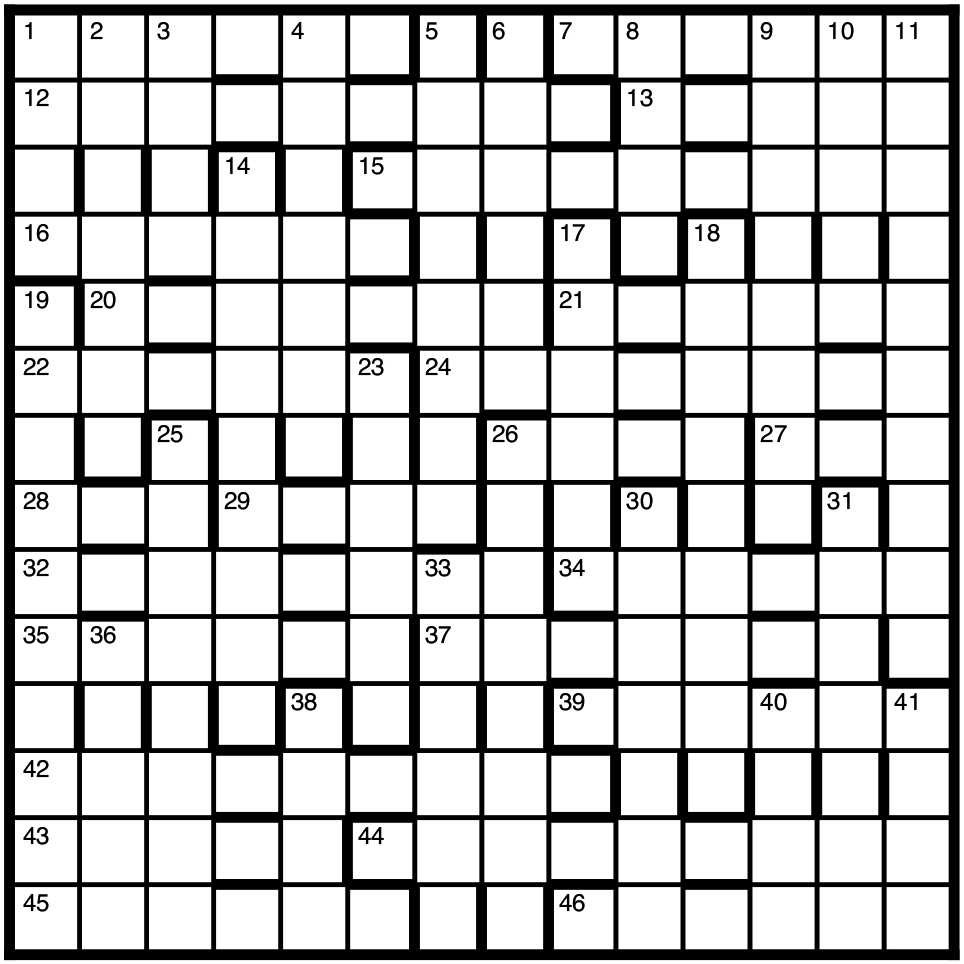

Spectator Competition: Out of this world

In Competition 3383 you were invited to submit a Tripadvisor-type review by an alien who has visited Earth for the first time. Frank Upton pointed out that it could have been titled ‘Mostly Harmless’, Ford Prefect’s entire entry for Earth in The Hitch-hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. The submissions were full of inventive detail and hard to whittle down. I liked Bill Greenwell’s prankster alien: ‘Staid the nihgt on Manhattan, enjoyd the screeming, skyscapers were a pushover.’ Jonathan White’s extraterrestrial dug jazz (‘an audible chaos I could resonate with’) while Mark Ambrose’s was amused by Earthlings believing Stonehenge to be manmade: ‘Some of the ancient stones from Kalibor’s moon have fallen down, but you can still make out the first landing site.’ Chris O’Carroll’s visitor was pithy about humanity’s prospects: ‘We wish them well.’ The £25 John Lewis vouchers go to the following.

From intergalactic space, Earth enticed; a warming blue-green bauble: so much for advertising. On arrival, we found two whole thirds of the place ocean, which was both unhealthily saline and monotonous to experience, while too much of the land proved beige. The so-called ‘sights’ were predominantly stretches of peculiarly convex or concave landscape, the remainder being pathetic architectural sallies on the part of the natives to compete with same. Abstract beauty at times distinguished the flora, though the best of it flourished in areas devoid of properly educative signage. The resident bipeds kept insisting upon taking us to their leaders – convinced the idea was ours – though we are apolitical and only wanted a drink and a sit down. We asked these leaders what there was to do on Earth, receiving a surprising number of invitations to participate in armed combat on their behalf. Asvacationers, we naturally demurred.

Adrian Fry

We booked our trip to Planet 3 with Star Trekkers. They’re a great company and we had a blast. The kids loved the activities, including using our ship’s thrusters to make fun shapes in agricultural plantations and the ‘how-slow-can-you-go’ challenge, where they took the controls to try and fly alongside one of the ancient winged machines used by the aboriginals. Qzzsk got bored and zoomed us 12 miles up into space in three seconds, to general hilarity. The highlight was the hands-on wildlife experience: we beamed up an aboriginal and examined it. Yours truly got to have a go with the probe – what fun! When we put the creature back where we had found it (more or less) our guide told it: ‘Take me to your leader,’ which had us in stitches. Planet 3, of course, does not have what we recognise as leaders.

Joseph Houlihan

You don’t go to Earth (what a dull name – wake up, Tourism Earth!) for the atmosphere. That’s thin and full of nitrogen, which made us put on weight (don’t forget your H2S tablets). The fascinating thing about this Class M planet is the way it is divided up into ‘countries’, with ‘governments’, since the Earthians seem incapable of organising anything without a hierarchy telling them what to do. We preferred the authoritarian countries as being authentically ‘Earthy’ – think sandroller nest back home – and if you’ve only got time for one, choose China. Every kind of scenery; food like home if you know where to look; things work; and you can get away from the huge expanses of sodium chloride solution that waste so much space on this planet. Do watch out for one thing, though – we smell as funny to Earthians as they do to us! But enjoy!

Frank Upton

One thing that can safely be said about Earth is that it is a planet of contrasts. Even its population requires two differential human anatomies with interlocking organs to reproduce itself. This is called ‘mating’, and an immense portion of mental, social and cultural life on Earth is concerned with it. Don’t be put off – it is their way, and a very popular one. The danger of overpopulation is averted by mortal antagonisms. This is another proof that Earth’s core dynamic is a systematic balance of opposites. So the general ‘vibe’, as a native might say, is volatile. The UK, an island nation, was chosen as a case study. Our researchers found that its instability was off the scale, but the range of archaic ruins, picturesque fire-damaged buildings, abandoned transport projects and miraculous sewage overflows that can be visited has to be seen to be believed.

Basil Ransome-Davies

1 Star: Nice scenery, shame about the bipeds.